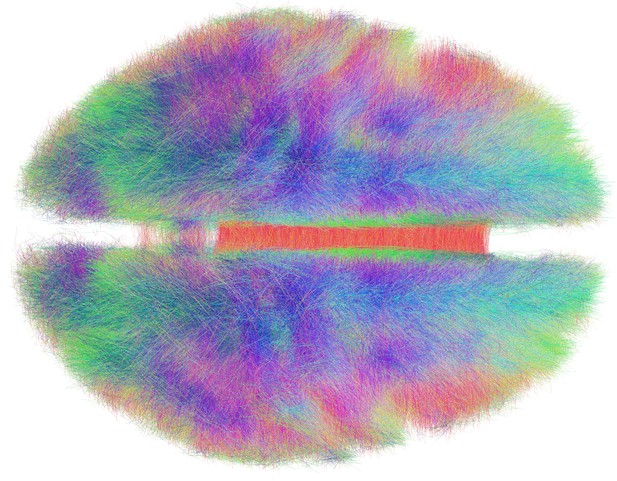

The connectome of the human brain, rendered from visualizations of 20 individuals. Image credit: Andreashorn (CC BY 4.0)

The world around us changes all the time, and the brain must adapt to these changes. This process, known as neuroplasticity, peaks during development. Abnormal sensory input early in life can therefore cause lasting changes to the structure of the brain. One example of this is amblyopia or ‘lazy eye’. Infants who receive insufficient input to one eye – for example, because of cataracts – can lose their sight in that eye, even if the cataracts are later removed. This is because the brain reorganizes itself to ignore messages from the affected eye.

Does the adult visual system also show neuroplasticity? To explore this question, Binda, Kurzawski et al. asked healthy adult volunteers to lie inside a high-resolution brain scanner with a patch covering one eye. At the start of the experiment, roughly half of the brain’s primary visual cortex responded to sensory input from each eye. But when the volunteers removed the patch two hours later, this was no longer the case.

Some areas of the visual cortex that had previously responded to stimuli presented to the non-patched eye now responded to stimuli presented to the patched eye instead. The patched eye had also become more sensitive to visual stimuli. Indeed, these changes in visual sensitivity correlated with changes in brain activity in a pathway called the ventral visual stream. This pathway processes the fine details of images. Groups of neurons within this pathway that responded to stimuli presented to the patched eye were more sensitive to fine details after patching than before.

Visual regions of the adult brain thus retain a high degree of neuroplasticity. They adapt rapidly to changes in the environment, in this case by increasing their activity to compensate for a lack of input. Notably, these changes are in the opposite direction to those that occur as a result of visual deprivation during development. This has important implications because lazy eye syndrome is currently considered untreatable in adulthood.