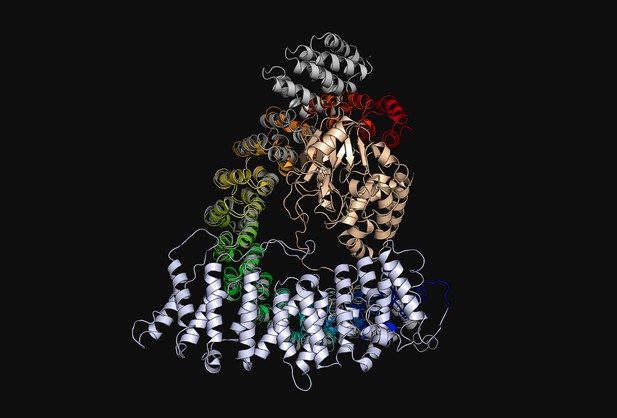

The phosphatase PP2A. Image credit: Opabinia regalis (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Cells maintain a fine balance of signals that promote or counter cell growth and division. Two sets of enzymes – called kinases and phosphatases – contribute to this balance. In general, kinases “switch on” other proteins by tagging them with a phosphate molecule. This process is called phosphorylation. Phosphatases, on the other hand, dephosphorylate these proteins, switching them off. Cancer cells often have mutations that activate kinases to drive cancer growth. The same cells can have mutations that inactivate the phosphatases or reduce their abundance. The roles of phosphatases in cancer are still being studied. One major hurdle in this research is that it is not always clear how they recognize the proteins they dephosphorylate.

Protein phosphatase 2A (or PP2A for short) is one of the phosphatases that is often mutated or deleted in human cancers. Even just reduced levels of PP2A can promote cancer. Kim, Berrios, Kim, Schade et al. used an experimental trick to decrease the phosphatase activity of PP2A in human cells growing in a dish. Biochemical analysis of these cells showed that, as expected, many proteins were now in their phosphorylated states. Unexpectedly, however, some proteins were dephosphorylated under these conditions. One of these proteins was called MAP4K4. In the case of MAP4K4, the dephosphorylated state contributes to the growth of the cancer cell. Kim et al. carried out further genetic and biochemical experiments to show that, in these cells, PP2A and MAP4K4 stay physically connected to one another. This connection was enabled by a group of proteins called the STRIPAK complex. The STRIPAK proteins directed the remaining PP2A towards MAP4K4. Low levels or activity of PP2A could, therefore, promote cancer in a different way.

Taken together, PP2A is not a single phosphatase that always turns proteins off, but rather is a dual switch that turns off some proteins while turning on others. Future experiments will explore to what extent these findings also apply in tumors. Information about how mutations in PP2A affect human cancers could suggest new targets for cancer drugs.