Scientists have revealed a key factor that influences whether malignant cells will grow to form a tumour, in a new study published today in eLife.

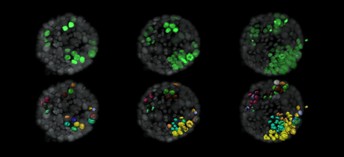

Evolution of tumour cells (green) within a normal organoid (grey). The lower panel shows surface rendition of tumour cells and labels new cells that arise from a single cell in the same colour. Image credit: Ashna Alladin (CC BY 4.0)

The research combined the use of mouse breast mini-organs with continuous imaging at single-cell resolution to reveal how a tumour becomes established. The results provide insights into the behaviour of individual breast cancer cells that could lead to new strategies on how to handle the disease.

Most studies of cancer biology use tissue samples or cells where every cell has faulty mutations that have the potential to form a tumour. This means it is impossible to recreate the very first stages of disease when a single mutated cell overcomes its normal surroundings and develops into cancer.

“To study tumour initiation, models need to be established where only a few malignant cells expand in the context of their immediate non-tumour environment,” explains lead author Ashna Alladin, a postdoctoral researcher in senior author Martin Jechlinger’s lab at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL), Heidelberg, Germany. “We created a model of breast cancer development where only single cells activate cancer-promoting oncogenes within otherwise healthy breast tissue, and then followed the fate of these cancerous cells.”

To develop their model, the team grew organoids (mini-organs) from mouse breast tissue which recreate the breast structure. They focused on tiny glands within the breast called ‘acini’. They then introduced a cancer-promoting gene into a few individual cells within these acini. Some of the cells then had a second gene added, which allowed the cancer-promoting gene to be switched on in the presence of a drug called doxorubicin. This means the team could control which cells had the cancer-promoting gene switched on and were ‘transformed’ into malignant cells, and record when the cells were transformed.

The cells were also labelled so that they could be individually tracked every 10 minutes for up to four days using a method called light-sheet microscopy. In this way, the team could see exactly which cells went on to initiate a tumour, and which cells did not.

To determine what influences the individual malignant cells to develop a tumour, the researchers designed a computer algorithm that took all the information from the cell images and looked for common features associated with cells that went on to develop tumours. Of all the features tested, only one was significantly linked to the development of a tumour: the number of cells containing the cancer-promoting gene within a tumour. For every additional cell in a cluster that contained a cancer-promoting gene, the odds of this cluster forming a tumour increased nine times.

In line with the modeling approach, when the team looked at the images of the acini, they found that cells that went on to establish tumours at the end of the four-day imaging period could be seen to cluster together at the start of the imaging period. By contrast, the cells that did not establish tumours were more sparsely located.

“Our results suggest that there is some interaction or signalling that occurs between malignant cells in close proximity that guides the initiation of a tumour within normal tissues,” concludes senior author Martin Jechlinger, Group Leader at EMBL. “Our ability to image the fate of these malignant single cells among healthy tissue means that it is now possible to follow tumour initiation, growth and treatment via inhibition by drugs in a realistic model, thereby helping to bridge the gap between model systems and the clinic.”

Media contacts

Emily Packer

eLife

e.packer@elifesciences.org

+441223855373

About

eLife is a non-profit organisation created by funders and led by researchers. Our mission is to accelerate discovery by operating a platform for research communication that encourages and recognises the most responsible behaviours. We work across three major areas: publishing, technology and research culture. We aim to publish work of the highest standards and importance in all areas of biology and medicine, including Cancer Biology and Cell Biology, while exploring creative new ways to improve how research is assessed and published. We also invest in open-source technology innovation to modernise the infrastructure for science publishing and improve online tools for sharing, using and interacting with new results. eLife receives financial support and strategic guidance from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Max Planck Society and Wellcome. Learn more at https://elifesciences.org/about.

To read the latest Cancer Biology research published in eLife, visit https://elifesciences.org/subjects/cancer-biology.

And for the latest in Cell Biology, see https://elifesciences.org/subjects/cell-biology.