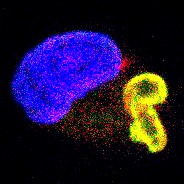

An immune cell (with its DNA shown in blue) that has engulfed a tagged protein (shown in yellow). To demonstrate that the protein was indeed correctly tagged, the protein itself was visualized in red, while the tag was visualized in green; when visualized together the two colors combine to give a yellow signal. Image credit: Tamburini lab (CC BY 4.0)

The lymphatic system is a network of ducts that transports fluid, proteins, and immune cells from different organs around the body. Lymph nodes provide pit stops at hundreds of points along this network where immune cells reside, and lymph fluid can be filtered and cleaned. When pathogens, such as viruses or bacteria, enter the body during an infection, fragments of their proteins can get swept into the lymph nodes. These pathogenic proteins or protein fragments activate resident immune cells and kickstart the immune response. Vaccines are designed to mimic this process by introducing isolated pathogenic proteins in a controlled way to stimulate similar immune reactions in lymph nodes.

Once an infection has been cleared by the immune system, or a vaccination has triggered the immune system, most pathogenic proteins get cleared away. However, a small number of pathogenic proteins remain in the lymph nodes to enable immune cells to respond more strongly and quickly the next time they see the same pathogen. Yet it is largely unclear how much protein remains for training and how or where it is all stored. Current techniques are not sensitive or long-lived enough to accurately detect and track these small protein deposits over time.

Walsh, Sheridan, Lucas, et al. have addressed this problem by developing biological tags that can be attached to the pathogenic proteins so they can be traced. These tags were designed so the body cannot easily break them down, helping them last as long as the proteins they are attached to. Walsh, Sheridan, Lucas et al. tested whether vaccinating mice with the tagged proteins allowed the proteins to be tracked. The method they used was designed to identify individual cell types based on their genetic information along with the tag. This allowed them to accurately map the complex network of cells involved in storing and retrieving archived protein fragments, as well as those involved in training new immune cells to recognize them.

These results provide important insights into the protein archiving system that is involved in enhancing immune memory. This may help guide the development of new vaccination strategies that can manipulate how proteins are archived to establish more durable immune protection. The biological tags developed could also be used to track therapeutic proteins, allowing scientists to determine how long cancer drugs, antibody therapies or COVID19 anti-viral agents remain in the body. This information could then be used by doctors to plan specific and personalized treatment timetables for patients.