Goal-directed vocal planning in a songbird

Figures

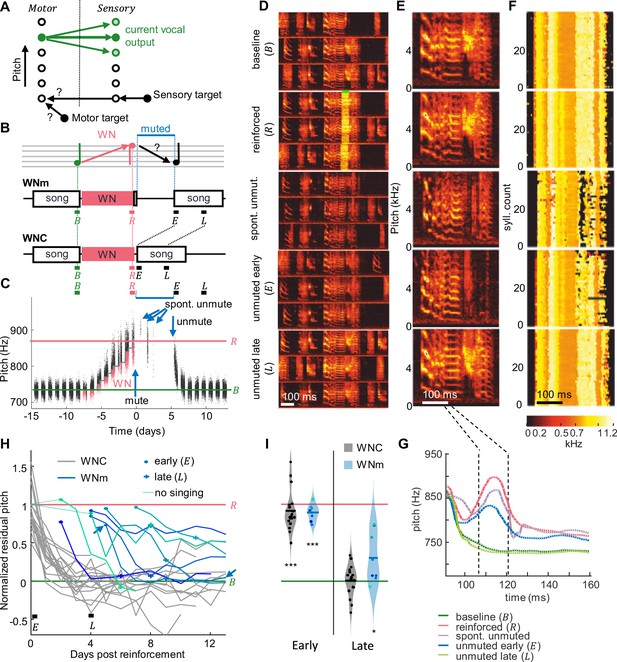

Recovery of pitch target requires practice.

(A) Two hypotheses on birds’ ability to recover a song target away from their current vocal output (green circles, motor states on the left, sensory states on the right, shading represents probabilities): Either they could recall the motor target and reactivate it without practice or they could recall a sensory target plus the neural mapping (black arrows) required to transform it into a motor state. (B) WNm birds were first pitch-reinforced using white noise (WN), then muted, and subsequently unmuted. WN was delivered when the pitch of the target syllable was either below (as exemplified here) or above a threshold. Pitch recovery from the reinforced () state toward the baseline () target is evaluated in early ( no practice) and late (, with practice) analysis windows (all windows are time-aligned to the first 2 hr of songs after withdrawal of reinforcement, ) and compared to recovery in unmuted control birds (WNC). (C) Syllable pitches (dots, red = reinforced syllables) of an example bird that while muted recovered only about 27% of pitch difference to baseline despite three spontaneous unmuting events (arrows). (D) Same bird, spectrograms of example song motifs from five epochs: during baseline (), reinforcement () with WN (green bar), spontaneous unmuting (spont. unmut.), and during permanent unmuting (early – and late – ). (E) Example syllables from same five epochs. (F) Stack plot of pitch traces (pitch indicated by color, see color scale) of the first 40 targeted syllables in each epoch (‘reinforced’: only traces without WN are shown). (G) Average pitch traces from (F), revealing a pitch increase during the pitch-measurement window (dashed black lines) and pitch recovery late after unmuting. (H) WNm birds (blue lines, N = 8) showed a normalized residual pitch (NRP) far from zero several days after reinforcement (circles indicate unmuting events, arrow shows bird from C) unlike WNC birds (gray lines, N = 18). Thin dashed lines indicate the two initial birds that were not given reinforcement-free singing experience before muting (see ‘Materials and methods’). (I) Violin plots of same data restricted to early and late analysis windows (***p<0.001, *p<0.05, two-tailed t-test of NRP = 0).

Birds rapidly recover pitch but not duration after reinforcement learning.

(A) Birds were pitch or duration reinforced using white noise (WN). Pitch recovery from the reinforced () state toward the baseline () target is evaluated in an early (, no practice) analysis window and a late () window 4 days later. (B) After ending WN reinforcement on day 0, pitch (gray lines, N = 19 experiments from 18 birds) recovered their normalized residual pitch (NRP)/normalized residual duration (NRD) faster and more fully than duration (blue lines, N = 14 experiments from 13 birds). (C) Violin plots of same data restricted to early and late analysis windows (***p<0.001, **p<0.01, two-tailed t-test of NRP = 0).

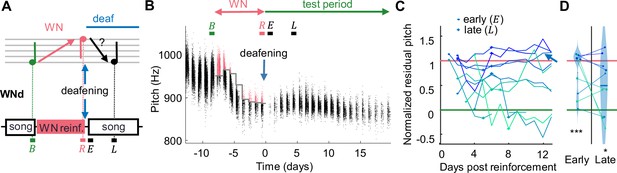

Recovery of pitch target is impaired after deafening.

(A) WNd birds were first pitch-reinforced using white noise (WN) and then deafened by bilateral cochlea removal. Analysis windows (letters) as in Figure 1. (B) Syllable pitches (dots, red = reinforced syllables) of example WNd bird that shifted pitch down by d' = -2.7 during WN reinforcement and subsequently did not recover baseline pitch during the test period. (C) WNd birds (N = 10) do not recover baseline pitch without auditory feedback (circles = early window after deafening events, cross = late). (D) Violin plots of same data restricted to early and late analysis windows, lines connect individual birds (***p<0.001, *p<0.05, two-tailed t-test of NRP = 0).

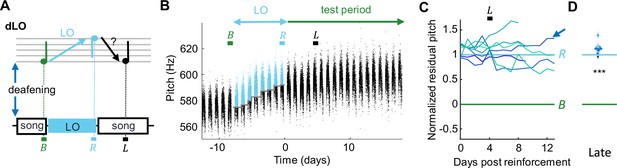

Deaf birds do not recover pitch target after light-induced mismatch.

(A) dLO birds were first deafened and then pitch-reinforced using a brief light-off (LO) stimulus. Analysis windows (letters) as in Figure 1. (B) Syllable pitches (dots, blue = LO-reinforced syllables) of example dLO bird that shifted pitch up by d' = 3.5 within a week, but showed no signs of pitch recovery during the test period. (C) dLO birds (N = 8) do not recover baseline pitch without auditory feedback. (D) Violin plots of same data restricted to the late analysis window (***p<0.001, two-tailed t-test of NRP = 0).

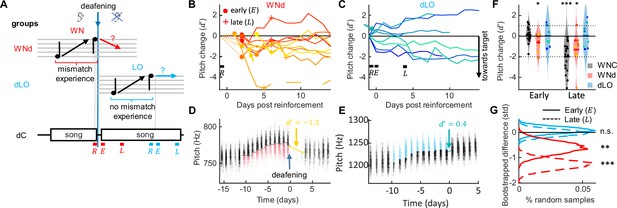

Target mismatch experience is necessary for revertive pitch changes.

(A) WNd birds heard a target mismatch during reinforcement whereas dLO birds did not. dC birds were not pitch reinforced, their analysis windows (letters as in Figure 1) matched those of manipulated birds in terms of time since deafening. (B, C) Pitch change between the last 2 hr of reinforcement () and the pitch of successive days aligned to the first 2 hr of song after withdrawal of reinforcement in std for WNd (red, B) and dLO (blue, C) birds. Early and late windows are marked with markers (dots, crosses) in (B) and letters (, ) in (C). Curves are plotted such that pitch changes toward the target are pointing down (see ‘Materials and methods’). Example birds shown in (D, E) are marked with arrows. (D, E) Syllable pitches (dots, red = WN reinforced, blue = LO-reinforced syllables) of example WNd (D) and dLO (E) bird. (F) WNd (red) perform both early and late pitch changes in the direction of the baseline target (by about one standard deviation, * p<0.05, ***p<0.001, one-tailed t-test, N=10 WNd birds and N = 8 dLO birds), similar to WNC (gray) and unlike dLO (blue) birds without mismatch experience. Dotted lines mark y-range displayed in (G) Bootstrapped pitch differences between reinforced WNd (red) and dLO (blue) and 10,000 times randomly matched dC birds, shown for early (solid line) and late (dashed line) analysis windows. The stars indicate the bootstrapped probability of a zero average pitch difference between reinforced and dC birds (n.s. not significant, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, N=10 WNd birds and N = 8 dLO birds).

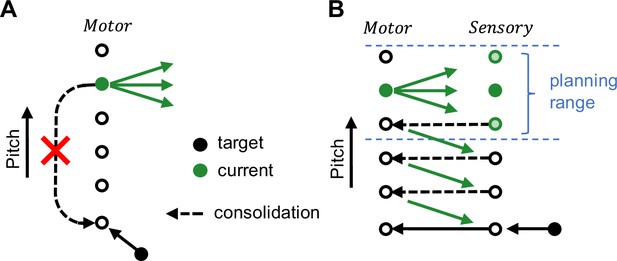

Schematic illustrating the goal-directed planning of vocal changes.

(A) Without practice, birds cannot recover a distant motor target (black filled circle) far away from the current motor output (green filled circle). (B) Without auditory experience, birds can make motor changes (green arrows) toward a target within a small range, we refer to this range as the (overt) planning range (blue). To recover a distant target (black filled circle) beyond the planning range, birds need auditory experience (green circles under Sensory), presumably to consolidate (dashed arrows) the overt motor changes.

Additional files

-

MDAR checklist

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/90445/elife-90445-mdarchecklist1-v2.docx

-

Supplementary file 1

Bootstrapped pitch differences between reinforced and deaf control birds.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/90445/elife-90445-supp1-v2.xlsx