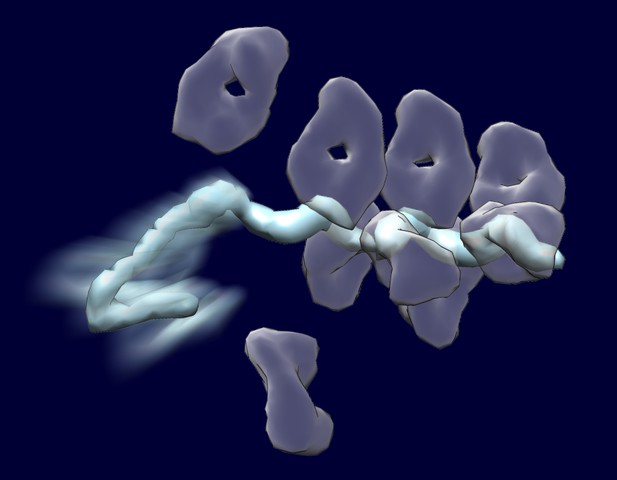

Structural representation of a protein (light blue rod) found on the surface of malaria-causing parasites transitioning into a stable, spiral-like structure when bound by multiple antibodies (dark blue circles). Image credit: Iga Kucharska, Elaine Thai and Jean-Philippe Julien (CC BY 4.0)

Malaria is a significant health concern, killing about 400,000 people each year. While antimalarial drugs and insecticides have successfully reduced deaths over the last 20 years, the parasite that causes malaria is starting to gain resistance to these treatments. Vaccines offer an alternative route to preventing the disease. However, the most advanced vaccine currently available provides less than 50% protection.

Vaccines work by encouraging the body to develop proteins called antibodies, which can recognize the parasite and trigger an immune response that blocks the infection. These antibodies target a molecule on the parasite’s surface called circumsporozoite protein, or CSP for short. Therefore, having a better understanding of how antibodies interact with CSP could help researchers design more effective treatments.

A lot of what is known about malaria has come from studying this disease in mice. However, it remained unclear whether antibodies produced in rodents combat the malaria-causing parasite in a similar manner to human antibodies. To answer this question, Kucharska, Thai et al. studied a mouse antibody called 3D11, which targets CSP on the surface of a parasite that causes malaria in rodents. The interaction between CSP and 3D11 was studied using three different techniques in order to better understand how the structure of CSP changes when bound by antibodies.

The experiments showed that although CSP has a highly flexible structure, it forms a more stable, spiral-like architecture when bound to multiple copies of 3D11. A similar type of assembly was previously observed in studies investigating how CSP interacts with human antibodies. Further investigation revealed that the molecular connections between 3D11 and CSP share a lot of similarities with how human antibodies recognize CSP.

These findings reveal how mammals evolved similar mechanisms for detecting and inhibiting malaria-causing parasites. This highlights the robust features antibodies need to launch an immune response against malaria, which could help develop a more effective vaccine.