Design of the HPV-automated visual evaluation (PAVE) study: Validating a novel cervical screening strategy

Figures

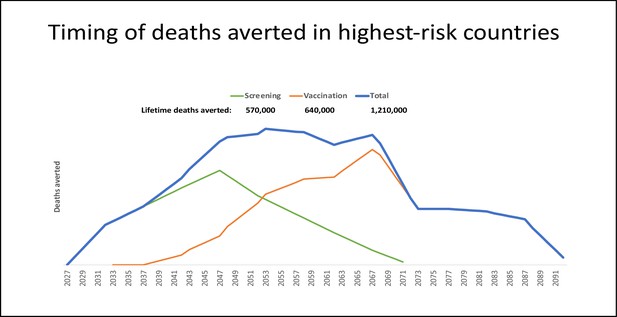

Timing and deaths averted with one-time prevention campaigns: vaccination only, screening only, or both.

Projection of the relative timing of health benefits, measured as deaths averted, accrued by vaccination and/or screening applied through one-time campaigns. Three scenarios were examined: (1) a one-time screening campaign providing effective management for approximately 25% of 30- to 49-year-old women in 2027 (i.e. 20 birth cohorts) (green line); (2) vaccinating 90% of 9- to 14-year-old girls in 2027 (i.e. six birth cohorts) with a bivalent HPV16/18 vaccination (orange line); and (3) both a screening campaign and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination for respective birth cohorts in 2027 (blue line). We considered cervical cancer deaths averted over the lifetime of cohorts subject to the intervention, and conservatively assumed that deaths averted due to screening would only occur after age 50, to account for prevalent cancers. Projections were developed for the ~65 low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) with age-standardized cervical cancer incidence greater than 10 per 100,000 women (Perkins et al., 2023). For each country, we assumed that, in the absence of any intervention, the number of cervical cancer deaths for each 5 year age group would apply each year for the lifetime of the selected birth cohorts (Perkins et al., 2023). We conservatively and crudely assumed that screening and management would avert 25% of cervical cancer deaths (equivalent to screening uptake of 40% of eligible women, with 62.5% of screen-positive women receiving appropriate management) beginning at age 50 years. For vaccination cohorts, we assumed that a bivalent HPV16/18 vaccine (i.e. against the genotypes responsible for 70% of cervical cancers) with 90% uptake would avert 63% of cervical cancer deaths. While data on the costs of implementing novel screening strategies and single-dose HPV vaccination for female adolescents are forthcoming from the HPV-automated visual evaluation (PAVE) consortium and single-dose vaccination studies, we crudely assumed a single vaccine dose cost US$4.5031 with an average financial delivery cost per dose (i.e. per fully immunized girl) of US$7 (Akumbom et al., 2022). We assumed a bundled financial cost per woman screened of US$15, including a low-cost rapid HPV genotyping assay with triage and treatment of screen-positive women. According to our projections, the number of interventions needed to avert one cervical cancer death was similar for HPV vaccination and screening (i.e. 278 for HPV vaccination; 293 for screening). A one-time screening campaign for women aged 30–49 years in the selected countries yielded a financial cost of ~US$2.5 billion to avert ~570,000 deaths, or US$4,400 per death averted. On a similar order of magnitude, a one-time single-dose bivalent HPV vaccination campaign of girls aged 9–14 years in the same countries would cost ~US$2.0 billion and avert ~640,000 deaths, or US$3,200 per death averted. Of note, these ballpark estimates are undiscounted and do not account for cancer treatment cost offsets. We also did not consider demographic changes over the lifetime of intervention cohorts, nor did we consider the indirect benefits of vaccination or prevention of other HPV-related cancers.

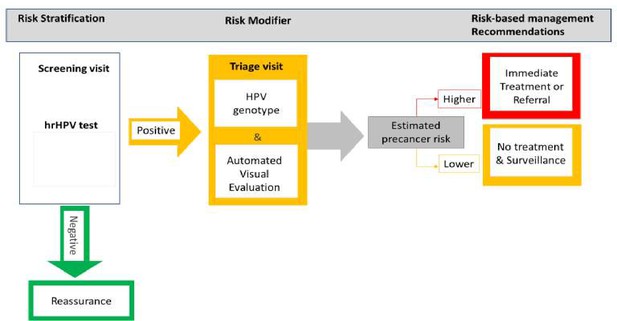

Risk-based HPV-automated visual evaluation (PAVE) screen-triage-treat strategy provides risk stratification to assist in the management of screening participants.

hrHPV: refers to those human papillomavirus (HPV) types considered as having a high potential capacity to induce cervical cancer when the infection is persistent over time. It includes HPV16, 18, 45, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58, 39, 51, 56, 59, and 68.

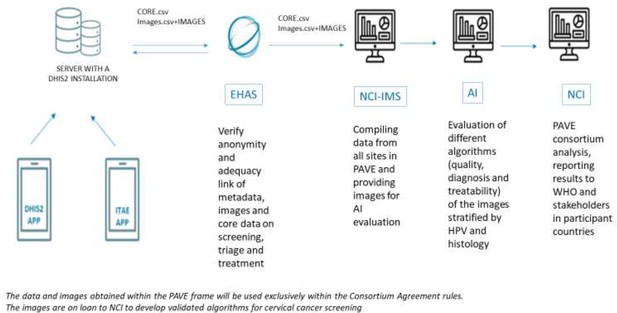

Flowchart of data sharing in the HPV-automated visual evaluation (PAVE) study sites using the DHIS2 during the efficacy phase.

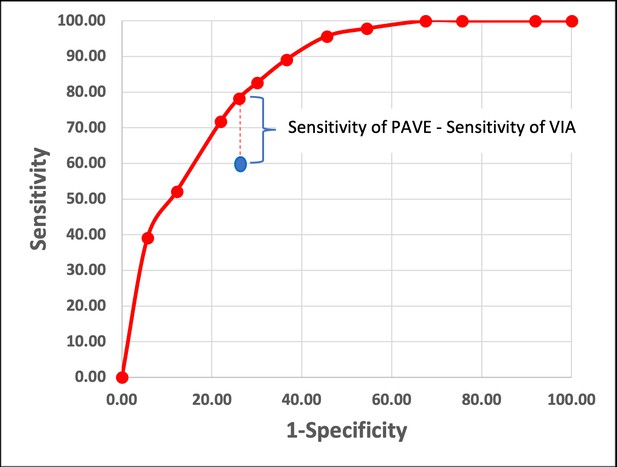

Theoretical approach to compare the PAVE strategy (which is HPV and AVE combined strategy. in red) and the standard of care (SOC) screening and triage outcome (which commonly is VIA, in blue).

This figure represents a hypothetical example showing how testing for HPV and using AVE as triage (PAVE) and SOC will be compared. Under a specific specificity value (which will be determined by the SOC), we will compare the difference between the sensitivities of PAVE and SOC. In this example, we had three categories for human papillomavirus (HPV) genotype groups and three categories for automated visual evaluation (AVE) (normal-indeterminate-precancer/cancer), and in total nine PAVE categories. We estimate that about half of the CIN3 + cases will be positive for HPV16, and about 10–15% will be HPV18/45 positive, and that the remaining two other channels will have a 20% prevalence within cases.

Tables

Site-specific primary triage and treatment protocols Biopsy and treatment protocols.

| Site | Primary Screening Test | Triage method | Staff taking biopsies | Biopsy Instrument | Treatment threshold | Primary Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dominican Republic | ScreenFire HPV, Cytology | Colposcopy | Gynecologists | Biopsy forceps | CIN2+ +biopsy | Ablation or LLETZ |

| Malawi | ScreenFire HPV | VIA | Nurses | Softbrush | VIA-positive | Ablation or LLETZ |

| Nigeria | ScreenFire HPV | Colposcopy | General Doctors, Gynecologists, GYN oncologists | Biopsy forceps | HPV-positive | Ablation or LLETZ |

| Brazil | ScreenFire HPV | Conventional cytology, liquid-based cytology, and colposcopy | Gynecologists | Biopsy forceps | CIN2 + biopsy or high-grade colpo impression | LLETZ |

| Cambodia | ScreenFire HPV | Colposcopy (mobile colposcope) | Nurse midwives, General Doctors, Gynecologists | Softbrush | VIA-positive or HPV16,18/45 positive | Ablation or LLETZ |

| Eswatini | ScreenFire HPV & VIA | VIA | Nurse midwives | Softbrush | VIA-positive | Ablation |

| El Salvador | ScreenFire HPV, Cytology, CareHPV | Colposcopy and VAT | General Doctors | Biopsy forceps | HPV-positive | Ablation |

| Tanzania | ScreenFire HPV | VIA | Gynecologists, nurses, nurse midwives | Biopsy forceps, Softbrush | VIA-positive | Ablation |

| Honduras | ScreenFire HPV | Colposcopy and VAT | Nurse midwives, General Doctors, | Biopsy forceps | VIA-positive | Ablation |

HPV-AVE risk strata.

| AVE Risk Classification | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HPV risk group | Precancer+ | Indeterminate | Normal |

| HPV16 | Highest | High | High |

| HPV18/45 | High | High | High |

| HPV31/33/35/52/58 | High | Medium | Medium |

| HPV39/51/56/59/68 | High | Medium | Low |

| Negative | Lowest | ||

Risk strata for participants with an HPV-positive women and visual Standard of Care (SOC) as the triage (i.e. VIA, colposcopy) test.

| SOC classification* | ||

|---|---|---|

| HPV test result | Positive/High grade | Normal |

| Positive | High | Low |

| Negative | Lowest | |

-

Note: Participants with a negative test for HPV will not have a VIA nor colposcopy assessment. see Table 1 for SOC at individual PAVE sites.