Assessment of neurovascular coupling and cortical spreading depression in mixed mouse models of atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease

Figures

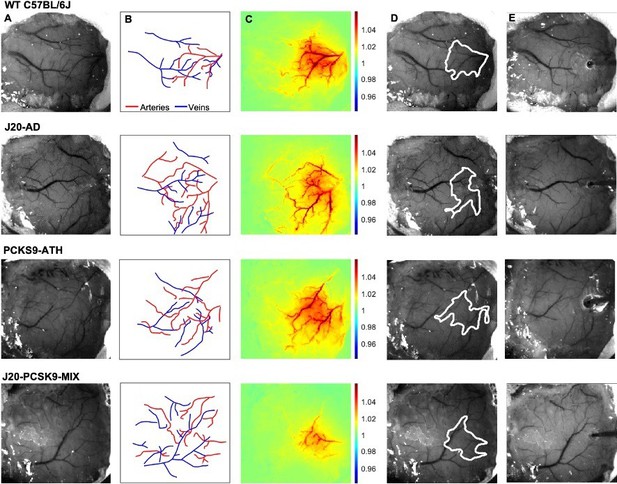

Experimental setup and data derivation.

(A) Raw image of representative thinned cranial windows for WT, J20-AD, PCKS9-ATH AND J20-PCSK9-MIX mice (chronic imaging session). (B) Vessel map outlining the major arteries and veins within the thinned cranial window. (C) HbT spatial activation map showing fractional changes in HbT in response to a 16s-whisker stimulation. (D) Automated computer-generated region of interest (ROI) determined from the HbT activation response in C from which time-series for HbT, HbO, and HbR are generated. (E) Raw image of the same animals in terminal acute imaging sessions with multichannel electrodes inserted into the active ROI determined from chronic imaging session.

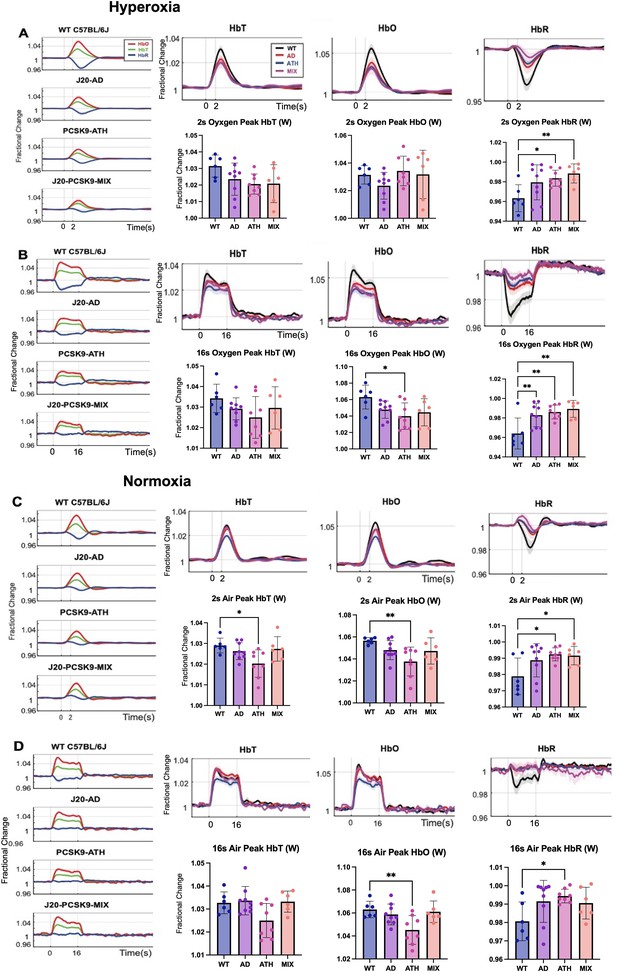

Fractional changes in chronic stimulus-evoked haemodynamic responses (Peak/Mean; Whisker Region).

(A) 2s-stimulation in which all animals were breathing in 100% oxygen (hyperoxia). (B) 16-stimulation (hyperoxia). (C) 2s-stimulation in which all animals were breathing in 21% oxygen (normoxia). (D) 16s-stimulation (normoxia). All animals aged 9–12 m: WT (n = 6), J20-AD (n = 9), PCSK9-ATH (n = 8), J20-PCSK9-MIX (n = 6). (HbT:) There was no significant overall effect of disease F(3,25)=2.83, p = 0.059. However, Dunnett’s (two-sided) multiple comparisons test revealed there was a significant difference between WT and ATH (p = 0.023). As expected, there was a significant effect of experiment, F(1.65,41.14) = 13.64, p < 0.001. There was also no significant interaction effect between experiment and disease, F(4.94,41.14) = 1.50, p = 0.211. (HbO): There was a significant overall effect of disease F(3,25)=4.84, p = 0.009. Dunnett’s (two-sided) multiple comparisons test revealed there was a significant difference between WT and ATH (p = 0.002). There was a significant effect of experiment, F(1.47,36.72) = 15.348, p < 0.001. There was no significant interaction effect between experiment and disease, F(4.41,36.72) = 1.64, p = 0.181. (HbR): There was a significant overall effect of disease F(3,25)=4.86, p = 0.008. Games-Howell multiple comparisons reveal HbR peak is significantly different for WT vs ATH (p = 0.040). There was a significant effect of experiment, F(1.69,42.28) = 17.33, p < 0.001. There was a significant interaction between experiment and disease interaction: F(5.07, 42.28) = 3.19, p = 0.015. All error bars (lightly shaded) are± SEM. Vertical dotted lines indicate start and end of stimulations. Bar graphs compare whisker region evoked HbT, HbO, and HbR within each group to WT mice for each experimental condition. Dots indicate individual animals. One-way ANOVA was performed with post-hoc Dunnett’s test to determine significance within each condition denoted as p > 0.05 as * and p > 0.01 as ** (Error bars ± SD).

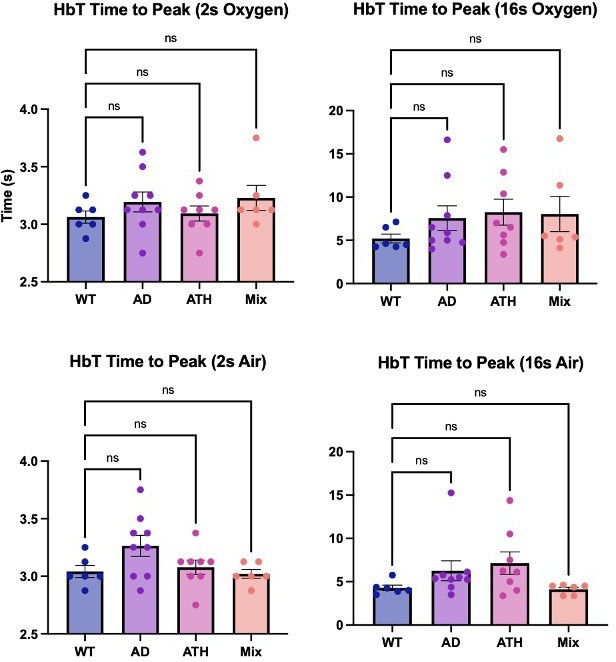

Time to peak (chronic).

Bar graphs showing the average time (s) to reach the peak HbT response across the different experimental groups. There is no significant difference across any of the disease groups or experimental conditions. Dots represent individual animals. Error bars ± SD.

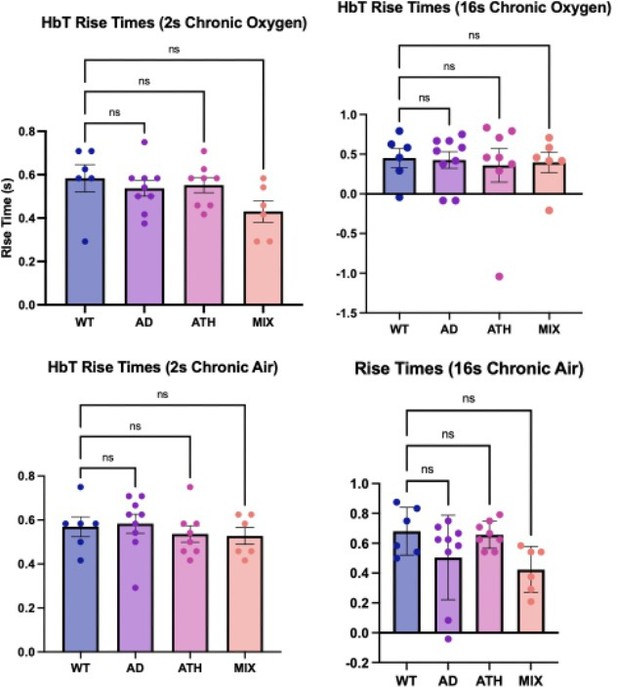

Rise times (chronic).

Bar graphs showing the average rise times for HbT across the different experimental groups. There is no significant difference across any of the disease groups or experimental conditions. Dots represent individual animals. Error bars ± SD.

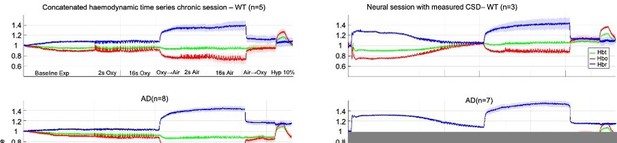

Concatenated data showing stability and robustness of the mouse imaging preparation.

(Left) Chronic imaging sessions including a 35min haemodynamics baseline before first stimulation. (Right) Acute imaging sessions including CSD plus 35-min haemodynamics recovery before first stimulation.

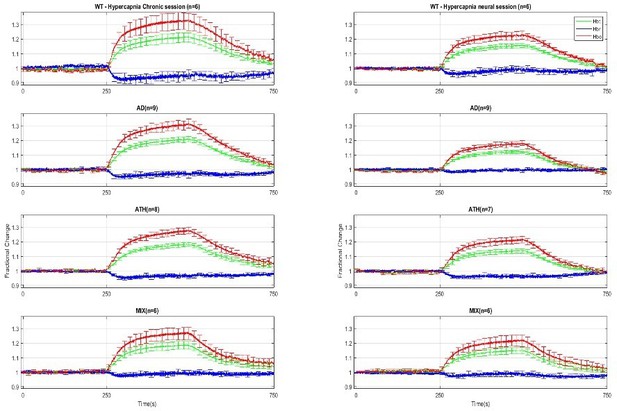

Chronic (left) and acute (right) hypercapnia.

Chronic Mean: A Kruskal-Wallis test showed no significant effect of disease for HBT (H(3)=3.937, p = 0.268), HbO (H(3)=3.866, p = 0.276), nor HbR (H(3)=3.742, p = 0.291). Acute Mean: A one-way ANOVA showed no significant effect of disease for HbT F(3,24)=0.775, p = 0.519, HbO F(3,24)=0.748, p = 0.534, HbR F(3,10.933) = 2.695, p = 0.098. Error bars ± SEM. Arterial region data and AUC data were not significant in either chronic or acute hypercapnia (Table 1).

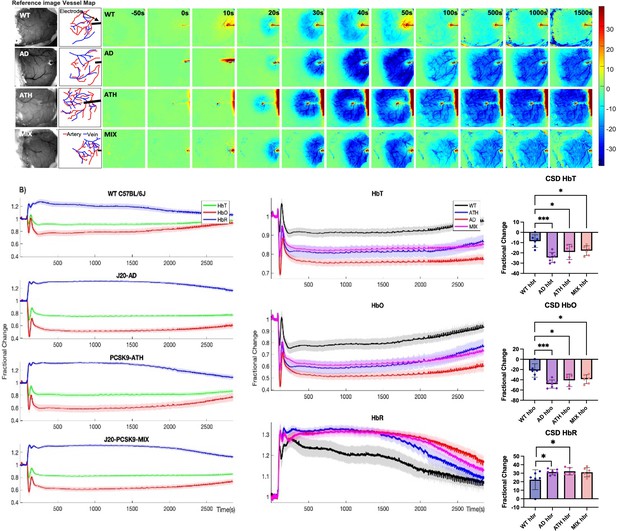

Cortical spreading depression (CSD) in WT, diseased and comorbid animals.

(A) Representative montage time-series of WT, J20-AD, PCSK9-ATH and J20-PCSK9-MIX mice showing HbT changes post-electrode insertion. Electrode insertion occurs at t = 0 s. Colour bar represents percentage changes in HbT from baseline. (B) Left: Average CSD haemodynamics profiles for control animals (WT C57BL/6 J and nNOS-ChR2) (n = 7); mean HbT (625–1250 s) C57BL/6 J (n = 3): 0.9031 ± 0.028598 STD, mean HbT nNOS-ChR2 (n = 4): 0.92355 ± 0.063491 STD (p = 0.64816; ns), J20-AD (n = 7), PCSK9-ATH (n = 5) and J20-PCSK9-MIX (n = 6) mice. Right: Averaged changes to HbT (top), HbO (middle) and HbR (bottom) upon CSD in the different mouse groups. (HbT:) A one-way ANOVA showed significant effect of disease for HbT (F(3,21)=9.62, p < 0.001). Dunnett’s two-sided multiple comparisons showed that AD vs WT p < 0.001, ATH vs WT p = 0.012 & MIX vs WT p = 0.020. (HbO:) one-way ANOVA showed significant effect of disease for HbO (F(3,21)=8.51, p = 0.001). Dunnett’s two-sided multiple comparisons showed that AD vs WT p < 0.001, ATH vs WT p = 0.01 and MIX vs WT p = 0.017. (HbR:) one-way ANOVA showed significant effect of disease for HbR (F(3,21)=3.60, p = 0.031). Dunnett’s two-sided multiple comparisons showed that AD vs WT p = 0.037, ATH vs WT p = 0.038, MIX vs WT p = 0.053. All error bars (lightly shaded) are± SEM. Bar graphs illustrate HbT, HbO, and HbR fractional changes between 625 and 1250 s with one-way ANOVA showing significant effect of disease for all parameters. Post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparisons are denoted by asterixis. Error bars ± SD.

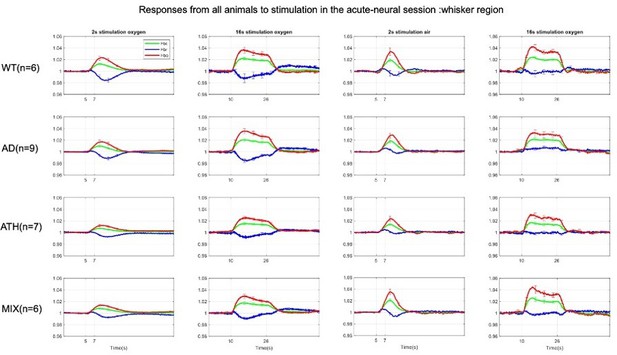

Fractional changes in acute stimulus-evoked haemodynamic responses.

HbT: There was no significant overall effect of disease F(3,24)=1.69, p = 0.196. As expected, there was a significant effect of experiment, F(2.16,51.73) = 76.72, p < 0.001. There was no significant interaction effect between experiment and disease, F(6.47,51.73) = 1.73, p = 0.127. (HbO:) There was no significant overall effect of disease F(3,24)=1.36, p = 0.280. There was a significant effect of experiment, F(2.02,48.57 = 62.10, p < 0.001). There was no significant interaction effect between experiment and disease, F(6.07,48.57) = 2.08, p = 0.072. (HbR:) There was no significant overall effect of disease F(3,24)=1.42, p = 0.262. As expected, there was a significant effect of experiment, F(2.18,52.42) = 17.54, p < 0.001. There was a significant interaction effect between experiment and disease F(6.55, 52.42) = 2.54, p = 0.028. All error bars (lightly shaded) are± SEM. Vertical dotted lines indicate start and end of stimulations.

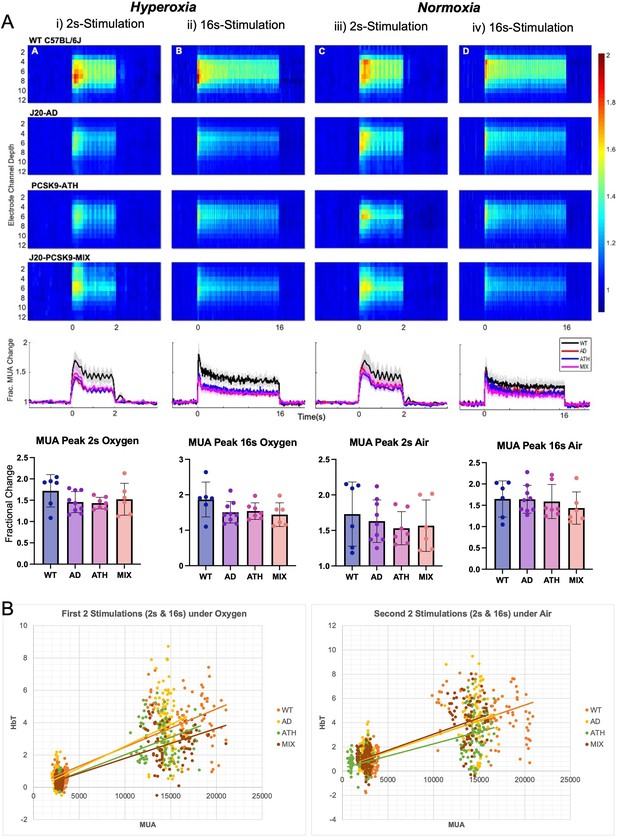

Evoked neural multi-unit activity (MUA) responses.

(A) MUA heat maps showing fractional changes in MUA along the depth of the cortex (channels 4–8) in response to stimulations in WT C57BL/6 J (n = 6), J20-AD (n = 9), PCSK9-ATH (n = 7) and J20-PCSK9-MIX (n = 6) mice. Overall effect of disease on MUA F(3,24)=2.24, p = 0.109 (2-way mixed design ANOVA). There was a significant effect of experiment, as expected, F(2.26, 54.16) = 6.83, p = 0.002. There was no significant interaction between experiment and disease F(6.77, 54.16) = 0.70, p = 0.670. All error bars (lightly shaded) are± SEM. Bar graphs showing fractional changes in peak MUA for each group in each experimental condition with one-way ANOVA showing no significant differences in MUA between groups for any experiment. Error bars ± SD. (B) Neurovascular correlation plots of trial-by-trial data (not individual animal means) comparing evoked MUA (peak) against subsequent evoked HbT (peak) changes. The two plots are time related with the left being the first two set of stimulations after electrode insertion/CSD in which animals were breathing in 100% oxygen (hyperoxia) and the right being the second set of stimulations occurring later in the experimental paradigm in which all animals were breathing in air (21% oxygen; normoxia). The 2s-stimulations are the smaller cluster to the left of each plot whereas the 16s-stimulations are the larger cluster to the right of each plot. Line equations and R-values (regression analysis). Oxygen (Hyperoxia). WT: y = 0.0002x + 0.1194, R² = 0.6867. AD: y = 0.0003 x-0.1467, R² = 0.6693. ATH: y = 0.0002 x-0.1446, R² = 0.6936. MIX: y = 0.0002 x-0.0659, R² = 0.7044. Air (Normoxia). WT: y = 0.0003x + 0.3501, R² = 0.5736. AD: y = 0.0003x + 0.3502, R² = 0.5066. ATH: y = 0.0002x + 0.251, R² = 0.4898. MIX: y = 0.0003x + 0.3739, R² = 0.5996.

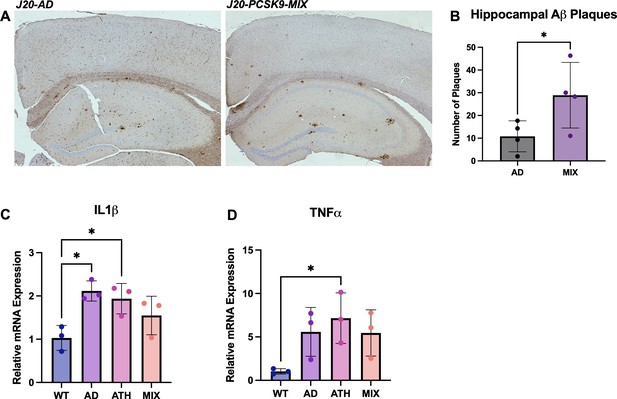

Neuropathology and Neuroinflammation.

(A) Representative histological coronal hippocampal sections for J20-AD and J20-PCSK9-MIX mice stained with anti-Aβ to visualise Aβ plaques. (B) Increased number of amyloid-beta plaques in the hippocampus of J20-PCSK9-MIX mice compared to J20-AD mice (p = 0.036; unpaired t-test) (n = 4 each). Cortical plaques p = 0.3372 (data not shown). (D) qRT-PCR for 1L1β: AD vs WT p = 0.011, ATH vs WT p = 0.0278, MIX vs WT p = 0.218 (one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test). (E) qRT-PCR for TNFα: AD vs WT p = 0.1197, ATH vs WT p = 0.0370, MIX vs WT p = 0.1313 with post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. All error bars are± SD.

Tables

Summary of statistics.

| Metric | Statistical test | p-Values and summary |

|---|---|---|

| Neural multi-unit activity | Two-way ANOVA post hoc Dunnett’s | Not significant for any model. Peak: F(3,24)=2.24, p = 0.109 not significant AUC: F(3,24)=1.66, p = 0.114 not significant |

| Peak arterial region chronic haemodynamics | Two-way ANOVA post hoc Dunnett’s | HbT WT vs ATH p = 0.026(*). No other metric is significant for peak arterial data across all stimulations/conditions. |

| Chronic hypercapnia | One-way ANOVA post hoc Dunnett’s Kruskal Wallis (AUC) | Not significant for any model. Mean HbT F(3,12.06) = 0.49, p = 0.694 Arterial mean HbT F = 0.692, p = 0.566 AUC HbT H(3)=4.011, p = 0.26 |

| Acute hypercapnia | One-way ANOVA post hoc Dunnett’s Kruskal Wallis (Mean Arterial HbT) | Not significant for any model. Mean HbT F(3,24)=0.775, p = 0.519 AUC HbT F(3,24)=0.78, p = 0.519 Arterial mean HbT H(3)=3.6, p = 0.308 |

| Amyloid-beta staining | Unpaired T-tests | Hippocampal: p = 0.036(*) Cortical: p = 0.337(ns) Whole Brain: p = 0.0328(*) |