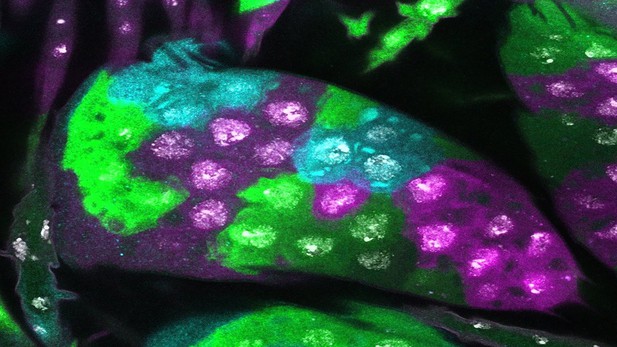

A group of rectal cells in Drosophila melanogaster with fluorescent proteins in three different colors, indicating that cytoplasm is being shared. Image credit: Benjamin Stormo (CC BY 4.0)

Most cells are self-contained – they have a cell membrane that delimits and therefore defines the cell, separating it from other cells and from its environment. But sometimes several cells interconnect and form collectives so they can pool their internal resources. Some of the best-known examples of this happen in animal muscle cells and in the placenta of mammals. These cell collectives share their cytoplasm – the fluid within the cell membrane that contains the cell organelles – in one of two ways. Cells can either remain linked instead of breaking away when they divide, or they can fuse their membranes with those of their neighbors. Working out how cells link to their neighbors is difficult when so few examples of cytoplasm sharing are available for study. One way to tackle this is to try and find undiscovered cell collectives in an animal that is already heavily studied in the lab, such as the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster.

Peterson et al. used a genetic system that randomly labels each cell of the developing fly with one of three fluorescent proteins. These proteins are big and should not move between cells unless they are sharing their cytoplasm. This means that any cell containing two or more different colors of fluorescent protein must be connected to at least one of its neighbors. The experiment revealed that the cells of the fruit fly rectum share their cytoplasm in a way never seen before. This sharing occurs at a consistent point in the development of the fruit fly and uses a different set of genes to those used by interconnecting cells in mammal muscles and placenta. These genes produce proteins that reshape the membranes of the cells and fit them with gap junctions – tiny pores that cross from one membrane to the next, allowing the passage of very small molecules. In this case, the gap junctions allowed the cells to share molecules much larger than seen before. The result is a giant cell membrane containing the cytoplasm and organelles of more than a hundred individual cells.

These findings expand scientists’ understanding of how cells in a tissue can share cytoplasm and resources. They also introduce a new tissue in the fruit fly that can be used in future studies of cytoplasm sharing. Relatives of fruit flies, including fruit pests and mosquitos, have similar cell structure to the fruit fly, which means that further investigations using this system could result in advances in agriculture or human health.