Plasticity of the proteasome-targeting signal Fat10 enhances substrate degradation

Figures

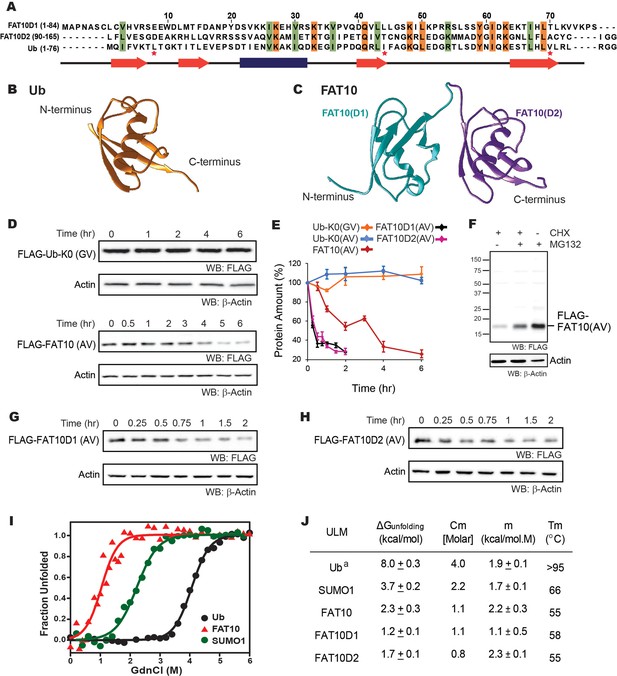

The in-cellulo and in-vitro stability of Fat10 and its domains were compared against ubiquitin.

(A) Structure-based sequence alignment of Fat10D1 (PDB: 6gf1), Fat10D2 (PDB: 6gf2), and ubiquitin (PDB: 1ubq). Conserved hydrophobic and identical residues in Fat10D1, Fat10D2, and ubiquitin are highlighted in light green and orange colors. The L8-I44-V70 residues that create a ‘hot spot’ of interactions in ubiquitin are marked with a red asterisk. (B) Structure of ubiquitin (1UBQ; orange) and (C) Homology model structure of full-length Fat10 where Fat10D1 is colored cyan, and Fat10D2 is colored purple. (D) FLAG-UbK0(GV) and FLAG-Fat10(AV) protein levels are plotted against time. The C-terminal GG residues are substituted with GV or AV to prevent conjugation to the cellular substrates. HEK293T cells were transfected with either FLAG-Ub or FLAG-Fat10, treated with Cycloheximide, and lysed at different time points. The lysates were separated on SDS PAGE gels and blotted with anti-FLAG antibodies. (E) Quantified protein levels of FLAG-UbK0(GV) (n=3), FLAG-UbK0(AV) (n=2), and FLAG-Fat10(AV) (n=3) are plotted against time after normalizing with β-Actin. (F) HEK293T cells were transfected with Fat10, treated with/without Cycloheximide, and proteasomal inhibitor MG132. The lysates were separated on SDS PAGE gels and blotted with anti-FLAG antibodies. (G) Similar to (D), showing degradation of FLAG-Fat10D1(AV) and (H) FLAG-Fat10D2(AV) after cycloheximide treatment. Quantified protein levels (n=3) of FLAG-Fat10D1(AV) and FLAG-Fat10D2(AV) are plotted in (E). (I) GdnCl melt curves of Fat10, Ub, and SUMO1. Normalized mean ellipticity shift is plotted against GdnCl concentration. (J) A table with the stability parameters of Ub, SUMO1, Fat10, and Fat10 domains is provided. (a: Reference Wintrode et al., 1994).

-

Figure 1—source data 1

Original file for the Western blot analysis in Figure 1D–H (anti-FLAG, anti-actin).

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/91122/elife-91122-fig1-data1-v2.zip

Comparison of Fat10 with other ULMs.

(A) List of Ubiquitin-Like Modifiers (ULMs) with their Uniprot and PDB is used in making the phylogenetic tree. (B) The structure of Fat10D1 (6GF1) (Blue) and Fat10D2 (6GF2) (purple) is superimposed onto the structure of ubiquitin (1UBQ) (orange). (C) Table represents RMSD (Å) between different ULM pairs used to make phylogenetic trees. (D) Phylogenetic tree of 11 ULM based on their RMSD across the available structure in PDB. (E) HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-UbK0(AV) and treated with cycloheximide and for 6 hr. The lysates were separated on SDS page gels and blotted with anti-FLAG antibodies. (F) HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-Fat10D1(AV) and treated with/without cycloheximide and proteasomal inhibitor MG132 for 6 hr. The lysates were separated on SDS page gels and blotted with anti-FLAG antibodies. (G) The cells were transfected with FLAG-Fat10D2(AV), then treated and probed as in (D).

-

Figure 1—figure supplement 1—source data 1

Original file for the western blot analysis in Figure 1—figure supplement 1F and G (anti-FLAG).

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/91122/elife-91122-fig1-figsupp1-data1-v2.zip

-

Figure 1—figure supplement 1—source data 2

Original file for the western blot analysis in Figure 1—figure supplement 1E (anti-FLAG, anti-actin).

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/91122/elife-91122-fig1-figsupp1-data2-v2.zip

Characterizing purified Fat10.

(A) Far-UV CD spectra and (B) 15 N-1H HSQC spectra of purified Fat10. (C) The thermal melt curve of Fat10 and SUMO1, where the change in ellipticity is normalized and plotted against temperature.

Characterizing individual D1 and D2 domains of Fat10.

(A) Far-UV CD spectra of purified Fat10D1 (Blue) and Fat10D2 (Purple). (B) 2D 15 N-1H HSQC spectra with peak assignment of Fat10D1and (C) Fat10D2. (D) The GdnCl melt curves of Fat10D1 and Fat10D2. The thermal melt curve of (D) Fat10D1 and (E) Fat10D2, where the change in ellipticity is normalized and plotted against temperature.

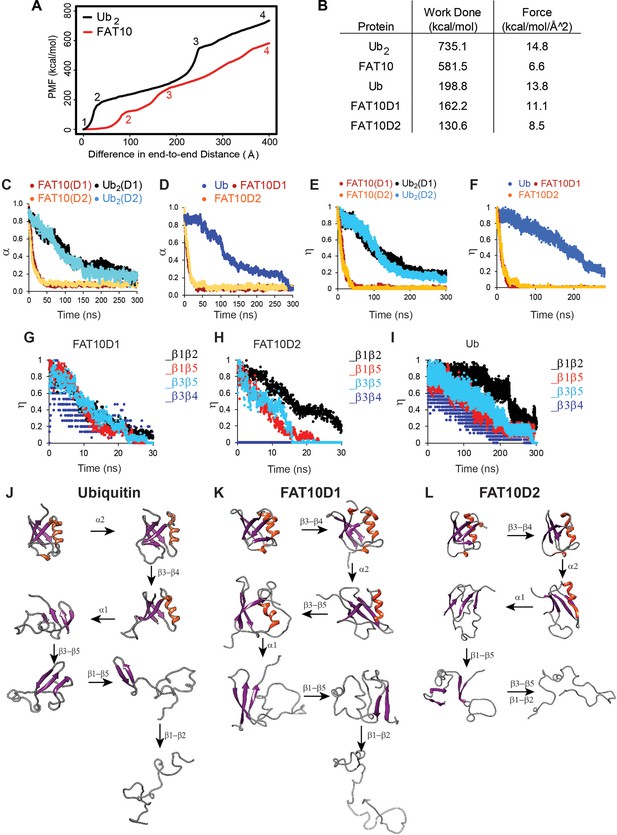

Unfolding studies of Fat10, di-ubiquitin (Ub2), Ub, and individual domains D1/D2 in Fat10 by MD simulations.

(A) ASMD of Ub2 and Fat10. The potential Mean Force (PMF) is plotted against the normalized end-to-end distance. Each unfolding event is marked by a number, whose corresponding conformation is given in Figure 2—figure supplement 1. (B) The work done to unfold the proteins by ASMD is provided. (C) Simulations of Fat10, di-ubiquitin (Ub2), Ub, and individual domains D1/D2 in Fat10 were performed at 450 K. The fraction of native contacts is defined as (α) and plotted against time. Fat10(D1) and Fat10(D2) are the D1 and D2 domains in Fat10. Ub2(D1) and Ub2(D2) are the two Ub domains in diubiquitin. The data is averaged over ten replicas. (D) is the same as (C) measured for individual domains Fat10D1, Fat10D2, and Ub. (E) The fraction of native beta-sheet backbone hydrogen bonds is defined as (η) and plotted for Fat10 and Ub2 against time. (F) is the same as (E) measured for individual domains Fat10D1, Fat10D2, and Ub. η is plotted for β1 to β5 of (G) Fat10D1, (H) Fat10D2, and (I) ubiquitin. The intermediate structures of the unfolding pathway in (J) Ub, (K) Fat10D1, and (L) Fat10D2 are shown, which were inferred from the fraction of backbone hbonds from ten replicas in the MD simulations.

Studying the mechanical unfolding of Fat10 and ubiquitin by steered MD.

The intermediates were observed during the adaptive steered molecular dynamics of (A) diubiquitin and (B) Fat10. (C) Adaptive Steered MD of Ub, Fat10D1, and Fat10D2. The potential Mean Force (PMF) is plotted against the normalized end-to-end distance. The pulling velocity is 1 Å/ns. Each unfolding event is marked by a number whose corresponding conformation is given in (D) Fat10D1, (E) Fat10D2, and (F) monoubiquitin.

Mechanical unfolding of Fat10 and di-ubiquitin by MD simulations is shown here.

The top panel is Fat10, and the bottom panel is di-ubiquitin. The PMF values of the two molecules are provided in between.

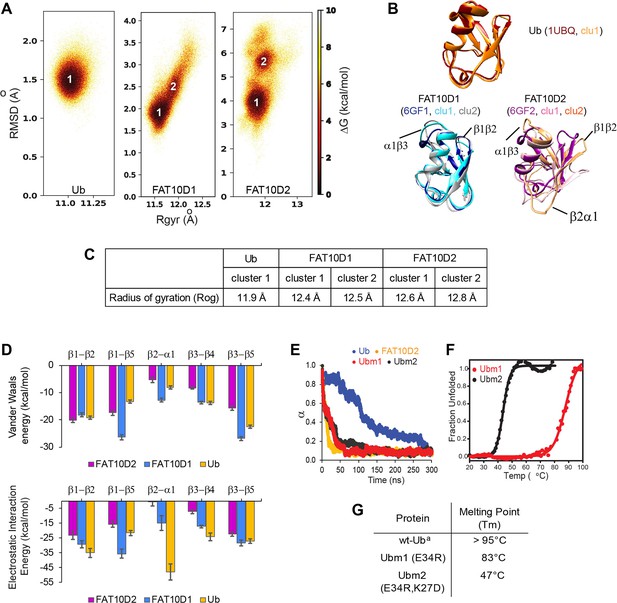

A comparison of Ub and Fat10 energetics was investigated by all-atom MD simulations.

(A) The free energy landscape of Fat10 domains and ubiquitin are plotted as a function of RMSD and radius of gyration (Rgyr) obtained from simulations across three replicas (3x2.5 μs) performed at 300 K. The minima from each cluster are numbered. (B) The corresponding conformation of each cluster in (A) is shown. The structures of the proteins, denoted by their pdb IDs, are provided for comparison. (C) The radius of gyration of the entire protein (Rog) for the minimas in Ub, Fat10D1, and Fat10D2 are provided. The Rgyr values do not account for long loops in the protein, while the Rog values include the complete protein. (D) The mean Van der Waals energy of interactions and electrostatic energy of interactions between different pairs of secondary structures obtained from simulations is plotted for Fat10 domains and ubiquitin. The error bars denote the standard deviation. One-way annova was performed (B1-B2; P = 0.0892; P>0.05, B1-B5; P = 0.0060; P<0.05, B2-A1; P = 0.0019; P<0.05, B3-B4; P = 0.0028; P<0.05, B3-B5; P = 0.1196 ; P>0.05) (E) The fraction of native contacts in Ubm1, Ubm2, Ub, and Fat10 domain against time at 450 K MD simulations. (F) The thermal melt curve of Ubm1 and Ubm2, where the change in ellipticity is normalized and plotted against temperature. (G) The melting point of ubiquitin mutants. (a: Reference Wintrode et al., 1994).

Effect of salt bridge substitutions on ubiquitin structure.

(A) The Cα root mean square fluctuations (RMSF) are plotted against residue numbers for the isolated domains Fat10D1, Fat10D2, and ubiquitin in the 300 K simulations. (B) The β2−α1 electrostatic interactions are mapped on Ub, Fat10D1, and Fat10D2 structures. The β2 and α1 are colored blue. The hydrogen bonds and salt bridges are shown as black lines. A Lys11-Glu34 salt bridge and two hydrogen bonds (Lys33-Thr14 and Lys29-Glue16) are observed in ubiquitin but absent in Fat10D1 and Fat10D2. (C) A K27-D52 salt bridge is observed in ubiquitin between the α1 helix and the α2−β4 loop. A black line shows the salt bridge. In Fat10D1, K34 is present in α1 at the position analogous to K27. However, a proline residue P59 is present at a similar position to D52 in Ub. Consequently, the salt bridge is absent in Fat10D1. In the Fat10D2 structure, the D140 sidechain is facing away from the K116; hence, the salt bridge has not formed. (D) The free energy landscapes of Ubm1 (E34K-Ub) and Ubm2 (E34K, K27D-Ub) are plotted as a function of RMSD and radius of gyration (Rgyr) obtained from simulations across three replicas (3x2.5 μs) performed at 300 K. The minima from each cluster are numbered. (E) Distributions of different conformations sampled were analysed by PCA analysis and the variation observed is mapped onto the structure of Ub. PC1 values scale the thickness of the ribbon and color (red). (F) and (G) are plotted similar to (E), but for the ubiquitin mutants Ubm1 and Ubm2, respectively. The black arrows indicate a gain in motions (fluctuations) for wild-type Ub. The blue open circles indicate the site of substitution.

Effect of salt bridge introduction on FAT10D1 structure.

A) The free energy landscape of Fat10D1m (D18K, T41E, P59D) is plotted as a function of RMSD and radius of gyration (Rgyr) obtained from simulations across three replicas (3x2.5 μs) performed at 300 K. (B) The Cα RMSF values are plotted for Fat10D1 and Fat10D1m. (C) The variation observed by PCA analysis is mapped onto the structure of Fat10D1. The thickness of the ribbon and color (red) is scaled by PC1 values. (D) Similarly plotted for Fat10D1m. The arrows indicate loss in dynamics (fluctuations) with respect to the wild-type protein. The blue open circles indicate the site of substitution.

The thermal unfolding of Fat10 domains and ubiquitin is shown here.

Fat10D1 is on the left and colored blue. Fat10D2 is colored purple and displayed in the middle. Ubiquitin is shown at the right and colored orange. The duration of simulations is shown at the bottom right. The kinetics of unfolding Fat10 domains are significantly faster than Ub.

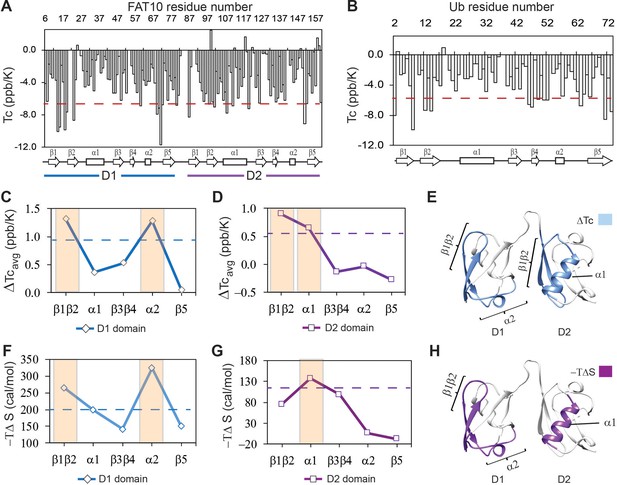

The local hbond stability and conformational entropy in Fat10 were measured by NMR spectroscopy.

Temperature coefficients (Tc) are plotted for Fat10 and ubiquitin in (A) and (B), respectively. The horizontal red line is (mean – S.D.), where the mean value is negative. High negative Tc values suggest weaker hbonds and disorder propensity. (C) The difference in average temperature coefficients (ΔTcavg) between the N-terminal Fat10 domain (D1) and ubiquitin, where ΔTcavg = Tc(Ub)avg - Tc(D1)avg. The blue dashed line is mean + error. (D) The difference in averaged temperature coefficients (ΔTcavg) between the C-terminal domain and Ub, where ΔTcavg = Tc(Ub)avg - Tc(D2)avg. The purple dashed line is the mean + error. Higher ΔTcavg values suggest weaker hbonds and destabilization in these Fat10 regions than ubiquitin. (E) The segments with high ΔTcavg values are colored light blue on the Fat10 structure. (F) The difference in conformational entropy -TΔSconf, where ΔSconf = SconfUb – SconfD1, was averaged for the various segments and plotted. The entropy values were calculated from the order parameters measured in Figure 4—figure supplement 2. The broken line denotes (mean + error). (G) Same as (F) except conformational entropy is calculated for the C-terminal Fat10 domain, such that ΔSconf = SconfUb – SconfD2. (H) The segments with -TΔS more than (mean + SD) are colored purple on Fat10 domains. Higher values of -TΔS suggest increased conformational flexibility in these Fat10 regions compared to ubiquitin.

The temperature dependence of amide chemical shifts.

(A) The Residual Sum Square (RSS) for each residue of Fat10 and (B) ubiquitin were calculated and plotted. (C) The averaged Tc of Fat10 and ubiquitin over various protein segments. Fat10(D1) and Fat10(D2) are two domains in Fat10. The ubiquitin segments are defined as β1β2: 2–22; α1: 23–34; β3β4: 35–50; α2: 51–63, and β5: 64–74. For the D1 domain in full-length Fat10, Fat10(D1), b1b2: 8–28, a2: 29–42, b3b4: 43–56, a2: 57–72 and b5: 73–85. For the D2-domain in full-length Fat10, Fat10(D2), β1β2: 85–110, α2: 111–121, β3β4: 122–143, α2: 144–153 and β5: 154–160. (D) and (E) are the Tc values of isolated Fat10 domains. The broken red lines denote Mean + SD. (F) and (G) errors for Tc calculation for the isolated Fat10 domains. (H) The averaged Tc of Fat10 domains and ubiquitin over various protein segments. Ub values are replotted here for comparison. (I) The difference in averaged temperature coefficients (ΔTcavg) between the isolated N-terminal domain and Ub, where ΔTcavg = Tc(Ub)avg - Tc(Fat10D1)avg. The blue line is mean +error. (D) The difference in averaged temperature coefficients (ΔTcavg) between the isolated C-terminal domain and Ub, where ΔTcavg = Tc(Ub)avg - Tc(Fat10D2)avg. The purple line is the mean + error.

Measurement of backbone dynamics in Ub and Fat10.

(A) The measured values of longitudinal relaxation rates (R1), transverse relaxation rates (R2), Nuclear Overhauser Enhancement (hetNOE), and order parameter (S2) are plotted for Ub. The ubiquitin secondary structure elements are provided on the top panel. (B) The measured R1, R2, hetNOE, and S2 values are plotted for the Fat10. The Fat10 secondary structure elements are provided on the top panel. The measured values are collected at the field of 800 MHz.

Stability comparison of Ub and Fat10 conjugated substrates in cellular conditions.

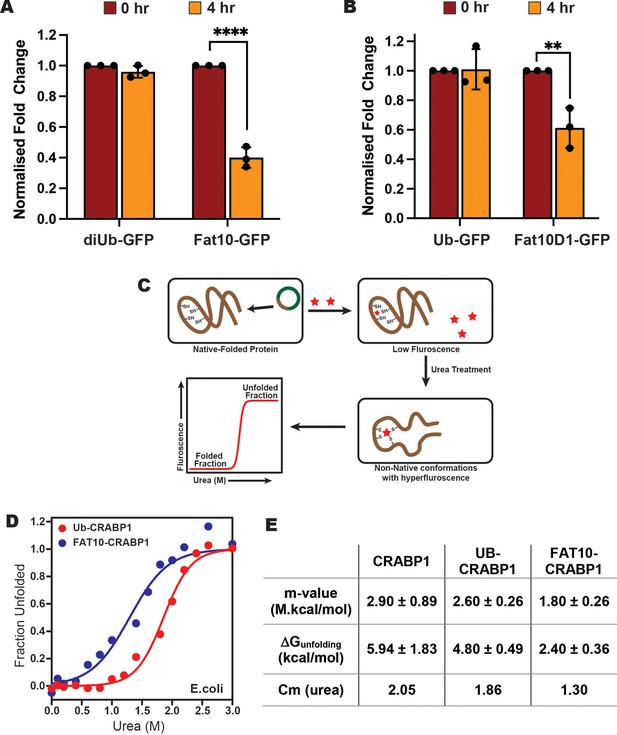

(A) Comparison of diUb-GFP and Fat10-GFP levels post 4 hr treatment with Cycloheximide (CHX) in HEK293T cells (n=3, p <0.0001; 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). (B) Comparison of monoUb-GFP and Fat10D1-GFP levels post 4 hr treatment with Cycloheximide (CHX) in HEK293T cells (n=3, p = 0.0023; 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). (C) The schematic for studying the substrate stability in a heterologous cellular system is provided, where the CRABP1 protein, capable of binding FIAsH-EDT2 dye, was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells as a substrate. The folded protein quenches the dye, while the unfolded protein releases the quenching. The protocol enables the study of protein unfolding under cellular conditions. (D) The cells were treated with different urea concentrations, and the dye fluorescence was measured. The fluorescent signals of Ub-CRABP1 and Fat10-CRABP1 were normalized to plot their denaturation curves against urea concentration. (E) Thermodynamic parameters of CRABP1 in cellular conditions when covalently bound to ubiquitin and Fat10, respectively.

-

Figure 5—source data 1

Original file for the western blot analysis in Figure 5A and B, Figure 5—figure supplement 1A and B (anti-FLAG, anti-actin).

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/91122/elife-91122-fig5-data1-v2.zip

Substrate degradation and unfolding by FAT10 min cells.

(A) In vivo degradation of transiently expressed diUb-GFP after cycloheximide treatment over different time points and immunoprobed with Flag antibody. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (B) In-vivo degradation of transiently expressed FAT10D1-eGFP and Ub-eGFP immunoprobed similar to (A) with β-Actin and Tubulin as loading control. FAT10D1-eGFP after cycloheximide treatment over different time points. Tubulin is used as the loading control. (C) The in vivo fluorescence signal of free-CRABP1, (D) Ub-CRABP1, and (E) Fat10-CRABP1 when cells were incubated without or with 3 M urea. (F) E. coli cells expressing CRABP1 were treated with different urea concentrations, and the dye fluorescence was measured. The fluorescent signals CRABP1 was normalized to plot its denaturation curves against urea concentration.

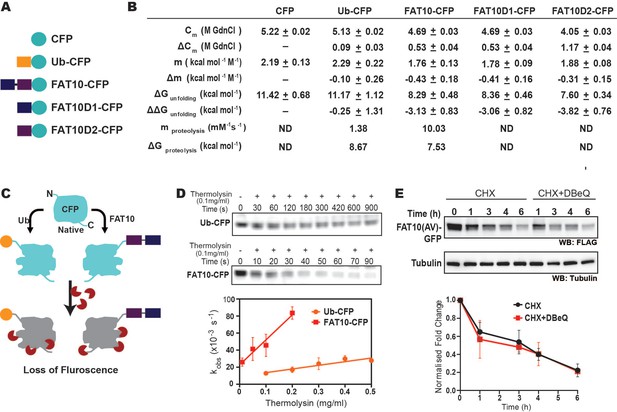

The destabilization effect of Fat10 was investigated using CFP as a substrate.

(A) CFP is fused at the C-terminal end of Ub, Fat10, Fat10D1, and FAT0D2. (B) The thermodynamic and proteolysis parameters of CFP in the fusions given in A were studied. These parameters are provided here. (C) The schematic of the native state proteolytic cleavage of Ub-CFP and Fat10-CFP is provided. The cleavage reactions were carried out using thermolysin. (D) Representative in-gel fluorescence image for native-state proteolysis of Ub-CFP and Fat10-CFP at 0.1 mg ml–1 thermolysin is provided. The rate of proteolysis (kobs) is plotted for Ub-CFP and Fat10-CFP against different thermolysin concentrations. Error bars denote the standard deviation of the replicates (n=3). (E) Degradation of Fat10-GFP in HEK293T cells after cycloheximide treatment without/with p97 inhibitor (DBeQ). Tubulin is used as the loading control. The quantified level of FLAG-Fat10-GFP without/with inhibitor is plotted against time (for n=3).

-

Figure 6—source data 1

Original Gels of Ub-CFP and Fat10-CFP corresponding to Figure 6D and Figure 6—figure supplement 1.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/91122/elife-91122-fig6-data1-v2.zip

-

Figure 6—source data 2

Original file for the western blot analysis in Figure 6E (anti-FLAG, anti-actin).

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/91122/elife-91122-fig6-data2-v2.zip

The effect of ubiquitin, Fat10 and its domains on the thermodynamic stability and proteolysis of CFP.

(A) GdnCl melt curves of CFP, Ub-CFP, and Fat10-CFP where only CFP was probed using its fluorescence signal. The fluorescence values were normalized and plotted against GdnCl concentration. (B) Similarly, the GdnCl melt curve for Fat10D1-CFP and Fat10D2-CFP was plotted. The CFP melt curve in (A) is repeated here for comparison. (C) In-gel fluorescence image for native-state proteolysis of Ub-CFP treated with 0.2 mg ml-1, 0.3 mg ml-1, 0.4 mg ml-1and 0.5 mg ml-1 of Thermolysin. (D) In-gel fluorescence image for native-state proteolysis of Fat10-CFP treated with 0.01 mg ml-1, 0.05 mg ml-1, and 0.2 mg ml-1 of Thermolysin. The normalized intensity of in-gel fluorescence of CFP for 0.1 mg/ml thermolysin treatment is plotted against time for (E) Ub-CFP and (F) Fat10-CFP.

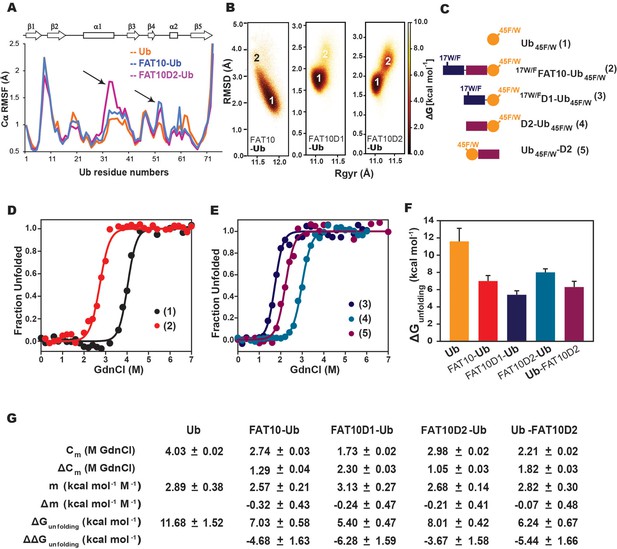

Simulations and melting experiments studied the effect of Fat10 on a model substrate ubiquitin.

(A) Comparing Cα RMSF values of ubiquitin in monoubiquitin, Fat10-Ub, Fat10D1-Ub and Fat10D2-Ub. Black arrows denote regions with higher values in Fat10-conjugated ubiquitin than monoubiquitin. (B) The free energy landscape of Ub in Fat10-Ub, Fat10D1-Ub and Fat10D2-Ub are plotted as a function of RMSD and radius of gyration (Rgyr) obtained from simulations across three replicas (3x2.5 μs) performed at 300 K. (C) Ubiquitin varieties used in this study where, Ub45F/W is covalently conjugated at the C-terminus of 17W/FFat10, 17W/FFat10D1, and Fat10D2. Ub45F/W was also fused at the N-terminus of Fat10D2. (D) GdnCl melt curves of Ub and Fat10-Ub are shown. The tryptophan fluorescence signals of Ub45F/W were normalized and plotted against the GdnCl concentration. (E) GdnCl melt curves were plotted for Fat10D1-Ub, Fat10D2-Ub, and Ub-Fat10D2. (F) The free energy of unfolding ubiquitin in free form and covalently bound to Fat10 domains is plotted. (G) A table with details of thermodynamic parameters of Ub in free and bound forms is shown.

Molecular dynamics of the substrate ubiquitin when conjugated to the Fat10 domains.

(A) Simulations of monoubiquitin (Ub) and diubiquitin (Ub2), Fat10D1-Ub, and Fat10D2-Ub were performed at 450 K. The fraction of native contacts is defined as (α) and plotted against the time for ubiquitin and the proximal unit in di-ubiquitin Ub2 (D2). (B) α is plotted for ubiquitin in the Fat10D1-Ub, Ub in Fat10D2-Ub, and monoUb. (C) The fraction of native backbone hydrogen bonds in the beta-sheet β1 to β5 is defined as (η) and plotted against the time for ubiquitin and the proximal unit in di-ubiquitin Ub2 (D2). (D) is the same as (C), plotted for ubiquitin in the Fat10D1-Ub, ubiquitin in Fat10D2-Ub, and monoUb.

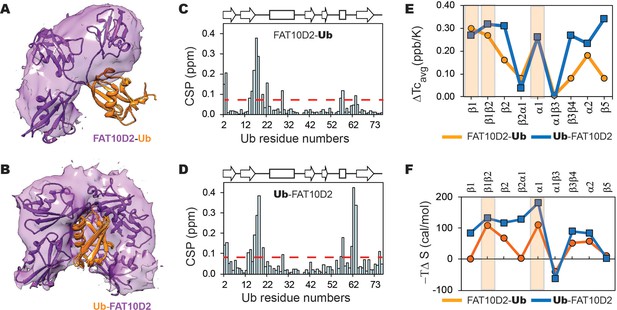

The changes in a model substrate ubiquitin, when conjugated to Fat10D2 domain is studied by MD simulations and NMR.

The occupancy of the D2 domain around Ub in the simulations is shown as a purple surface for (A) Fat10D2-Ub and (B) Ub-Fat10D2. A few structures from the simulation are superimposed and shown. The chemical shift perturbations observed in ubiquitin when conjugated to Fat10D2 domain is plotted for (C) Fat10D2-Ub and (D) Ub-Fat10D2. (E) The difference in mean temperature coefficients between Fat10D2-Ub and free Ub is plotted for the various Ubiquitin segments. The orange line is ΔTcavg = Tc(Ub) avg - Tc(Fat10D2-Ub) avg. The blue line is the same for Ub-Fat10D2, where ΔTcavg = Tc(Ub)avg - Tc(Ub-Fat10D2)avg. A light orange box highlights the regions with high ΔTcavg in Fat10D2-Ub. Ub-Fat10D2 has additional regions with ΔTcavg values. (F) The difference in conformational entropy -TΔS of ubiquitin between free Ub and Fat10D2-Ub, where ΔS=SUb – SFat10D2-Ub, was averaged for the various secondary structures and loops (orange). The same was plotted for Ub-Fat10D2 in blue. A light orange box highlights the regions with high -TΔS in Fat10D2-Ub.

Inter-domain interactions between FAT10 and Ub studied by molecular dynamics simulations.

(A) The number of intermolecular contacts (within 4.5 Å) per μsec between Fat10 and substrate ubiquitin in the Fat10-Ub conjugate detected in the MD simulation. The same is calculated for the conjugate of the D2 domain and ubiquitin in the Fat10D2-Ub and Ub-Fat10D2 conjugates. (B) The intermolecular contacts between Fat10 and ubiquitin are plotted as a contact map. Blue rectangles mark the contact with significant occupancies. (C) The difference between long-range (i, i+5) intra-ubiquitin contacts in free ubiquitin and Fat10-ubiquitin conjugate is plotted as a contact map. Positive values indicate ubiquitin contacts disrupted in the Fat10-Ub conjugate, and negative values indicate new ubiquitin contacts formed in the Fat10-Ub conjugate.

The difference in inter-domain long range contacts between FAT10-Ub and diubiquitin studied by molecular dynamics simulations.

(A) The difference of long-range (i, i+5) intra-ubiquitin contacts in diubiquitin and Fat10-ubiquitin conjugates are given as a table. The positive difference value indicates contacts present in diubiquitin but disrupted in Fat10-ubiquitin. (B) The difference between long-range intra-ubiquitin contacts in diubiquitin and Fat10-ubiquitin conjugate is plotted as a ubiquitin contact map. Positive values indicate contacts disrupted in the Fat10-ubiquitin conjugate but present in diubiquitin. Negative values indicate new contacts formed in Fat10-ubiquitin but absent in diubiquitin. Blue rectangles indicate regions with severely disrupted contacts in Fat10-ubiquitin. (C) and (D) The intermolecular contacts are plotted between ubiquitin and D2 domain for Fat10D2-Ub and Ub-Fat10D2, respectively. (E) and (F) The difference of intra-ubiquitin contacts is plotted for Fat10D2-ubiquitin and ubiquitin-Fat10D2 in, respectively. Positive values indicate contacts disrupted in the Fat10-ubiquitin conjugates but present in diubiquitin. Negative values indicate the inverse. Blue rectangles indicate regions with severely disrupted contacts in the Fat10D2 conjugates.

2D-HSQC spectrum with assigned peaks of ubiquitin residues in each of the chimeric constructs: (A) Fat10D2-Ub and (B) Ub-Fat10D2.

(C) The averaged Tc is plotted for the various regions in ubiquitin for the free ubiquitin, and ubiquitin conjugated to Fat10 domains.

Changes in the ubiquitin backbone dynamics by conjugation to Fat10 domains.

The measured values of longitudinal relaxation rates (R1), transverse relaxation rates (R2), Nuclear Overhauser Enhancement (hetNOE), and order parameter (S2) for ubiquitin residues are shown in the case of free (A) Fat10D2-Ub and (B) Ub-Fat10D2. The Ub secondary structure elements are provided on the top panel.

Thermodynamic Coupling in FAT10-substrate conjugate system.

(A) The free energy landscape of Fat10D2 in the free form, Fat10D2-Ub, and Ub-Fat10D2 is plotted as a function of RMSD and radius of gyration (Rgyr), which was obtained from simulations across three replicas (3x2.5 μs) performed at 300 K. (B) Simulations of free Fat10D2 and Ub-Fat10D2 were performed at 450 K. The fraction of native contacts is defined as (α) and plotted against time. The data is averaged over ten replicas. (C) Similar to (B) plotted for Ub-Fat10D2 and Fat10D2-Ub. The Ub-Fat10D2 data are replotted here as a control.

Tables

| Reagent type (species) or resource | Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain, strain background (E. coli) | DH5α | Invitrogen | Cat# 18265017 | Plasmid DNA ampilification |

| Strain, strain background (E. coli) | BL21(DE3) | Invitrogen | Cat# EC0114 | Protein Expression |

| Cell line (Homo-sapiens) | HEK293T | NCBS, India | Gift from Dr. Apurva Sarin Lab, NCBS | |

| Antibody | Anti-Flag (Mouse monoclonal) | SIGMA | Cat# F3165 | WB (1:10,000) |

| Antibody | Anti-Tubulin (Mouse monoclonal) | SIGMA | Cat# T6199 | WB (1: 3000) |

| Antibody | Anti-β Actin (Mouse monoclonal) | Santa Cruz | Cat# sc47778 | WB (1: 5000) |

| Antibody | HRP-conjugated anti-mouse (goat polyclonal) | SIGMA | Cat# 12–349 | WB (1:10,000) |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | Fat10 (pET3a plasmid) | Life Technologies | C7A, C9A, C160A, and C162A (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | Fat10D1 (1-83aa; pET3a plasmid) | This paper | C7A, C9A, (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | Fat10D2 (84-165aa; pET14b plasmid) | This paper | C160A, and C162A (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | CFP (pET3a plasmid) | This paper | (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | Ub-CFP (pET3a plasmid) | This paper | (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | Fat10-CFP (pET3a plasmid) | This paper | (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | Fat10D1-CFP (pET3a plasmid) | This paper | (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | Fat10D2-CFP (pET14b plasmid) | This paper | (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | Fat10-Ub (pET3a plasmid) | This paper | (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | Fat10D1-Ub (pET3a plasmid) | This paper | (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | Ub-Fat10D2 (pET3a plasmid) | This paper | (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | Fat10D2-Ub (pGEX6P1 plasmid) | This paper | (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | Ub (pET3a plasmid) | This paper | F45W (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | W17FFat10-UbF45W (pET3a plasmid) | This paper | W17F in Fat10; F45W in Ub (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | W17FFat10D1-UbF45W (pET3a plasmid) | This paper | W17F in Fat10D1; F45W in Ub (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | Fat10D2- UbF45W (pGEX6P1 plasmid) | This paper | F45W in Ub (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | UbF45W -Fat10D2 (pET3a plasmid) | This paper | F45W in Ub (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | Ubm1(pET3a plasmid) | This paper | E34R (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | Ubm2 (pET3a plasmid) | This paper | E34R, K27D (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | CRABP1 (pET3a plasmid) | Life Technologies | (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | Ub-CRABP1 (pET3a plasmid) | This paper | (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | Fat10-CRABP1 (pET3a plasmid) | This paper | (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | 3XFLAG-wtFat10AV (pcDNA3.1 plasmid) | Life Technologies | ||

| Recombinant DNA reagent | 3XFLAG-Fat10D1 (pcDNA3.1 plasmid) | This paper | (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | 3XFLAG-Fat10D2-AV (pcDNA3.1 plasmid) | This paper | (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | 3XUb-K0AV (pcDNA3.1 plasmid) | This paper | (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | 3XUb-K0GV (pcDNA3.1 plasmid) | Life Technologies | ||

| Recombinant DNA reagent | 1XFLAG UbGV-GFP (pcDNA3.1 plasmid) | This paper | (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | 1XFLAG diUbGV-GFP (pcDNA3.1 plasmid) | This paper | (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | 1XFLAG FAT10AV-GFP (pcDNA3.1 plasmid) | This paper | (See Materials and Methods, Cloning section) | |

| Recombinant DNA reagent | 1XFLAG FAT10D1-GFP (pcDNA3.1 plasmid) | Life Technologies | ||

| Commercial assay or kit | Plasmid DNA purification kit | Promega | Cat# A4160 | Plasmid DNA isolation |

| Commercial assay or kit | PCR clean up kit | Promega | Cat# A9282 | PCR clean up |

| Chemical compound, drug | CHX; MG132 | SIGMA | ||

| Chemical compound, drug | N15-Ammonium Chloride; C13- D-Glucose | Cambridge Isotope Laboratory., Inc | Cat No# NLM-467; CLM-1396 | Isotope Enrichment media |

| Chemical compound, drug | Protease inhibitor Cocktail | SIGMA | Cat# 11873580001 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | DBeQ | MedChem express | Cat# HY-15945 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | FlAsH-EDT2 | Cayman Chemicals | Cat# 20704 | |

| Chemical compound, drug | ECL reagent | Biorad | Cat# 1705060 | For developing PVDF membrane |

| Chemical compound, drug | BCA kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 23225 | For total protein estimation |

| Software, algorithm | NMR Pipe; Sparky; GraphPad Prism; SIGMA Plot; ImageJ; AMBER | Delaglio et al., 1995; Lee et al., 2015; Schmidtke et al., 2014 |