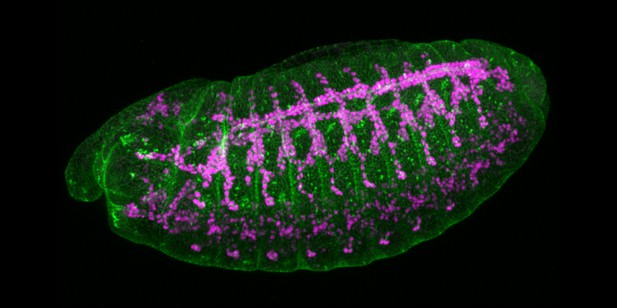

A fruit fly embryo stained to show the expression of trachealess in magenta, and a common membrane protein in green. Image credit: Takefumi Kondo (CC BY 4.0)

Cells in developing organs have two important decisions to make: where to be and what cell type to become. If cells end up in the wrong places, they can stop an organ from working, so it is vital that one decision depends upon the other. The so-called progenitor cells responsible for forming the trachea, for example, can either become part of a flat sheet or part of a tube. The cells on the sheet need to become epidermal cells, while the cells in the tube need to become tracheal cells. Work on fruit flies found that a gene called 'trachealess' plays an important role in this process. Without it, developing flies cannot make a trachea at all.

At the start of trachea development, some of the cells form thickened structures called placodes. The progenitor cells in the placodes start to divide, and the structures buckle inwards to form pockets. These pockets then lengthen into tubes. The trachealess gene codes for a protein that works as a genetic switch. It turns other genes on or off, helping the progenitor cells inside the pockets to become tracheal cells. But, it is not clear whether trachealess drives the formation of the pockets: the progenitor cells first decide what to be; or whether pocket formation tells the cells to use trachealess: the progenitor cells first decide where to be.

To find out, Kondo and Hayashi imaged developing fly embryos and saw that the trachealess gene does not start pocket formation, but that it is essential to maintain the pockets. Flies without the gene managed to form pockets, but they did not last long. Looking at embryos with defects in other genes involved in pocket formation revealed why. In these flies, some of the progenitor cells using trachealess got left behind when the pockets started to form. But rather than forming pockets of their own (as they might if trachealess were driving pocket formation), they turned their trachealess gene off. Progenitor cells in the fly trachea seem to decide where to be before they decide what cell type to become. This helps to make sure that trachea cells do not form in the wrong places.

A question that still remains is how do the cells know when they are inside a pocket? It is possible that the cells are sensing different mechanical forces or different chemical signals. Further research could help scientists to understand how organs form in living animals, and how they might better recreate that process in the laboratory.