Emergence of alternative stable states in microbial communities undergoing horizontal gene transfer

Figures

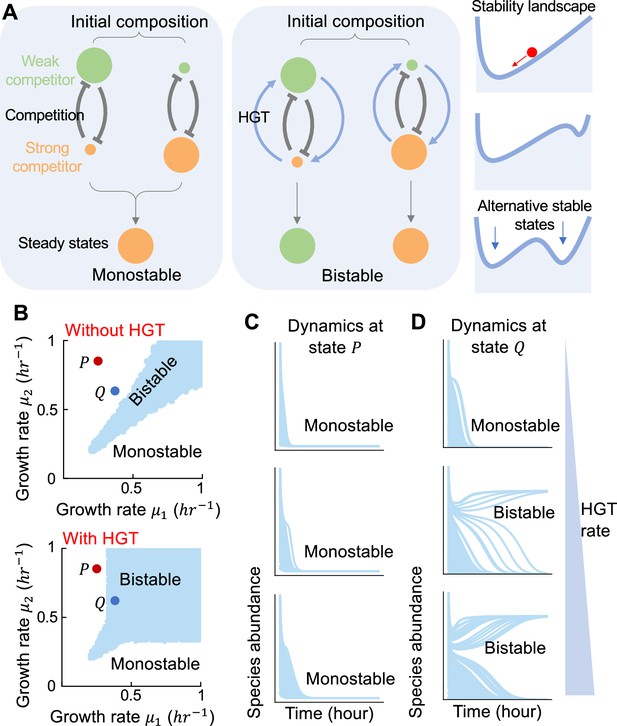

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) promotes bistability of communities consisting of two competing microbes.

(A) Schematics of monostable and bistable systems. A monostable system will always rest at the same steady state no matter where the system starts from. In contrast, a bistable system can reach two distinct steady states, depending on the initial ratio between the two competitors. The right panel is a diagram depicting how a microbial community responds to changes on initial species abundances. The red marble stands for the system state, which will always roll ‘downhill’ on the landscape towards stable states at the low points. The x axis represents the community composition and the valleys in the landscape are the stable states (or equilibrium points) where the community composition will stop changing. Depending on parameter values, the landscape can have one valley (called ‘monostable’) or two valleys (called ‘bistable’). When the system is bistable, the marble can reach either valley, depending on where it starts. (B) The phase diagrams of the population with (bottom panel, ) or without HGT (top panel). Different combinations of and between 0 and 1 hr−1 were tested. For each combination, the initial abundance of each species was randomized 200 times between 0 and 1 following uniform distributions. The system was monostable if all initializations led to the same steady state. Otherwise, the system was bistable. All combinations of and resulting in bistability were marked in blue in the diagram. Other parameters are , , , . Two states, (, ) and (, ), were labeled as examples. (C and D) Population dynamics of and under 100 different initializations. Here, the dynamic changes of species 1’s abundance were shown. Three different HGT rates (0, 0.1, 0.2 hr−1 from top to bottom) were tested. When gene transfer rate increases, the system at changed from monostable to bistable, while the system at remained monostable.

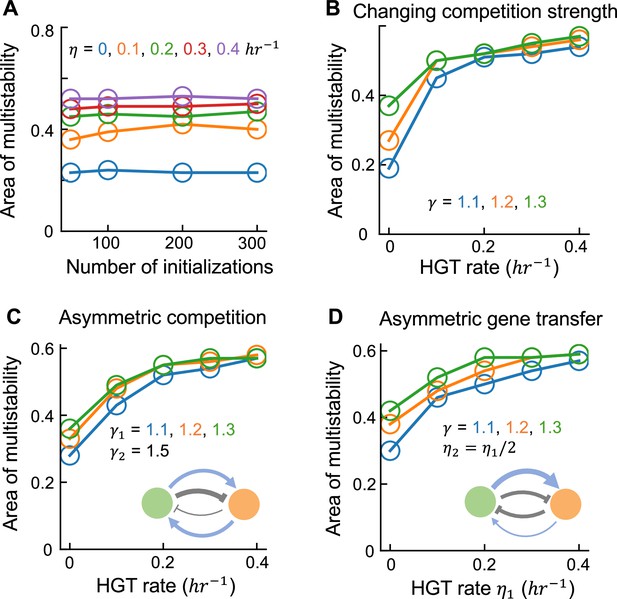

The effect of HGT in two-species populations was robust against a variety of confounding factors.

(A) Changing the number of initializations didn’t influence the main conclusion. Four different numbers of initializations (50, 100, 200, and 300) were tested. (B) Increasing HGT rate promotes bistability under different competition strengths. Here, we assumed symmetric competition, i.e. . Three different values were tested and shown in different colors. Other parameters are , , . and were randomized between 0 and 1 hr−1 following uniform distributions. (C) HGT promotes bistability when interspecies competitions are asymmetric. Asymmetric competition means the inequity between and . We kept as a constant and tested three different values (marked by different colors). Other parameters are , , . (D) HGT promotes bistability when gene transfers are asymmetric. Asymmetric gene transfer means the inequity between and . Here we fixed the ratio between and at 0.5 and tested three different values.

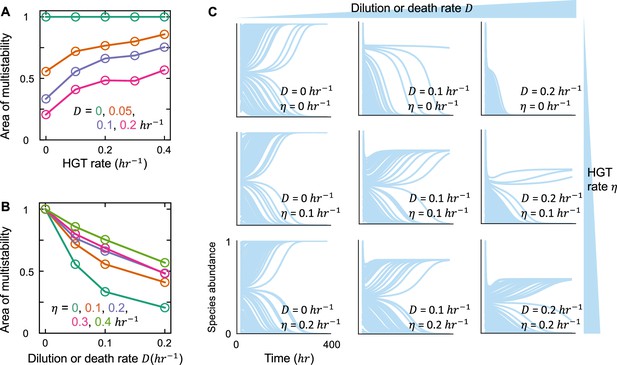

Dilution or death rate shapes the bistability of two-species communities.

(A) The relationship between bistability and HGT rate under different values of . When equals zero, community bistability is not affected by HGT. Whether a given system was bistable was determined by randomly initializing the system 100 times. The total area of bistability region was approximated as the fraction of growth rate combinations that generate bistability out of 500 random combinations. Other parameters are , , . (B) The relationship between bistability and value under different gene transfer rates. (C) Examples of population dynamics under 100 different initializations. Here, the dynamic changes of species 1’s abundance were shown. Three different HGT rates (0, 0.1, 0.2 hr−1 from top to bottom) and three different dilution or death rates (0, 0.1, 0.2 hr−1 from left to right) were tested.

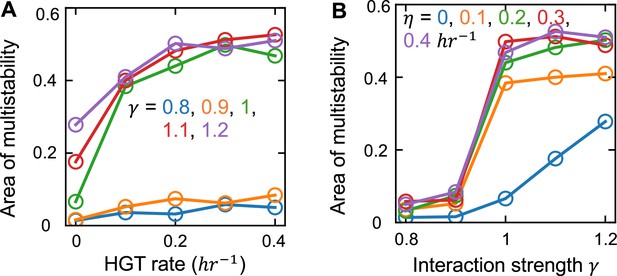

The strength of interspecies competitions influences the bistability of two competing species.

(A) The relationship between bistability and HGT rate under different competition strength . Here, we assumed the interactions between the two species were symmetric, i.e. . When was smaller than 1, the effect of HGT on bistability was weak. Whether a given system was bistable was determined by randomly initializing the system 100 times. The total area of bistability region was approximated as the fraction of growth rate combinations that generate bistability out of 500 random combinations. Other parameters are , , . (B) The relationship between bistability and competition strength under different gene transfer rates.

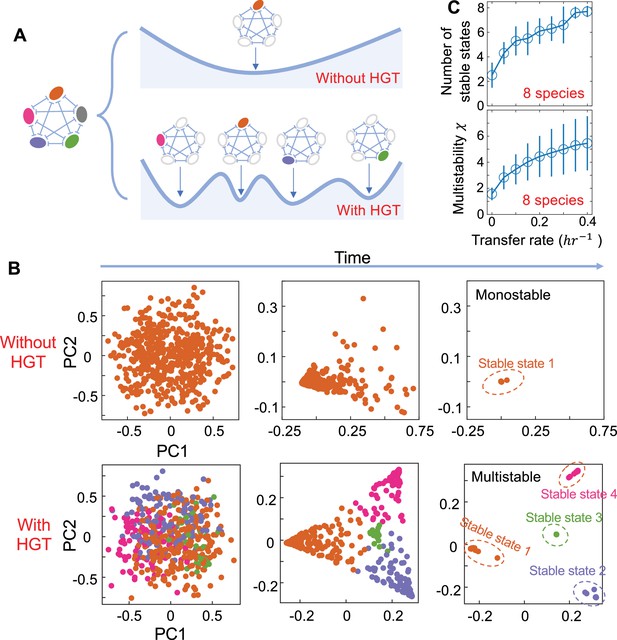

The number of alternative stable states in multi-species communities increases with HGT rate.

(A) A schematic of the stability landscape of a population composed of multiple competing species with or without HGT. Each alternative stable state is characterized by a different dominant species (shown in filled circles). (B) The emergence of alternative stable states in a five-species community with gene transfer. We simulated the dynamics of 500 parallel communities, each with the same kinetic parameters but different initial compositions. The species compositions of these communities at three different timepoints were shown by principal component analysis from left to right. Without HGT (), all populations converged into a single stable state. In contrast, with HGT (), four different attractors appear. Here, populations reaching different stable states were marked with different colors. Other parameters are , , , , , , , , . (C) The number of stable states (top panel) and the multistability coefficient increase with HGT rate in communities consisting of eight competing species. We calculated the number of stable states by randomly initializing the species abundances 500 times between 0 and 1 following uniform distributions. Then we simulated the steady states and clustered them into different attractors by applying a threshold of 0.05 on their Euclidean distances. The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation of 10 replicates. Each replicate corresponded to a different combination of randomized species growth rates.

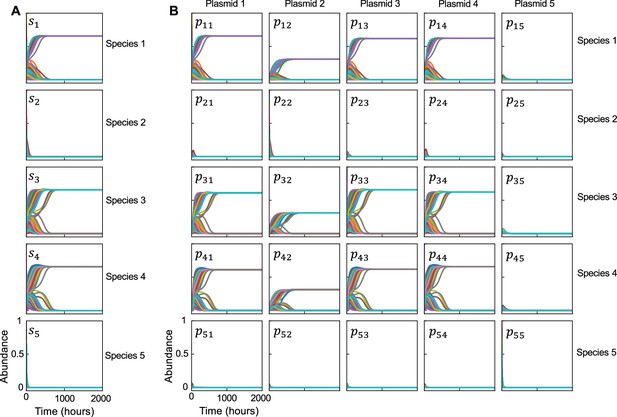

Simulated dynamics of a 5-species community from time 0–2000 hr.

(A) The dynamic change of species abundances. 100 initial conditions were tested and marked with different colors. (B) The dynamic change of MGEs’ abundances. The systems reached steady states within 1000 hr. The parameters are , , , , .

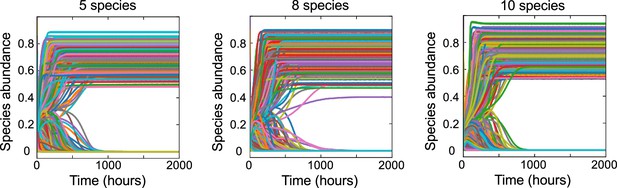

No limit cycles were observed in simulated dynamics.

Populations of 5, 8, and 10 species were examined. For each species number, 200 repeated simulations were carried out, each with randomized kinetic parameters and initial conditions. The abundances of all species in each simulation were shown.

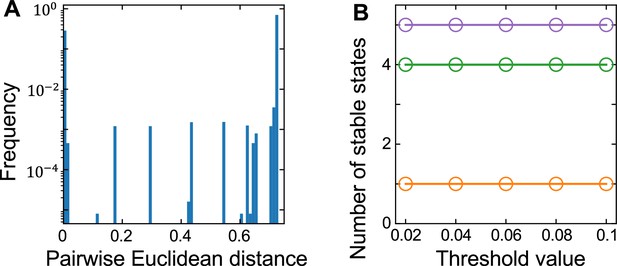

The steady states were grouped into different attractors based on their Euclidean distances.

(A) The distribution of Euclidean distances between any pairs of steady states. Here, a population of five species was shown as an example. The initial abundances of the species were randomized 500 times. Then the steady state corresponding to each initial condition was calculated by numerical simulation. The first peak represents the distances between steady states in the same attraction domain. The other peaks represent the distances across different domains. Other parameters in the simulations are , , , , . (B) The estimated number of stable states was not significantly affected by the distance cut-off value. Three simulation results with randomized growth rates were shown in different colors. Here, the growth rates were randomized in the ranges of following uniform distributions.

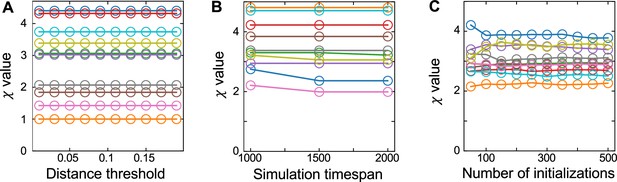

The calculated multistability coefficient under different simulation conditions.

The value was robust to the variations of distance threshold (A), simulation timespan (B), and the number of initializations (C). Here, populations of five species were examined and shown as examples. Other parameters in the simulations are , , , , . Each simulation was repeated 10 times with randomized values. The results of different replicates were shown in different colors.

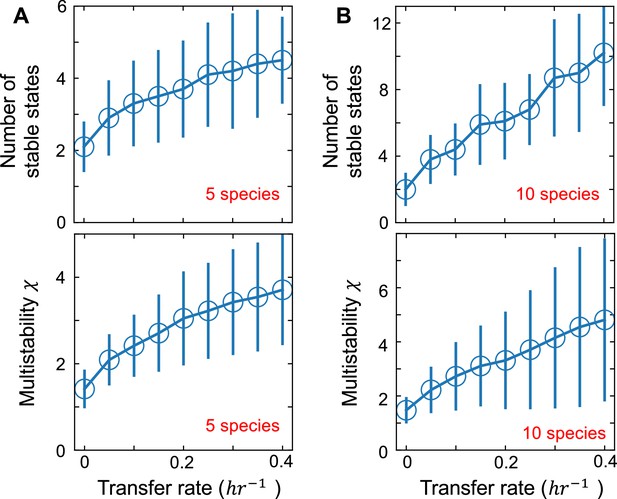

Multistability of complex communities composed of different number of species.

The number of stable states and multistability coefficient increase with HGT rate in communities consisting of 5 (A) or 10 (B) competing species. We calculated the number of stable states by randomly initializing the species abundances 500 times between 0 and 1 following uniform distributions. Then we simulated the steady states and clustered them into different attractors by applying a threshold of 0.05 on their Euclidean distances. The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation of 10 replicates. Each replicate corresponds to a different combination of randomized species growth rates. Other parameters are , , , .

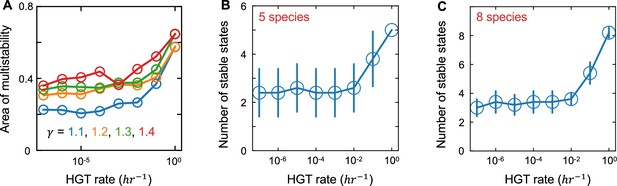

The relationship between community multistability and horizontal gene transfer in a broad range of HGT rate.

(A) Increasing HGT rate promotes the area of multistability of two competing species under different competition strengths . Here, we assumed . Whether a given system was bistable was determined by randomly initializing the system 100 times. The total area of multistability was approximated as the fraction of growth rate combinations that generate bistability out of 500 random combinations. HGT rates from 10–7 to 1 hr−1 were tested. Other parameters are , , . (B) For communities composed of five competing species, promoting HGT rate increased the number of stables states when HGT rate exceeded 10–2 hr−1. The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation of five replicates. Each replicate corresponds to a different combination of randomized species growth rates. Other parameters are , , , . (C) The relationship between the number of stable states and HGT rate for communities composed of eight competing species. The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation of five replicates.

For communities of five species, the number of stable states increases with HGT rate under different values of .

The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation of five replicates. Each replicate corresponds to a different combination of randomized species growth rates. Other parameters are , , , .

Initializing the subpopulations with non-zero abundances didn’t change the main conclusion.

(A) Increasing HGT rate promoted the bistability of two competing species. and were initialized as and , where and were randomized between 0 and 1 following uniform distributions. Four different values were tested and shown in different colors. The total area of multistability was approximated as the fraction of growth rate combinations that generate bistability out of 100 random combinations. Other parameters are , , . and were randomized between 0 and 1 hr−1 following uniform distributions. (B) The number of stable states in 5-species communities increased with HGT rate. were initialized as , where was randomized between 0 and 1 following uniform distributions. The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation of five replicates. Each replicate corresponds to a different combination of randomized species growth rates. (C) The number of stable states in 8-species communities increased with HGT rate. were initialized as , where was randomized between 0 and 1 following uniform distributions. The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation of five replicates.

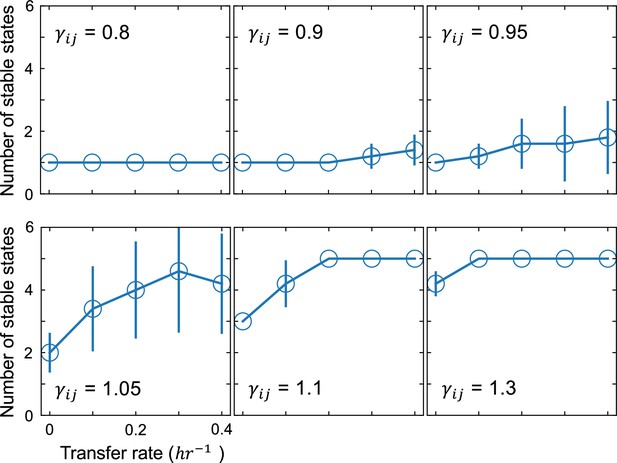

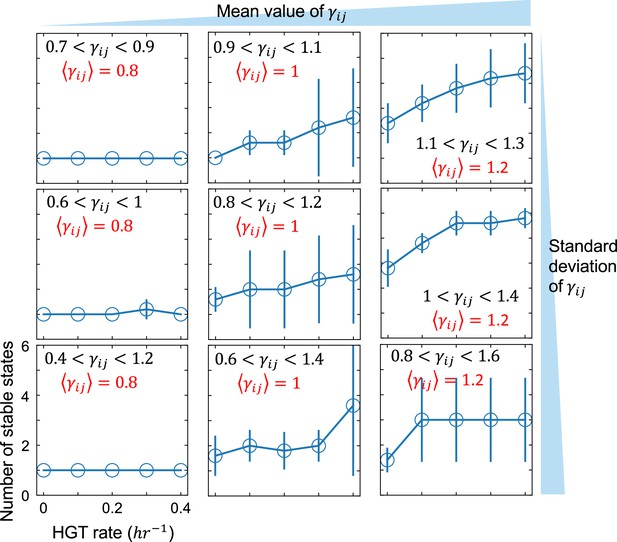

The number of stable states of five-species communities with heterogeneous inter-species interactions.

Here, each was sampled from a uniform distribution with given mean value and standard deviation. Three mean values (from left to right) and three distribution widths (from top to bottom) were tested and shown as examples. The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation of five replicates. Each replicate corresponds to a different combination of randomized species growth rates.

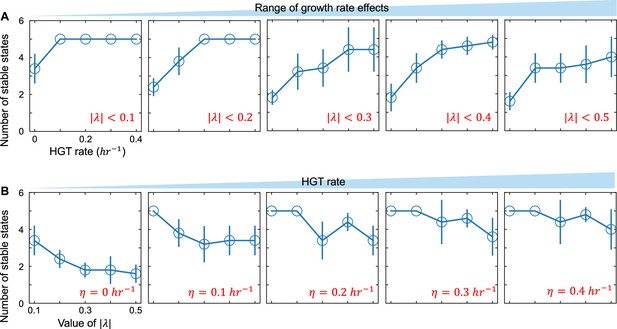

The interplay between HGT and community multistability is not fundamentally changed by the range of growth rate effect .

(A) The relationship between the number of the stable states and HGT rate under different ranges of growth rate effect . Here, the number of stable states of five-species communities was calculated and shown as examples. values were sampled from uniform distributions with given width. Greater distribution width led to larger range of growth rate effects. Five different distribution widths were tested. The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation of five replicates. Other parameters were , , , . (B) The relationship between the number of the stable states and range under different HGT rates.

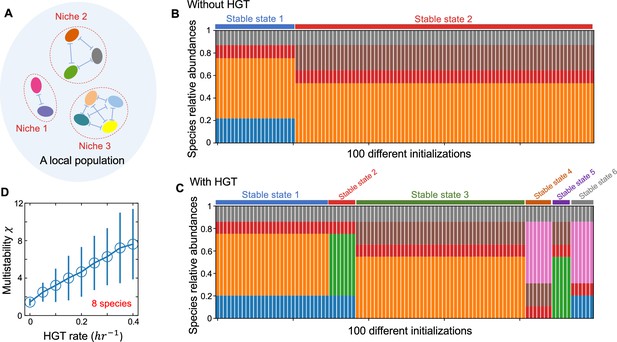

HGT promotes the multistability of communities with multiple niches.

(A) A schematic of a microbial population consisting of multiple niches. Species within each niche share the same carrying capacity and compete with each other, while species from different niches can coexist. (B and C) Multiple alternative stable states emerge in niche communities with gene exchange. Here, a system consisting of 10 species and 4 niches were shown as examples. The steady-state compositions of 100 parallel populations, each with different initializations, were calculated with () or without HGT. The heights of the colored bars represent the relative abundances of different species. Without HGT, 2 stable states existed for the 100 populations, while with HGT, 6 different stable states existed. The carrying capacity of each niche was randomized between 0 and 1. Other parameters are , , . Interspecies competition strength equals 1.05 within each niche. (D) The multistability in niche communities increases with HGT rate. Communities of eight species were considered as an example. The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation of 10 replicates. For each replicate, the species growth rates were randomized between 0.3 and 0.7 hr−1 following uniform distributions. The number of niches were randomized as 2, 3, or 4.

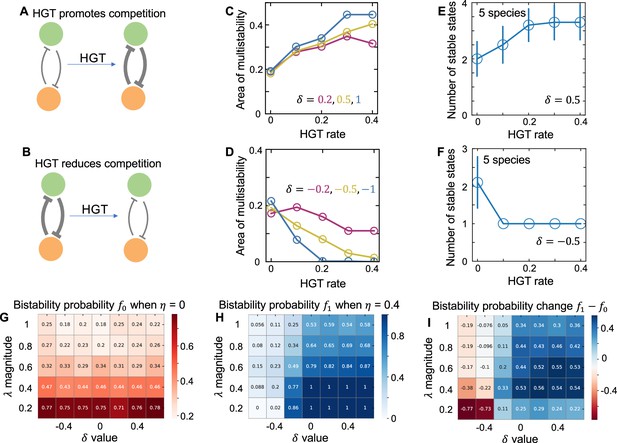

The effects of HGT on population multistability when MGEs promote or reduce the strength of interspecies competition.

(A and B) The schematics of HGT promoting or reducing competition. (C) For populations of two species, when MGEs promote competition, increasing HGT rate enlarges the area of bistability region in the phase diagram. Here, describes the effect of mobile genes on the competition strength. Positive represents HGT promoting competition. In numerical simulations, we tested three different values (marked in different colors). When calculating the area of bistability region, we randomized and 500 times between 0 and 1 hr–1 following uniform distributions while keeping and constants. For each pair of growth rates, we randomized the initial abundance of each species 200 times between 0 and 1 following uniform distributions. The system was monostable if all initializations led to the same steady state. Otherwise, the system was bistable. Then we calculated the fraction of growth rate combinations that generated bistability out of the 500 random combinations. Other parameters are , , . (D) When MGEs reduce competition, the area of bistability region decreases with HGT rate. Three negative values were tested and shown as examples here. (E) For populations of five species, when MGEs promote competition, the number of stable states increases with HGT rate. We calculated the number of stable states by randomly initializing the species abundances 500 times. Then we simulated the steady states and clustered them into different attractors by applying a threshold of 0.05 on their Euclidean distances. The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation of 10 replicates. Each replicate corresponds to a different combination of randomized species growth rates. Other parameters are , , . (F) When MGEs reduce competition, the number of stable states decrease with HGT rate. The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation of 10 replicates. was used in the simulation. (G) For populations of two species without HGT, reducing the magnitude of (promoting ecological neutrality) enlarges the area of bistability. When gene transfer rate equals zero, changing does not influence bistability. When calculating bistability probability, we randomized and 500 times between and following uniform distributions. represents the magnitude of variations. and were calculated as and , respectively. The overall competition strength was calculated as and . We tested different combinations of (the magnitude of variations) and values. We then calculated the fraction () of growth rate combinations that generated bistability out of the 500 random combinations. Other parameters are , , . (H) In populations of two species with HGT, reducing the magnitude of (promoting ecological neutrality) or promoting value enlarges the area of bistability (). being 0.4 was tested as an example here. (I) The effect of HGT on community bistability depends on how mobile genes modify growth rates and competition. Compared with the population without HGT, gene transfer promotes bistability when is zero or positive, while reduces bistability when is largely negative.

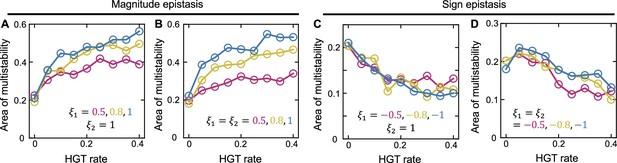

The influence of epistasis on the role of HGT in mediating population bistability.

(A and B) With magnitude epistasis, increasing HGT rate still promotes bistability in populations of two competing species. (C and D) With sign epistasis, increasing HGT rate reduces the area of bistability region. For each type of epistasis, we considered two scenarios. In A and C, host genetic background influences the growth rate effect of only one MGE, while in B and D, host genetic background influences both MGEs. and are defined as and , respectively. and represent magnitude epistasis, while or represents the sign epistasis. Other parameters are , , .

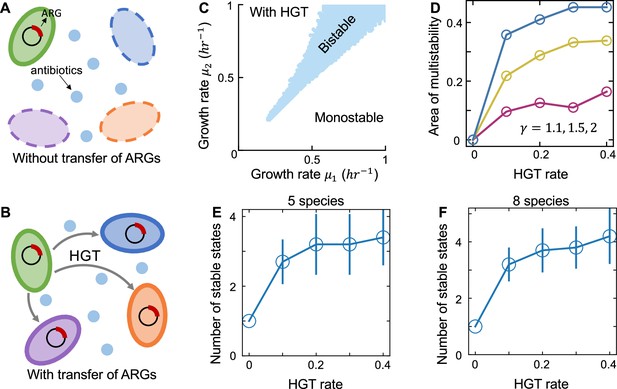

HGT creates chances of multistability for communities under strong environmental selection.

(A and B) The schematics of communities under strong selection. Without HGT, only the donor species carrying the MGE can survive. HGT allows the other species to acquire MGE from the donor, creating opportunities for the other species to survive under strong selections. (C) The phase diagram of two-species populations transferring an MGE. Different combinations of and between 0 and 1 hr−1 were tested. All combinations of and that led to bistability were marked in blue in the diagram. Other parameters are , , , . Here, we assumed that the ARG was initially carried only by species 1. Bistability was more feasible when . (D) Increasing HGT rate enlarges the area of bistability region in the phase diagram of two competing species transferring an MGE. Three different competition strengths were tested (marked in different colors). (E and F) For communities of 5 or 8 species under strong selection, increasing HGT rate promotes the emergence of alternative stable states. We calculated the number of stable states by randomly initializing the species abundances 500 times. Then we simulated the steady states and clustered them into different attractors. The carriage of the mobile gene changed the species growth rate from 0 to a positive value . When calculating the number of stable states in multi-species communities, we randomly drew the values from a uniform distribution between 0.3 and 0.7 hr−1. The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation of 10 replicates. Each replicate corresponds to a different combination of randomized species growth rates. Other parameters are , , .

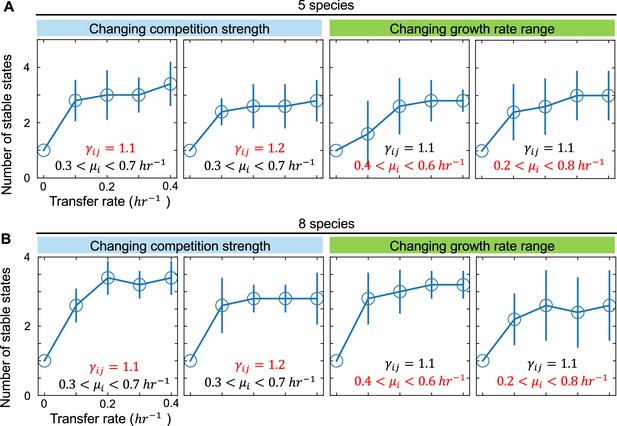

For communities under antibiotic selection, the relationship between the number of stable states and HGT rate under different interactions strengths or growth rate ranges.

Communities composed of 5 (panel A) and 8 species (panel B) were shown as examples. We calculated the number of stable states by randomly initializing the species abundances 500 times. The carriage of the mobile gene modified the species growth rate from 0 to a positive value . When calculating the number of stable states, we randomly drew the values from a uniform distribution in the given range. The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation of 5 replicates. Each replicate corresponds to a different combination of randomized species growth rates. Other parameters are , .

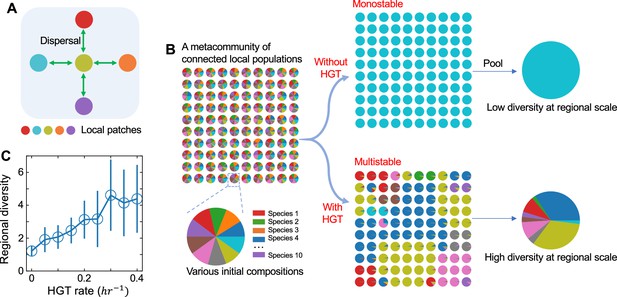

HGT promotes the regional diversity in metacommunities of local populations connected by dispersal.

(A) A schematic of microbial dispersal within the metacommunity. The filled circles represent different local patches. (B) A metacommunity composed of 100 connected patches was shown as an example. Each local population contained 10 competing species and was randomly initialized with different species compositions. Dispersal occurred between neighboring patches with a rate of 0.001 hr−1. Without HGT, the systems were monostable, resulting in low regional diversity. HGT promotes the regional diversity by the emergence of multistability in each local patch. The collective diversity of the metacommunity was calculated by pooling all the local populations together. Other parameters are , , , . (C) The regional diversity of a metacommunity increases with HGT rate. We first pooled all local populations together and calculated the total abundance of every species in the metacommunity. Then we quantified the regional diversity using Shannon index. The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation of 10 replicates.

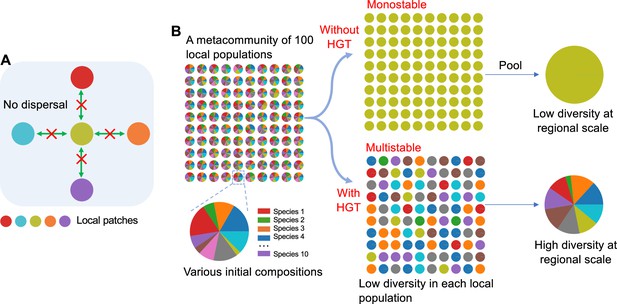

The local multistability enables by HGT gives rise to regional diversity in a metacommunity without dispersal.

(A) A schematic of a metacommunity without dispersal between adjacent local patches. (B) A metacommunity composed of 100 closed local populations was shown as an example. Each local population contained 10 competing species and was randomly initialized with different species compositions. Without HGT, the systems are monostable. All the local populations converge into the same composition, resulting in low regional diversity. In contrast, with HGT (), multiple stable states exist, each characterized by a different dominant species. Different local populations reach distinct stable states, creating species diversity at regional scale even though the local diversity remains low. Here, the collective diversity of the metacommunity was calculated by pooling all the local populations together. Other parameters are , , , .

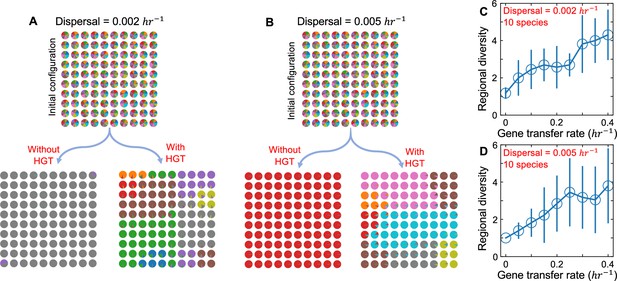

HGT promotes the regional diversity in metacommunities regardless of the dispersal rate.

(A and B) Examples of metacommunities composed of 100 connected patches. Each local population contained 10 competing species and was randomly initialized with different species compositions. Dispersal occurred between neighboring patches with a rate of 0.002 or 0.005 hr−1. Other parameters are , , , . (C and D) The regional diversity of a metacommunity increases with HGT rate. The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation of 10 replicates.

Tables

| Reagent type (species) or resource | Designation | Source or reference | Identifiers | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Software, algorithm | Codes for all numerical simulations | Github repository Hong et al., 2025 | https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14928352 |