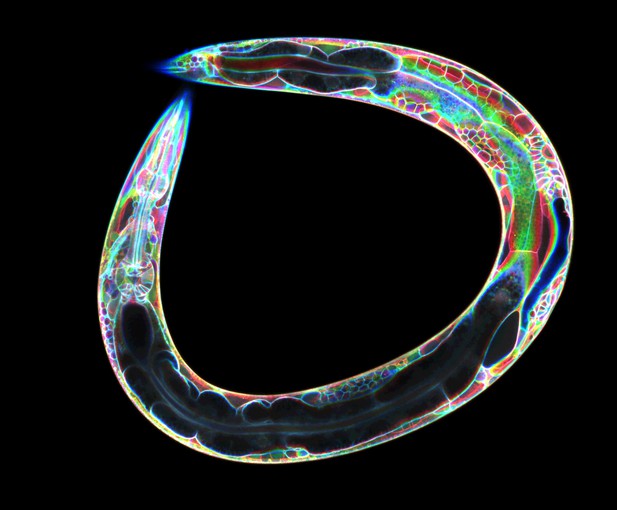

A larva of the nematode worm C. elegans. Image credit: Van den Heuvel et al. (CC BY 4.0)

A cell about to divide must decide where exactly to cut itself in two. Split right down the middle, and the two daughter cells will be identical; offset the cleavage plane to one side, and the resulting siblings will have different sizes, places and fates.

In animals, the splitting of cells is dictated by the location of the spindle, a structure that forms when cable-like microtubules stretch from the cell membrane to attach to the chromosomes. At the membrane, a group of proteins tugs on the microtubules to bring the spindle into the correct position. One of these proteins, dynein, is a motor that uses microtubules as its track to pull the spindle into place. What the other parts of the complex do is still unclear, but a general assumption is that they may be serving as an anchor for dynein.

To test this model, Fielmich, Schmidt et al. removed one or more proteins from the complex in the developing embryos of the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans. A light-activated system then linked the remaining proteins to the membrane by tying them to an artificial anchor. Two of the proteins in the complex could be replaced with the artificial anchor, but pulling forces were absent when dynein was artificially tied to the membrane. This indicates that the motor being anchored at the edge of the cell is not enough for it to pull on microtubules. Instead, the experiments showed that dynein needs to be activated by another component of the complex, a protein called LIN-5. This suggests that individual proteins in the complex have specialized roles that go beyond simply tethering dynein. In fact, steering where LIN-5 was attached on the membrane helped to control the location of the spindle, and therefore of the cleavage plane.

As mammals have a protein similar to LIN-5, dissecting the roles of the components involved in positioning the spindle in C. elegans could help to understand normal and abnormal human development. In addition, these results demonstrate that creating artificial interactions between proteins using light is a powerful technique to study biological processes.