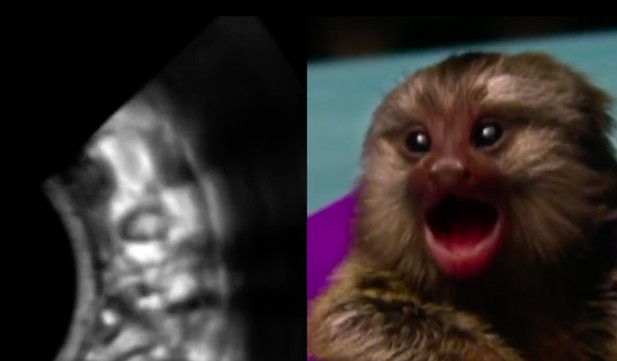

A marmoset in the womb (left) practising the cries it will make as a newborn (right). Image credit: Adapted from Narayanan et al. (CC BY 4.0)

Much like human babies, newborn monkeys cry and coo to get their caregiver’s attention. They all produce these sounds in the same way. They push air from the lungs to vibrate the vocal cords, and adjust the movement of their jaws, lips, tongue and other muscles to create different kinds of sounds.

Ultrasounds show that human fetuses begin making crying-like mouth movements during the last trimester of pregnancy. Yet the prenatal development of this crucial skill remains unclear, as most studies of early primate vocalization take place after birth.

To explore this question, Narayanan et al. focused on a small species of monkeys known as marmosets. Regular ultrasounds were performed on four pregnant marmosets, starting on the first day the fetuses’ faces became visible and ending the day before delivery. The developing marmosets acquired the ability to independently move their mouth from their head over time, a skill crucial for feeding and vocalizing. By the end of pregnancy, a subset of fetal mouth movements were nearly identical to those produced when baby marmosets call for their caregivers after birth.

Human ultrasound studies are needed to confirm whether vocal development follows a similar trajectory in our species.This is likely given the developmental similarities between both species. If so, work in marmosets could be helpful to understand how conditions such as cerebral palsy interfere with this process, and to potentially develop early interventions.