The neural basis for a persistent internal state in Drosophila females

Abstract

Sustained changes in mood or action require persistent changes in neural activity, but it has been difficult to identify the neural circuit mechanisms that underlie persistent activity and contribute to long-lasting changes in behavior. Here, we show that a subset of Doublesex+ pC1 neurons in the Drosophila female brain, called pC1d/e, can drive minutes-long changes in female behavior in the presence of males. Using automated reconstruction of a volume electron microscopic (EM) image of the female brain, we map all inputs and outputs to both pC1d and pC1e. This reveals strong recurrent connectivity between, in particular, pC1d/e neurons and a specific subset of Fruitless+ neurons called aIPg. We additionally find that pC1d/e activation drives long-lasting persistent neural activity in brain areas and cells overlapping with the pC1d/e neural network, including both Doublesex+ and Fruitless+ neurons. Our work thus links minutes-long persistent changes in behavior with persistent neural activity and recurrent circuit architecture in the female brain.

eLife digest

Long-term mental states such as arousal and mood variations rely on persistent changes in the activity of certain neural circuits which have been difficult to identify. For instance, in male fruit flies, the activation of a particular circuit containing ‘P1 neurons’ can escalate aggressive and mating behaviors. However, less is known about the neural networks that underlie arousal in female flies. A group of female-specific, ‘pC1 neurons’ similar to P1 neurons could play this role, but it was unclear whether it could drive lasting changes in female fly behavior.

To investigate this question, Deutsch et al. stimulated or shut down pC1 circuits in female flies, and then recorded the insects’ interactions with male flies. Stimulation was accomplished using optogenetics, a technique which allows researchers to precisely control the activity of specially modified light-sensitive neurons.

Silencing pC1 neurons in female flies diminished their interest in male partners and their suitor’s courtship songs. Activating these neural circuits made the females more receptive to males; it also triggered long-lasting aggressive behaviors not typically observed in virgin females, such as shoving and chasing.

Deutsch et al. then identified the brain cells that pC1 neurons connect to, discovering that these neurons are part of an interconnected circuit also formed of aIPg neurons – a population of fly brain cells that shows sex differences and is linked to female aggression. The brains of females were then imaged as pC1 neurons were switched on, revealing a persistent activity which outlasted the activation in circuits containing both pC1 and aIPg neurons. Thus, these results link neural circuit architecture to long lasting changes in neural activity, and ultimately, in behavior. Future experiments can build on these results to determine how this circuit is activated during natural social interactions.

Introduction

Social behaviors are known to be affected by persistent internal states (Anderson, 2016; Berridge, 2004; Lorenz and Leyhausen, 1973). These states correspond with levels of arousal or drive, and can impact whether and how individuals interact, with consequences for mating decisions and reproduction (Chen and Hong, 2018; Kennedy et al., 2014; Stowers and Liberles, 2016). The neural mechanisms underlying arousal states remain largely unknown.

In male flies, a small population of male-specific neurons (P1) that express the sex-specific transcription factors Fruitless and Doublesex (Auer and Benton, 2016), drive both male-aggression and male-mating behaviors (Hoopfer et al., 2015; Koganezawa et al., 2016; von Philipsborn et al., 2011). Brief optogenetic activation of P1 neurons drives both persistent song production in solitary males and persistent aggression upon introduction of another male, both over minutes (Bath et al., 2014; Hoopfer et al., 2015; Inagaki et al., 2014). While P1 activation is sufficient for eliciting the persistent behavioral phenotypes, other groups of neurons, such as pCd (also called pC3 [Rideout et al., 2010]), are involved in maintaining the persistent state (Jung et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2019) - these neurons are not synaptically coupled to P1, and the circuit architecture that mediates persistence remains unresolved. P1 neurons also receive dopaminergic input that affects mating drive over longer timescales of hours (Zhang et al., 2016), suggesting neuromodulation is also important for persistent changes in behavior driven by P1. Work on P1 in flies bears some similarity to work in mice. In male mice, optogenetic activation of SF1 (steroidogenic factor 1) expressing neurons in the dorsomedial part of the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMHdmSF1) drive multiple defensive behaviors that outlast the stimulation by up to 1 min (Kunwar et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015). In addition, activity of VMHdmSF1 neurons can persist for over a minute following the presentation of a fear stimulus. Computational modeling work suggests a mix of recurrent circuitry and neuromodulation underlie the persistence (Kennedy et al., 2020), but this has not yet been tested.

We know little about the persistence of social behaviors in females across taxa. P1 neurons are a subset of the larger Doublesex+ pC1 neural subset (Kimura et al., 2008). While Drosophila females lack P1 neurons, they have Doublesex+ pC1 neurons (Rideout et al., 2010; Robinett et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2014), including a subset that are female-specific (Wu et al., 2019). Activation of pC1 neurons affects receptivity toward males (Wang et al., 2020b; Zhou et al., 2014), drives chasing of males (Rezával et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2019), and aggressive behaviors toward females (Palavicino-Maggio et al., 2019; Schretter et al., 2020). These data suggest that female pC1 neurons can drive an arousal state, similar to male P1 neurons, but whether female pC1 neurons can drive persistent changes in behavior and persistent neural activity, has not yet been investigated. Importantly, a complete electron microscopic volume is currently available for the entire adult female brain (Zheng et al., 2018), making it possible to link brain activity to complete wiring diagrams in females. Direct measurements of synaptic connectivity can determine whether recurrent neural networks, known to be important for persistent neural activity lasting for seconds (Aksay et al., 2007), also underlie minutes-long persistent activity and changes in behavior, as has been recently proposed for male mice and flies (Jung et al., 2020; Kennedy et al., 2020).

Here, we show that pC1 activation drives persistent changes in female behavior for minutes following stimulus offset, and we identify the subset of pC1 neurons (called pC1d/e [Wang et al., 2020a]; also referred to as pC1-Alpha [Wu et al., 2019]) that affects the persistent aggressive and male-like behaviors. A companion study Schretter et al., 2020 demonstrates that pC1d, but not pC1e, drives female aggressive behaviors. By leveraging the automated segmentation of an electron microscopic volume of the female brain (Dorkenwald et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2018), we map all inputs and outputs of both pC1d and pC1e and find a strong recurrent neural network with Fruitless+ aIPg neurons. Using pan-neuronal calcium imaging, we find that pC1d/e activation can elicit persistent activity for minutes among multiple cell types. The persistent activity is present in Doublesex+ and Fruitless+ neurons, including pC1 neurons themselves. We thus link minutes-long persistent neural activity and behavior with reciprocal connectivity in the female brain.

Results

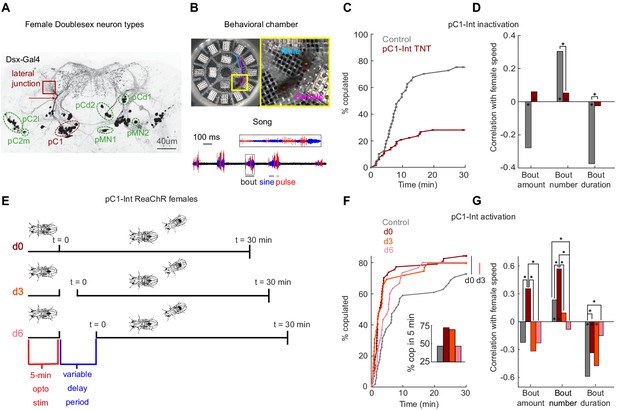

Female pC1 activation persistently modulates both female receptivity and song responses

To investigate the neural basis of a persistent internal state in the female brain, we focused on pC1 neurons, one of eight Doublesex-expressing cell types in the central brain (Figure 1A; Kimura et al., 2015). We used an intersection between two driver lines (Dsx-GAL4 and R71G01-LexA, hereafter referred to as pC1-Int; see Fly genotype table for list of genotypes used in this study), to label pC1 neurons, as done previously (Rezával et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2014) – prior work shows this line labels, per hemisphere, ~6 neurons, all of which project to the lateral junction (Zhou et al., 2014). We tracked male and female body parts (head and thorax) in addition to recording all sounds (Figure 1B, Figure 1—figure supplement 1A, Video 1; see Materials and methods for details on song segmentation and tracking of flies on a non-homogenous background). Silencing pC1-Int neurons in females affects receptivity Zhou et al., 2014; we corroborated these results (Figure 1C) and additionally showed that silencing pC1-Int neurons diminished responses to male song (Figure 1D). Persistent changes in the behavioral state of Drosophila males have been studied by examination of social behaviors following optogenetic activation of P1 neurons (Hoopfer et al., 2015; Jung et al., 2020). We activated pC1-Int in a solitary virgin female for 5 min, followed by a variable delay period, after which a virgin male was introduced to examine female behaviors in the context of courtship (Figure 1E) - there was no optogenetic activation following the first 5 min. The activity of stimulated neurons should decay during the variable delay period (d0 (0 min delay), d3 (3 min delay), or d6 (6 min delay)) – below, we test this explicitly with neural imaging, and also examine shorter activation periods. This paradigm therefore allowed us to examine the effects of differing levels of persistent activity on behavior.

pC1-Int activation has a persistent effect on female receptivity and responses to male courtship song.

(A) Dsx+ neurons in the female central brain. Max z-projection of a confocal stack in which Dsx+ cells are labeled with GFP (adapted from Deutsch et al., 2019). Dsx is expressed in eight morphologically distinct cell types in the female brain (seven types are indicated by circling of their somas; the more anterior cell type aDN [Lee et al., 2002] is not shown). pCd has two morphologically distinct types, pCd1 and pCd2 (Kimura et al., 2015). Many of these cells project to a brain region known as the lateral junction (red square). pC1 cells project to the lateral junction through a thin bundle (red arrow). This bundle was used to identify these cells in the EM dataset (see Figure 3—figure supplement 1). (B) Behavioral chamber (diameter ~25 mm) tiled with 16 microphones to record song. Male and female positions were tracked (a 1.5 s example trace is shown for the male (cyan) and female (magenta)), and male song was automatically segmented into sine and pulse (below). (C) Percent of male/female pairs that copulated as a function of time. Cox proportional hazards regression p=6.3*10−6: pC1-Int TNT (red, n = 68 pairs) compared with controls (gray, n = 40 pairs). (D) Rank correlation between male song (bout amount, number and duration) and female speed for pC1-TNT females (dark red) or control females (gray) paired with wild-type males. Significance between experimental groups was measured using ANOCOVA and multiple comparison correction (*p<0.01). An asterisk on a bar indicates a significant correlation between a single male song measure and female speed (*p<0.01). (E) Experimental design for pC1-Int activation. pC1-Int cells were activated (using ReaChR) for 5 min in a solitary female placed in the behavioral chamber. Following light offset, a wild-type male was introduced at t = 0, following a variable delay period (d0 = no delay; d3 = 3 min delay; d6 = 6 min delay). All behavioral phenotypes were measured at t > 0. (F) Same as (C), but for females expressing ReachR in pC1-Int cells according to the protocol shown in (E). Inset: The percent of pairs copulated between t = 0 and t = 5 min for each condition. pC1-Int activated females in the d0 condition (n = 57) copulated significantly faster than controls (n = 51; vertical black line; p=0.0045, Cox’s proportional hazards regression model, accounting for censoring, as not all flies copulated in 30 min; black vertical line). Time to copulation was also shorter in the d3 group (n = 39 pairs) compared with controls (d0, no ATR), but the difference was not significant after Bonferroni correction (p=0.034; red vertical line), and no significant difference was found between the 6 min delay (n = 30) and control groups (p=0.21). (G) Same as (D), but for females expressing ReachR in pC1-Int cells according to the protocol shown in (E). Asterisks show significance, using the same criteria as in (D). Numbers of pairs are the same as in (F).

Confidence maps (head in blue, thorax in orange) and part affinity vector fields (white arrows) calculated using LEAP (Pereira et al., 2019) for the male and female.

The male has a white painted dot on his back. Male chasing and singing are shown, as well as female shoving. Movie is slowed down four times.

Experimental flies were fed all-trans-retinal (ATR), which is required for ReaChR (red-shifted Channelrhodopsin) function in flies (Inagaki et al., 2014). Control flies shared the same genotype but were not fed ATR. We found that activation of pC1-Int neurons induces a persistent effect on female receptivity and responses to male song, but that this effect diminishes with a delay period between neural activation and introduction of a male. pC1-Int-activated females copulated significantly faster than controls in the d0 condition, with reduced copulations following a delay between optogenetic activation and introduction of a male (Figure 1F). About 75% of the flies copulated within 5 min in the d0 and d3 conditions, compared with fewer than 50% in the control and d6 groups (Figure 1F, inset). Another set of Dsx+ neurons called pCd1 (Figure 1A) was also shown to control female receptivity (Zhou et al., 2014) and, additionally, to enable P1-induced persistent activity in males (Jung et al., 2020). While we confirmed that pCd1 silencing in females reduced receptivity (Figure 1—figure supplement 1B), we found that 5 min pCd1 activation had no persistent effect on female receptivity (Figure 1—figure supplement 1C).

Activating pC1-Int also produced a persistent effect on responses to male song, overall with the strongest effect at the d0 delay (Figure 1G) - d0 females, in comparison with controls, accelerated more in response to all song elements, behaving like unreceptive females (Coen et al., 2014). This effect was not due to changes in wild-type male song structure for the d0 condition, although male song bouts were shorter and less frequent in the d3 and d6 conditions (Figure 1—figure supplement 1D), possibly due to the strong effect of pC1-Int activation on male-female interactions at longer delays, as shown below. Because at d0, females are both hyper-receptive (mate quickly) but also accelerate in response to song, we suspect that different subsets of pC1 neurons may control these two effects.

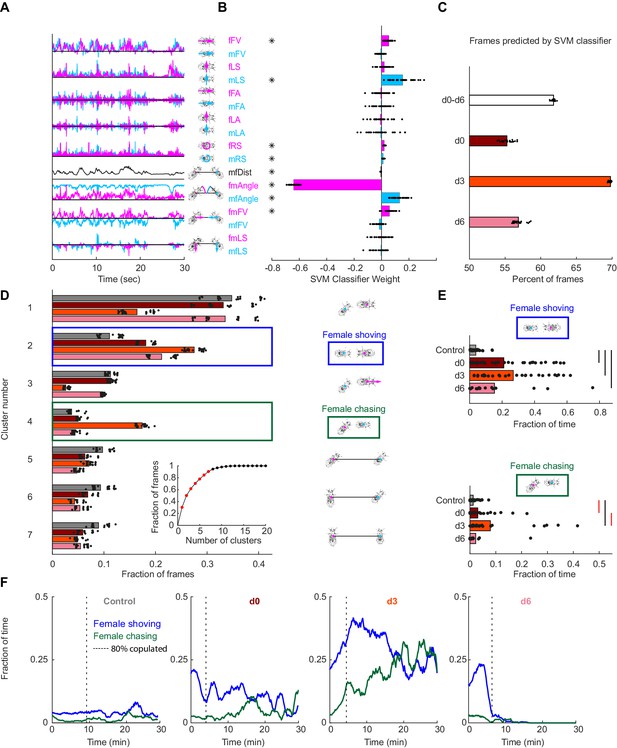

Female pC1 activation drives persistent female shoving and chasing

To quantify other behaviors elicited by pC1-Int activation, we used an unsupervised approach, and first decomposed male and female movements and interactions into 17 parameters (Calhoun et al., 2019; Figure 2A). We then used a Support-Vector Machine (SVM) framework (Cortes and Vapnik, 1995; Cristianini and Shawe-Taylor, 2000) to find the weights that best classify single frames as belonging to sessions of control vs experimental groups (all delay conditions, d0-d6). We found that the weights of 8 out of 17 parameters were significantly different from zero (Figure 2B and Figure 2—figure supplement 1A), with the strongest weight being fmAngle, defined as the degrees the female needs to turn in order to point toward the male centroid. The weight of fmAngle is negative because this parameter is smaller in the experimental flies compared with controls, indicating that pC1-Int activated females spend more time facing the male (Figure 2—figure supplement 1B). When separated by experimental condition, the SVM classifier performed best on the d3 condition versus control (Figure 2C), indicating that male-female movements and interactions are most distinct following this delay.

Automated identification of persistent female behaviors following pC1-Int activation.

(A) For each video frame, 17 parameters were extracted based on tracking of male/female position and heading (see Materials and methods for parameter definition). An example trace (30 s) is shown for each parameter. (B) 30 independent (using non-overlapping sets of video frames) Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifiers were trained to classify frames (each frame represented by 17 values) as belonging to control or experimental group (all delays d0-d6 considered together; see Materials and methods). Each classifier is represented by 17 points - one for each parameter. Each point is the weight associated with a given parameter for one classifier, and the bar height represents the mean over classifiers (*p<10−4, one-sample t-test with Bonferonni correction for multiple comparisons; see Materials and methods). (C) The percent of frames correctly classified using the SVM classifier. Each dot is the prediction of a single SVM classifier, trained to classify frames as belonging to control or experimental group (d0, d3, d6, or d0-d6 together) – 30 classifiers and their mean plotted for each group. (D) K-means was used to cluster frames based on the eight most significant parameters (marked with asterisks in (B)). The largest 7 clusters include 90.4% of the frames (see inset). Clustering was performed 30 times (black dots; bars = mean), using different but overlapping sets of frames. The same number of frames was taken from each group (see Materials and methods). Cluster 2 (blue box - ‘female shoving’) is more probable following pC1-Int activation (in d0, d3 and d6 conditions) compared to control, while cluster 4 (green box- ‘female chasing’) is more probable in the d3 condition only compared to control. At right, schematic describing the male-female interaction in each cluster, based on the mean values of the weights. (E) JAABA-based classification of shoving (top) and chasing (bottom) behaviors. Each dot represents a single pair of flies. The fraction of time the male-female pair spent shoving (0.037/0.21/0.27/0.15 for control/d0/d3/d6) or chasing (0.013/0.030/0.079/0.022) are shown. Black lines represent significant differences with p<0.05 after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison. Red lines - significant before, but not after correction for multiple comparisons. (F) Fraction of time females spent chasing or shoving (moving average with a 2-min window), based on JAABA classification in each condition (control, d0, d3, d6). T = 0 is the time the male was introduced (see Figure 1E), and the vertical dashed line indicates the time, for each condition, when 80% of the pairs copulated. Behaviors are not scored after copulation.

Next, we clustered individual video frames based on the values of the eight parameters identified as most important by the SVM (Figure 2—figure supplement 1A, asterisks), and found that the largest seven clusters accounted for over 90% of all frames (Figure 2D, inset). The weights of the eight parameters were different for each cluster (Figure 2—figure supplement 1C), representing different behaviors. Five of the clusters describe behaviors that are the same or reduced following pC1-Int activation (clusters 1 and 3, male chasing female, and 5–7, increased male-female distance). Two clusters, however, describe behaviors that occur with higher probability following pC1-Int activation (clusters 2 and 4; Figure 2D). Cluster 2 is characterized by small fmAngle and small mfAngle (indicating that the male and female are facing each other), decreased male-female distance, and large fmFV (indicating that the female is close to the male and moving in his direction). Cluster 4 is characterized by small fmAngle and large mfAngle (indicating that the female is behind the male), decreased male-female distance, and large fmFV (indicating that the female is moving in the direction of the male). Based on the weight values, and verified by inspection of the videos following clustering (Video 2), we termed cluster 2 ‘female shoving’ and cluster 4 ‘female chasing’. For both female shoving and female chasing, the amount of each behavior was highest in the d3 condition relative to control (Figure 2D).

A sequence of female shoving and chasing.

The female shoves the male while occasionally extending one or two wings, and then chases the male while occasionally extending a single wing or contacting the male with her front legs. Finally, the male attempts to copulate, the female spreads her wings, and copulation occurs. Movie is in real time. Experimental condition: pC1-Int, d0.

We then used JAABA (Kabra et al., 2013) to train a classifier to recognize epochs (groups of video frames) of female chasing and female shoving in the data (Figure 2—figure supplement 1D; see Materials and methods). This analysis confirmed that the amount of female shoving and chasing was greatest in the d3 condition relative to control (Figure 2E), in addition to revealing that the duration of female chasing and shoving bouts was longer (Figure 2—figure supplement 1E). In many cases females transitioned directly between shoving and chasing, and the conditioned probability (transition probability, given that a transition occurred) for shoving →chasing was more than double at the d3 condition compared to the d0 and d6 conditions. By examining shoving and chasing probabilities over time (Figure 2F), following the introduction of a male (t = 0), we found that both behaviors persisted for as long as 30 min in the d3 condition (Figure 2F), but not in the d0 and d6 conditions, suggesting a complex interaction between neural activity in the female brain at the time of introduction of the male and feedback or social cues. While the percent of time females spent shoving or chasing in the first two minutes after the male was introduced was similar in the d0 and d3 conditions (19.7/21.3% for shoving, 2.8/3.1% for chasing), shoving and chasing probabilities rose over time in the d3, but not in the d0 condition. In the d6 condition, shoving probability was comparable to the probability in the d0-d3 conditions in the first two minutes (15%), but decayed to control level after 6 min. The transition into ‘chasing’ from ‘shoving’ or from ‘other’ (no shoving and no chasing) epochs also peaked at d3 (Figure 2—figure supplement 2). In all cases, we only examined female behaviors prior to copulation. We also activated another Dsx+ cell type, pCd1, which is part of a circuit that drives persistent behavior in the male brain (Jung et al., 2020), but observed neither shoving nor chasing following 5 min of pCd1 activation in females (Figure 2—figure supplement 2A). This suggests that the persistent behavioral effects we observe are specific to pC1 activation.

Manual inspection of the videos identified several additional behaviors produced by females following pC1-Int activation (Figure 2—figure supplement 3). These include ‘female approaching’, ‘circling’, ‘head-butting’, and ‘female wing extension’ (Figure 2—figure supplement 3A–D; Videos 2 and 3). We found that some of these behaviors were coupled; for example, ‘circling’ was often preceded by ‘female shoving’ (Figure 2—figure supplement 3B, inset and Video 3) and ‘female wing extension’ was often coincident with ‘female chasing’ (Figure 2—figure supplement 3E and Video 2), similar to male behavior during courtship (although we did not observe sounds from the females that resembled male courtship song (Figure 2—figure supplement 3D)). Our automated behavioral classifier did not find these behaviors because we only tracked the head and thorax of each fly, which did not provide enough information to automatically identify these behaviors, or to keep accurate track of identities during behaviors in which the male and female often overlap (e.g., during ‘circling’).

Multiple example behaviors: female approaching (Figure 2—figure supplement 3A), shoving and circling (Figure 2—figure supplement 3B), female headbutting and female mounting (Figure 2—figure supplement 3C).

Following female approaching in this example, there is a short epoch of circling. In the ‘shoving and circling’ example, the female shoves the male before a circling behavior starts (See Figure 2—figure supplement 3B, inset). In the female headbutting example, the female extends two wings while headbutting the male, followed by a male jump. In the ‘female mounting’ example, the female positions herself behind the male and climbs on his back. Circling and headbutting examples are from pC1-Int (d0) condition, and female approaching/mounting from pC1-Int (d3) condition.

In sum, we found that for minutes following pC1-Int activation, females produced a variety of behaviors directed at the male. Some of these appear aggressive, such as shoving and head-butting (Nilsen et al., 2004; Palavicino-Maggio et al., 2019; Schretter et al., 2020), while others resemble male courtship behaviors, such as chasing and unilateral wing extension (albeit without song). These behaviors typically peaked in the d3 condition, where they remained high after male introduction. In contrast, the effect on female receptivity and female responses to male song, were both strongest in the d0 condition, ruling out the possibility that the effect on female receptivity is an indirect consequence of modified male courtship behavior in response to changes in female behaviors. Below we identify the pC1 cell types that drive persistent shoving and chasing, determine that they are part of a recurrent neural network using a new EM connectomic resource, and demonstrate that they can drive persistent neural activity on timescales similar to behavior.

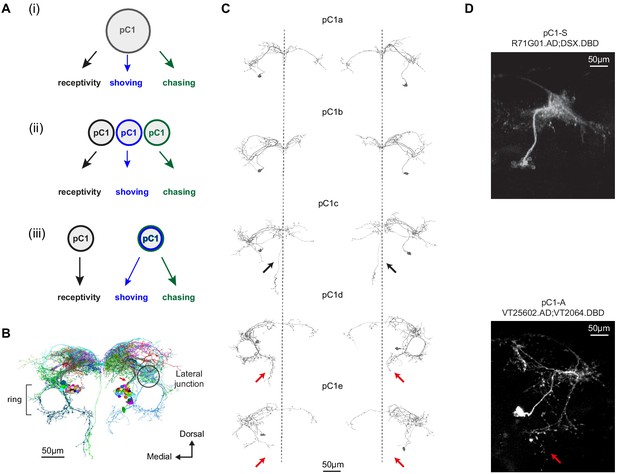

pC1 cell types

We propose three possible circuit configurations to explain our behavioral results (Figure 3A). In the first configuration, the same set of pC1 neurons activate different downstream circuits, each one controlling a different behavior. The differences in the temporal dynamics arise downstream of pC1. In the second configuration, three non-overlapping subsets of pC1 neurons control the different behaviors. In the third configuration, one pC1 subset controls female receptivity (that peaks at d0), and another set controls chasing and shoving (both peaking at d3). The second and third models assume some functional heterogeneity in the pC1 population. To evaluate these circuit models, we examined the behavioral consequences of activating distinct subsets of pC1 neurons. To define pC1 cell types, we used automated reconstruction of neurons in an EM volume of a female brain (FAFB; Zheng et al., 2018); neuron segmentation and reconstruction were accomplished using a novel platform for visualization and proofreading called FlyWire (Dorkenwald et al., 2020). We examined the morphologies of neurons that send projections to the lateral junction through a thin neuronal bundle, as pC1 neurons are known to (Figure 1A, red arrow; Figure 3B, red arrow; see also Deutsch et al., 2019 and Zhou et al., 2014).

Defining pC1 cell types.

(A) Models of how pC1 cell types control female receptivity, shoving, and chasing. In (i), a homogenous pC1 population drives three distinct behaviors, and in (ii) and (iii) pC1 is a heterogenous group, with different behaviors controlled by different pC1 subsets. (B) EM reconstruction of pC1 cells and other example neurons that pass through a cross section in the pC1 bundle. See Figure 3—figure supplement 1 for all the cells that pass through the pC1 bundle, including neurons that project to the lateral junction (considered pC1 cells), and neurons that do not project to the junction (not considered pC1 cells). (C) Five pC1 cell types identified in FlyWire, mostly consistent with (Wang et al., 2020a). The medial projection in pC1c (see black arrows) is ipsilateral to the soma in one cell and contralateral in the other, likely reflecting variability between individual cells. Both pC1d and pC1e share a horizontal projection from the ring, but only pC1d cells have an extra vertical projection (red arrows indicate difference between pC1d and pC1e projections). The right pC1e cell is also missing part of the ring. (D) (top) Split GAL4 line pC1-S (R71G01.AD∩DSX.DBD; n = 8, 7.7 ± 5 cells per hemisphere) and (bottom) Split GAL4 line pC1-A (VT25602.AD∩VT2064.DBD; n = 7, 2 ± 0 cells per hemisphere). Neurons express GFP and are labeled with anti-GFP, see Key Resources Table for full genotype. pC1-A has a medial projection (red arrow), similar to pC1d neurons found in EM (C); the medial projection was found in 7/7 imaged pC1-A female brains, in both hemispheres. The pC1d and pC1e projections were not found in pC1-S imaged female brains (8/8 brains). The medial projection that is unique to the pC1c subtype was missing in all the 8 pC1-S flies we imaged - therefore, it is likely that pC1-S includes only pC1a and/or pC1b cells.

We systematically checked all cell segments that pass through a cross-section in the pC1 bundle (Figure 3—figure supplement 1A) and excluded neurons that do not project to the lateral junction (Figure 3—figure supplement 1B–D), as all pC1 cells characterized so far project to the lateral junction (Kimura et al., 2015; Rezával et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2014). We found five pC1 cells per hemisphere (Supplementary file 1), consistent with the cell types found from manual tracing in the same EM volume (Wang et al., 2020a), although with differences in some projections (Figure 3C; one cell/hemisphere for pC1a-e was also found in the hemibrain, a second EM dataset of the adult female brain [Scheffer et al., 2020]).

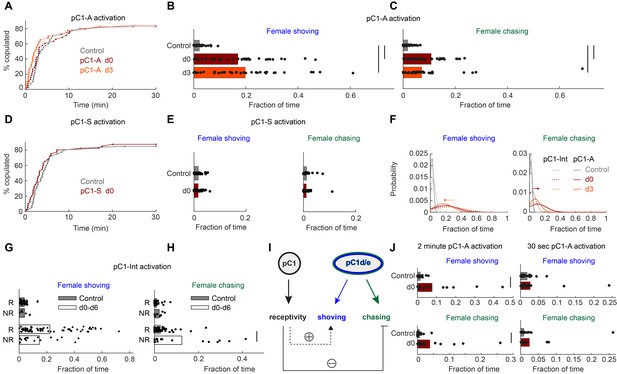

The effects of pC1 subtypes on behavior

We used genetic intersections to label two non-overlapping pC1 subpopulations. pC1-A labels a single pC1d and a single pC1e neuron in each hemisphere (Wu et al., 2019; same as line pC1dSS3 [Schretter et al., 2020]) and no cells in the VNC (Figure 3D and Figure 3—figure supplement 2; 2 ± 0, n = 7). The second intersection (pC1-S, a split-Gal4 intersection between Dsx.DBD Pavlou et al., 2016 and R71G01.AD; Figure 3D and Fly genotype table) does not label pC1d or pC1e cells, as evidenced by absence of the medial projections of pC1d/e neurons (Figure 3C–D). The pC1-S line labels 7.7 ± 4 pC1 cells per hemisphere in the brain, and no cells in the VNC (Figure 3—figure supplement 2C). All cells in the pC1-S line project to the lateral junction (Figure 3D).

Next, we tested if activation of these two non-overlapping pC1 sub-populations drives persistent behavioral phenotypes. Activation of either line pC1-A or pC1-S did not affect female receptivity (Figure 4A,D), but activation of pC1-A drove persistent shoving and chasing (Figure 4B–C), while activation of pC1-S did not (Figure 4E). These results are consistent with model 3 (Figure 3A), in which female receptivity and female shoving/chasing are driven by different populations, and also consistent with prior work, showing that 10 min of thermogenetic pC1-A activation drives persistent chasing in females (Wu et al., 2019). pC1d/e neurons are female-specific (Wu et al., 2019), and prior work reveals that pC1 neurons in females, but not males, respond to courtship song (Deutsch et al., 2019). Using in vivo whole-cell patch clamp recordings of neurons labeled in the pC1-A line, we found that pC1d/e neurons in virgin females depolarize in response to features in conspecific courtship song (Figure 4—figure supplement 1). This finding indicates that pC1d/e neurons can be activated during courtship by male song.

pC1d/e neurons drive female shoving and chasing, but do not affect receptivity.

(A) pC1-A activation did not affect copulation rates in either the d0 or d3 conditions (n = 40, 38, 40 for control/d0/d3; p=0.79 or 0.29 for control vs d0 or d3; Cox proportional hazards regression, see Materials and methods). (B, C) Shoving (B) and chasing (C) probabilities (control/do/d3: 0.02/0.17/0.20 and 0.018/0.11/0.07 for shoving and chasing) were significantly higher in both the d0 and d3 conditions compared to control (two-sample t-test; *p<0.05). (D–E) same as (A–C), but for pC1-S activation. pC1-S activation did not affect either copulation rate (D) or shoving or chasing (E) probabilities (control/do: 0.02/0.02 and 0.01/0.01 for shoving and chasing). (F) Probability distribution of the fraction of time the female spent shoving (left) or chasing (right) following pC1-A activation (solid line) or pC1-Int activation (dashed line). Arrows indicate the difference in peak shoving (at d3; two-sample t-test, p=0.11) or chasing (at d0; two-sample t-test, *p=4.5*10−4) probability, between pC1-Int and pC1-A activation. Bonferroni correction was used for multiple comparisons. (G) Fraction of frames with shoving for pairs in which females copulated (R - Receptive) or did not copulate (NR – Not Receptive) for all experimental conditions taken together (d0–d6). Each dot is a single pair, and the bar value is the mean over all pairs (p=0.92 and 0.13 for control and d0-d6). (H) Same as (G), for female chasing (p=0.13 and p<10−5 for control and d0-d6). (I) Female pC1d/e cells drive persistent shoving and chasing, but do not affect female receptivity. Female receptivity, controlled by a separate pC1 subset labeled in the pC1-Int line, suppresses female chasing, while possibly enhancing female shoving. (J) Shoving and chasing probabilities (control/d0: 0.077/0.015 and 0.039/0.006 for shoving and chasing; p=0.026 and 0.035; n = 20/20 for control/d0) were significantly higher in the d0 condition compared to control following 2 min of pC1-A activation, but not following 30 s (n = 20/21 for control/d0) of pC1-A activation (p=0.52 and p=0.24 for shoving and chasing).

When examining the fraction of time spent shoving or chasing across the three conditions (control, d0, and d3) to compare results of activating neurons in pC1-A and pC1-Int lines (Figure 4F), we found that levels of female chasing are increased with pC1-A activation (relative to pC1-Int) at d3. The levels of shoving are slightly decreased at d0, but this effect was not significant. This suggests that pC1 cell types in the pC1-Int driver, other than pC1d/e (and other than the cells in the pC1-S driver), have a modulatory effect on the shoving and chasing behaviors, at distinct timepoints.

pC1-Int, but not pC1-A, activation drives persistent female receptivity (Figure 1F vs Figure 4A), indicating that pC1-Int cells other than pC1d/e drive female receptivity (although high copulation rates in control flies could mask a potential effect of pC1-A on female receptivity). We hypothesized that the same pC1-Int cells that drive female receptivity, also affect the probability of shoving and chasing. If true, we would expect a different rate of shoving and chasing in receptive and non-receptive females. Indeed, we found that following pC1-Int activation, females that eventually copulated (receptive) showed a slightly higher level of shoving compared with females that did not eventually copulate (unreceptive), although this effect was not statistically significant (Figure 4G). In contrast, receptive females showed a strong and significant reduction in chasing (Figure 4H). Taken together, our results suggest that cells within the pC1-Int line that control receptivity modulate the amount of female chasing (and possibly also shoving) (Figure 4I). We also tested shorter activation durations and found robust persistent shoving and chasing following 2 min activation, but reduced persistent shoving and chasing following 30 s activation (Figure 4J). Below we address how minutes-long pC1d/e activation affects neural activity.

pC1d is reciprocally connected to a specific subset of Fruitless+ neurons

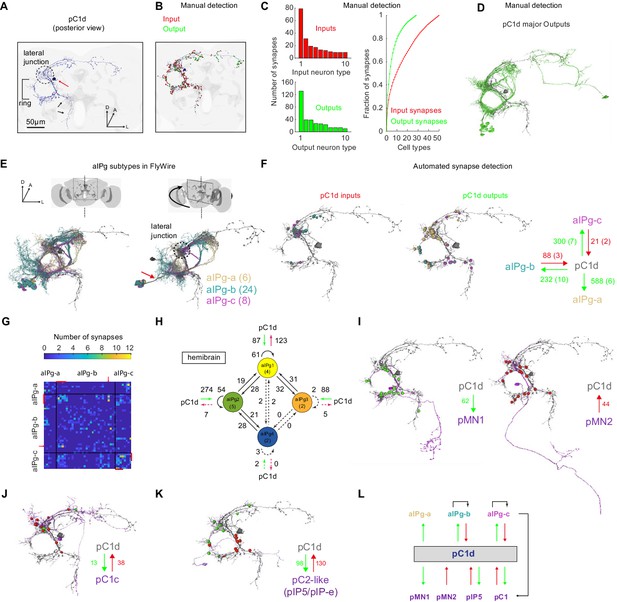

The pC1-A line (same as pC1dSS3 [Schretter et al., 2020]) includes two cells per hemisphere, one pC1d and one pC1e cell. Schretter et al., 2020 have demonstarted that optogenetic activation of genetic lines that contain pC1d, but not pC1e, drive female aggressive behaviors, such as those we refer to here as ‘shoving’. We therefore first focused on pC1d, and mapped the major inputs and outputs, searching for circuit motifs that could account for pC1d’s ability to drive a persistent behavioral state in females. We used automated reconstruction of all neurons within an EM volume of an entire adult female brain called FAFB (Zheng et al., 2018; Dorkenwald et al., 2020). This volume contains both brain hemispheres, enabling complete reconstruction of pC1d cells that send projections across the midline (Figure 3C). Focusing on a single pC1d cell (Figure 5A) we first manually detected synaptic connections (Figure 5—figure supplement 1A; see Materials and methods), as done previously for other circuits in FAFB (Felsenberg et al., 2018; Sayin et al., 2019; Zheng et al., 2018) - while our manual detection process was unbiased, in that we looked for synapses between pC1d and any other overlapping segment in FlyWire (see Materials and methods), we only sampled a subset of all pC1d synapses (see below for analysis based on automated synapse detection). After proofreading the pC1d cell and its input and output cells, and excluding neurons with weak connections (using three synapses as a threshold, see Materials and methods), we counted a total of 417 presynaptic and 421 postsynaptic sites (Figure 5B, Video 4). We sorted all pC1d synaptic partners by cell type, based on morphology, and examined the distribution of synapses by type for input (presynaptic partners) and output (postsynaptic partners) neurons separately (Figure 5C). The three output types with the largest number of synapses with pC1d share a common morphology: all pass through a single neurite bundle (Figure 5D–E, Figure 5—figure supplement 1B–C and Video 5) and all send projections to the ring (Figure 5A), including dense projections in the lateral junction (Figure 5E).

The connectome of pC1d reveals recurrent connections with aIPg neurons.

(A) The left pC1d cell (posterior view) reconstructed in FlyWire following automated segmentation and manual proofreading. The cell body is marked with a red arrow, and the pC1d long medial projection (that does not exist in other pC1 types) is marked with black arrows. (B) Same cell as in (A), with manually detected synapses. Neurons pre-synaptic (inputs to pC1d) are marked in red, and neurons post-synaptic (outputs of pC1d) in green. After excluding segments connected to pC1d with less than three synapses, we counted 417/421 manually-detected input/output synapses (see also Video 4). (C) Left: pC1d inputs (66 cells) and outputs (50 cells) were classified into cell types based on morphology. The number of input (top) or output (bottom) synapses are shown for each cell type, sorted (separately for inputs and outputs) based on the total number of synapses with pC1d for each type. Right: The cumulative fraction of synapses counted as a function of the number of cell types included (calculated separately for inputs/outputs). The three most common output types encompass 49.4% of all output synapses, while the three most common input types encompass 30.5% of all input synapses. (D) The cells that belong to the most common cell types (50% of all output synapses) are shown for pC1d output cells. Note that pC1d has postsynaptic connections with both left (ipsilateral to cells body) and right (contralateral) aIPg cells. (E) Left: Posterior view (same as in (A)) of pC1d (gray) and aIPg cells. Right: rotated view, showing the separation between three subtypes of aIPg cells (6/24/8 for aIPg-a/b/c), sorted according to their projections. See Table 1 for the full list of FlyWire detected aIPg cells in one hemisphere. (F) Synapses between pC1d (gray) and individual example aIPg cells, color coded by aIPg type as in (E). Total synapse count for each type is summarized. Synapses were detected automatically (Buhmann et al., 2019). Only cells with six synapses or more with pC1d are included in the analysis (See Materials and methods and Table 1 for more details). (G) Connection matrix between pairs of aIPg cells. The number of synapses (Buhmann et al., 2019) between a given pair of aIPg cells are indicated with a colorscale. Black lines separate aIPg subtypes. Red lines denote the aIPg cells that are reciprocally connected with pC1d (with si synapses or more each way), and red arrows indicate an aIPg-b cell that is reciprocally connected to cells that form reciprocal connections with pC1d. (H) The number of synapses within and between groups of aIPg cells based on the fly hemibrain connectome (Scheffer et al., 2020). The number in parentheses indicates the number of cells per group (aIPg-1–4). Round arrows indicate within-group connections (e.g. 61 synaptic connections between pairs of aIPg-1 cells). Dotted arrows are shown for weak connections (under five synapses). (I) pC1d connections with Dsx+ pMN1 and Dsx+ pMN2 cells. (J) An example Dsx+pC1 cell (type pC1c) that is recurrently connected to pC1d. (K) pC1d connections with pC2-like cells (with similar morphology as hemibrain pIP5 neurons or Fru+ pIP-e clones from Cachero et al., 2010). (L) pC1d is a hub connecting Dsx+ or Fru+ pC1, pIP5, pMN1, and pMN2 neurons with Fru+ aIPg neurons.

A single pC1d neuron, automatically traced and manually proofread.

Inputs (post-synaptic terminals, manual detection) are shown in red, outputs (pre-synaptic terminals, manual detection) in green (see also Figure 5A–B).

pCd (blue) is shown with example aIPg-a,b,c cells.

Synapses (detected manually) are marked in red for inputs (to pC1d) and in green for outputs. Cell type colors (yellow, cyan, magenta) are shown for aIPg-a,b,c as in Figure 5E–F and Figure 5—figure supplement 1.

The top matches (using NBLAST [Costa et al., 2016]) for all three types were sexually dimorphic Fru+ neurons called aIP-g (Figure 5E and Figure 5—figure supplement 1B, see Cachero et al., 2010). FlyWire cells that share the aIP-g morphology were sorted into three types, aIPg-a, aIPg-b, and aIPg-c, based on the three separate bundles through which their projections pass (Figure 5E). According to our manual synapse detection, aIPg-a cells have 131 sites postsynaptic to pC1d and only five presynaptic sites, while aIPg-b,c cells have stronger reciprocal connections with pC1d, with an output:input ratio of ~1:1 (38:39) for aIPg-b, and 2.8:1 (39:14) for aIPg-c.

FlyWire provides a mapping of the publicly available, automatically detected synapses from Buhmann et al., 2019; see Materials and methods for details. We re-evaluated synaptic partners using automatic detection, and focused on cells with strong connections with pC1d using two criteria: (1) minimum of six synapses, (2) the cell belongs to a cell type (based on morphology) with at least one cell with 15 synapses or more with pC1d. Consistent with manual detection, we found that aIPg-a cells are postsynaptic to pC1d, while aIPg-b,c are reciprocally connected to pC1d (Figure 5F). Some cells from the aIPg-b,c groups are also interconnected (Figure 5G). Interestingly, the most interconnected cells within the aIPg-b group were also the ones that are reciprocally connected to pC1d (Figure 5G, red lines).

We also examined synaptic connectivity between pC1d and aIPg cells in a second EM database that consists of a portion of the adult female brain (the ‘hemibrain’ [Scheffer et al., 2020]), and found a set of 13 neurons identified as aIPg (also evaluated in [Schretter et al., 2020]), compared with 39 neurons we identified as aIPg in FlyWire. Twelve of these aIPg cells (denoted as types aIPg1-3 in the hemibrain) share the aIPg-b morphology (Figure 5—figure supplement 1D), and are synaptically connected to pC1d (excluding one connection with less than three synapses). One (aIPg4) shares the aIPg-c morphology. Consistent with our results in FlyWire, pC1d in the hemibrain has more presynaptic sites than postsynaptic sites with aIPg-b (hemibrain aIPg1-3) cells, and aIPg-b neurons form many recurrent connections with each other (Figure 5H). Note that while our classification of aIPg cell types was based on morphology alone, the classification in the hemibrain is based on both morphology and connectivity. In the hemibrain v1.1, we found additional cells that match (morphologically) neurons we term aIPg-a and aIPg-c – these neurons are called SMP555/556 and SMP558, respectively.

Finally, in FlyWire, we found that pC1d forms connections with other Dsx+ cells, including direct connections with pMN1 (DNp13) and pMN2 (vpoDN) (Figure 5I), other pC1 cells (Figure 5J), and pC2-like cells with similar morphology to Fru+ pIP5 cells (Figure 5K, Video 6 and Supplementary file 1). These results indicate that pC1d may serve as a hub within the central brain for Dsx+ and Fru+ neurons (Figure 5L).

pC1d (blue) is shown with neurons that have a similar morphology as known female Doublesex-expressing cells.

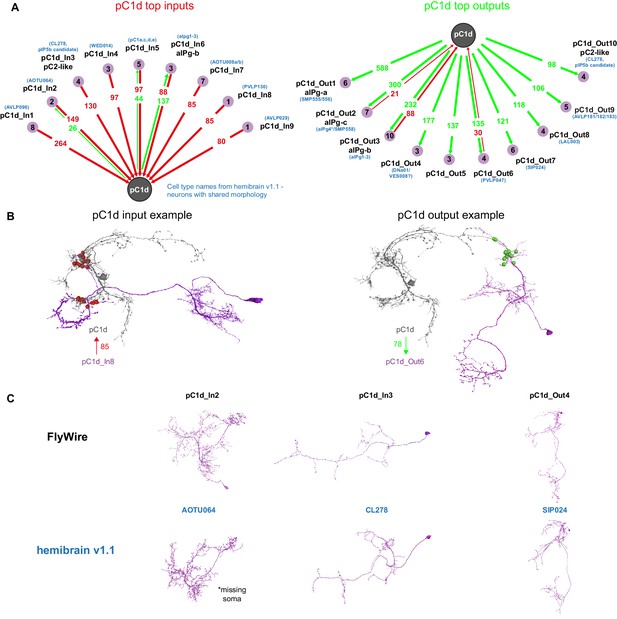

Using automated synapse detection in FlyWire, we examined all the major inputs and outputs of both pC1d (Figure 6A) and pC1e (Figure 6—figure supplement 1), as our driver line pC1-A labeled both neurons in each hemisphere (see full list of inputs and outputs and public links to FlyWire neurons in Supplementary file 1). aIPg-b neurons have the most reciprocal connections with pC1d, and the three strongest output types of pC1d are aIPg-a (588 synapses), aIPg-c (300 synapses), and aIPg-b (232 synapses). The pC1d output:input ratio with aIPg (pC1d-to-aIPg:aIPg-to-pC1d) was 588:0 for aIPg-a, 2.6:1 for aIPg-b and 14.3:1 for aIPg-c (Figure 5F) – consistent with the results obtained by manual detection, showing that aIPg-b has the most ‘balanced’ reciprocal connectivity with pC1d. For pC1e (Figure 6—figure supplement 1), of the top inputs and outputs, the only reciprocal connections were with aIPg-b. Shared inputs between pC1d and pC1e also include pC1a, a cell previously shown to control female receptivity (Wang et al., 2020b). Shared outputs include aIPg-a,c, and cell types that share the hemibrain morphology of SIP024 and LAL003. Some of the top connections of pC1d were cross-hemispheric neurons or neurons with synapses contralateral to pC1d (Figure 6B) – these neurons and connections fall outside of the volume of the hemibrain. However, several of the top inputs and outputs could be identified in the hemibrain, and we have indicated the corresponding cell type name where we could find matches (Figure 6 and Figure 6—figure supplement 1). Seven of the aIPg cells that are pC1d synaptic partners, also synapse with pC1e (Figure 6—figure supplement 1).

pC1d synaptic partners based on automated synapse detection in FlyWire.

(A) The top (≥80 synapses) pC1d inputs (left) and outputs (right). The number of pC1d presynaptic (input) and postsynaptic (output) connections are shown in red/green. The number of input or output cells that are connected to pC1d with six synapses or more (see Materials and methods) are indicated in the purple circles. Cells with shared morphology were identified in hemibrain v1.1 (names shown in blue) for each cell type. As the number of synapses is counted per type and only for cells with six synapses or more, separately for the inputs and outputs, the numbers between the left and right plots do not necessarily match (see Table 1 for more details). (B) Example cells that are connected to pC1d. pC1d_In8 synapses onto pC1d on a branch ipsilateral to pC1d soma, but pC1d_In8 has its soma and dendrites in the contralateral hemisphere. pC1d_Out6 connects to pC1d on a branch contralateral to the pC1d soma. (C) Example pC1d input or output cells in FlyWire, compared to similar cells in the hemibrain v1.1.

As recurrent connectivity between neurons is known to support persistent neural activity (Goldman-Rakic, 1995; Major and Tank, 2004; Zylberberg and Strowbridge, 2017), we next examined whether activating pC1d/e could drive long-lasting changes in brain activity, with a spatial distribution that matches the pC1d or pC1e connectomes.

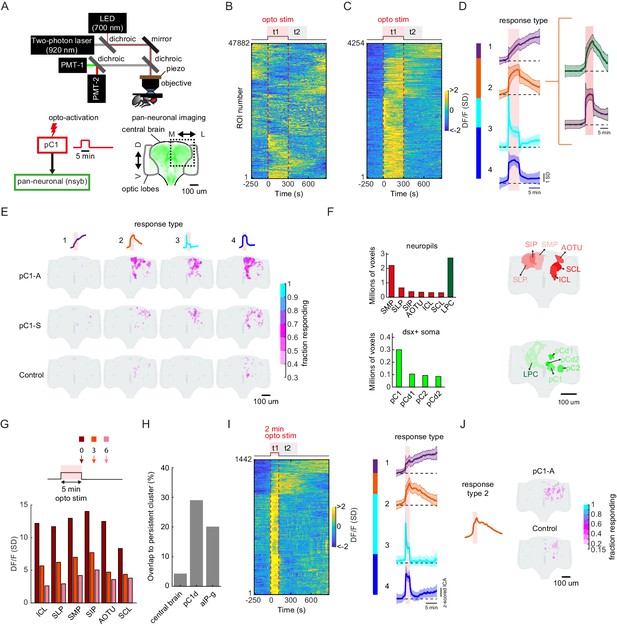

Activation of pC1d/e neurons drives persistent neural activity

Persistent neural activity is defined as activity that continues after a triggering stimulus ends (Zylberberg and Strowbridge, 2017). To relate our findings above to persistent neural activity, we first activated either neurons in the pC1-A or pC1-S lines using 5 min of optogenetic stimulation (similar to behavioral experiments, see Materials and methods), and imaged responding cells via GCaMP6s expressed pan-neuronally (Figure 7A). To compare activity across flies and to map activity onto a reference atlas, we used a recently developed pipeline for two-photon volumetric calcium imaging, motion correction, registration, and region-of-interest (ROI) segmentation (Pacheco et al., 2021), and scanned the entirety (in the anterior-posterior axis) of the dorsal half of a single brain hemisphere (either left or right) in each fly (Figure 7A) – we mirrored all activity onto one hemisphere for display. We measured neuronal activity during the 5 min of optogenetic activation in addition to 9.5 min following activation offset (Video 7), and found that out of 47,882 ROIs with activity segmented across 28 brains and all genotypes (Figure 7B; see Materials and methods), 4254 ROIs showed significant responses to optogenetic stimulation (Figure 7C; Ft1 > 3σ0, σ0 = standard deviation of activity during baseline).

pC1d/e neurons drive persistent neural activity in the central brain.

(A) Experimental setup. pC1 cells (pC1-A or pC1-S) expressing csChrimson were activated through the objective using an LED (700 nm). GCaMP6s and tdTomato were expressed pan-neuronally using the nsyb driver, and a custom-designed two-photon microscope was used to image brain activity before, during and after pC1 activation (see Key Resources Table for genotypes and Materials and methods for more details on the experimental setup). (B) Brain activity recorded in response to optogenetic stimuli (n = 28 flies, all genotypes). GCaMP6s signal was motion corrected and 3D-ROI segmented based on correlated activity in neighboring voxels (see Materials and methods). The z-scored signal of all ROIs (n = 47882 ROIs from both pC1-S and pC1-A activation and control experiments) are plotted in units of standard deviations (see scale bar), and shown 5 min before activation, during activation (t1), and 9.5 min post-activation (t2 marks the first 5 min post-activation). Red dashed line depicts the optogenetic stimulus onset and offset. (C) pC1 activation evokes both transient and persistent activity. Subset of ROIs from panel (B) were selected based on mean z-scored activity during (t1) and after photoactivation (t2), and ROIs were sorted by hierarchical clustering of temporal dynamics. We found 4254 responsive ROIs, defined as ROIs with Ft1 > 3σo (σo - standard deviation during baseline, Ft1 is the mean fluorescence during t1), including transient (Ft2 ≤ 3σo, blue and cyan; Ft2 is the mean fluorescence during t2) or persistent (Ft2 >3σo, orange and purple) response types . (D) Mean ± SD for response types 1–4. In response types 1 and 2, the activity level (calcium response) persists after activation offset, while for types 3 and 4, the activity is high during, but not after photoactivation. The two major sub-clusters of response type 2 are shown at right. (E) Maps of transient and persistent activity types. ROIs from response types 1–4 per animal were registered to an in vivo intersex atlas (Pacheco et al., 2021) to generate probability density maps across animals per brain voxel (each voxel is 0.75 × 0.75 × 1 µm3). Activity maps are maximum-projected along the anterior-posterior axis, and overlaid onto the brain template, color coded by the fraction of flies showing activity at each voxel (ranging from 30% to 100%). We considered a voxel to consistently have a particular response type if active in over 30% of flies. Response type 2 shows persistent activity following pC1-A activation, and occupies 4.3% of the volume imaged, compared with 0.6% following pC1-S and 0.2% in control flies. (F) Brain regions containing persistent responses (type 2). We used both anatomical segmentation of the in vivo brain atlas (Pacheco et al., 2021) and segmentation of the Dsx+ circuit (also registered to the same atlas) into processes in the LPC and major groups of cell bodies (pC1, pC2, pCd1, pCd2) to assign ROIs to neuropils (red) or overlap with Dsx+ neurons (green). For each of these regions, we calculated the average number of voxels or volume (across-individuals) occupied by all ROIs belonging to response type 2, following pC1-A activation. Neuropils were sorted by the number of voxels, and the top six neuropils are shown. pC2m and pC2l are shown together as pC2, as they are not always spatially separable in females. For responses in other conditions (pC1-S, control) and other neuropils see Figure 7—figure supplement 1A. (G) Mean response (DF/F) over all flies and ROIs per brain neuropil from (F), at t = 0 (stimulus offset), t = 3 min and t = 6 min. Time points relative to stimulus are shown in arrows in the schematic. Each ROI's activity was z-scored relative to the baseline; therefore, DF/F units are plotted in standard deviation (SD) relative to baseline activity. (H) The percent of voxels that belong to the persistent cluster (response type 2) out of the volume imaged in the central brain (4.3%), out of the voxels that include pC1d (29.04%), or out of the voxels that include aIPg cells (20.14%); see Materials and methods – pC1d and aIPg neurons from FlyWire were registered into the in vivo atlas for comparisons. (I) Shorter duration (2 min) pC1-A activation also evokes both transient and persistent activity. ROIs for both control and pC1-A activation (using the same criteria as in (C)) could also be clustered into four response types (purple, orange, blue, and cyan) similar to (D). (J) Map of persistent activity type 2 upon 2 min pC1-A stimulation.

Maximum z-projection (60 μm in Z) of the calcium response in a female expressing GCaMP6s pan-neuronally.

Calcium response ((F(t) -Fo/Fo), color coded) is shown 5 min before, 5 min during and 9.5 min after pC1-A activation (using csChrimson). The movie is sped up 20 times.

We then clustered these ROIs based on response patterns (Figure 7D), which revealed four types of responses. Transient responses - ROIs with elevated activity during the optogenetic stimulus (t1), but not following the stimulus (t2) - could be grouped into two clusters (response types 3 and 4). The other two types showed sustained activity lasting at least 5 min after the optogenetic stimulus offset (response types 1 and 2; Ft2 > 3σ0, see Materials and methods). The temporal dynamics of persistent neural activity, continuing to at least 10 min following stimulation, is consistent with our observation of female shoving and chasing of a male introduced 6 min after stimulation offset (Figure 2E–F). In addition, response type 2 could be split into two clusters (Figure 6D, right) based on response temporal dynamics.

While response type 1 had low spatial consistency across animals, response types 2–4 showed higher spatial consistency, and the spatial distribution of ROIs differed between controls, pC1-S, and pC1-A activated flies (Figure 7E). Activation of pC1d/e neurons (in line pC1-A) drove persistent activity (response type 2) in more than 30% of the imaged flies, and in 24.7 times more voxels than in controls, and 6.8 times more voxels compared with pC1-S activation. Making use of neuropil segmentation of an in vivo brain atlas to which all ROIs were registered (Pacheco et al., 2021), we evaluated the distribution of pC1d/e-elicited activity by brain neuropil (Ito et al., 2014). Persistent activity (response type 2) was clustered in the posterior-dorsal portion of the brain spanning the Superior Medial, Lateral and Intermediate Protocerebrum (SMP, SLP, SIP), the Anterior Optic Tubercle (AOTU), and the Inferior and Superior Clamp (ICL and SCL; Figure 7F and Figure 7—figure supplement 1A); these brain regions contain a large number of projections from sexually dimorphic neurons expressing either Doublesex or Fruitless (Rideout et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2010). We found that 61% (4717/7759) of all the presynaptic terminals and 85% (3283/3848) of all the postsynaptic terminals for the group of 11 aIPg1-3 (all share the aIPg-b morphology) cells in hemibrain v1.1 are in these six areas, with the SMP, SIP, and AOTU being the most dominant input and output regions for the aIPg1-3 cells.

Our behavioral results indicated that female brain state must differ between the d0, d3, and d6 conditions (Figure 2F and Figure 4B–C) – we therefore quantified neural activity at these specific time points (0, 3 min, and 6 min) following optogenetic activation. In the neuropils with highest activity, we found that responses were highest immediately following stimulation (t = 0) and decayed significantly by t = 3 min, and further still by t = 6 min (Figure 7G; Figure 7—figure supplement 1B).

In order to measure the overlap of pC1-elicited activity with Dsx+ neurons, we generated anatomical labels for the lateral protocerebral complex (LPC), a diffuse brain area to which all Dsx+ neurons send their projections, and also for all major groups of Dsx+ somas (pC1, pC2l, pCd1, and pCd2) within the in vivo brain atlas (Figure 7F, see Materials and methods). We found that ROIs with persistent activity (response type 2) overlap with the LPC, in addition to the regions occupied by pC1 somas, and to a lesser extent with regions occupied by pC2, pCd1, and pCd2 somas, suggesting that Dsx+ pC1 neurons carry persistent activity. We also looked for overlap between ROIs with persistent activity and the projections of individual aIPg neurons, all registered into the same reference brain (Figure 7H; see Materials and methods). While persistent activity (response type 2; Figure 7D–E) spans only 4.3% of the central brain (Figure 7E; see Materials and methods), we found response type 2 activity in 20.14% (union of the overlap) of the voxels that include aIPg-a/b/c example cell (one of each type) from FlyWire (Figure 7H). In addition, activity driven by 5 min of activation was not aberrant. DF/F values following 5 min optogenetic activation (data from Figure 7C) fell within the distribution of DF/F values observed in separate experiments (Pacheco et al., 2021) in which activity was driven by auditory stimuli rather than optogenetic activation (Figure 7—figure supplement 1C).

We also examined persistent activity following a shorter activation period of 2 min, and found ROIs with persistent activity (response Type 2; Figure 7I–J). The persistent activity following 2 min activation was weaker in this condition compared to 5 min activation, suggesting that persistent activity scales with the activation period.

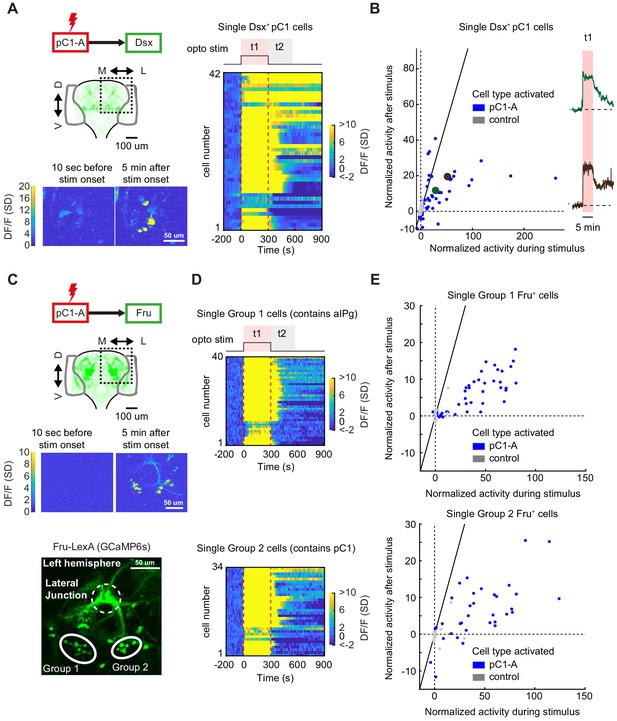

We next expressed GCaMP6s in only Dsx+ neurons, to confirm the specific Dsx+ cells with persistent neural activity – this is possible because Dsx+ somas are clustered by cell type (Figure 1A). We activated pC1d/e neurons for 5 min (Figure 8A and Video 8) and recorded activity in 273 cells (ROIs drawn manually) across 16 flies. We examined the responses during (t1) and after (t2) optogenetic stimulation (same as for the pan-neuronal dataset), and compared these responses to controls in which pC1d/e neurons were not activated (n = 11 flies, 192 ROIs; See Fly genotype table for full genotypes; Figure 8B). A number of Dsx+ pC1 cells showed strong persistent activity (Figure 8B; same definition as for the pan-neuronal screening, Ft2 > 3σ0) following optogenetic activation. We observed some heterogeneity in responses across the pC1 cells (Figure 8B), with some cells showing faster decay than others following stimulus offset, consistent with the two clusters underlying response type 2 (Figure 7D, green and brown). We did not observe persistent activity in any non-pC1 Dsx-expressing cell types (Figure 8—figure supplement 1), including pC2 neurons or pCd1 neurons, previously shown to be necessary for P1-induced persistent activity in males (Jung et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2019).

pC1d/e neurons drive persistent neural activity in Dsx+ and Fru+ cells.

(A) Left: Activation of neurons in the pC1-A line and imaging of neural activity in all Dsx+ cell bodies. Activity in Dsx+ pC1 somas is shown 10 s before stimulus onset and 5 min after stimulus onset for an example experiment. Right: Normalized activity of Dsx+ pC1 somas ((F(t) - F0)/σo; F0 and F(t) are mean Fluorescence during baseline and fluorescence over time, respectively). Chrimson and TdTomato are expressed in pC1-A cells. GCaMP6s is expressed in Dsx+ cells. pC1 somas imaged following pC1-A activation (along with controls) are both shown if Ft1 > 3σo (σo - standard deviation during baseline, Ft1 is the mean fluorescence during t1) (see (B) for full set of imaged pC1 neurons). (B) Left: Mean Calcium response in Dsx+ pC1 somas during t1 (x-axis) versus during t2 (y-axis) for pC1-A activation and control. Normalized activity is defined as (F - Fo)/σo, where Fo is the mean activity during baseline, σo is the standard deviation during baseline, and F is the mean activity during t1 for x and t2 for y. Each dot represents a single segmented soma. Dots above the dashed line represent persistent responses following activation. All imaged pC1 neurons are shown (n = 8 flies, 58 ROIs for pC1-A, n = 5 flies, 25 ROIs for controls). Right: Example traces of (F - Fo)/Fo from two individual pC1 cells, showing different response decays after stimulus offset (matching the results from Figure 7D). Corresponding points are enlarged and marked in green and purple in B (left). (C) Top: Activation of neurons in the pC1-A line and imaging of neural activity in Fru+ cell bodies. Bottom: Spatial pattern of Fru+ cell bodies imaged (here, a left hemibrain is shown (Z-projection of Fru+ neurons expressing GCaMP6s)). Fru+ cell body groups 1 and 2 are defined based on their spatial location - group 1 likely contains Fru+ pC2 and aIPg neuronal cell bodies, whereas group 2 likely contains Fru+ pC1 cell bodies (Figure 8—figure supplement 2). (D) Normalized activity of Fru+ somas from group 1 (Top) or group 2 (Bottom). (E) Mean activity in Fru+ cell bodies from group 1 (left, n = 9 flies, 46 ROIs for pC1-A, n = 5 flies, 13 ROIs for control) and group 2 (right, n = 9 flies, 37 ROIs for pC1-A, n = 5 flies, 24 ROIs for control) during t1 (x-axis) versus during t2 (y-axis) following pC1-A activation and in controls (see Key Resources Table for full genotypes). Data were analyzed and plotted as in (B). Dots above the dashed line represent persistent responses following activation.

Maximum Z-projection of the calcium response in a female expressing GCaMP6s in Dsx+ cells.

pC1 cells in the left hemisphere are shown. Calcium level ((F(t) -Fo/Fo), color coded) is shown 5 min before, 5 min during and 9.5 min after pC1-A activation (using csChrimson). The movie is sped up 20 times.

Last, using the same methodology, we examined neural activity in single Fru+ cells following pC1d/e activation, by expressing GCaMP6s via the Fru-LexA driver (Figure 8C, top). We found persistent activity in two group of cells, denoted as ‘Group 1’ and ‘Group 2’ (Figure 8C, bottom), that often lasted over a minute following activation (Figure 8D–E) – ROIs drawn manually for individual cells within each group. By comparing the location of Fru+ cell bodies with persistent activity with the position of single Fru+ cells and to the location of pC1/pC2/aIPg cells in FlyWire (Figure 8—figure supplement 2). We conclude that Group 2 includes pC1 neurons, while Group 1 likely includes pC2/pIP5 neurons and possibly also aIP-g cells. The persistent activity is most likely not in Dsx+/Fru+ pC2 neurons given our observations that Dsx+ pC2 cells do not show persistent activity following pC1d/e activation, but could be in pIP-e (also called pIP5 in the hemibrain). This is consistent with our analysis in FlyWire, showing that pIP5 is both pre- and post-synaptic to pC1d.

In sum, our pan-neuronal imaging reveals that female brain state is different at 0 and 3 min following activation, providing an explanation for the differences in behaviors produced following introduction of a male at these different delays. In addition, by clustering response types, we were able to map pC1d/e-driven persistent neural activity to brain regions containing both Dsx+ neurons and Fru+ aIPg neurons, and with follow-up experiments showed that several Dsx+ pC1 neurons as well as Fru+ putative pC1 and aIPg cells contain persistent neural activity. This is consistent with the recurrent circuit architecture we found using EM reconstruction (Figures 5–6).

Discussion

We find that pC1 neurons drive a persistent internal state in the Drosophila female brain that modulates multiple behaviors over timescales of minutes (receptivity, responses to male courtship song, aggressive behaviors, and male-like courtship behaviors [Figures 1–2 and 4]). The behavioral effects we observe may be similar to the effects of ‘emotion states’ observed in other animals, such as mice, fish, and primates (Anderson and Adolphs, 2014; Kunwar et al., 2015; Posner et al., 2005; Russell, 2003; Woods et al., 2014). In general, effects on behavior of such emotion states are thought to scale with levels of persistent neural activity (Hoopfer et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2014). We found that neural activity decays during a delay period following stimulation (Figures 7–8) and that behavioral effects of activation were also different following different delays. Specifically, we found that the highest levels of pC1 activation enhance receptivity but have an opposing effect on responses to male song (speeding females up instead of slowing them down). Slightly lower levels of pC1 activation (following a delay) bias females toward aggression and male-like behaviors. These effects on behavior may not naturally co-occur, but our optogenetic activation paradigm uncovers the scalable relationship between activation of different pC1 subtypes, their individual levels of activity, and distinct behavioral programs.

Our study also provides new insight into the neural mechanisms that contribute to changes in state on timescales of minutes (Figures 7–8). We used pan-neuronal imaging with registration to map responses that continue following pC1 optogenetic activation (previously, this technique had only been used to map sensory activity [Pacheco et al., 2021] and spontaneous activity [Mann et al., 2017]). We found that activation of pC1d/e neurons drives robust persistent neural activity throughout the posterior dorsal regions of the central brain (known to contain the processes of sexually dimorphic neurons [Cachero et al., 2010; Kimura et al., 2015], and overlapping with the Fru+ aIP-g neurons we identified as reciprocally connected with pC1d/e), lasting for minutes following activation. This is consistent with our behavioral observations - females still show elevated shoving and chasing even following a 6-min delay between optogenetic activation and the introduction of a male fly. Importantly, whether or not pC1 neurons themselves carry persistent neural activity has been debated (Inagaki et al., 2014; Jung et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2018). Here, we find that in females, Dsx+ pC1 neurons, as well as multiple Fru+ neurons, including putative pC1 and aIPg cells, do indeed carry persistent neural activity in response to our activation protocol (Figure 8).

pC1 neurons drive both aggression and receptivity in Drosophila females

We used unsupervised methods to identify the most prominent behaviors (beyond receptivity and responses to courtship song) produced following activation of pC1 neurons in virgin females - these include behaviors that resemble male courtship (female chasing the male) and aggression (female shoving the male) (Figure 2). Both behaviors are not typically observed in mature virgin females interacting with a male; this suggests that sensory cues from the virgin male do not inhibit these aberrant behaviors, but rather may enhance the persistent effects of pC1 activation (Figure 2F), most likely via visual inputs to aIPg neurons (Schretter et al., 2020). pC1 neurons also drive aggressive behaviors toward females during stimulation (Palavicino-Maggio et al., 2019; Schretter et al., 2020), but whether the quality of aggression generated toward males versus females is similar remains to be determined. As one of our manually scored behaviors, ‘female approaching’ (Figure 2—figure supplement 3A), begins from a distance greater than four body lengths from the male fly (a distance at which it may be difficult to discern male from female [Borst, 2009]) and often ends with shoving or circling (see Video 3), we hypothesize that pC1 activation most likely drives persistent behaviors toward another fly, and not specifically a male or female fly, consistent with (Schretter et al., 2020).

What is the role of female aggression? Female aggression, whether toward males or females, has been previously reported across model systems (Huhman et al., 2003; Stockley and Bro-Jørgensen, 2011; Woodley et al., 2000). In Drosophila, female-female fights over food source are strongly stimulated by the receipt of sperm at mating (Bath et al., 2017), and include both patterns that are common with male aggression (such as shoving and fencing) and female-only patterns (Nilsen et al., 2004). Female-male aggression was reported in the context of rejecting behavior in mated, immature, or older females (Cook and Connolly, 1973). The behavioral changes in our study do not mimic those in a mated female, as we also observe that pC1 activation drives enhanced receptivity. Although we have not confirmed which pC1 cell types control receptivity, our work reveals a separation: pC1d/e neurons are sufficient to drive persistent shoving/chasing, but do not have a persistent effect on female receptivity (Figure 4A–C), while separate pC1 neurons that control receptivity modulate the pathways that control chasing and aggression (Figure 4G–I). Recent work reveals that pC1a neurons are modulated by the sex peptide receptor pathway, such that following mating (when sex peptide is transferred), pC1a neurons are inhibited (Wang et al., 2020b). Because we find that pC1a provides direct input to pC1d and pC1e neurons (Figure 6A, Table 1; see also Schretter et al., 2020), we speculate that pC1a provides this receptivity information. Interestingly, work in male flies suggests a separation in pC1 subsets that control courtship versus aggression (Koganezawa et al., 2016), with reciprocal inhibitory influences between persistent courtship and aggression, following pC1 activation (Hoopfer et al., 2015). Although the phenotypes are sex-specific (male singing vs female receptivity; male tussling vs female shoving), and the pC1 subsets driving these behaviors are sex-specific (P1 in males, pC1d/e in females), this suggests some common architecture. Ultimately, comparing the connectomes of male and female brains, combined with functional studies, should elucidate both similarities and differences.

Because courtship interactions unfold over many minutes (Coen et al., 2014), we postulate that the changes in brain state we observed following pC1d/e activation may occur naturally as females receive continual drive to pC1 neurons. Our connectomic analyses reveal inputs to pC1d/e neurons from AVLP cells (Figure 6; Figure 6—figure supplement 1). The AVLP contains multiple auditory cells (Baker et al., 2020) - this is consistent with our patch clamp recordings of pC1d/e neurons (Figure 4—figure supplement 1), showing auditory activity, and also with prior work on auditory responses in female, but not in male pC1 neurons (Deutsch et al., 2019). Thus, during natural courtship interactions, male song should drive pC1d/e neurons – in combination with other inputs, this may shift behaviors from receptive ones toward chasing and shoving.

Recurrent circuitry and persistent neural activity

FlyWire enabled a systematic search for all the synaptic partners of a single pC1d and pC1e cell. Using manual and automatic synapse detection (Buhmann et al., 2019), we found that pC1d is reciprocally connected with aIPg-b and aIPg-c cells and that aIPg-b and aIPg-c cells are also interconnected – pC1e also shows reciprocal connectivity with aIPg-b neurons. We also identified pC1d and aIPg-c cells in a separate EM volume of an adult female brain, the hemibrain (Scheffer et al., 2020), and found similar results (see Schretter et al., 2020 for a thorough analysis of the pC1d connectome in the hemibrain). Because FlyWire is based on the FAFB dataset of the entire adult female brain (Zheng et al., 2018), our search for synaptic partners of pC1d and pC1e could completely cover both hemispheres, showing that, for example, pC1d is reciprocally connected to itself in the contralateral hemisphere, and is presynaptic to some contralateral aIPg cells. Comparisons between connectivity diagrams in the two female EM volumes of FAFB (segmented in FlyWire) and the hemibrain will continue to be of value for future studies.

Synaptically recurrent neural networks have been proposed to contribute to persistent neural activity lasting for seconds, and to underlie processes like accumulation of evidence and working memory (Aksay et al., 2007; Barak and Tsodyks, 2007; Major and Tank, 2004; Mante et al., 2013; Seung, 1996; Wang, 2008; Zylberberg and Strowbridge, 2017). For example, in Drosophila, recurrent excitatory loops in the ellipsoid body of the central complex contribute to stabilization of a heading navigation signal over timescales of seconds (Turner-Evans et al., 2020). Internal states underlying social behaviors, however, persist on much longer timescales of minutes to hours (Chen and Hong, 2018). Neuromodulation, via hormones or peptides, is thought to support longer timescales of persistence (Adolphs and Anderson, 2018; Bargmann, 2012; Marder, 2012; Zelikowsky et al., 2018). Our work now links a strongly recurrent neural network (pC1d/e to aIPg) to both minutes-long persistent neural activity and minutes-long changes in behavior. Work from Schretter et al., 2020 demonstrates that pC1d, pC1e, and aIPg neurons are all cholinergic, suggesting these neurons make up an excitatory neural network. While our study found persistent changes in behavior following pC1d/e activation, the Schretter et al., 2020 study did not – this discrepancy could arise from a number of methodological reasons, including differences in the optogenetic activator, timescale of activation, or in behavioral protocols. Nonetheless, Schretter et al., 2020 demonstrate that aIPg-b activation drives persistent female aggression following activation, and that increasing stimulation of aIPg-b, increases the amount of persistent aggression. This is consistent with a model in which strong activation of pC1d/e neurons recruits aIPg-b neurons (via their excitatory interconnections) to drive, at least, persistent shoving.

Work in male flies has proposed a recurrent circuit motif including pCd neurons that contributes to persistent aggressive behaviors (Jung et al., 2020) or even longer term changes in mating drive (driven by male-specific P1 neurons, but without mapping the synaptic connections). Our studies of pCd, revealed that, in females, it does not contribute to the persistent arousal state (Figure 2—figure supplement 2), nor is it persistently active following pC1d/e activation (Figure 8—figure supplement 1). In males, activating P1 neurons for 5 s was enough to induce some persistent activity in pCd cells (Jung et al., 2020). We did not measure neural responses to pC1d/e stimulation shorter than 2 min, and so whether shorter activation periods drive some persistent neural activity in females remains open. While pC1d/e neurons are female-specific, aIPg neurons are present in both males and females – it will be interesting to determine what role the aIPg neurons play in male brains and whether they represent a shared component of persistence in the two sexes.

Finally, it is important to point out that recent EM connectomic work in Drosophila using FAFB (via manual tracing) has revealed a number of recurrent or reciprocal circuits throughout the brain (Dolan et al., 2018, Sayin et al., 2019; Turner-Evans et al., 2020). Half of the outputs of pC1d are the aIPg neurons, and many of these neurons (several aIPg-b and aIPg-c cells) are strong inputs. Our identification of a recurrent circuit motif containing pC1d links it to the persistent neural activity and changes in behavior we observe following activation, especially in Fru+ somas. This is an important first step toward determining how recurrent neural networks contribute to such long timescales of persistence.

Materials and methods

| Reagent type (species) or resource | Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | NM91 | Coen et al., 2014 | A gift from Peter Andolfatto | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | Dsx-Gal4 (III) | Rideout et al., 2010 | A gift from Stephen Goodwin | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | Dsx-LexA::P65 (III) | Zhou et al., 2015 | A gift from Bruce Baker | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | UAS-2xEGFP (II) | BDSC: 6874; RRID:BDSC_6874 | ||

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | R71G01-LexA (II) | Pan et al., 2012 | BDSC: 54733; RRID:BDSC_54733 | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | R41A01-LexA (II) | Zhou et al., 2014 | BDSC: 54787; RRID:BDSC_54787 | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | 8xLexAop2-FLP (II) | BDSC: 55820; RRID:BDSC_55820 | ||

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | UAS > STOP > TNT (III) | Stockinger et al., 2005 | A gift from Barry Dickson | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | UAS-ReachR (III) | Inagaki et al., 2014 | BDSC: 53749; RRID:BDSC_53749 | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | VT25602.p65ADZp (II) | Wu et al., 2019 | A gift from Barry Dickson | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | VT2064.ZpGAL4DBD (III) | Wu et al., 2019 | A gift from Barry Dickson | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | UAS(FRT.mCherry) ReachR (III) | Inagaki et al., 2014 | BDSC: 53740; RRID:BDSC_53740 | A gift from David Anderson |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | R71G01-p65.AD (II) | Dionne et al., 2018 | BDSC: 70798; RRID:BDSC_70798 | A gift from Gerry Rubin |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | Dsx.DBD (III) | Pavlou et al., 2016 | A gift from Stephen Goodwin | |

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | 10xUAS-IVS-myr::GFP (II) | BDSC: 32198; RRID:BDSC_32198 | ||

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | W+,NorpA (X) | BDSC: 9048; RRID:BDSC_9048 | ||

| Genetic reagent (D. melanogaster) | VT25602-Gal4 (III) | A gift from Barry Dickson | ||