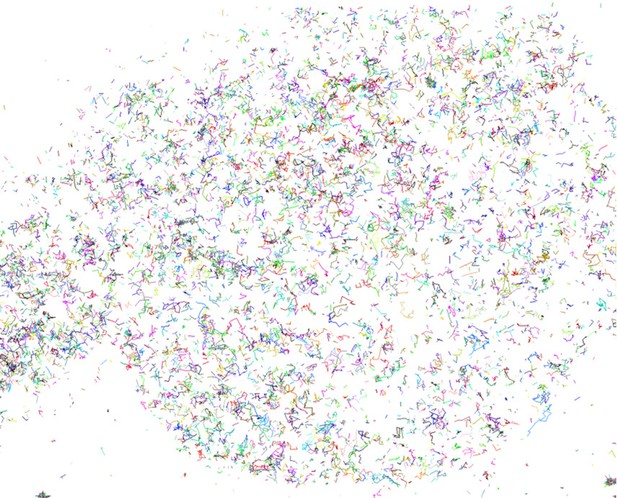

Map showing the trajectories of individual molecules of activated Ras as they move along the membrane. Image credit: Yerim Lee (CC BY 4.0)

The Ras family of proteins play an important role in relaying signals from the outside to the inside of the cell. Ras proteins are attached by a fatty tail to the inner surface of the cell membrane. When activated they transmit a burst of signal that controls critical behaviors like growth, survival and movement. It has been suggested that to prevent these signals from being accidently activated, Ras molecules must group together at specialized sites within the membrane before passing on their message. However, visualizing how Ras molecules cluster together at these domains has thus far been challenging. As a result, little is known about where these sites are located and how Ras molecules come to a stop at these domains.

Now, Lee et al. have combined two microscopy techniques called ‘single-particle tracking’ and ‘photoactivated localization microscopy' to track how individual molecules of activated Ras move in human cells grown in the lab. This revealed that Ras molecules quickly diffuse along the inside of the membrane until they arrive at certain locations that cause them to halt. However, computer models consisting of just the ‘fast’ and ‘immobile’ state could not correctly re-capture the way Ras molecules moved along the membrane. Lee et al. found that for these models to mimic the movement of Ras, a third ‘intermediate’ state of Ras mobility needed to be included.

To investigate this further, Lee et al. created a fluorescent map that overlaid all the individual paths taken by each Ras molecule. The map showed regions in the membrane where the Ras molecules had stopped and possibly clustered together. Each of these ‘immobilization domains’ were then surrounded by an ‘intermediate domain’ where Ras molecules had begun to slow down their movement. Although the intermediate domains did not last long, they seemed to guide Ras molecules into the immobilization domains where they could cluster together with other molecules. From there, the cell constantly removed Ras molecules from these membrane domains and returned them back to their ‘fast’ diffusing state.

Mutations in Ras proteins occur in around a third of all cancers, so a better understanding of their dynamics could help with future drug discovery. The methods used here could also be used to investigate the movement of other signaling molecules.