The paraventricular thalamus is a critical mediator of top-down control of cue-motivated behavior in rats

Figures

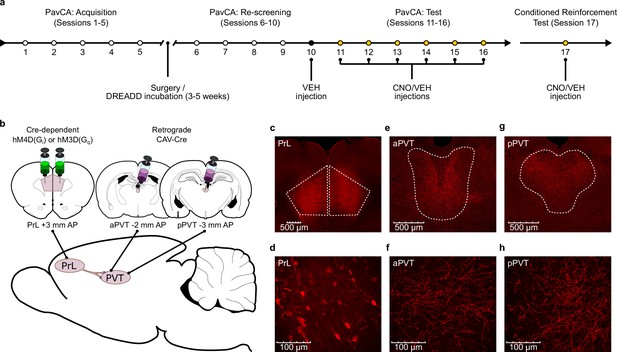

Experiment 1 methods.

(a) Timeline of the experimental procedures. Rats were trained in a Pavlovian Conditioned Approach (PavCA) paradigm for five consecutive days (Acquisition, Sessions 1–5) and phenotyped as sign- (STs) or goal-trackers (GTs). Following acquisition, STs and GTs underwent DREADD surgeries for delivering Gi- or Gq- DREADDs in neurons of the prelimbic cortex (PrL) projecting to the paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT). Incubation time for DREADD expression was 3–5 weeks. After incubation, rats were re-screened for sign- and goal-tracking behavior (Re-screening, Sessions 6–10). All rats received an i.p. VEH injection 25 min before session 10 to habituate them to the injection procedure. CNO (3 mg/kg) or VEH were then administered i.p. every day during the Test phase (Sessions 11–16), 25 min before the start of each session. 24 hr after the last session of PavCA, rats received an additional injection of CNO or VEH 25 min before being exposed to a Conditioned Teinforcement Test (CRT, Session 17). (b) Schematic of the dual-vector strategy used for expressing Gi- or Gq- DREADDs in the PrL-PVT pathway. (c,d) Photomicrographs representing mCherry expression in pyramidal neurons of the PrL projecting to the PVT at (c) 4x magnification and (d) 40x magnification. (e,f) Photomicrographs of mCherry expression representing terminal fibers in the anterior PVT coming from the PrL at (e) 10x magnification and at (f) 40x magnification. (g,h) Photomicrographs of mCherry expression representing terminal fibers in the posterior PVT coming from the PrL at (g) 10x magnification and (h) 40x magnification.

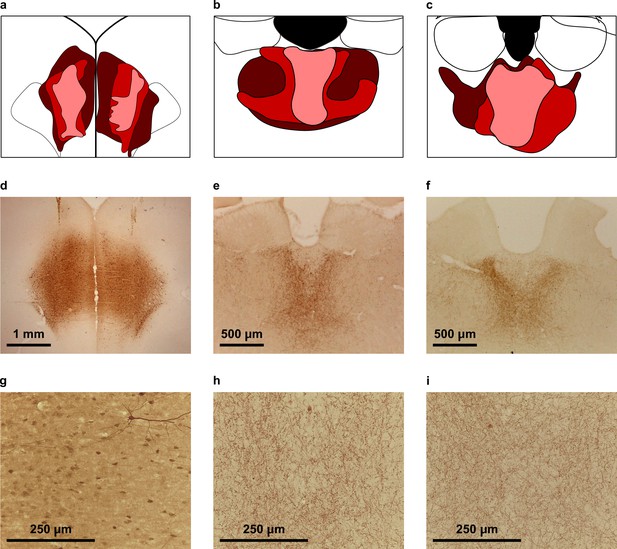

Representative photomicrographs of mCherry expression.

(a,b,c) Schematic representation of the viral spread in the (a) PrL, (b) aPVT and (c) pPVT. Subjects included in the final analyses were assigned a score of 1–3 according to both the intensity and spread of DREADD expression in the areas of interest. Subjects with the least expression (represented by the pink areas) were assigned a score of 1, subjects with medium expression (represented by the red areas) were assigned a score of 2, and subjects with the most expression (represented by the maroon areas) were assigned a score of 3. (d,g) Photomicrographs representing mCherry expression in the pyramidal neurons of the PrL projecting to the PVT at (d) 2.5x magnification and (g) 20x magnification. (e,h) Photomicrographs of mCherry expression representing terminal fibers in the aPVT coming from the PrL at (e) 5x magnification and at (h) 20x magnification. (f,i) Photomicrographs of mCherry expression representing terminal fibers in the aPVT coming from the PrL at (f) 5x magnification and (i) 20x magnification.

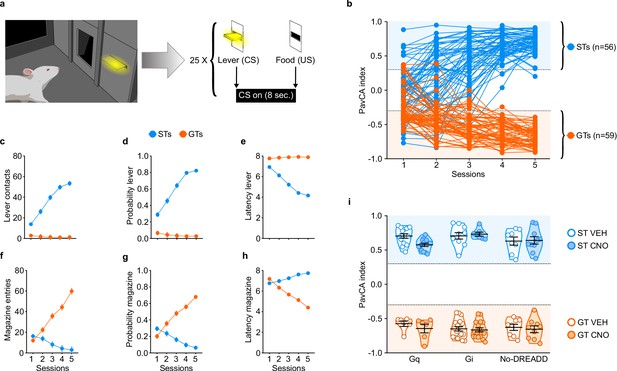

Acquisition of sign- and goal-tracking behaviors during 5 sessions of Pavlovian Conditioned Approach (PavCA) training (i.e. prior to surgery or CNO administration).

(a) Schematic representing the PavCA task. Rats were presented with an illuminated lever (conditioned stimulus, CS) for 8 s followed by the delivery of a food pellet (unconditioned stimulus, US) immediately upon lever-CS retraction. Each PavCA session consisted of 25 lever-food pairings. (b) PavCA index scores (composite index of Pavlovian conditioned approach behavior) for individual rats across 5 sessions of Pavlovian conditioning. PavCA index from session 4–5 were averaged to determine the behavioral phenotype. Rats with a PavCA score <−0.3 were classified as goal-trackers (GTs, n = 59), rats with a PavCA score >+0.3 were classified as sign-trackers (STs, n = 56). (c–e) Acquisition of lever-directed behaviors (sign-tracking) during PavCA training. Mean ± SEM for (c) number of lever contacts, (d) probability to contact the lever, and (e) latency to contact the lever. (f–h) Acquisition of magazine-directed behaviors (goal-tracking) during PavCA training. Mean ± SEM for (f) number of magazine entries, (g) probability to enter the magazine, and (h) latency to enter the magazine. (i) Data are expressed as individual data points with mean ± SEM plotted on violin plots for PavCA index. Rats with similar PavCA scores were assigned to receive different G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR; Gi, Gq or no-DREADD) and different treatment (CNO, VEH). Baseline differences in PavCA index between experimental groups were assessed by using a 3-way ANOVA with phenotype (GT, ST), GPCR (Gi, Gq and no-DREADD) and treatment (CNO, VEH) as independent variables and PavCA index as the dependent variable. A significant effect of phenotype was found (p<0.001), but no significant differences between experimental groups and no significant interactions. Sample sizes: GT-Gi = 32, GT-Gq = 12, ST-Gi = 14, ST-Gq = 25, GT-no DREADD = 15, ST-no DREADD = 17.

-

Figure 2—source data 1

Acquisition of lever- and magazine-directed behaviors during 5 sessions of PavCA training (Figure 2c–h).

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.005

-

Figure 2—source data 2

Average PavCA index scores during session 4–5 of PavCA training (Figure 2b,i).

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.006

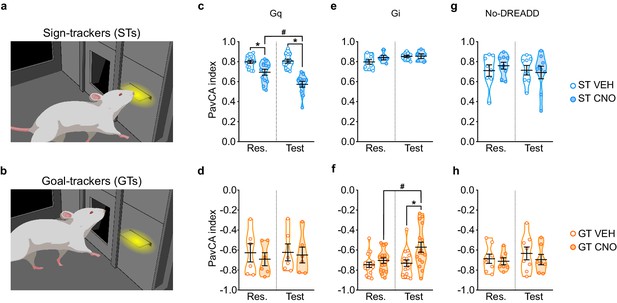

Chemogenetic stimulation of the PrL-PVT pathway decreases sign-tracking behavior in sign-trackers, while chemogenetic inhibition of the PrL-PVT pathway increases sign-tracking behavior in goal-trackers.

(a,b) Drawing representative of sign-tracking (a) and goal-tracking (b) conditioned responses during PavCA training. (c–h) Data are expressed as individual data points with mean ± SEM plotted on violin plots for PavCA index during Rescreening (Res., average of PCA Sessions 6–10) and Test (average of PCA Sessions 11–16) periods. (c,d) Chemogenetic stimulation (Gq) of the PrL-PVT circuit decreases the PavCA index in (c) sign-trackers, but has no effect in (d) goal-trackers. There was a significant treatment x session interaction in sign-trackers (p<0.01). Pairwise comparisons showed that CNO decreased the PavCA index in STs (*p<0.001, CNO vs. VEH; #p<0.001, Test vs. Res.). (e,f) Chemogenetic inhibition of the PrL-PVT circuit has no effect on (e) sign-trackers, but increases the PavCA index in (f) goal-trackers. There was a significant treatment x session interaction in goal-trackers (*p<0.012 CNO vs. VEH; #p<0.002 Test vs. Res.). (g,h) Effects of CNO administration on the PavCA index in non-DREADD expressing (g) STs and GTs (h). When DREADD receptors were not expressed in the brain, CNO had no effect on the PavCA index in either sign-trackers nor goal-trackers. Sample sizes: GT-Gi = 32, GT-Gq = 12, ST-Gi = 14, ST-Gq = 25, GT-no DREADD = 15, ST-no DREADD = 17.

-

Figure 3—source data 1

Behavioral data during the rescreening and test sessions for ST-Gq (Figure 3c).

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.010

-

Figure 3—source data 2

Behavioral data during the rescreening and test sessions for GT-Gq (Figure 3d).

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.011

-

Figure 3—source data 3

Behavioral data during the rescreening and test sessions for ST-Gi (Figure 3e).

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.012

-

Figure 3—source data 4

Behavioral data during the rescreening and test sessions for GT-Gi (Figure 3f).

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.013

-

Figure 3—source data 5

Behavioral data during the rescreening and test sessions for ST-No DREADD controls (Figure 3g).

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.014

-

Figure 3—source data 6

Behavioral data during the rescreening and test sessions for GT-No DREADD controls (Figure 3h).

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.015

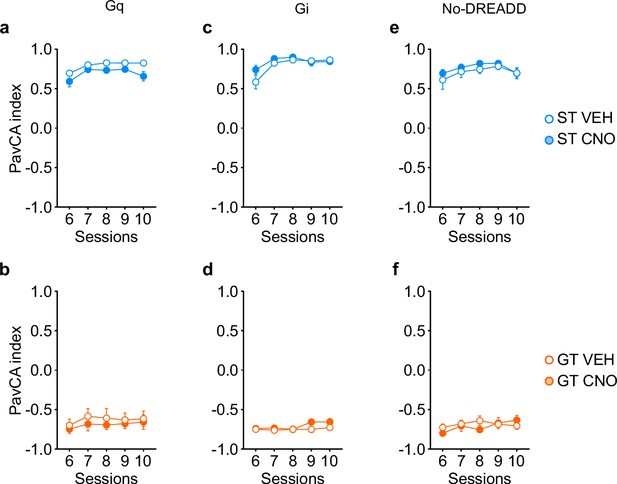

Analysis of Pavlovian conditioned approach behaviors during the rescreening phase of the study (PavCA sessions 6–10, prior to treatment).

(a–f) Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of the Pavlovian conditioned Approach (PavCA) index during Rescreening Sessions 6–10 for STs expressing (a) Gq, (c) Gi or (e) No-DREADD in the PrL-PVT pathway. A linear mixed-model analysis revealed a significant effect of session for ST-Gq (F4,71.508 = 5.400, p<0.001), ST-Gi (F4,25,678 = 4.990, p = 0.004), and ST-No DREADD (F4,15 = 3.734, p = 0.027), indicating that subjects from all groups increased their PavCA index across the five rescreening sessions. For ST-Gq there was also a significant effect of treatment (F1,22.900 = 7.893, p = 0.010), indicating that subjects from the CNO group had a lower PavCA index compared to subjects from the VEH group. There was not a significant treatment x session interaction. (b,d,f) Data are shown for GTs expressing (b) Gq, (d) Gi or (f) No-DREADD in the PrL-PVT pathway. A linear mixed-model analysis revealed no significant effect of session, treatment, nor a significant treatment x session interaction in any of the GT experimental groups.

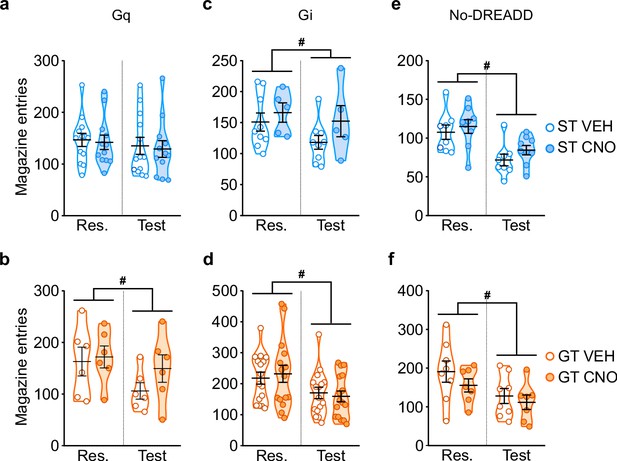

Analysis of magazine entries during the intertrial interval (ITI).

(a–f) Data are expressed as individual data points with mean ± SEM plotted on violin plots for magazine entries during the intertrial interval (ITI) during Rescreening (Res., average of PCA Sessions 6–10) and Test (average of PCA Sessions 11–16). (a,b) Stimulation of the PrL-PVT pathway does not affect behavior during the intertrial interval of Pavlovian conditioning. For (a) STs, no significant effect of treatment, session, nor treatment x session interactions were found. For (b) GTs, there was no significant effect of treatment, nor a significant treatment x session interaction. There was, however, a significant effect of session (F1,10 = 11.556, p = 0.007) for GTs, suggesting that magazine entries during the ITI decrease across training, independent of treatment. (c,d) Inhibition of the PrL-PVT pathway does not affect behavior during the intertrial interval for rats in the Gi-DREADD group. There was not a significant effect of treatment, nor was there a significant treatment x session interaction for either (c) STs or (d) GTs. There was a significant effect of session for both phenotypes (STs: F1,12 = 5.692, p = 0.034; GTs: F1,30 = 42.243, p<0.001). As above, these data indicate that magazine entries during the ITI decrease with training, but independent of treatment. (e,f) CNO administration in the absence of DREADD receptors does not affect behavior during the intertrial interval of Pavlovian conditioning. There was not a significant effect of treatment, nor a significant treatment x session interaction for either (e) STs or (f) GTs. Consistent with the data from the Gi-DREADD group, there was a significant effect of session for both STs (F1,15 = 41.422, p<0.001) and GTs (F1,13 = 16.420, p = 0.001).

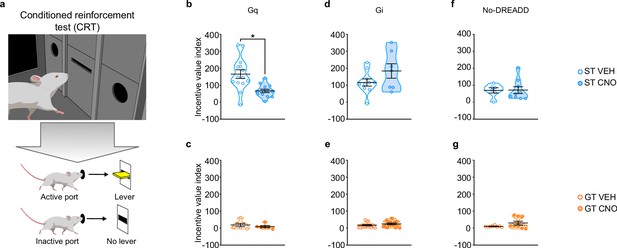

Chemogenetic stimulation of the PrL-PVT pathway decreases the conditioned reinforcing properties of a reward-paired cue in sign-trackers.

(a) Schematic representing the conditioned reinforcement test (CRT). Data are expressed as individual data points with mean ± SEM plotted on violin plots for Incentive value index ((active nosepokes + lever presses) – (inactive nosepokes)). (b,c) Relative to VEH controls, administration of CNO (3 mg/kp, i.p.) significantly decreased the incentive value of the reward cue for (b) ST-Gq (*p<0.05), but not (c) GT-Gq rats. (d,e) CNO-induced inhibition of the PrL-PVT circuit did not affect the conditioned reinforcing properties of the reward cue in (d) ST-Gi or (e) GT-Gi rats. (f,g) CNO administration did not affect the conditioned reinforcing properties of the reward cue in non-DREADD expressing (f) STs or (g) GTs. Sample sizes: GT-Gi = 32, GT-Gq = 12, ST-Gi = 14, ST-Gq = 25, GT-no DREADD = 15, ST-no DREADD = 17.

-

Figure 4—source data 1

Lever presses (Figure 4—figure supplement 1h), nosepokes (Figure 4—figure supplement 1a) and incentive value index (Figure 4b) during conditioned reinforcement for ST-Gq.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.018

-

Figure 4—source data 2

Lever presses (Figure 4—figure supplement 1h), nosepokes (Figure 4—figure supplement 1b) and incentive value index (Figure 4c) during conditioned reinforcement for GT-Gq.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.019

-

Figure 4—source data 3

Lever presses (Figure 4—figure supplement 1i), nosepokes (Figure 4—figure supplement 1c) and incentive value index (Figure 4d) during conditioned reinforcement for ST-Gi.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.020

-

Figure 4—source data 4

Lever presses (Figure 4—figure supplement 1j), nosepokes (Figure 4—figure supplement 1d) and incentive value index (Figure 4e) during conditioned reinforcement for GT-Gi.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.021

-

Figure 4—source data 5

Lever presses (Figure 4—figure supplement 1k), nosepokes (Figure 4—figure supplement 1e) and incentive value index (Figure 4f) during conditioned reinforcement for ST-No DREADD controls.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.022

-

Figure 4—source data 6

Lever presses (Figure 4—figure supplement 1l), nosepokes (Figure 4—figure supplement 1f) and incentive value index (Figure 4g) during conditioned reinforcement for GT-No DREADD controls.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.023

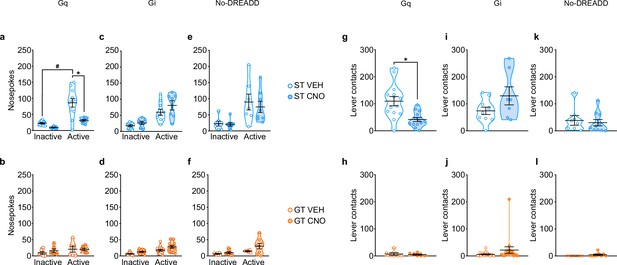

Chemogenetic stimulation of the PrL-PVT pathway decreases the conditioned reinforcing properties of a reward-paired cue in sign-trackers.

Data are expressed as individual data points with mean ± SEM plotted on violin plots. (a–f) Noespokes into the inactive (left) and active (right) ports during conditioned reinforcement. (a,b) Relative to VEH controls, administration of CNO (3 mg/kp, i.p.) significantly decreased active nosepokes for (a) ST-Gq rats (*p<0.05 vs. VEH; #p<0.05 vs. Inactive), but not (b) GT-Gq rats. (c,d) CNO-induced inhibition of the PrL-PVT circuit did not affect nosepokes in (c) ST-Gi or (d) GT-Gi rats. (e,f) CNO administration did not affect nosepokes in non-DREADD expressing (e) STs or (f) GTs. g–l) Lever contacts during conditioned reinforcement. (g,h) Relative to VEH controls, administration of CNO (3 mg/kp, i.p.) significantly decreased lever contacts for (g) ST-Gq rats (*p<0.05 vs. VEH), but not (h) GT-Gq rats. (i,j) CNO-induced inhibition of the PrL-PVT circuit did not affect lever contacts in (i) ST-Gi or (j) GT-Gi rats. (k,l) CNO administration did not affect lever contacts in non-DREADD expressing (k) STs or (l) GTs.

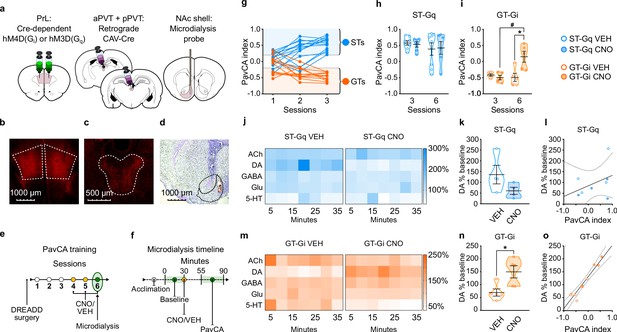

Experiment 2: Inhibition of the PrL-PVT circuit early in Pavlovian training elicits sign-tracking behavior and increases extracellular levels of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens shell (NAcS) of GT rats.

(a) Schematic of the cannulation surgery and the dual-vector strategy used for expressing Gi-DREADDs in the PrL-PVT pathway of GTs, or Gq-DREADDs in the PrL-PVT pathway of STs. (b–d) Representative pictures of coronal brain slices showing mCherry expression in the (b) PrL and (c) PVT, and the (d) placement of the microdialysis probe in the NAcS. (e) Experimental timeline. After surgery and DREADD incubation, rats were trained in a PavCA task for three consecutive Sessions (1-3) and classified as STs or GTs. Rats then received CNO (3 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle (VEH) 25 min before being trained for three additional PavCA Sessions (4-6). (f) Microdialysis timeline. Before the start of Session 6 of PavCA, microdialysis probes were inserted into the guide cannula and rats were left undisturbed for 2 hr before starting sample collection (acclimation period). After acclimation, six baseline dialysates were collected over 30 min before injecting rats with either CNO or vehicle (VEH). Session 6 of PavCA training started 25 min after CNO/VEH injections, and 7 fractions of dialysate were collected during the session. (g) lndividual PavCA index scores during the first 3 sessions of Pavlovian conditioning. Rats with a PavCA index <−0.2 were classified as GTs (n = 10), rats with a PavCA index >+0.2 were classified as STs (n = 13). (h,i) Data are expressed as mean ± SEM for PavCA index. (h) CNO during session 6 of training did not affect PavCA index in ST-Gq rats. (i) CNO during session 6 of training significantly increased the PavCA index in GT-Gi rats (*p=0.016 vs. VEH; #p=0.009 vs. session 3). (j,m) Heatmaps showing the relative percent (%) change from baseline of NAc shell acetylcholine (ACh), dopamine (DA), GABA, glutamate (Glu) and serotonin (5-HT) during Session 6 of PavCA training in (j) ST-Gq rats (blue) and (m) GT-Gi rats (orange). (k,n) Mean ± SEM levels of DA % change during Session 6 of Pavlovian conditioning in (k) ST-Gq and (n) GT-Gi rats. There was a significant effect of CNO for GT-Gi rats (*p=0.008). (l,o) correlations between DA % change from baseline and PavCA index during session 6 of PavCA training. No significant correlation was found in (l) ST-Gq. There was a significant positive correlation between percent change in DA and PavCA index in (o) GT-Gi rats (r2 = 0.92; p<0.001). Sample sizes: GT-Gi = 10; ST-Gq = 13 for behavior, nine for microdialysis data.

-

Figure 5—source data 1

PavCA index during session 1–3 of training (Figure 5g).

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.026

-

Figure 5—source data 2

PavCA index during session 3 vs session 6 of training for ST-Gq (Figure 5h).

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.027

-

Figure 5—source data 3

PavCA index during session 3 vs session 6 of training for GT-Gi (Figure 5i).

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.028

-

Figure 5—source data 4

Relative percent change from baseline of NAc shell acetylcholine (ACh), dopamine (DA), GABA, glutamate (Glu) and serotonin (5-HT) during Session 6 of PavCA training in ST-Gq (Figure 5j).

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.029

-

Figure 5—source data 5

Mean levels of NAc shell dopamine % change during Session 6 of PavCA training in ST-Gq (Figure 5k).

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.030

-

Figure 5—source data 6

Correlations between DA% change and PavCA index during session 6 of training in ST-Gq (Figure 5l).

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.031

-

Figure 5—source data 7

Relative percent change from baseline of NAc shell acetylcholine (ACh), dopamine (DA), GABA, glutamate (Glu) and serotonin (5-HT) during Session 6 of PavCA training in GT-Gi (Figure 5m).

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.032

-

Figure 5—source data 8

Mean levels of NAc shell dopamine % change during Session 6 of PavCA training in GT-Gi (Figure 5n).

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.033

-

Figure 5—source data 9

Correlations between DA% change and PavCA index during session 6 of training in GT-Gi (Figure 5o).

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.034

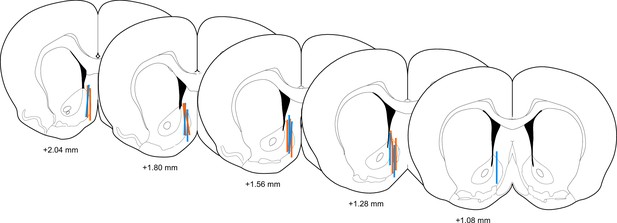

Microdialysis probe placement.

Representative drawing of coronal sections of the brain showing the placement of microdialysis probes in the nucleus accumbens shell. The bars indicate the area of active collection for STs (blue) and GTs (orange). Numbers indicate the approximate distance of the coronal slice relative to bregma.

Additional files

-

Supplementary file 1

Acquisition of Pavlovian conditioned approach during PavCA Sessions 1–5: lever-directed behaviors.

The results of linear mixed model analyses are shown for the effect of treatment (VEH vs. CNO) across sessions 1–5 of Pavlovian conditioned approach (PavCA) training for lever-directed behaviors, (lever contacts, probability to contact the lever and latency to contact the lever). Analyses were conducted separately for each experimental group (ST-Gq, GT-Gq, ST-Gi, GT-Gi, ST-no DREADD, GT-no DREADD). Bolded values indicate statistical significance, p<0.05.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.035

-

Supplementary file 2

Acquisition of Pavlovian conditioned approach during PavCA Sessions 1–5: magazine-directed behaviors.

The results of linear mixed model analyses are shown for the effect of treatment (VEH vs. CNO) across sessions 1–5 of Pavlovian conditioned approach (PavCA) training for magazine-directed behaviors (magazine entries, probability to enter the magazine, and latency to enter the magazine). Analyses were conducted separately for each experimental group (ST-Gq, GT-Gq, ST-Gi, GT-Gi, ST-no DREADD, GT-no DREADD). Bolded values indicate statistical significance, p<0.05.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.036

-

Supplementary file 3

PavCA rescreening (Sessions 6–10) vs. PavCA test (Sessions 11–16): lever-directed behaviors.

The results of linear mixed model analyses are shown for the effect of treatment (VEH vs. CNO), session (rescreening vs, test) and treatment x session interaction for lever-directed behaviors (lever contacts, probability to contact the lever and latency to contact the lever). Analyses were conducted separately for each experimental group (ST-Gq, GT-Gq, ST-Gi, GT-Gi, ST-no DREADD, GT-no DREADD). Bolded values indicate statistical significance, p<0.05.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.037

-

Supplementary file 4

PavCA rescreening (sessions 6–10) vs. PavCA test (sessions 11–16): magazine-directed behaviors.

The results of linear mixed model analyses are shown for the effect of treatment (VEH vs. CNO), session (rescreening vs, test) and treatment x session interaction for magazine-directed behaviors (magazine entries, probability to enter the magazine and latency to enter the magazine). Analyses were conducted separately for each experimental group (ST-Gq, GT-Gq, ST-Gi, GT-Gi, ST-no DREADD, GT-no DREADD). Bolded values indicate statistical significance, p<0.05.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.038

-

Supplementary file 5

Acquisition of sign-tracking behavior during PavCA Sessions 1–3: lever-directed behaviors.

The results of linear mixed model analyses are shown for the effect of treatment (VEH vs. CNO) across sessions 1–3 of Pavlovian conditioned approach (PavCA) training for lever-directed behaviors (lever contacts, probability to contact the lever and latency to contact the lever). Analyses were conducted separately for each experimental group (ST-Gq, GT-Gi). Bolded values indicate statistical significance, p<0.05.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.039

-

Supplementary file 6

Acquisition of sign-tracking behavior during PavCA Sessions 1–3: magazine-directed behaviors.

The results of linear mixed model analyses are shown for the effect of treatment (VEH vs. CNO) across sessions 1–3 of Pavlovian conditioned approach (PavCA) training for magazine-directed behaviors (magazine entries, probability to enter the magazine and latency to enter the magazine). Analyses were conducted separately for each experimental group (ST-Gq, GT-Gi). Bolded values indicate statistical significance, p<0.05.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.040

-

Supplementary file 7

Session 3 vs. Session 6 of PavCA training: lever-directed behaviors.

The results of linear mixed model analyses are shown for the effect of treatment (VEH vs. CNO), session (3 vs. 6) and treatment x session interaction for lever-directed behaviors (lever contacts, probability to contact the lever and latency to contact the lever). Analyses were conducted separately for each experimental group (ST-Gq, GT-Gi). Bolded values indicate statistical significance, p<0.05.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.041

-

Supplementary file 8

Session 3 vs. Session 6 of PavCA training: magazine-directed behaviors.

The results of linear mixed model analyses are shown for the effect of treatment (VEH vs. CNO), session (3 vs. 6) and treatment x session interaction for magazine-directed behaviors (magazine entries, probability to enter the magazine and latency to enter the magazine). Analyses were conducted separately for each experimental group (ST-Gq, GT-Gi). Bolded values indicate statistical significance, p<0.05.

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.042

-

Transparent reporting form

- https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.49041.043