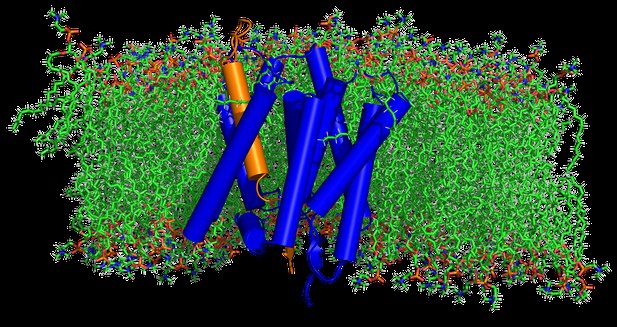

The structure of PSH (blue) is shown binding its substrate (orange) embedded in a lipid bilayer (green). Image credit: Lukas P Feilen (CC BY 4.0)

Cutting proteins into pieces is a crucial process in the cell, allowing several important processes to take place, including cell differentiation (which allows cells to develop into specific types), cell death, protein quality control, or even where in the cell a protein will end up. However, the specialized proteins that carry out this task, known as proteases, can also be involved in the development of disease. For example, in the brain, a protease called γ-secretase cuts up the amyloid-β protein precursor, producing toxic forms of amyloid-β peptides that are widely believed to cause Alzheimer’s disease.

Proteases like γ-secretase carry out their role in the membrane, the layer of fats (also known as lipids) that forms the outer boundary of the cell. The environment in this area of the cell can influence the activity of proteases, but it is poorly understood how this happens.

One way to address this question would be to compare the activity of γ-secretase in the lipid environment of the membrane to its activity when it is entirely surrounded by different molecules, such as detergent molecules. Unfortunately, γ-secretase is not active when it is removed from its lipid environment by a detergent, making it difficult to perform this comparison. To overcome this issue, Feilen et al. chose to study PSH, a protease similar to γ-secretase that produces the same amyloid-β peptides but remains active in detergent.

When Feilen et al. mixed PSH with lipid molecules like those found in the membrane and amyloid-β precursor protein, PSH produced amyloid-β peptides including those that are thought to cause Alzheimer’s. However, when a detergent was substituted for the lipid molecules this led to longer amyloid-β peptides than usual, indicating that PSH was not able to cut proteins as effectively. The change in environment appeared to reduce PSH’s ability to progressively trim small segments from the peptides.

Computer modelling of the protease’s structure in lipids versus detergent supported the experimental findings: the model predicted that the areas of PSH important for recognizing and cutting other proteins would be more stable in the membrane compared to the detergent.

These results indicate that the cell membrane plays a vital role in the stability of the active regions of proteases that are cleaving in this environment. In the future, this could help to better understand how changes to the lipid molecules in the membrane may contribute to the activity of γ-secretase and its role in Alzheimer’s disease.