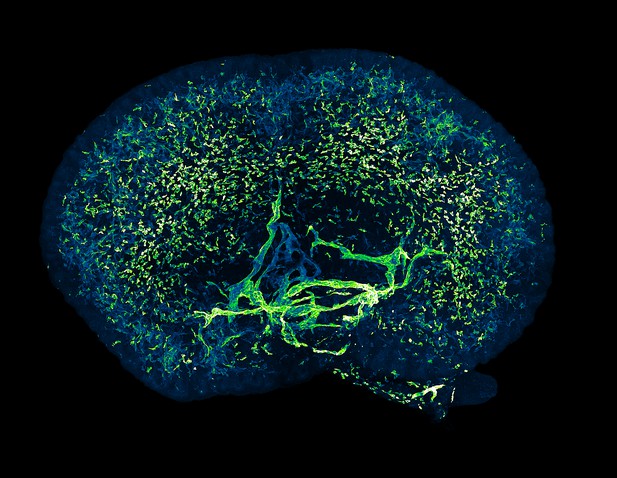

Kidney from a mouse embryo showing the developing lymphatic vessel network. Image credit: Daniyal Jafree (CC BY 4.0)

In most organs in the body, fluid tends to build up in the spaces between cells, especially if the organs become inflamed. Each organ has a ‘waste disposal system’; a set of specialized tubes called lymphatic vessels, to clear away this excess fluid and keep a check on inflammation. Defects in these tubes have been linked to a wide range of diseases including heart attacks, obesity, dementia and cancer.

The kidneys are responsible for filtering blood and balancing many of the body’s chemical processes. Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is the most common genetic kidney disorder and it results in cysts filled with fluid building up in the kidney. The growth of cysts in PKD may be due to a problem with the lymphatic vessels. However, compared to other organs, how lymphatic vessels first form within the kidney and what they do is not well understood.

Now, Jafree et al. have used three-dimensional imaging to study how lymphatic vessels form in the kidneys of mice and humans. The experiments showed that lymphatic vessels first appear when mouse kidneys are about half developed, and start to grow rapidly when the kidneys are thought to begin filtering blood. Clusters of cells that may help lymphatic vessels to grow were also found hidden deep within the kidneys of mouse embryos. Treating the kidneys with a factor that stimulates the growth of lymphatic vessels increased the numbers of these clusters. Jafree et al. found similar clusters of cells in human kidneys, suggesting that lymphatic vessels in the kidneys of different mammals may develop in the same way.

Further experiments showed that the lymphatic vessels of kidneys in mice with PKD become distorted early on in the disease, when cysts are still small and before the mice develop symptoms. In the future, identifying drugs that target kidney lymphatic vessels may lead to more effective treatments for patients with PKD and other kidney diseases.