A Mesozoic clown beetle myrmecophile (Coleoptera: Histeridae)

Figures

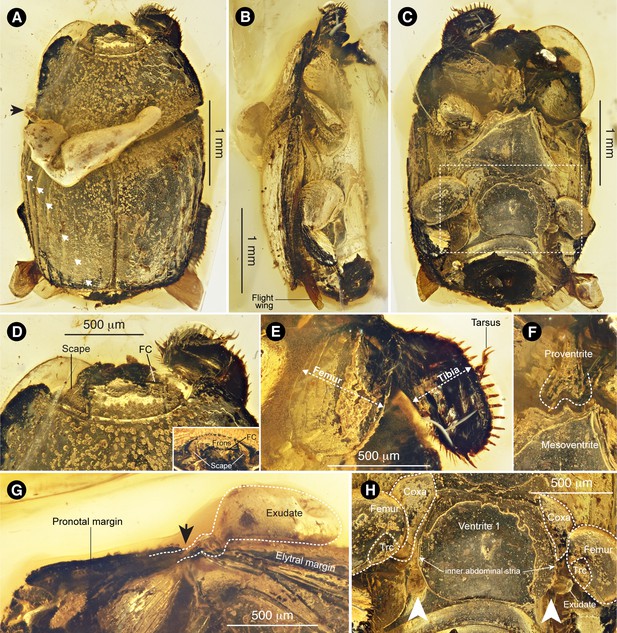

Promyrmister kistneri gen.et sp. nov.

(A) Dorsal habitus of holotype CNU-008021 with origin of exudate globule (black arrow) and elytral striae (white arrows) indicated; the three lateral striae are complete (top three arrows), the three medial striae appear incomplete. (B) Right lateral habitus with flight wing indicated. (C) Ventral habitus, boxed region expanded in panel H. (D) Head, dorsal and (inset) frontal views, with antennal scapes and frontoclypeal carina (FC) indicated. (E) Right foreleg, laterally expanded femur and tibia indicated. (F) Proventral-mesoventral boundary showing proventral keel with posterior incision. (G) Left pronotal margin, lateral view, showing possible origin of putative glandular exudate; arrow in G corresponds to that in panel A. (H) Ventrite one showing proximal leg segments (Trc: trochanter) and postcoxal gland openings (white arrows), with globule of putative exudate emanating from left postcoxal gland opening.

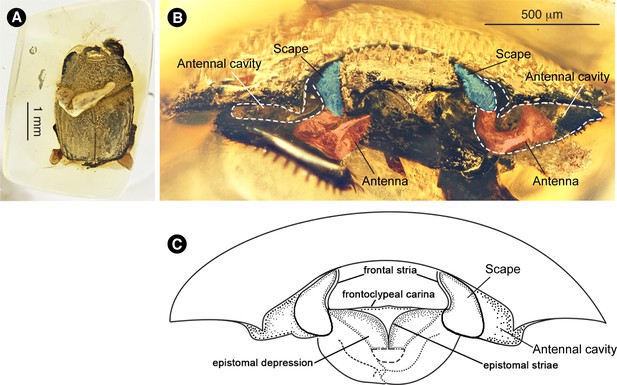

Amber piece and frontal view of holotype of Promyrmister kistneri sp.nov.

(CNU-008021). (A) Amber piece containing holotype. (B) Frontal view of head. Scapes (covering eyes) shaded blue, apex of antenna red. Lateral concavities to receive antennae demarcated by white dotted lines. (C) Diagram of frontal view of head, to show key systematic characters.

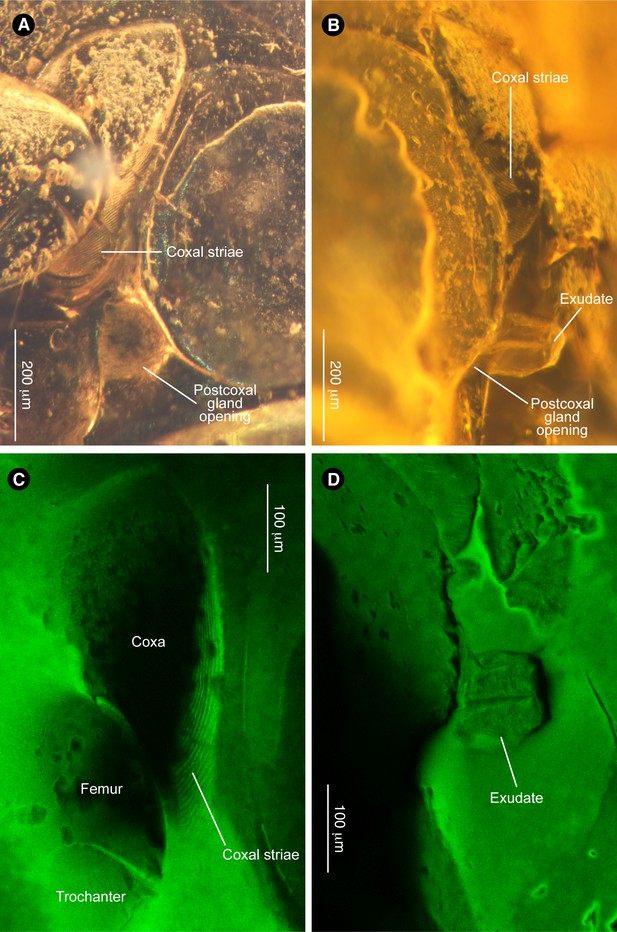

Further morphology of Promyrmister.

(A) Right coxal region showing postcoxal glandular opening and coxal striae. (B) Left coxal region showing postcoxal glandular opening with exudate. (C) Confocal image of right metacoxa showing oblique striae on inner side. (D) Confocal image of left gland opening secreting exudate.

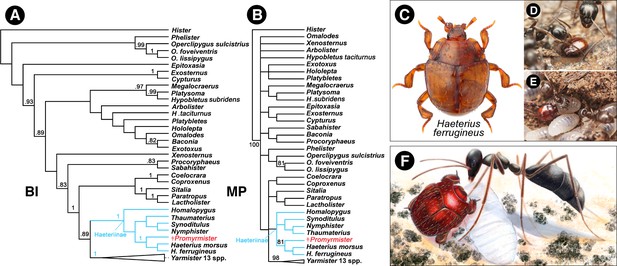

Phylogenetic relationships of Promyrmister.

(A) Consensus Bayesian Inference (BI) tree of representative histerid taxa including Haeteriinae, and Promyrmister. Posterior probabilities above 0.8 are shown on branches. (B) The consensus parsimony tree (MP) using TNT under the Traditional Search; bootstrap percentages above 80 are shown on branches. (C) Habitus photograph of Haeterius (H. ferrugineus), an inferred extant close relative of Promyrmister (photo credit: C. Fägerström) (D, E) Living Haeterius ferrugineus beetles interacting with Formica (D) and Lasius (E) host ants (photo credit: P. Krásenský). (F) Reconstruction of Promyrmister with stem-group host ant and larva (ant based on Gerontoformica).

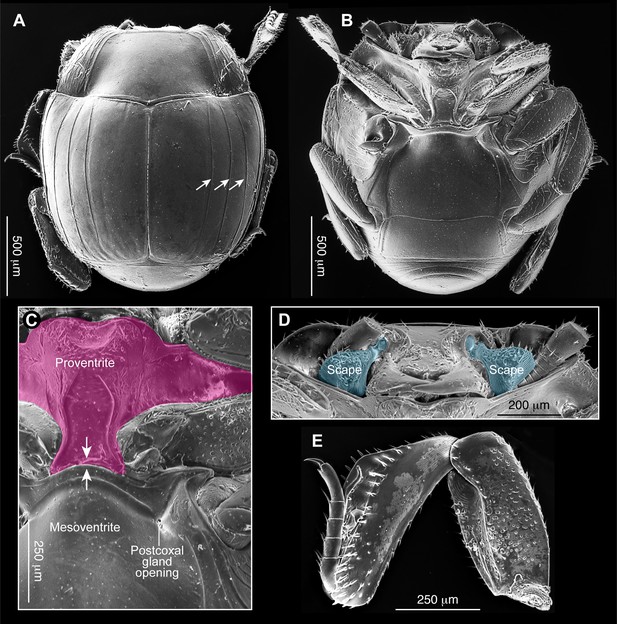

Scanning electron micrographs of extant Haeterius ferrugineus (Olivier, 1789).

(A) Habitus in dorsal view with three elytral striae indicated by arrows; (B) Habitus in ventral view; (C) Ventral thoracic region with proventrite colored pink to show expanded proventral lobe (anterior margin) covering underside of head, and proventral keel (posterior margin) which receives the mesoventral process. Left postcoxal glandular opening is indicated. (D) Ventral head showing retraction under pronotum and flattened clypeus aligned along dorsoventral plane of the body. Enlarged scapes (blue) cover eyes, and antennae retract into prothoracic cavities. (E) Middle leg showing expanded femur and tibia.

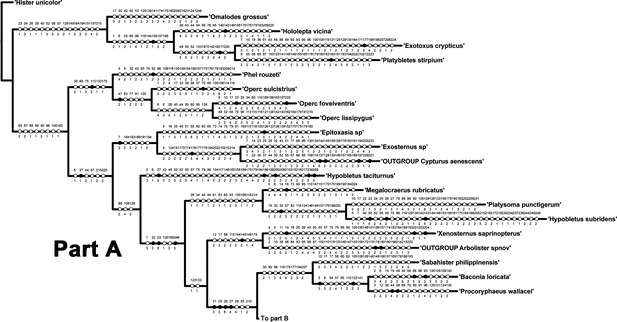

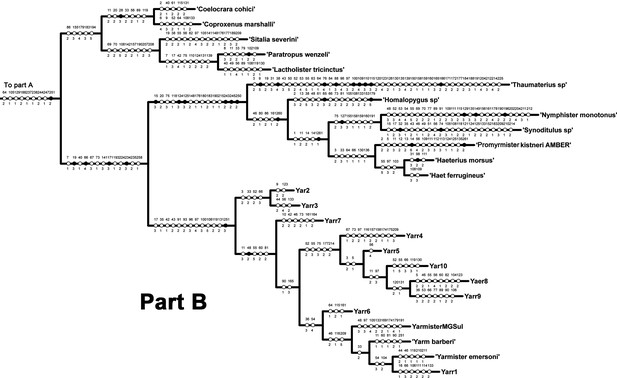

Part A of single tree obtained by parsimony analysis of morphological matrix using implied weighting (K = 13) in TNT.

Character mapping in WinClada with unambiguous optimization. Black circles indicate unique character state changes; white circles indicate parallelisms or reversals; character numbers are above circles; character states are below circles.

Part B of single tree obtained by parsimony analysis of morphological matrix using implied weighting (K = 13) in TNT.

Character mapping in WinClada with unambiguous optimization. Black circles indicate unique character state changes; white circles indicate parallelisms or reversals; character numbers are above circles; character states are below circles.

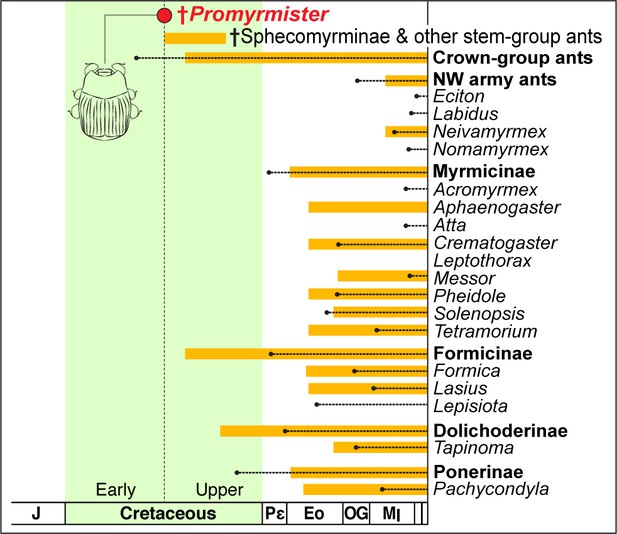

Antiquity of Promymister implies pervasive host switching of Haeteriinae from Cretaceous to Recent.

Age of Promyrmister is shown (red circle). The inferred window of occurrence of stem-group ants is indicated by the top orange bar. The ages of crown-group ants as a whole, New World (NW) army ants, and other specific subfamilies and genera that are known hosts of Haeteriinae are also presented. Orange bars extend back from the Recent to the age of the earliest-known fossil; dotted lines extend back to molecularly-inferred origins of crown groups. Molecular dating implies crown-group ants existed at the same time as Promyrmister, but stem-group ants are the only ants so far known in Burmese and other contemporaneous ambers. All modern host ant genera are inferred to have Cenozoic origins, implying extensive host switching between the inferred Early Cretaceous origin of Haeteriinae and the present day.

Diversity of modern Haeteriinae associated with Neotropical army ants (Ecitonini).

(A) Colonides beetle walks in an emigration of Eciton burchellii army ants. Note the color mimicry of the host ant (Peru; photo: Taku Shimada). (B) Euxenister beetle walking alongside an Eciton hamatum army ant worker. The long legs facilitate grooming ants to obtain the colony odor, as well as clinging to emigrating workers (Peru; photo credit: Takashi Komatsu). (C) Nymphister kronaueri beetle phoretically attached to the petiole of an Eciton mexicanum army ant worker. The beetles bite onto this part of the ant’s body, enabling them to migrate with the host. The beetle resembles the ant’s gaster from above, potentially camouflaging the beetles to avoid predation (Costa Rica; photo credit: Daniel Kronauer).

Additional files

-

Supplementary file 1

Complete matrix of 46 taxa, 261 characters constructed in Mesquite v. 3.20.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.44985.012

-

Supplementary file 2

Histerid taxa sampled for phylogenetic analysis, and ages of haeteriine host ant genera inferred from fossil and molecular data.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.44985.013

-

Transparent reporting form

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.44985.014