Separating the control of moving and holding in human post-stroke arm paresis

Figures

Framework and experiment setup.

(A) A patient exhibiting a typical flexor posture at rest. Dashed arrows indicate elements of the posture: shoulder depression, arm adduction/internal rotation, elbow flexion. If one were to physically constrain the hand in a position away from the resting posture, the torques involved in each component of the abnormal resting posture translate to a force on the hand (sketched as a blue arrow); we thus designed an experiment to measure the resting force bias on the hand, as a marker of the overall postural abnormality. The goal was to compare resting postural force biases to active movement control in the same area (B). (C) Experiment setup. The participant holds the handle of the robotic arm; reach targets and cursor position are projected on a screen on top; for arm support, the participant’s arm is strapped on an armrest (c) connected to an air sled (a) which rests on the table. Air is provided through the tube labeled (b). (D) Top-down view of setup, illustrating the different hand positions where resting postural forces were measured in Experiment 1 (open circles). Also shown are the five target positions used in the reaching and holding task for Experiment 2 (filled red circles). The gray box indicates the workspace depicted in Figure 2. (E) Examples of measurements of resting force biases. Each panel shows the evolution of resting forces during the 5 s holding period for one participant (same participants as in Figure 2), taken at positions close to midline and distant from the body, under the same condition (paretic arm, arm support given). Solid lines indicate the force on the x-axis (positive values indicate forces towards the left), whereas dashed lines indicate the force on the y-axis (positive values indicate forces towards the body). The shaded area indicates the time window over which forces were averaged to estimate the resting bias, illustrating how resting biases were relatively stable by the 2 s mark. Note that the third panel includes one trial (blue) which was rejected following visual inspection as described in Materials and methods – Data Exclusion Criteria, due to instability in force production and movement during the hold period.

Examples of resting postural force biases.

Shown are three stroke patients and one healthy control. Arrows indicate magnitude and direction of abnormal resting postural forces as measured at the hand at each location. Isoclines and the corresponding color levels provide a visual representation of where these biases would tend to direct the hand (from red towards blue). These isoclines represent different levels of the (spatial) integral of the posture bias-field (with zero referring to the isocline passing through the center position). Postural bias force vectors cross these isoclines perpendicularly. Please see the shared analysis code at OSF for details on how this visual aid was constructed. The red dots are the reach targets, with the center location circled (used in Experiment 2). Note how abnormalities in the paretic side are considerably stronger when arm support is removed. FM-UE: Fugl-Meyer score for the Upper Extremity (0–66).

Average resting postural force biases.

(A) Average resting postural forces for the paretic (red) and non-paretic (cyan) arms of patients (n=16), as well as control participants (gray, n=9), illustrating how abnormal forces in the paretic arm are stronger in more distant targets and attenuated when arm support is provided (lighter shades). To average across left- and right-hemiparetic patients, left-arm forces were flipped left to right. (B) Corresponding average resting postural force magnitudes and resting postural force directions (0 indicating the 3 o’clock direction, with negative values indicating clockwise directions). Error bars indicate mean ± SEM (circular mean ± SEM in the case of movement directions).

Three aspects of active motor control that we tested in Experiment 2.

We separately examined the early part of the reaching movement (blue) and the late part, when the arm was coming to a stop (red). This was done by studying both unperturbed movements at different stages and movements that were perturbed with brief force pulses. In addition, we examined active holding control after the movement was over (black), using perturbations that tried to move the arm away from the held point. Shown is an example of trajectory and speed profiles from the reaching and coming-to-a-stop parts of a trial (left) and active holding against a perturbation after the trial was over (right).

Abnormal resting postural force biases do not interact with active reaching.

(A) Target array for Experiment 2 (movement task), illustrating the 5 start/end points of reaches and the 8 movement directions. (B) Example outwards trajectories (unperturbed trials) for a patient (cyan: non-paretic side; red: paretic side) and a healthy control (gray). (C) Subject-averaged reach performance based on either time (top) or path length to target (bottom) indicates impaired reaching control in patients’ paretic side. (D–F) Within-subject analysis of whether resting postural forces at movement start bias early movement towards their direction. (D) Sketch illustrating the concept behind this analysis. Assuming a movement from a start position subject to a strong rightwards resting bias (Fstart), will that translate to a corresponding rightwards movement bias which can be expressed as the early reach angle θstart,? (E) For each individual, we selected the target direction for which the counter-clockwise (CCW) component of Fstart was the strongest (red) vs. the target direction for which the clockwise (CW) component was the strongest (blue). The left panel shows this selection for an example participant: postural forces at start position were projected lateral to the movement direction, allowing us to select movement directions for which the lateral component was directed the strongest CCW or CW. The right panel shows the magnitude of these selected components across all patients. (F) Left: Corresponding movement trajectories (rotated so start position is at the bottom and end position at the top) for the directions selected for the same example participant. Right: Average initial angular deviations, θstart, across the selected directions for each participant. Note the lack of difference between the instances for which the CCW vs. the CW component of Fstart was the strongest, and thus no evidence that Fstart impinges upon the movement. (G–I) same as D-F but for endpoint resting postural forces, Fend and endpoint deviations, θend. Error bars indicate SEM. Data from n=16 stroke patients and n=9 healthy control participants. Comparisons in F and I indicate paired t-tests; NS=not significant.

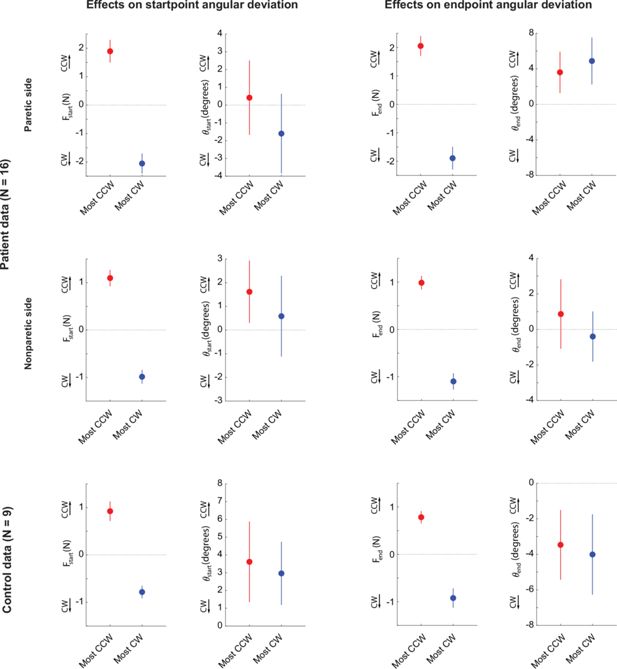

Relationships between active reaching and resting posture biases for the non-paretic side of patients and for controls.

(A) Reproduction of Figure 5E (right) and Figure 5F (right) for reference (data from the paretic side of stroke patients). Left: resting biases corresponding to the instances (target directions) where the component of the resting bias lateral to the target direction was the most CW (blue) vs. the most CCW-oriented (red). Right: corresponding initial angular deviations. (B) Same analyses for the non-paretic arm of stroke patients. (C) Same analyses for the control data.

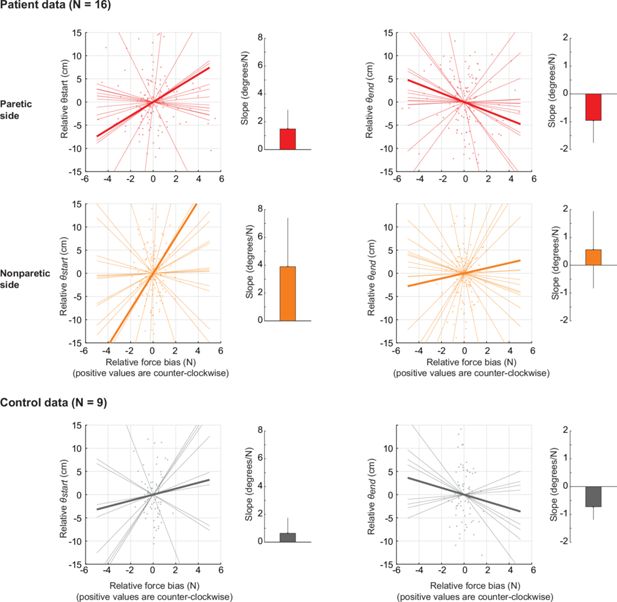

Estimating the sensitivity of active reaching to resting posture biases.

This analysis, in contrast to the main analysis in Figure 5E/F which only compares the instances where resting biases are the most CW/CCW related to movement direction, takes all possible instances and uses linear regression to estimate the sensitivity (slope) of initial and endpoint angular deviations to resting biases on the start and target positions, respectively. (A) Analysis for the patients’ paretic arm. Left: Shown is a scatter plot of the relative (i.e. mean-subtracted) initial angular deviation (θstart, y-axis) against the relative force bias lateral to movement (Fstart, x-axis). Each dot represents one movement direction for one participant. Both x- and y-axis data were mean-subtracted separately for each participant. The thin lines indicate linear fits for each participant; the thick line indicates the average of those fits. The bar graph to the right shows the average slope (sensitivity)± SEM. Positive slopes indicate that angular deviations follow the posture bias at start; there is no evidence of a positive slope as shown in the bar graph, in line with our main analysis in Figure 5F. Right: same but for endpoint angular deviations (θend) against resting biases at the target (Fend). (B) and (C) Same as in (A) but for the non-paretic arm of patients and for healthy controls, respectively.

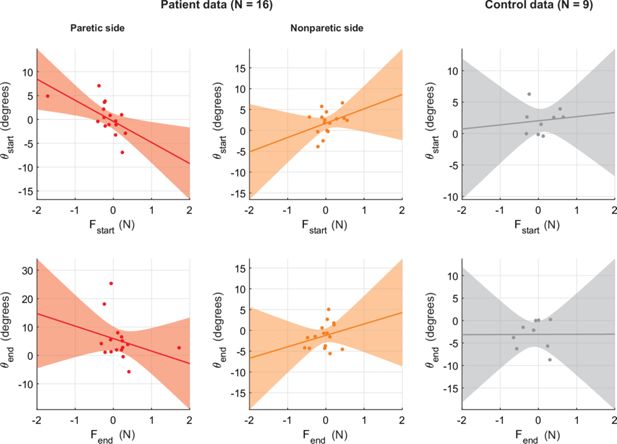

Across-individual correlations between resting bias and movement kinematics.

(A) Scatter plot of average θstart the average component of Fstart lateral to target direction. Positive numbers indicate counter-clockwise θstart and Fstart. Solid line indicates linear fit; shading illustrates the associated 95% confidence interval. Plots indicate a lack of positive relationship. While this is in line with the main analysis, these across-individual relationships can only provide limited evidence since they may average out opposing contributions of resting biases. This is why our main analysis focuses on within-individual differences across different movement directions. (B, C) Same as (A) but for the non-paretic side of patients (B) and for healthy controls (C). (D–F) Same as (A–C) but for approach angle close to the endpoint, θend.

Repetition of the analysis in Figure 5E/F (top) and 5 H/I (bottom) but with resting biases calculated without trial rejection, showing similar results (lack of relationship between θstart and θend with Fstart and Fend, respectively).

Responses to pulse perturbations during movement are not affected by resting postural force biases.

(A) Examples of perturbed (red: perturbed with CCW pulse; blue: perturbed with CW pulse) and unperturbed (gray) outward trajectories - same individuals as in Figure 3B. (B) Lateral velocity (positive: CCW to movement) before and after pulse onset, and corresponding responses from controls (gray), illustrating how patients, in response to the pulse, take longer time to settle and tend to experience larger lateral deviations compared to controls. (C) Summary performance measures for patients and controls, indicating impaired performance with the paretic side: settling time (left) and maximum lateral deviation on pulse direction (right). (D) Within-individual analysis: here, for each individual, we selected the movements for which the starting-position resting postural force would be either the strongest CCW or CW (left); we then examined the corresponding settling time (middle) and maximum lateral deviations (right). We find no effects of the most CCW vs. most CW resting postural forces in either case: there is no evidence for either reduced settling time or increased maximum lateral deviation for instances where pulse and resting bias are most opposing (open circles) compared to the instances where pulse and resting bias are most aligned (filled circles). Error bars indicate SEM; data from n=16 stroke patients and n=9 healthy control participants.

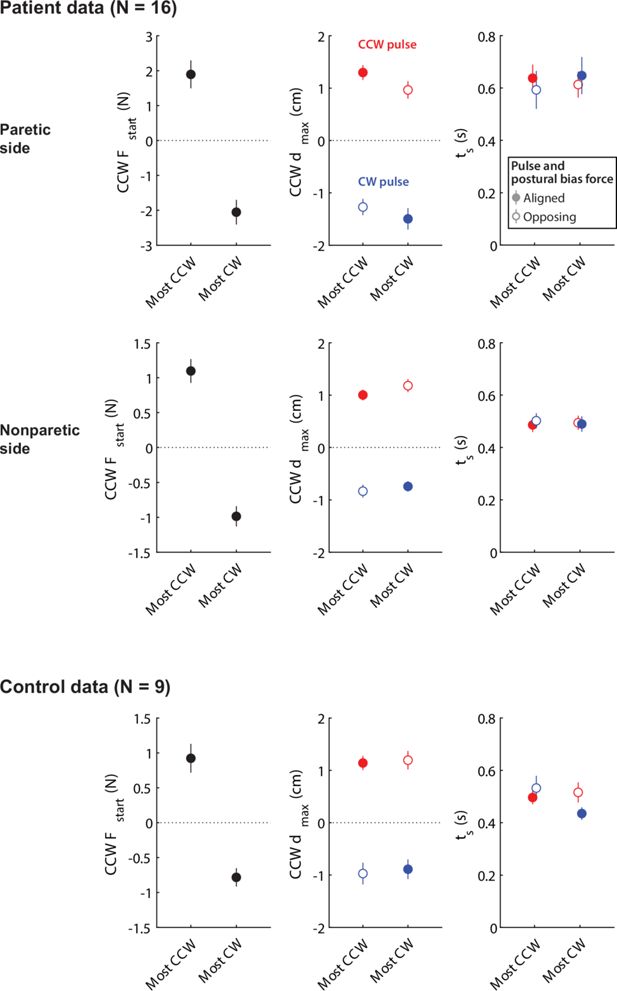

Relationships between responses to pulse perturbations and resting posture biases for the non-paretic side of patients and for controls.

Top row: Reproduction of Figure 6D for reference (data from the paretic side of stroke patients). Middle row: Same analyses for the non-paretic arm of stroke patients. Bottom row: Same analyses for the control data. Note, in all cases, the lack of difference between the instances where postural biases were the most aligned vs. the most opposed to the pulse.

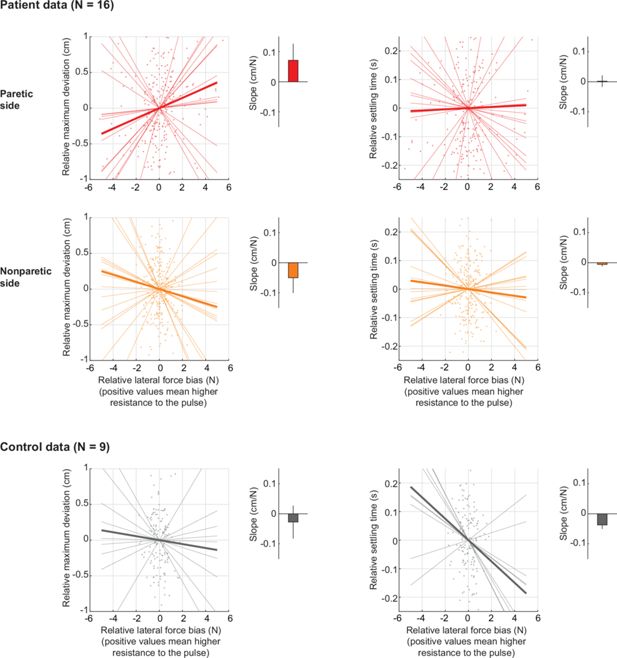

Estimating the sensitivity of movement perturbation responses to resting posture biases.

This analysis, in contrast to the main analysis in Figure 6D which only compares the instances where resting biases are the most aligned vs. the most opposed to the pulse perturbations, takes all possible instances and uses linear regression to estimate the sensitivity (slope) of maximum deviation to resting biases. (Top row) Analysis for the patients’ paretic arm. Left: Shown is a scatter plot of the relative (i.e. mean-subtracted) maximum deviation (y-axis) against the relative force bias in the perturbation direction (x-axis), with positive values indicating increased resistance to the pulse. Each dot indicates one movement direction/pulse sign combination for one participant. Both x- and y-axis data were mean-subtracted separately for each participant and pulse type. The thin lines indicate linear fits for each participant; the thick line indicates the average of those fits. The bar graph shows the average slope (sensitivity)± SEM. Negative slopes indicate interaction with responses to perturbations during active movement. There is no evidence of a negative slope as shown in the bar graph, in line with our main analysis in Figure 6D. Right: Same as left, but for the relative settling time. (Middle row) and (Bottom row) Same as in (A) but for the non-paretic arm of patients and for healthy controls, respectively.

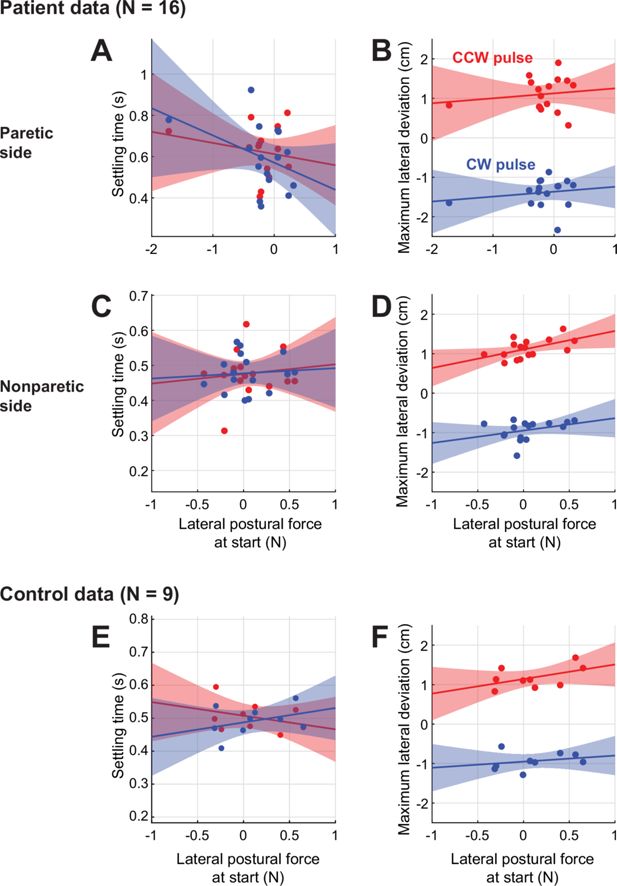

Across-individual correlations between resting bias and movement perturbation responses.

(A) Across-patient comparison between settling time and lateral postural bias forces on movement start. Paretic data shown. Red: CCW pulse; Blue: CW pulse. (B) Same as (A), but for (signed) maximum lateral deviation for the two pulse types. (C,D) Same as (A,B) but for nonparetic data. (E,F) Same as (A,B) but for control data.

Repetition of the analysis in Figure 6D but with resting biases calculated without trial rejection, showing similar results (lack of effect of resting biases upon the response to the force pulse).

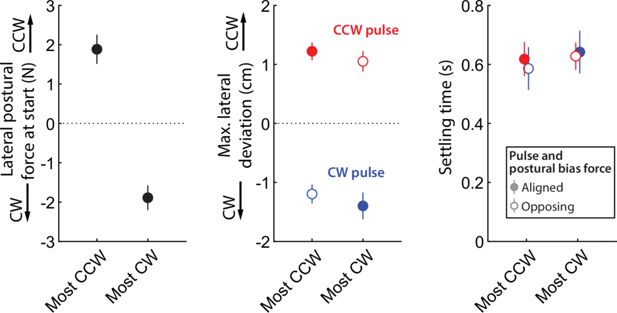

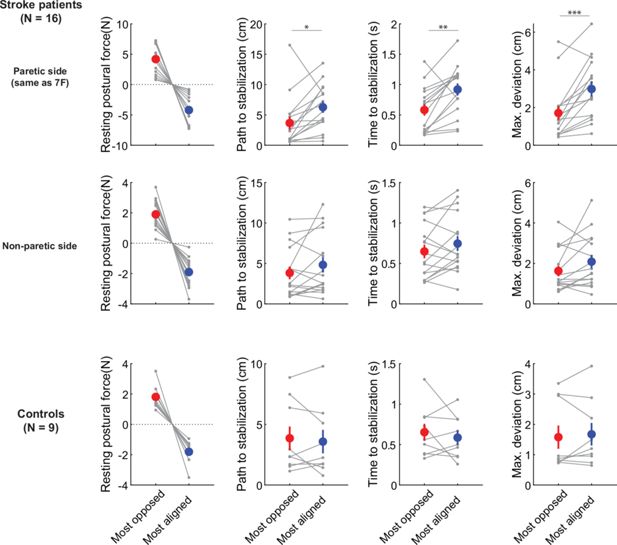

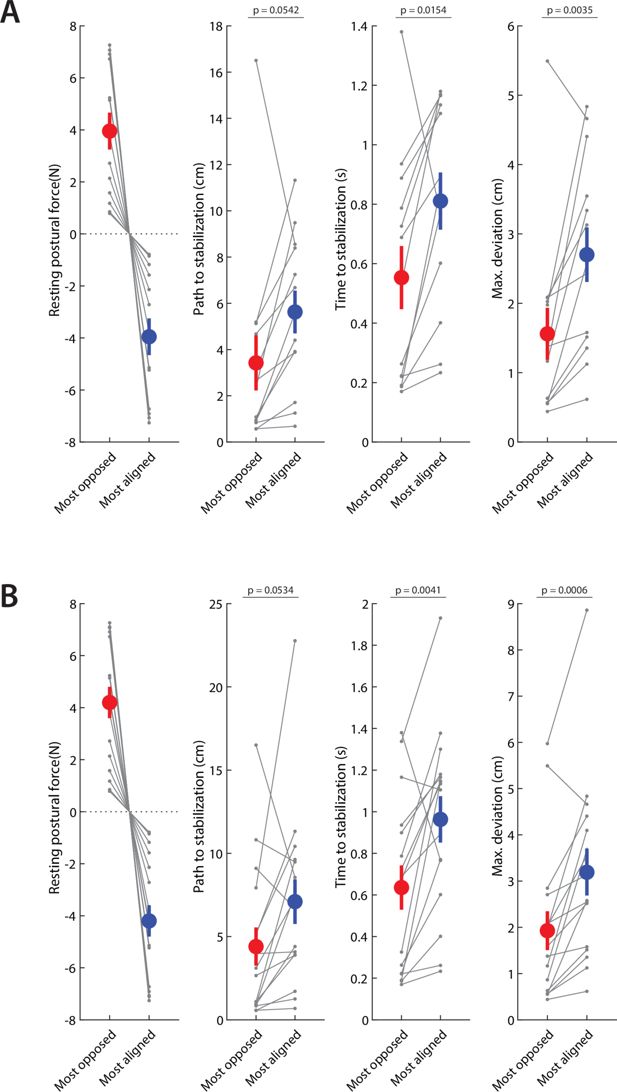

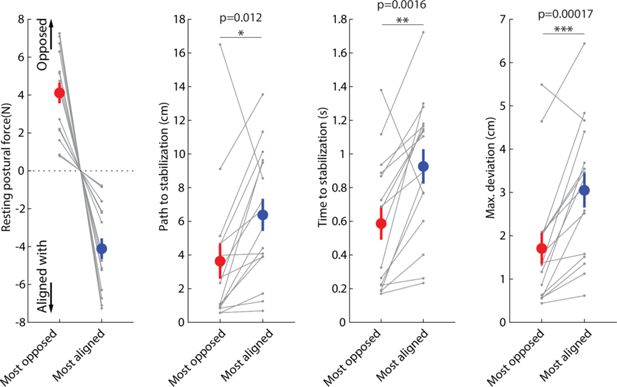

Responses to release perturbations during holding and their relationship to resting postural forces.

(A) Time course of the perturbation. (B) Example responses (all for the same position in the workspace) from two patients (top row) and two controls (bottom row). (C) Corresponding imposed force directions, the abrupt removal of which perturbs the movement in the opposite direction (compare with B). (D) Examples of speed profiles after the sudden release of the imposed hand force, averaged for all trials at the same position for each participant. A dashed line indicates the 2 cm/s threshold used to assess time to stabilize. Left; example patient (paretic side); Right; example control. Colors correspond to different directions of the imposed hand force. (E) Summary of performance metrics after the perturbation for the paretic and non-paretic side of patients (n=16) and healthy controls (n=9). (F) Within-subject analysis of the relationship between resting postural forces in the direction of the perturbation vs. performance against the perturbation. For each individual, we selected the two position/perturbation direction combinations for which resting postural forces were either the most opposed (red) to the perturbation or the most aligned (blue) with it. From left to right: forces in selected position/perturbation direction combinations; corresponding path traveled to stabilization; corresponding time to stabilization; corresponding maximum deviation. Note how the most-opposed resting bias for each patient is equal and opposite to their most-aligned resting bias. This is because the same resting bias, when projected along the direction of two oppositely directed perturbations (illustrated in C), would oppose one with the same magnitude it would align with the other. This analysis suggests that resisting postural perturbations and restoring hand position after the perturbation was indeed easier when resting postural forces opposed, rather than were aligned with, the perturbation. Gray dots indicate individual data; colored dots and error bars indicate mean ± SEM. Comparisons indicate paired t-tests; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

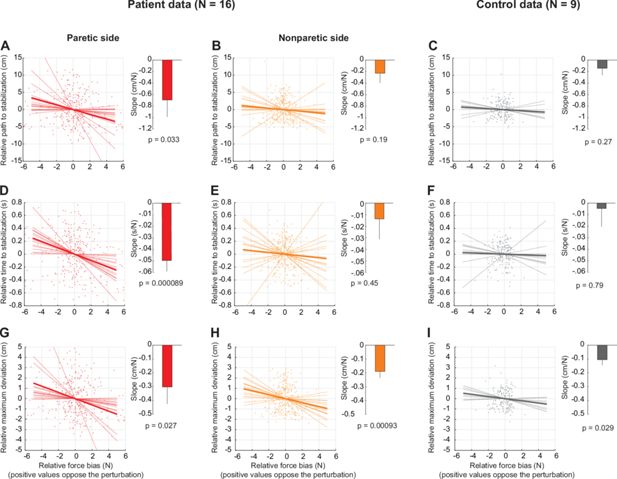

Relationships between responses to static release perturbations and resting posture biases for the non-paretic side of patients and for controls.

Top row: Reproduction of Figure 7F for reference (data from the paretic side of stroke patients). Middle row: Same analyses for the non-paretic arm of stroke patients. Note that, while the magnitude of the corresponding resting biases is lower compared to the paretic arm, the outcome variables (path to stabilization, time to stabilization, and maximum deviation) are nominally (but not significantly) lower in the case where resting biases are most opposed to the perturbation. Bottom row: Same analyses for the control data.

Estimating the sensitivity of active holding control to resting posture biases.

This analysis, in contrast to the main analysis in Figure 7F which only compares the instances where resting biases are the most aligned vs. the most opposed to the static release perturbation, takes all possible instances and uses linear regression to estimate the sensitivity (slope) of the outcome variables to resting biases. (A) Analysis for the patients’ paretic arm. Shown is a scatter plot of the relative (i.e. mean-subtracted) path to stabilization (y-axis) against the relative force bias in the perturbation direction (x-axis). Both x- and y-axis data were mean-subtracted separately for each participant. The thin lines indicate linear fits for each participant; the thick line indicates the average of those fits. The bar graph to the right shows the average slope (sensitivity)± SEM, which was, in this case, significantly negative in line with an effect of resting bias on patients’ performance against the holding perturbation. (B) and (C) Same as in (A) but for the non-paretic arm of patients and for healthy controls, respectively. (D–F) Same as A-C but for relative time to stabilization. (G–I) Same as A-C but for relative maximum deviation. Note how all three metrics demonstrate that patients are more able to resist and recover from the static release perturbation when resting biases are directed against the perturbation (A,D,G). In turn, this supports the evidence shown in Figure 7F that resting biases interact with active holding control.

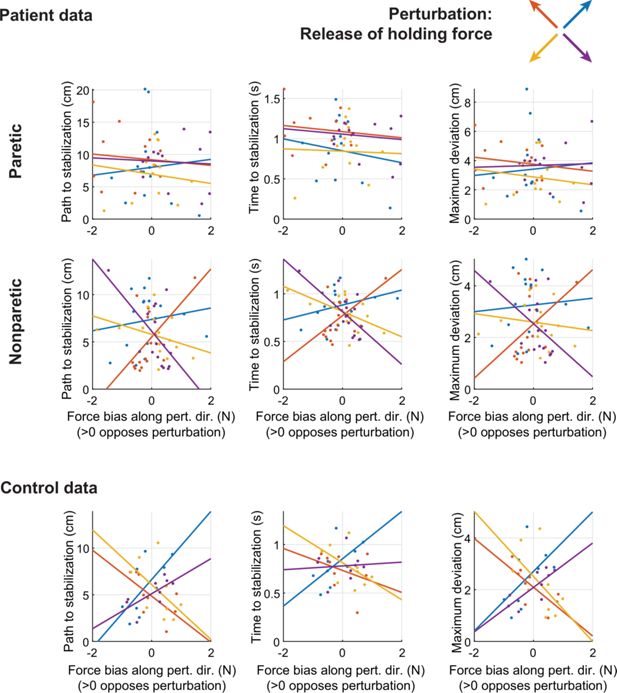

Across-patient comparisons between average postural biases (projected along the direction of the release perturbation) and different metrics of performance against the release perturbation: path to stabilization (left column); time to stabilization (middle column); and maximum deviation (right column).

Different colors indicate data related to the four different release perturbation directions. Lines indicate linear fits. Positive values in the x-axis indicate biases that would oppose the perturbation. Note the limitations of these inter-individual analyses (which also hold for Figure 5—figure supplement 3, Figure 6—figure supplement 3): First, averaging these effects for each individual would average out opposing contributions of resting biases; here, because the perturbations come in exactly opposing pairs, this would average to zero, which is why we show these relationships for each perturbation separately instead (which may result in higher measurement noise). Second, the power of correlation analyses may be diluted by inter-individual differences in other factors, such as overall stiffness. Focusing on within-individual differences addresses both these issues.

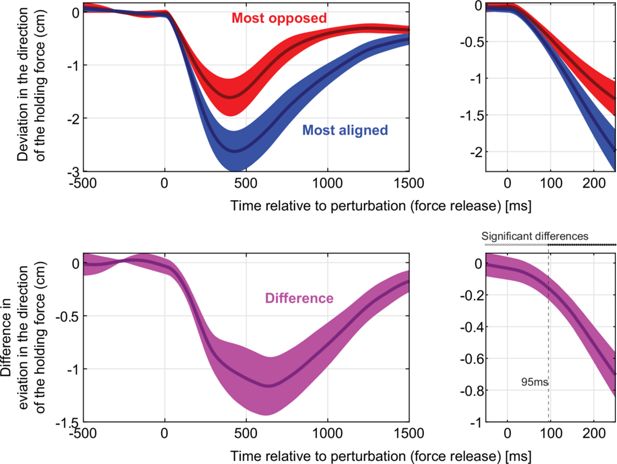

Time course of responses to the static release perturbation.

Top: deviation in the direction of the holding force for the cases where the resting bias was the most aligned (blue) vs. the most opposed (right) to the perturbation. The right panel zooms in the first 250ms following the release. Bottom: difference between the most-opposed vs. most-aligned data shown on top. On the right panel, statistically significant differences emerge 95ms after the release.

Repeating the analyses in Figure 7F to ensure no systematic effects of missing data.

In some holding perturbation trials, patients took a long time to reach the stabilization criterion described in the previous section; mistakenly, our setup limited its recording time to only the first 2 s after force release. The exact time to stabilization thus could not be measured for these particular trials, so they had to be excluded from analysis. Although only 13.2 ± 3.3% (mean ± SEM) of paretic stabilization trials were thus excluded in the patient population (1.4 ± 0.4% in their non-paretic side, 0.4 ± 0.4% [two trials] in controls), there were three patients for whom excluded trials were 25% or more of all paretic trials. To ensure there are no systematic effects of this issue, we repeated the analysis of Figure 7F (a) by excluding these three patients altogether (shown in A) or (b) by assigning a value of 2.0 s to the affected trials. In both cases, we found results similar to our main analysis (shown in B). Both analyses yielded results similar to our main analysis.

Repetition of the analysis in Figure 7F but with resting biases calculated without trial rejection, showing similar results (performance against the static release perturbation is better when the resting biases are directed against the perturbation, and worse when the resting biases are aligned with the perturbation, showing interaction between resting biases and active holding control).

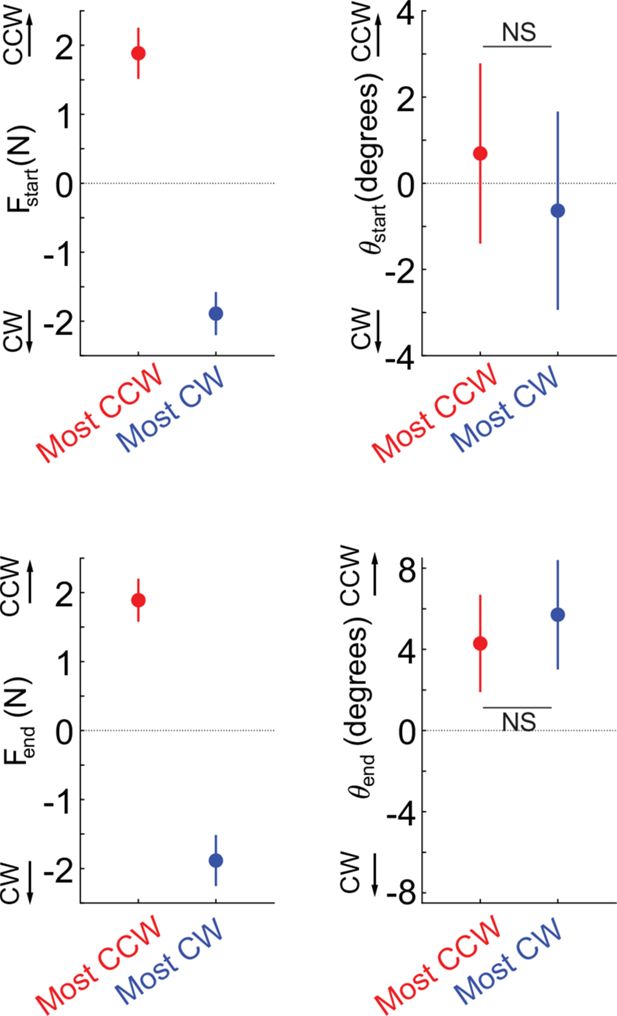

Direct comparison of the effects of resting force biases on holding perturbations vs. pulse perturbations.

Response Asymmetry Indices (RAIs) are shown for holding (red) vs. moving/pulse (blue) perturbations. Positive values indicate a response asymmetry in line with an effect of resting force biases. Individual data (n=16 patients) are shown in black dots. Error bars indicate SEM. Comparisons indicate paired t-tests.

Relationship between resting force biases and abnormal synergies.

Across-patient (n=16) relationships of FM-UE (/66, higher scores indicating lower impairment) and resting postural force magnitudes, for distant (green) and near (blue) target positions, with (left) and without support (right). Note the strong effects of arm support, proximity, and FM-UE. Lines indicate linear fits; shading indicates 95% confidence interval for each fit.

Tables

Patient characteristics.

FM-UE: Fugl-Meyer Assessment for the Upper Extremity; ARAT: Action Research Arm Test.

| ID | Age (5 years range) | Sex | Time since stroke | Handed-ness | Paretic arm | FM-UE (/66) | ARAT (/57) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S001 | 76–80 | M | 2 years | Right | Left | 57.5 | 57 |

| S002 | 51–55 | M | 6 years | Right | Left | 40 | 47.5 |

| S003 | 66–70 | F | 7 years | Right | Right | 34.5 | 19 |

| S004 | 26–30 | F | 5 years | Right | Left | 55.5 | 43.5 |

| S005 | 76–80 | M | 13 months | Right | Right | 43.5 | 34 |

| S007 | 51–55 | F | 2 months | Left | Right | 63 | 57 |

| S008 | 51–55 | F | 14 months | Right | Left | 41 | 25 |

| S009 | 56–60 | F | 5 years | Right | Left | 22 | 3 |

| S010 | 66–70 | M | 5 years | Right | Left | 20 | 12 |

| S011 | 41–45 | F | 20 months | Right | Right | 64 | 57 |

| S012 | 46–50 | M | 6 years | Right | Left | 18.5 | 6.5 |

| S013 | 66–70 | M | 9 years | Right | Left | 14 | 8 |

| S014 | 41–45 | F | 16 months | Right | Left | 40 | 39.5 |

| S015 | 61–65 | F | 10 years | Right | Left | 22 | 4.5 |

| S016 | 36–40 | F | 21 months | Amb. | Right | 62.5 | 57 |

| S017 | 46–50 | M | 3 months | Right | Left | 15 | 3 |

Summary of patient and control characteristics.

FM-UE: Fugl-Meyer Assessment for the Upper Extremity (/66); ARAT: Action Research Arm Test (/57). MoCA: Montreal Cognitive Assessment (/30). Here, ± indicates standard deviation.

| Stroke patients | Controls | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 16 | 9 |

| Age | 58.5±17.8 | 62.6±15.2 |

| Gender | 7 M/9 F | 3 M/6 F |

| Paretic side | 11 L/5 R | n/a |

| FM-UE | 38.3±18.2 | 66.0±0.0 |

| ARAT | 29.6±21.8 | 57.0±0.0 |

| MoCA | 24.9±3.1 | 28.1±1.6 |

| Time since stroke | [2 months,10 years] | n/a |