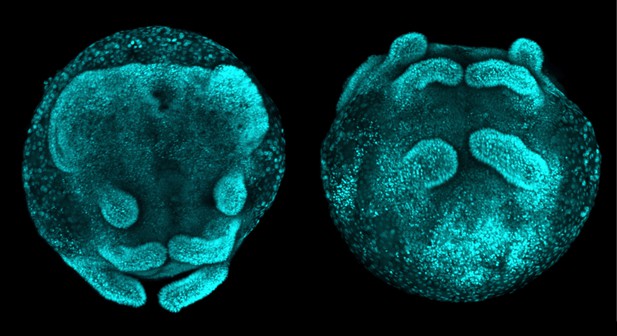

Reducing the activity of a Sox gene interferes with spider segmentation. Image credit: Paese et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Insects, spiders, centipedes and lobsters all belong to a group of animals known as arthropods. A common feature of these animals is that their bodies are made up of repeated segments. However different arthropods build their segmented bodies in different ways. For example, the fruit fly makes all of its segments at the same time, while most other arthropods – including spiders – make a few segments at once and then add the rest, one or two at a time, to the rear end of their bodies.

Recent research in different insects has shown that these two processes – adding segments simultaneously or sequentially – are more similar than previously thought. This research also showed that these processes involve a gene called Dichaete, which belongs to the Sox gene family. However it was not known if Sox genes also control the production of segments in other arthropods like spiders.

Paese et al. have now found that, just like insects, the common house spider does indeed require a Sox gene to form its segments. Specifically, the experiments revealed that spiders need a Sox gene called Sox21b-1 to make both the segments that carry their legs (which are made all at once), and the segments that make up the rear of their bodies (which are added one at a time).

Since spiders and insects both use a Sox gene to control the formation of their body segments, it is likely that the ancestor of arthropods used one too. However, because spiders and insects use a different Sox gene for these processes, Paese et al. suggest that one gene may have replaced the role of the other during the evolution of insects and spiders.

Together these findings broaden the current understanding of how genes interact to organise cells to build organisms and how these processes evolve over time. Furthermore, since Sox genes direct many important events in all animals, including humans, the discovery of a new role for one of these genes may help scientists to better understand the development of other animals too.