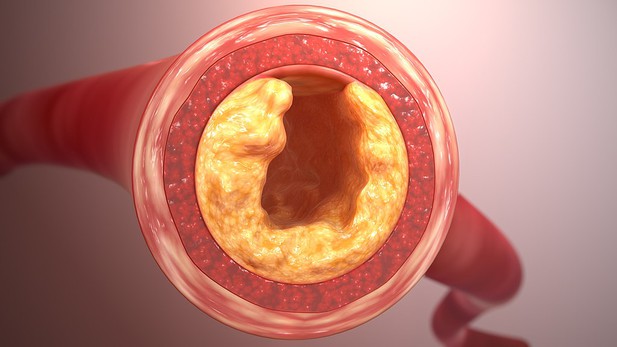

Plaque lining the inner cell layer of an artery. Image credit: Scientific Animations, Girish Khera (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Cholesterol and triglycerides are fatty substances found in the blood. They are crucial components of cell membranes and important for a variety of processes in the body. But, too much, or too little blood fat can damage the blood vessels. For example, high levels of fat in the blood can clog arteries, which can increase the chances of heart disease, heart attacks and strokes.

Fat starts to build up if ‘bad’ fats, such as triglycerides and LDL cholesterol, are too high. But it can also happen if levels of 'good' fats, like HDL cholesterol, are too low. The causes of, and treatments for, these different types of dyslipidaemia (or fat levels outside normal ranges) are not the same. So, to plan interventions effectively, public health authorities need to know which type of blood fat imbalance is most common in the local population, and whether this has changed over time. In many parts of the world, this kind of information is available, but in Latin America and the Caribbean the data is incomplete.

To address this, Carrillo-Larco et al. reviewed around 200 previous studies from across Latin America and the Caribbean. This revealed that, since 2005, low HDL cholesterol has been the most common type of dyslipidaemia in this region, followed by elevated triglycerides, and third, high LDL cholesterol. These patterns have changed little over the years.

In many parts of the world, public health guidelines for dyslipidaemia focus on treatment specifically for high LDL cholesterol. But this new data suggests that guidelines should also include recommendations for HDL cholesterol, in particular in Latin America and the Caribbean. And, with a clearer understanding of the current pattern of blood fat imbalances in this region, researchers now have a baseline against which to measure the success of any new health policies. In the future, a multi-country study to measure blood fats in the general population could provide even more detail. But, until then, this work provides a starting point for customised health interventions.