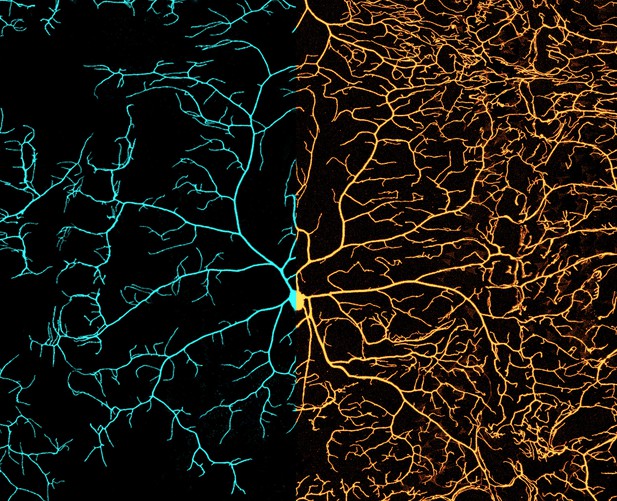

A composite image made of sensory neurons in two different fruit fly larvae. One larva grew in abundant nutrients (left, cyan) while the other grew in scarce nutrients (right, orange). Malnutrition causes neurons to grow more complex dendritic structures. Image credit: Poe, Xu et al. (CC BY 4.0)

The organs of a young animal develop in a carefully controlled way to reach the right size relative to each other. However, if the animal’s diet does not contain the right amount of nutrients — a condition known as malnutrition – the body prioritizes the needs of the brain and other vital organs. This means that certain organs keep on growing while others stop.

The brain is at the center of the nervous system, which is formed of networks of nerve cells (or neurons) that rapidly carry messages around the body. In the larvae of malnourished fruit flies, a molecular signal allows the nervous system to continue making new neurons as other parts of the body slow down their growth.

During development, neurons also connect to each other by growing tree-like structures known as dendrites. However, it remained unclear whether the growth of dendrites was also protected during episodes of malnutrition.

To address this question, Poe, Xu et al. performed experiments in the larvae of fruit flies, focusing on a type of neuron whose dendrites extend into the skin. When nutrients were scarce, the neurons grew more rapidly than the surrounding skin cells, resulting in dendrite overgrowth. Compared to neurons, the skin cells had higher levels of a stress sensor known as FoxO, which stops cell growth when nutrients are scarce. Conversely, low quantities of FoxO in neurons allow these cells to keep on growing dendrites, which ultimately helps the starved animals to better react to their environment.

These results suggest that the growth of neurons and their connecting structures is preserved during malnutrition. Ultimately, dissecting how organisms prioritize resources can help to develop new approaches to treat human conditions that emerge during malnutrition.