Emotional vocalizations alter behaviors and neurochemical release into the amygdala

Figures

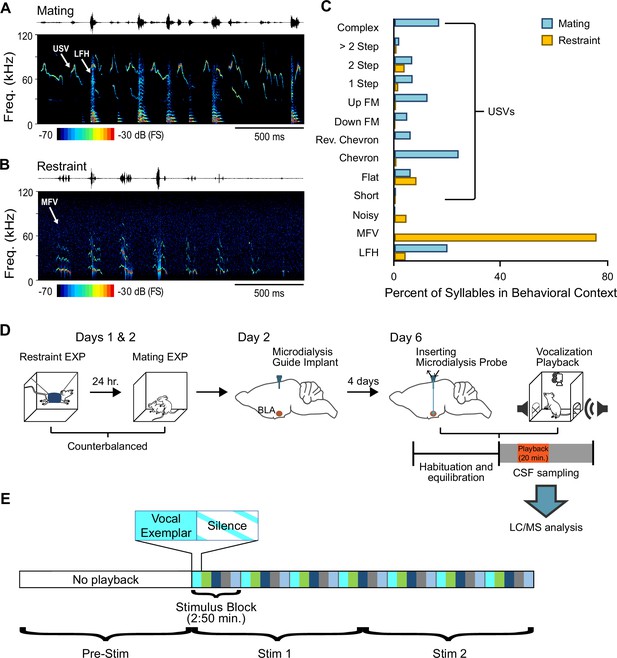

Behavioral/microdialysis experiments test how playback of affective vocal signals alters behaviors and neuromodulator release into the basolateral amygdala (BLA).

(A) Short sample of mating vocal sequence used in playback experiments. Recording was obtained during high-intensity mating interactions and included ultrasonic vocalizations (USVs), likely emitted by the male, as well as low-frequency harmonic (LFH) calls likely emitted by the female. (B) Short sample of restraint vocal sequence used in playback experiments. Recording was obtained from an isolated, restrained mouse (see Material and methods) and consisted mostly of mid-frequency vocalization (MFV) syllables. (C) Syllable types in mating playback sequences differ substantially from those in restraint playback sequences. Percentages indicate frequency-of-occurrence of syllable types across all examplars used in mating or restraint vocal stimuli (nMating = 545, nRestraint = 622 syllables). See also Figure 1—source data 1. (D) Experimental design in playback experiment. Days 1 and 2: each animal experienced restraint and mating behaviors (counterbalanced order across subjects). Day 2: a microdialysis guide tube was implanted in the brain above the BLA. Day 6: the microdialysis probe was inserted through guide tube into the BLA. Playback experiments began after several hours of habituation/equilibration. Behavioral observations and microdialysis sampling were obtained before, during, and after playback of one vocalization type. Microdialysis samples were analyzed using liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS) method described in Materials and methods. (E) Schematic illustration of detailed sequencing of vocal stimuli, shown here for mating playback. A 20-min period of vocal playback was formed by seven repeated stimulus blocks of 170 s. The stimulus blocks were composed of five vocal exemplars (each represented by a different color) of variable length, with each exemplar followed by an equal duration of silence. Stimuli during the Stim 1 and Stim 2 playback windows thus included identical blocks but in slightly altered patterns. See Material and methods for in-depth description of vocalization playback.

-

Figure 1—source data 1

This source data file identifies each syllable occurrence throughout the vocal examplars used in mating and restraint playback and summarized in Figure 1C.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/88838/elife-88838-fig1-data1-v1.xlsx

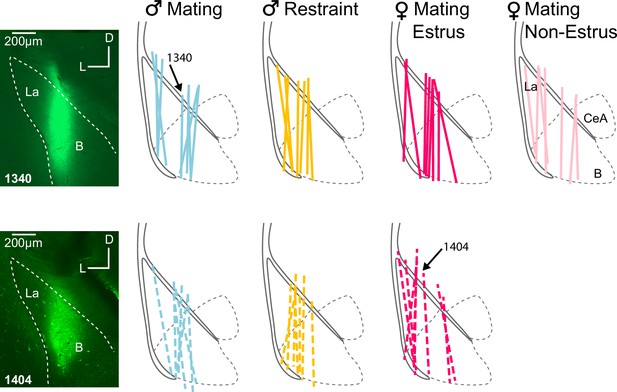

Microdialysis probe locations for EXP and INEXP groups.

Labels above basolateral amygdala (BLA) outlines indicate groups based on playback type, sex, and hormonal state. Colored lines indicate recovered probe tracks that resulted from infusion of fluorescent tracers. Black solid lines indicate external capsule; black dashed lines indicate major amygdalar subdivisions. Arrows indicate tracks related to insets. Insets: photomicrographs show dextran-fluorescein labeling that marks the placement of the microdialysis probes for two cases, 1340 and 1404. Abbreviations: B, basal nucleus of amygdala; CeA, central nucleus of amygdala; La, lateral nucleus of amygdala.

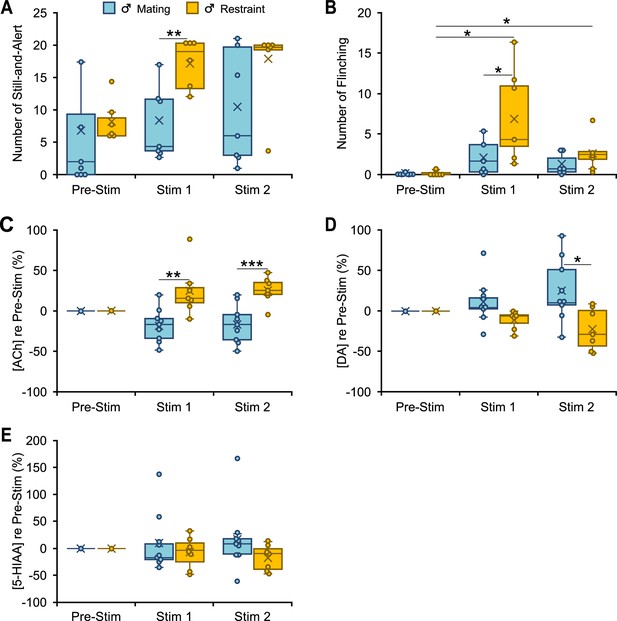

Behavioral and neuromodulator responses to vocal playback in male mice differ by behavioral context of vocalizations.

(A, B) Boxplots show number of occurrences of specified behavior in 10-min observation periods before (Pre-Stim) and during (Stim 1, Stim 2) playback of mating or restraint vocal sequences (nMating = 7, nRestraint = 6). Note that playback sequences during Stim 1 and Stim 2 periods were identical within each group. During playback, the restraint group increased still-and-alert behavior compared to the mating group (A) (context: F(1,11) = 9.6, p = 0.01, ŋ2 = 0.5), and increased flinching behavior (B) (time*context: F(1.1,12.2) = 6.3, p = 0.02, ŋ2 = 0.4) compared to the Pre-Stim baseline and to the mating group. (C–E) Boxplots show differential release of acetylcholine (ACh), dopamine (DA), and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) relative to the Pre-Stim period, during mating and restraint vocal playback (nMating = 9, nRestraint = 7). (C) Significant differences in ACh for restraint (increase) playback in Stim 1 and Stim 2 vs males in mating playback (Main effect of context: F(1,14) = 22.6, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.62). (D) Significant differences for DA for mating (increase) vs restraint playback (Main effect of context: F(1,14) = 7.4, p = 0.02, ŋ2 = 0.35). (E) No significant changes in 5-HIAA during vocal playback in male mice (context: F(1,14) = 1.36, p = 0.3, ŋ2 = 0.09). (A–E) Statistical testing examined time windows within groups for behavioral observations and all intergroup comparisons within time windows for both behavior and neuromodulator data. Only normalized neuromodulators in Stim 1 and Stim 2 were used for statistical comparisons. Only significant tests are shown. Repeated measures generalized linear model (GLM): *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (Bonferroni post hoc test). Time windows comparison: 95% confidence intervals. See Data analysis section in Materials and methods for description of box plots. See Figure 3—source data 1–4 for all numerical data for Figures 3—6.

-

Figure 3—source data 1

This source data file shows the raw and normalized values of acetylcholine (ACh) concentration for each measurement displayed in Figures 3—6.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/88838/elife-88838-fig3-data1-v1.xlsx

-

Figure 3—source data 2

This source data file shows the raw and normalized values of dopamine (DA) concentration for each measurement displayed in Figures 3—6.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/88838/elife-88838-fig3-data2-v1.xlsx

-

Figure 3—source data 3

This source data file shows the raw and normalized values of 5-HIAA concentration for each measurement displayed in Figures 3, 4 and 6.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/88838/elife-88838-fig3-data3-v1.xlsx

-

Figure 3—source data 4

This source data file shows the values for behavioral events and tracking data for each measurement displayed in Figures 3—5.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/88838/elife-88838-fig3-data4-v1.xlsx

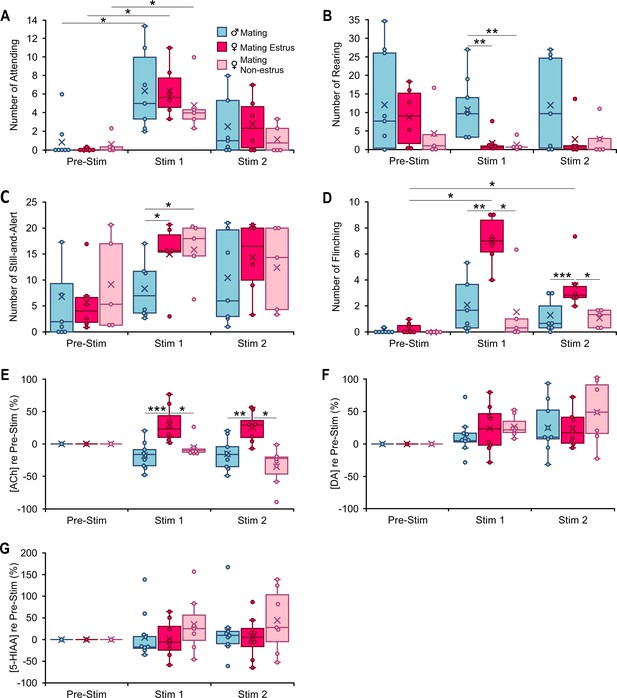

Behavioral and neuromodulator responses to playback of mating vocal sequences differ by sex and female estrous stage.

(A–D). Occurrences of specified behaviors in 10-min periods before (Pre-Stim) and during (Stim 1, Stim 2) mating vocal playback (nMale = 7, nEstrus Fem = 6, nNon-estrus Fem = 5). (A) Attending behavior increased during Stim 1 in response to mating vocal playback, regardless of sex or estrous stage (time: F(2,30) = 32.6, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.7; time*sex: F(2,30) = 0.12; p = 0.9, ŋ2 = 0.008; time*estrous: F(2,30) = 1.1; p = 0.4, ŋ2 = 0.07). (B, C) Females regardless of estrous stage reared less (sex: F(1,15) = 10.22, p = 0.006; ŋ2 = 0.4; estrous: F(1,15) = 0.2, p = 0.7, ŋ2 = 0.01) and displayed more Still-and-Alert behaviors (sex: F(1,15) = 5.2, p = 0.04, partial ŋ2 = 0.3, estrous: F(1,15) = 0.07, p = 0.8, partial ŋ2 = 0.005) than males during mating vocal playback. (D) Estrus females, but not non-estrus females or males, showed a significant increase in flinching behavior during Stim 1 and Stim 2 periods (time*estrous: F(2,30) = 9.0, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.4). (E–G) Changes in concentration of acetylcholine (ACh), dopamine (DA), and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) relative to the Pre-Stim period, evoked during Stim 1 and Stim 2 periods of vocal playback (nMale = 9, nEstrus Fem = 8, nNon-estrus Fem = 7). (E) Release of ACh during mating playback increased in estrus females (Stim 1, Stim 2) but decreased in males and non-estrus females (Stim 2). Among groups, there was a significant estrous effect (estrous: F(1,21) = 29.0, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.0.6). (F) DA release during mating playback increased in all groups relative to Pre-Stim period, with no significant sex (F(1,21) = 0.8, p = 0.4, ŋ2 = 0.04) or estrous effect (F(1,21) = 0.9, p = 0.4, ŋ2 = 0.04). (G) No significant changes in 5-HIAA during mating sequence playback (sex: F(1,21) = 0.07, p = 0.8, ŋ2 = 0.004; estrus: F(1,21) = 1.6, p = 0.22, ŋ2 = 0.07). (A–G) Repeated measures generalized linear model (GLM): *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (Bonferroni post hoc test). Time windows comparison: 95% confidence intervals.

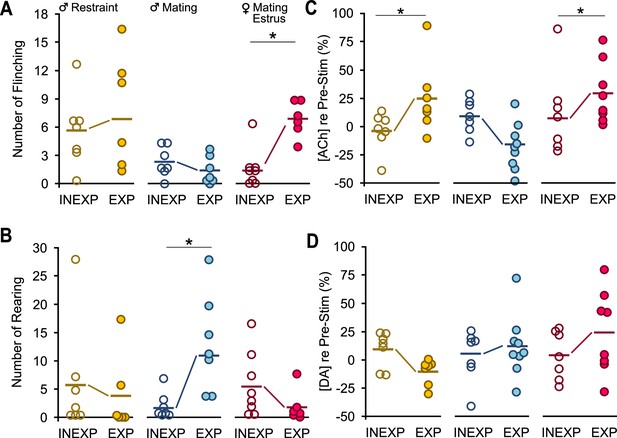

A single bout each of mating and restraint experience altered behaviors and acetylcholine (ACh) release in response to vocal playback.

In all graphs, dots represent measures from individual animals obtained during the Stim 1 playback period; thick horizontal lines represent mean values across subjects. There were no differences in behavioral counts for Pre-Stim values between INEXP and EXP mice for any group (e.g., male-restraint, male-mating, estrus female-mating). Neuromodulator values are normalized to the baseline level. (A) Experience increased flinching responses in estrus female mice but not in males in mating or restraint vocal playback (time*sex*experience: F(1.6,56) = 4.1, p = 0.03, ŋ2 = 0.11). (B) Experience increased rearing responses in males exposed to mating playback (sex*experience: F(1,35) = 5.3, p = 0.03, ŋ2 = 0.13). (C) Estrus female mice (sex*experience: F(1,39) = 8.0, p = 0.008, ŋ2 = 0.2) and restraint male mice (context*experience = F(1,39) = 13.0, p < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.2) displayed consistent experience effect for changes in ACh. (D) Dopamine (DA) did not show the EXP effect observed in ACh during vocal playback (sex*experience: F(1,39) = 0.12, p = 0.7, ŋ2 = 0.003; context*experience: F(1,39) = 4.0, p = 0.052, ŋ2 = 0.09). Generalized linear model (GLM) repeated measures with Bonferroni post hoc test: *p < 0.05.

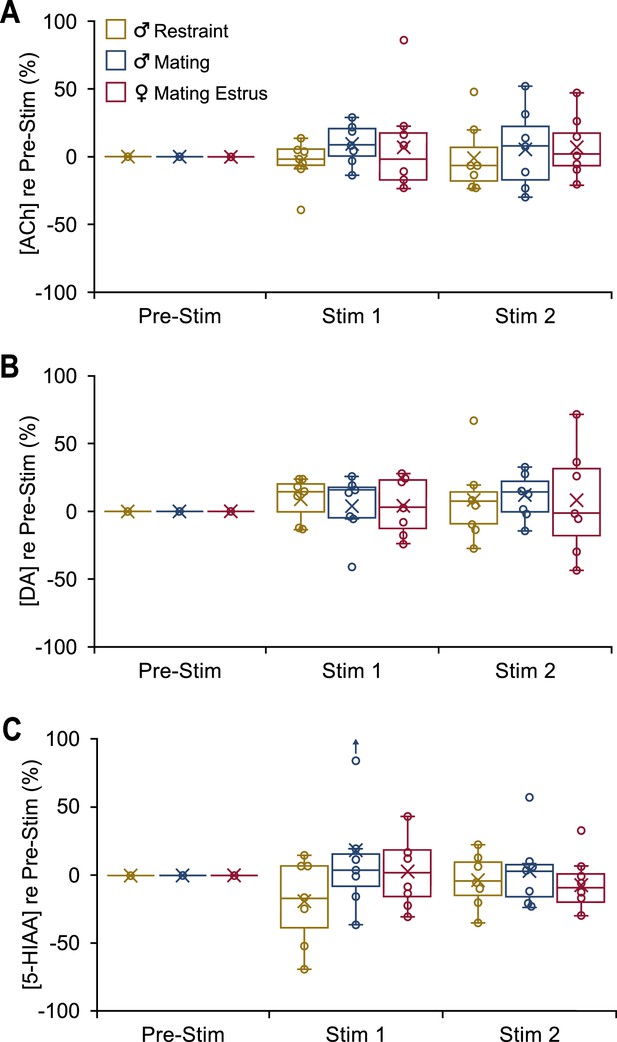

In INEXP mice, vocal playback failed to evoke distinct patterns in neuromodulator release.

Boxplots show change in concentration of the specified neuromodulator in 10-min playback periods (Stim 1, Stim 2) compared to the baseline level (Pre-Stim). Male-restraint, nINEXP = 7; male-mating, nINEXP = 7; estrus female-mating, nINEXP = 7. (A) Acetylcholine (ACh) release shown for both playback periods. (B) Dopamine (DA) release shown for both playback periods. (C) 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) concentration shown for both playback periods.

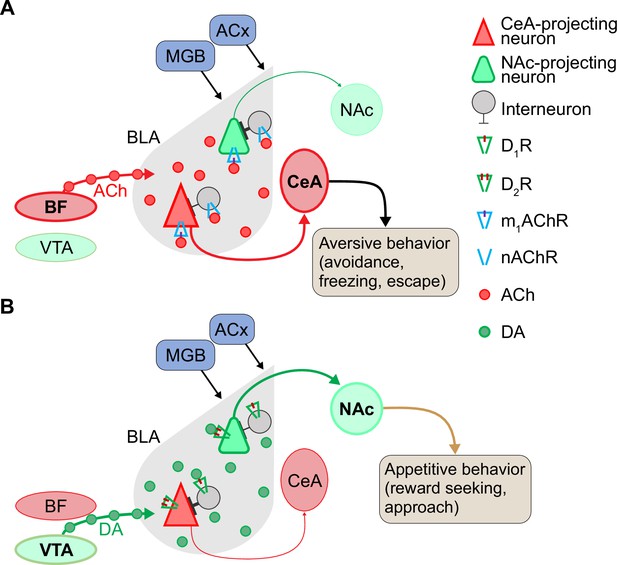

Proposed model for neuromodulation of salient vocalization processing via acetylcholine (ACh) and dopamine (DA) in the basolateral amygdala (BLA).

(A) Cholinergic modulation of CeA-projecting neurons during aversive vocalization cue processing in the BLA. In the presence of aversive cues, ACh released from the basal forebrain acts on M1 ACh receptors (M1 mAChRs) to enhance the cue-induced excitatory responses of CeA-projecting neurons. In contrast, NAc-projecting neurons are quiescent, because they do not respond to aversive cues and are inhibited by interneurons that are activated through nicotinic ACh receptors (nAChRs). (B) Dopaminergic modulation and enhancement of signal-to-noise ratio in response to reward-associated cues (appetitive vocalizations). When vocalizations or other rewarding cues are present, release of DA from VTA enhances D2R-mediated excitation in NAc-projecting neurons that are responsive to positive cues. In contrast, CeA-projecting neurons are not responsive to rewarding vocalizations and are inhibited by local interneurons. DA is thought to act on D1 DA receptors (D1Rs) in these local interneurons to shape a direct inhibition onto CeA-projecting neurons. Abbreviations: ACx, auditory cortex; BF, basal forebrain; CeA, central nucleus of amygdala; MGB, medial geniculate body; NAc, nucleus accumbens; VTA, ventral tegmental area.

Tables

Classification of manually evaluated behaviors during playback of vocalizations.

| Behavior | Definition |

|---|---|

| Abrupt attending | Sudden and quick pause in locomotion followed by abrupt change in head and body position lasting 2+ s. This behavior is accompanied by fixation of the eyes and ears during attending. Appears similar to ‘freezing’ behavior described in fear conditioning but occurs in the context of natural response to vocalizations. |

| Flinch | A short-duration twitch-like movement in response to vocal sequences, occurring at any location within arena. Unlike acoustic startle (Grimsley et al., 2015), this behavior occurs in free-moving animals in response to non-repetitive, variable-level vocal stimuli. Flinching movements are of smaller magnitude than those observed in acoustic startle. |

| Locomotion | Movement of all four limbs from one quadrant of the arena to another. |

| Rearing | A search behavior during which the body is upright and the head is elevated to investigate more distant locations. |

| Self-grooming | Licking fur and using forepaws to scratch and clean fur on head. The behavior can extend to other parts of the body. |

| Still-and-alert | Gradual reduction or lack of movement for 2+ s, during which animal appears to be listening or responding to external stimulus. Distinguished from abrupt attending by gradual onset. |

| Stretch-attend posture | A risk-assessment behavior during which hind limbs are fixed while the head, forelimbs, and the body are stretched sequentially in different directions. |