Causal evidence for a domain-specific role of left superior frontal sulcus in human perceptual decision-making

Figures

Behavioural food choice paradigm, theta-burst stimulation protocol, and behavioural regressions.

(A) Example of decision stage. Participants were cued in advance about the type of decision required. Perceptual decisions required participants to choose the food item with the largest size while value-based decisions required participants to choose the food item they preferred to consume at the end of the experiment. Participants alternated between blocks of perceptual (blue) or value-based (red) choice trials (7–9 trials per task-block). (B) Logistic regression results show that the larger the evidence strength, the more likely decision-makers will respond accurately. Choice accuracy is only related to the evidence that is currently task-relevant (size difference [SD] for perceptual or value difference [VD] for value-based choice), not to the task-irrelevant evidence (RT is reaction time of current choice). (C) Similarly, our linear regressions show that RTs are negatively associated only with the task-relevant evidence (and lower for perceptual choices overall, captured by regressor CH (1 = perceptual, 0 = value-based)). Consistent with previous findings, the results in (B) and (C) confirm that our paradigm can distinguish and compare evidence processing for matched perceptual- and value-based decisions. Error bars in (B) and (C) represent the 95% confidence interval range of the estimated effect sizes. *, **, and ***. (D) Theta-burst stimulation protocol. After the fourth pre-TMS run, participants received continuous theta-burst stimulation (cTBS) over the left superior frontal sulcus (SFS) region of interest (ROI) (area encircled and coloured blue). cTBS consisted of 200 trains of 600 pulses of 5 Hz frequency for 50 s.

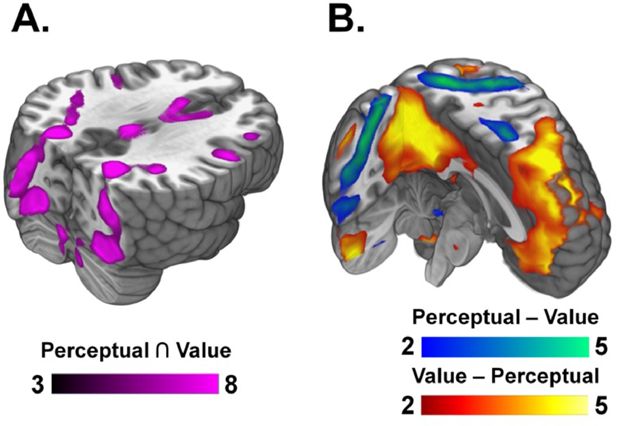

Domain-general and domain-specific regions involved in perceptual- and value-based decisions.

(A) Domain-general regions. We found domain-general regions shared by both perceptual decision-making (PDM) and value-based decision-making (VDM), such as areas in the visual stream along the fusiform gyrus, cerebellar areas including the brainstem and motor areas such as premotor cortex and SMA (conjunction a , cluster-corrected, see Supplementary file 1 for the complete list of regions). (B) Domain-specific regions. Comparing average decision-related activity between perceptual- and value-based decisions revealed distinct brain activations. Blue-green represents significant neural activity for PDM > VDM decisions while red-yellow represents significant activity for VDM > PDM (see Supplementary file 2). Among the active regions in the VDM > PDM contrast are the orbitofrontal cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex, and the medial prefrontal cortex, while the regions active in the PDM > VDM contrast include the frontal eye fields, the intraparietal sulcus, and premotor cortex.

Study hypotheses.

Scenario 1: left superior frontal sulcus (SFS) is causally involved in evidence accumulation. Theta-burst induced inhibition of left SFS should lead to reduced evidence accumulation (A), expressed as lower accuracy (A, second row, left), slowing of RTs (A, second row, right), and a reduction of DDM drift rate (B, right) without any effect on the boundary parameter (B, left). Since the neural activity devoted to evidence accumulation (area under the curve) should increase (C, left), we would expect higher BOLD signal in this case (C, right). Scenario 2: left SFS is causally involved in setting the choice criterion. Theta-burst induced inhibition of left SFS should lead to a lower choice criterion (D), expressed as lower choice accuracy (D, second row, left), faster RTs (D, second row, right), and a reduced DDM decision boundary parameter (E, left) without any effect on the DDM drift rate (E, right). At the neural level, we should observe reduced BOLD activity due to the lower amount of evidence processed by the neurons (F, right), and reflected by the smaller area under the evidence accumulation curve when it reaches the lower boundary (F, left).

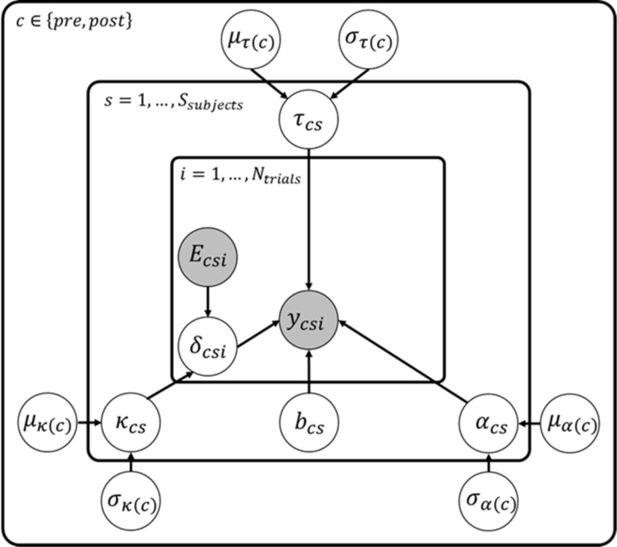

Hierarchical Bayesian DDM.

Graphical representation of the hierarchical Bayesian DDM fitted to choice data. Clear circles represent latent variables while filled circles represent observed variables, that is, choice data, , and evidence, , for each trial . Choice data contain both accuracy and response times. The following equations show the distributions assumed for each of the latent variables in the model:

Trial-by-trial, i

Subject, c

Observable variables

For the hyper-group or latent parameters at the highest level of the hierarchy (represented by and ), we assumed flat uniform priors. The distributions for the following are:

The following model parameters are: 𝛼 (decision threshold), 𝜅 (drift rate parameter scaling the evidence, 𝐸), and 𝜏 (non-decision times).

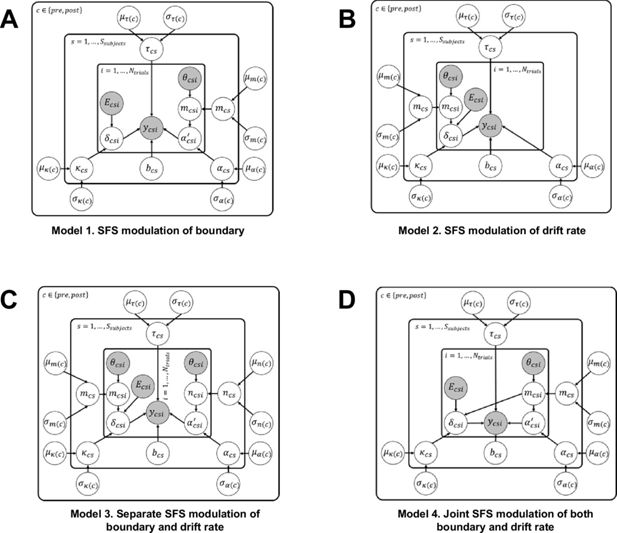

Neural-hierarchical drift-diffusion model (HDDM) alternatives.

To test whether the left superior frontal sulcus (SFS) is mechanistically involved in the latent decision-relevant processes, we included trial-by-trial left SFS neural betas as an input to our hierarchical drift diffusion model. We compared our neural HDDM with the HDDM without neural inputs. We additively incorporated trialwise left SFS and used a scale parameter, , to account for its modulatory effects. The following equations show the distributions assumed for each of the latent variables in the model:

Trial-by-trial, i

Model 1:

Model 2:

Model 3:

Model 4:

Subject, c

Observable variables

.

Particularly, (A) Model 1 incorporates trialwise left SFS betas into the decision boundary. (B) Model 2 incorporates trialwise left SFS betas into the drift rate. (C) Model 3 includes trial-by-trial betas in both decision thresholds and the drift rate, but with separate scale parameters. (D) Model 4 includes trial-by-trial betas in both latent parameters but with one common scale parameter.

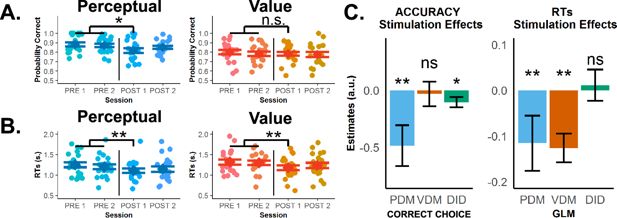

Theta-burst stimulation over the left superior frontal sulcus (SFS) affects choice behaviour and selectively lowers the decision boundary for perceptual but not value-based choices.

(A) Choice accuracies/consistencies and (B) response times (RTs) for perceptual- (blue) and value-based (orange) decisions for different evidence levels during pre-cTBS (dark) and post-cTBS (light) stimulation periods. Error bars in (A) and (B) represent SEM. Consistent with previous findings, stronger evidence leads to more accurate choices and faster RTs in both types of decisions. Importantly, theta-burst stimulation significantly lowered choice accuracy selectively for perceptual, not value-based decisions (negative main stimulation effect for perceptual decisions and negative stimulation × task interaction; Figure 3—figure supplement 1C and see also Figure 3—figure supplement 1A for changes in choice accuracy across runs). Additionally, theta-burst stimulation also significantly lowered RTs in both choice types (negative main stimulation effect; Figure 3—figure supplement 1C and see also Figure 3—figure supplement 1B for changes in RTs across runs). (C) Theta-burst stimulation selectively decreased the decision boundary in perceptual decisions only (difference between estimated posterior population distributions; see Methods and Figure 3—figure supplement 2A for a detailed post hoc analysis). All the other parameters, particularly (D) the drift rate (see also Figure 3—figure supplement 2B for post hoc analysis), remain unaffected by stimulation. Error bars in (C) and (D) represent the 95% confidence interval range of the posterior estimates of the DDM parameters. *, **, and ***.

Theta-burst stimulation in left superior frontal sulcus (SFS) selectively lowers choice accuracy for perceptual decisions, but RTs become faster after stimulation in both choice types.

(A) Observed accuracies and (B) mean RTs of individual participants for perceptual decision-making, PDM (blue) and value-based decision-making, VDM (orange-yellow) across pre- and post-stimulation runs. Error bars in (A) and (B) represent SEM. Theta-burst stimulation significantly lowered choice accuracy for PDM, not VDM, especially during the first post-stimulation run. On the other hand, RTs sped up in both perceptual- and value-based decisions. Unsurprisingly, both accuracy levels and RTs began to recover during the second post-stimulation run for PDM. (C) In our regression analysis, comparing the pre–post PDM difference in accuracy with the pre–post VDM difference confirms the significant effect of theta-burst stimulation in selectively lowering choice accuracy (left panel) for perceptual decisions (green, negative stimulation × task interaction). In contrast, the effect is nonspecific for RTs (right panel). Error bars in (C) represent the 95% confidence interval range of the estimated effect sizes. *, **, and ***.

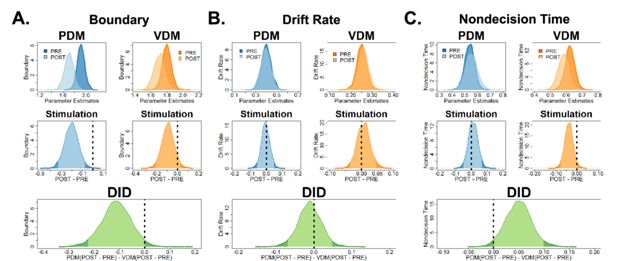

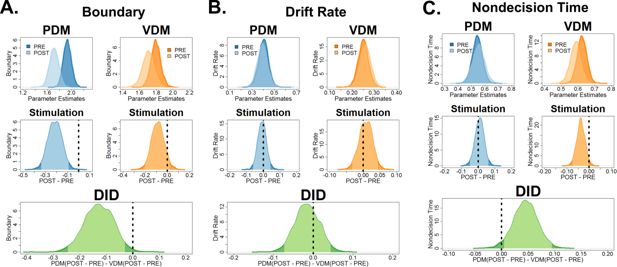

Theta-burst stimulation in the left superior frontal sulcus (SFS) reduced decision boundary for perceptual decisions.

(A) Bayesian poster probability distributions of DDM parameters (top row of panel) before (dark colour) and after stimulation (light colour) for perceptual- (blue) and value-based (yellow-orange) decisions. Theta-burst stimulation has lowered the decision boundary for perceptual decision (PDM) not value-based decisions (VDM). (B) Drift rate was unaffected after theta-burst stimulation, while (C) non-decision times decreased in VDM, not PDM. To test for a stimulation effect, post hoc tests (middle row of panel) compare pre- and post-stimulation DDM parameters for each type of decision. The highest density interval (HDI) spans within the 95% interval (light colour) and represents a null effect. We can statistically confirm the effect of theta-burst stimulation if the decision criterion (dashed vertical line) is outside the 95% HDI (dark colour). In our post hoc analysis, only the decision boundary during PDM had its criterion outside the 95% HDI and marginally for non-decision times. However, the criterion for the drift rate was well within the 95% HDI. Hence, these results show that theta-burst stimulation significantly decreased the decision boundary for PDM and non-decision times for VDM. To test whether stimulation is selective for only one decision domain, our post hoc test (green, bottom row) compared the pre–post PDM differences with the pre–post VDM differences. In this analysis, both the criterion for the decision boundary and non-decision times were outside the 95% HDI.

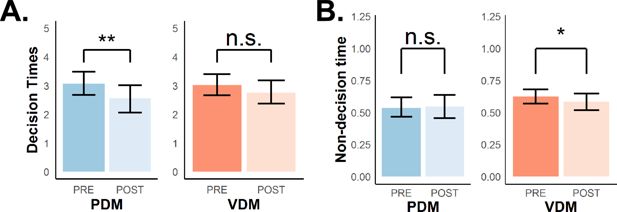

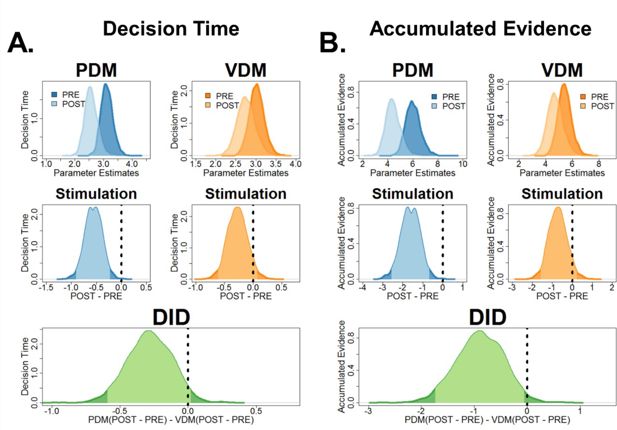

The DDM disentangles the latent decision-relevant and decision-irrelevant processes observed with faster RTs.

(A) We derived a measure of decision times (DT, upper row) and (B) estimated non-decision times (nDT, lower row) from the DDM. We derived and estimated these parameters to test whether faster RTs in both perceptual decision-making (PDM) and value-based decision-making (VDM) after stimulation are due to the same or different latent processes in the DDM, and whether these processes are decision-relevant or not. These results show that different latent processes are driving faster RTs for PDM and VDM. Theta-burst stimulation significantly lowered DT in perceptual (blue), not value-based (orange) decisions. In contrast, stimulation marginally but selectively decreased nDT for VDM, not PDM. A post hoc analysis confirms domain-specificity of lower nDT for VDM (Figure 3—figure supplement 2C). Taken together, these results explain what processes underlie observed faster RTs in both decisions. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval range of the posterior estimates of the DDM parameters. *, **, and ***.

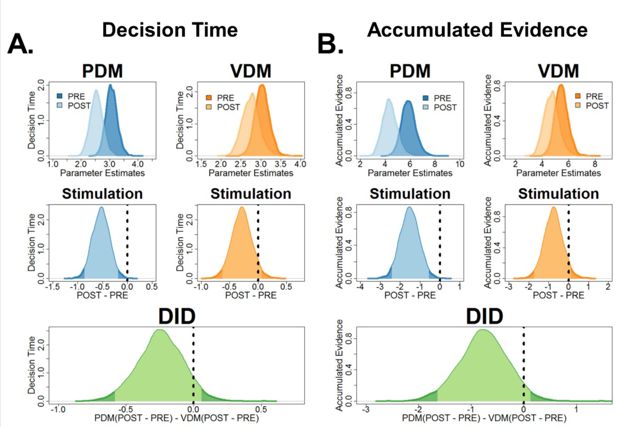

Simulations of fitted model: theta-burst stimulation in the left superior frontal sulcus (SFS) reduced decision times and accumulated evidence.

(A) Bayesian posterior probability distributions (top row) of decision times and (B) accumulated evidence before (dark colour) and after (light colour) for perceptual (blue) and value-based (yellow-orange) decisions. Post hoc tests (middle row) comparing pre- and post-stimulation revealed that theta-burst stimulation significantly decreased both decision times and accumulated evidence for perceptual, not value-based decisions. However, post hoc tests comparing the pre–post perceptual decision-making (PDM) differences with the pre–post VDM differences showed that the criterion is marginally inside the 95% HDI.

Neural representation of accumulated evidence in the left superior frontal sulcus (SFS) is disrupted after theta-burst stimulation and is linked with behaviour and neural computation.

(A) Left panel: Accumulated-evidence (AE) simulation derived from the fitted DDM (left panel). Previous studies have illustrated how the accumulation-to-bound process convolved with the haemodynamic response function (HRF) results in BOLD signals; hence, the simulated AE provides a suitable prediction of BOLD responses in brain regions involved in evidence accumulation. Theta-burst stimulation selectively decreased AE for (A) perceptual (blue), not (B) value-based (orange) decisions (see Figure 3—figure supplement 4B for post hoc analysis). We constructed a trialwise measure of accumulated evidence using RTs and evidence strength for our parametric modulator (see Methods). Individual regions of interest (ROIs) extracted from the left SFS representing accumulated evidence across runs (right panels; see Methods) show that consistent with the DDM prediction, theta-burst stimulation selectively decreased BOLD response representing AE in left SFS during perceptual, not value-based decisions. Error bars in the left panels of (A) and (B) represent the 95% confidence interval range of the posterior estimates of the DDM parameters, while error bars in their respective right panels represent SEM. (C) Post–pre contrasts for the trialwise accumulated-evidence regressor show reduced left-SFS BOLD during perceptual decisions (green overlay), with a significantly stronger reduction for perceptual- versus value-based decisions (blue overlay). No reduction is observed for value-based decisions. (D) To test the link between neural and behavioural effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), regression results show that after stimulation, BOLD changes in left SFS are associated with lower choice accuracy (left panel) for perceptual (PDM, blue) (negative left SFS × stimulation interaction) but not value-based choices (VDM, red), with significant differences between the effects on both choice types (difference-in-difference, DID, green, negative left SFS × stimulation × task interaction). On the other hand, cTBA-induced changes in left SFS activity are unrelated to changes in RT (right panel). Error bars in (D) represent the 95% confidence interval range of the estimated effect sizes. *, **, and ***. (E) To test the link between neural activity and DDM computations, we included trialwise beta estimates of left-SFS BOLD signals as inputs to the DDM. Alternative models tested whether trialwise left-SFS (LD) activity modulates the decision boundary () (Model 1), the drift rate (), or a combination of both (Models 3 and 4, see Methods and Figure 2—figure supplement 2 for more details). Model comparisons using the deviance information criterion (DIC, smaller values mean better fits) showed that Model 1 fits the data best, confirming that the left SFS is involved in selectively changing the decision boundary for perceptual decisions.

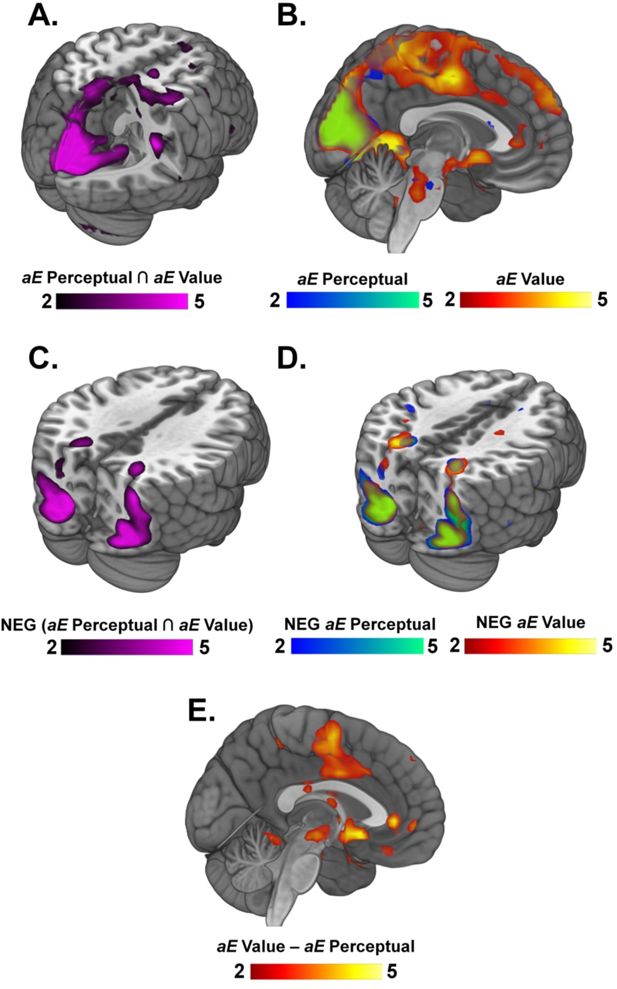

Neural representations of accumulated evidence across the whole brain for PDM and VDM.

(A) Conjunction between areas representing accumulated evidence (aE) during perceptual (PDM) and value-based decisions (VDM) reveals activations in visual and parietal areas, such as the cuneus, postcentral gyrus, and lingual gyrus (see Supplementary file 3). (B) Representations of accumulated evidence for PDM and VDM. Particularly, BOLD responses associated with AE in perceptual decisions are seen in the left superior frontal sulcus (SFS) (see Supplementary file 3). (C) Negative conjunction contrasts shared by both PDM and VDM represent the efficiency of evidence accumulation (i.e., the inverse of accumulated evidence). These contrasts reveal activations in occipital and parietal areas (see Supplementary file 3). Particularly, parietal areas have been previously implicated in the efficiency of accumulating evidence. (D) Negative contrasts for each choice domain reveal activations in parietal and occipital areas (see Supplementary file 4). (E) Contrasts comparing the neural representation of accumulated evidence between value-based and perceptual decisions revealed activations in areas such as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and the nucleus accumbens (see Supplementary file 4).

Reanalysis of latent DDM parameters using the neural-hierarchical drift-diffusion model (HDDM) confirmed the results of lower decision boundary in perceptual decision-making (PDM) and lower non-decision times in value-based decision-making (VDM).

We used the winning neural-HDDM model where the left superior frontal sulcus (SFS) is modulating the decision threshold (Figure 2—figure supplement 2A). (A) Bayesian posterior probability distributions (top row) of all DDM parameters show similar effects with the DDM without neural inputs. Post hoc tests (middle and bottom rows) comparing pre–post PDM differences with pre–post VDM differences show that theta-burst stimulation selectively reduced the decision boundary for perceptual, not value-based decisions. In particular, the criterion is well outside the 95% HDI. (B) The mean drift rate remained unaffected even with our neural-HDDM model (the criterion is within the 95% HDI). (C) Post hoc tests also revealed lower non-decision times specifically for VDM, not PDM after stimulation (the criterion is outside the 95% HDI).

Reanalysis of decision times and accumulated evidence using the neural-hierarchical drift-diffusion model (HDDM) provides improvements in model evidence and clearer statistical inference.

Using the winning neural-HDDM model (Figure 2—figure supplement 2A), we derived measures for (A) decision times and (B) accumulated evidence and tested whether improvements in model evidence reflect improvements in statistical inference. Post hoc tests comparing pre–post perceptual decision-making (PDM) difference revealed a main stimulation effect in both decision times (DT) and AE for PDM (middle row, criteria outside the 95% HDI). Further post hoc analysis (bottom row) comparing the pre–post PDM difference with the pre–post value-based decision-making (VDM) difference shows that decision times are now marginally close to the border of the 95% HDI while accumulated evidence is now outside the 95% HDI.

SFS-TMS (superior frontal sulcus-transcranial magnetic stimulation)-related changes in behaviour and neural computations are accompanied by increased functional coupling between the left SFS and occipital cortex (OCC).

(a) Psychophysiological interaction (PPI) analysis reveals an area in OCC showing increased functional coupling with the left SFS during perceptual choices. (b) Region of interest (ROI) analysis of individual PPI betas shows that aE-related functional coupling between the left SFS and OCC is selectively increased post stimulation during perceptual (left panel) but not value-based decisions (right panel). Error bars in (B) represent SEM. (C) Regression results testing the link between continuous theta-burst stimulation (cTBS) effects on left SFS–OCC functional coupling and behaviour. Increased SFS–OCC coupling is associated with lower choice accuracy (left panel) specifically for perceptual (PDM, blue, negative OCC × stimulation interaction) but not value-based choices (VDM, red). In addition, increased functional coupling is also associated with faster RTs (right panel) for perceptual (blue, negative OCC × stimulation interaction) and slower RTs for value-based choice (red, positive OCC × stimulation interaction). Error bars in (C) represent the 95% confidence interval range of the estimated effect sizes. *, **, and ***.

Posterior-predictive checks: overall accuracy and RT distributions.

Posterior-predictive simulations from the fitted hierarchical drift-diffusion model (HDDM) compared to observed data. Left column: histograms show the simulated distribution of mean accuracy across 3000 posterior draws; the vertical dashed line marks the observed mean accuracy. Right column: observed RT histograms (positive = correct; negative = error) with posterior-predictive density curves overlaid. Panels show (A) PDM versus VDM (pooled over TMS), (B) pre-TMS, and (C) post-TMS. The model reproduces both accuracy and RT patterns in each condition.

Posterior-predictive checks by evidence level.

Similar to Appendix 1—figure 1, but split by evidence levels 1–4 (left-to-right within each row). Rows display: (top) PDM pooled over TMS for (A) choice accuracy and response times (B), (middle) pre-TMS (C, D), and (bottom) post-TMS (E, F); the corresponding three rows for VDM are arranged analogously for pooled (G, H), pre-TMS (I, K) and post-TMS (L, M). Simulations closely match accuracy and RT distributions at each evidence level in both tasks.

Subject-level accuracy fits for PDM.

For each participant, the histogram shows the posterior-predictive distribution of that participant’s mean accuracy from 3000 simulations; the vertical dashed line marks the observed mean accuracy for that participant. The hierarchical drift-diffusion model (HDDM) captures the dispersion of accuracies across individuals in PDM.

Subject-level accuracy fits for VDM.

Same format as Appendix 1—figure 3, for VDM. Posterior-predictive distributions align with observed subject-level accuracies, indicating good recovery of between-subject variability in the value-based task.

Subject-level RT distribution fits for PDM.

For each participant, observed PDM RT histograms (positive = correct; negative = error) are overlaid with posterior-predictive density curves from the hierarchical drift-diffusion model (HDDM). The model reproduces the full shape of individual RT distributions, including correct/error asymmetries.

Subject-level RT distribution fits for VDM.

Same format as Appendix 1—figure 5, for VDM. Posterior-predictive densities closely track the observed RT distributions across participants.

Additional files

-

Supplementary file 1

Average brain activity that is common for both types of choice (conjunction between PDM and VDM trials).

All p-values are FWE-corrected for the whole brain.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/94576/elife-94576-supp1-v1.docx

-

Supplementary file 2

Average brain activity that is distinct for both types of choice.

All p-values are FWE-corrected for the whole brain. SVC = small-volume correction.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/94576/elife-94576-supp2-v1.docx

-

Supplementary file 3

Regions encoding trialwise accumulated evidence (parametric modulation) during perceptual- and value-based decisions, including SFS SVC results for both tasks.

Note: Trialwise AE during both types of choices correlated negatively with BOLD activity in intraparietal sulcus (IPS) (peak at 𝑥 = −33, 𝑦 = −49, 𝑧 = 58; 𝑆𝑉𝐶 < 0.05; Figure 4—figure supplement 1C) and bilateral fusiform gyrus (right peak at 𝑥 = 33, 𝑦 = −49, 𝑧 = −14; left peak at 𝑥 = −30, 𝑦 = −52, 𝑧 = −11; FWE-corrected with cluster-forming thresholds at 𝑇(19) >2.9; Figure 4—figure supplement 1C).

Note that the inverse of total evidence is directly proportional to the efficiency of evidence accumulation (see Methods for more details; SVC = small-volume correction).

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/94576/elife-94576-supp3-v1.docx

-

Supplementary file 4

Average brain activity that represents efficiency of evidence accumulation for both types of choice (SVC = small-volume correction).

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/94576/elife-94576-supp4-v1.docx

-

Supplementary file 5

Differences-in-differences results for choice accuracy/consistency and response times.

Significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/94576/elife-94576-supp5-v1.docx

-

Supplementary file 6

Differences-in-differences results for choice accuracy/consistency and response times.

Significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (pre–post cTBS: Stimulation effect comparing the last two runs during pre-cTBS and the first two runs during post-cTBS; pre–post cTBS + training: Stimulation effect comparing all runs during pre-cTBS with the first two runs during post-cTBS; pre–post cTBS + control variables: The same as in (a) but we added control variables to test for robustness of the stimulation effect; pre–post cTBS + training + control variables: The same as in (b) but we added control variables to test for robustness of the stimulation effect).

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/94576/elife-94576-supp6-v1.docx

-

Supplementary file 7

Differences-in-differences results for choice accuracy/consistency and response times.

Significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (pre–post cTBS: Stimulation effect comparing the last two runs during pre-cTBS and the first two runs during post-cTBS; pre–post cTBS + training: Stimulation effect comparing all runs during pre-cTBS with the first two runs during post-cTBS; pre–post cTBS + control variables: The same as in (a) but we added control variables to test for robustness of the stimulation effect; pre–post cTBS + training + control variables: The same as in (b) but we added control variables to test for robustness of the stimulation effect).

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/94576/elife-94576-supp7-v1.docx

-

Supplementary file 8

Hierarchical drift-diffusion model (HDDM) group-level parameter estimates for perceptual decisions (PDM) across TMS conditions and evidence levels (δ drift, α boundary, τ non-decision time; DIC reported).

Drift values by evidence level summarise the implied for each bin; separate drift parameters were not estimated for each evidence level.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/94576/elife-94576-supp8-v1.docx

-

Supplementary file 9

Hierarchical drift-diffusion model (HDDM) group-level parameter estimates for value-based decisions (VDM) across TMS conditions and evidence levels (δ, α, τ; DIC reported).

As in Supplementary file 8, evidence-level δ values are descriptive summaries of at each evidence level, not independently fitted drift parameters.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/94576/elife-94576-supp9-v1.docx

-

Supplementary file 10

Hierarchical drift-diffusion model (HDDM) participant-level parameter estimates for PDM (δ, α, τ) with model fit (DIC) per subject.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/94576/elife-94576-supp10-v1.docx

-

Supplementary file 11

Hierarchical drift-diffusion model (HDDM) participant-level parameter estimates for VDM (δ, α, τ) with model fit (DIC) per subject.

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/94576/elife-94576-supp11-v1.docx

-

MDAR checklist

- https://cdn.elifesciences.org/articles/94576/elife-94576-mdarchecklist1-v1.docx