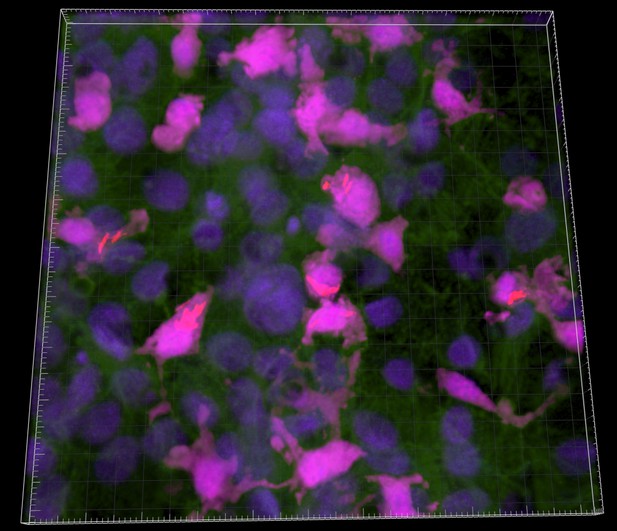

Image of part of the tissue on the chip, with M. tuberculosis shown in red, immune cells shown in bright pink, cellular nuclei (containing the DNA) shown in dark blue, and a protein that is present in both lung cells and immune cells shown in green. Image credit: Thacker et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Tuberculosis is a contagious respiratory disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Droplets in the air carry these bacteria deep into the lungs, where they cling onto and infect lung cells. Only small droplets, holding one or two bacteria, can reach the right cells, which means that just a couple of bacterial cells can trigger an infection. But people respond differently to the bacteria: some develop active and fatal forms of tuberculosis, while many show no signs of infection. With no effective tuberculosis vaccine for adults, understanding why individuals respond differently to Mycobacterium tuberculosis may help develop treatments.

Different responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis may stem from the earliest stages of infection, but these stages are difficult to study. For one thing, tracking the movements of the few bacterial cells that initiate infection is tricky. For another, studying the molecules, called ‘surfactants’, that the lungs produce to protect themselves from tuberculosis can prove difficult because these molecules are necessary for the lungs to inflate and deflate normally. Normally, the role of a molecule can be studied by genetically modifying an animal so it does not produce the molecule in question, which provides information as to its potential roles. Unfortunately, due to the role of surfactants in normal breathing, animals lacking them die. Therefore, to reveal the role of some of surfactants in tuberculosis, Thacker et al. used ‘lung-on-chip’ technology. The ‘chip’ (a transparent device made of a polymer compatible with biological tissues) is coated with layers of cells and has channels to simulate air and blood flow.

To see what effects surfactants have on M. tuberculosis bacteria, Thacker et al. altered the levels of surfactants produced by the cells on the lung-on-chip device. Two types of mouse cells were grown on the chip: lung cells and immune cells. When cells lacked surfactants, bacteria grew rapidly on both lung and immune cells, but when surfactants were present bacteria grew much slower on both cell types, or did not grow at all. Further probing showed that the surfactants pulled out proteins and fats on the surface of M. tuberculosis that help the bacteria to infect their host, highlighting the protective role of surfactants in tuberculosis.

These findings lay the foundations for a system to study respiratory infections without using animals. This will allow scientists to study the early stages of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, which is crucial for finding ways to manage tuberculosis.