Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

The paper develops a phase method to obtain the excitatory and inhibitory afferents to certain neuron populations in the brainstem. The inferred contributions are then compared to the results of voltage clamp and current clamp experiments measuring the synaptic contributions to post-I, aug-E, and ramp-I neurons.

Strengths:

The electrophysiology part of the paper is sound and reports novel features with respect to earlier work by JC Smith et al 2012, Paton et al 2022 (and others) who have mapped circuits of the respiratory central pattern generator. Measurements on ramp-I neurons, late-I neurons, and two types of post-I neurons in Figure 2 besides measurements of synaptic inputs to these neurons in Figure 5 are to my knowledge new.

Weaknesses:

The phase method for inferring synaptic conductances fails to convince. The method rests on many layers of assumptions and the inferred connections in Figure 4 remain speculative.

We hope that the additional method justifications now incorporated in the manuscript will make our method more convincing and change this reviewer’s opinion.

To be convincing, such a method ought to be tested first on a model CPG with known connectivity to assess how good it is at inferring known connections back from the analysis of spatio-temporal oscillations.

We respectfully disagree with this critique. Existing respiratory CPG models are based on a conductance-based formalism. Since the neurons recorded using our approach are typically hyperpolarized, in the model at the corresponding values of the membrane potential, all voltage-gated channels will be deactivated. Therefore, the current balance equation used in this study will closely align with the descriptions used in these models. This alignment will result in a near-exact correspondence between the synaptic conductance values inferred by our method and their model counterparts. However, we believe that such a demonstration, while predetermined to be successful, would not be convincing for a computationally savvy audience.

For biological data, once the network connectivity has been inferred as claimed, the straightforward validation is to reconstruct the experimental oscillations (Figure 2) noting that Rybak et al (Rybak, Paton Schwaber J. Neurophysiol. 77, 1994 (1997)) have already derived models for the respiratory neurons.

Running such simulations is beyond the scope of this paper, which focuses on our methods for extracting synaptic conductances during network activity cycles from intracellular recordings. However, the existing, largely speculative, respiratory CPG models can be validated against the "ground truth" of the inferences we present here. To illustrate how our circuit connection motifs elaborate on existing respiratory CPG models, we have now included a combinatorial connectivity model in the manuscript derived from the connectivity motifs in the supplemental figures (Figure 4 Supplemental Figure 1) with comparisons to the model schematic utilized by Rybak, Smith et al. in simulation studies to simulate a rhythmic three-phase respiratory pattern. There are conserved mechanistically important connectivity features between these schematics that it is possible to suggest that our more elaborate connectivity scheme would almost certainly generate the three-phase patterns of neuronal firing and network rhythmic activity.

The transformation from time to phase space, unlike in the Kuramoto model, is not justified here (Line 94) and is wrong. The underpinning idea that "the synaptic conductances depend on the cycle phase and not on time explicitly" is flawed because synapses have characteristic decay times and delays to response which remain fixed when the period of network oscillations increases. Synaptic properties depend on time and not on phase in the network.

The primary assumption of our method is that all variables within the system are periodic functions of time. Therefore, the inputs to the recorded neuron, at minimum, are fully defined by the oscillation's phase. While the transduction of the input into postsynaptic conductance may have its own time dependence, the characteristic timescale of synaptic dynamics (10-20 ms, as suggested by the reviewer) is much smaller than the period of network oscillations. This is certainly true for the test system we are using. This valid assumption of our method is now further clarified in the revised manuscript.

One major consequence relevant to the present identification of excitatory or inhibitory behaviour, is that it cannot account for change in the behaviour of inhibitory synapses - from inhibitory to excitatory action - when the inhibitory decay time becomes commensurable to the period of network oscillations (Wang & Buzsaki Journal of Neuroscience 16, 6402 (1996), van Vreeswijk et al. J. Comp. Neuroscience 1,313 (1994), Borgers and Kopell Neural Comput. 15, 2003).

Our method focuses on recovering synaptic conductances rather than directly measuring presynaptic inputs. The conversion of presynaptic inputs (spike trains) into postsynaptic conductances involves its own time scales. This can lead to complex dynamical effects when synaptic delay or decay times are comparable to the oscillation period. In such cases, although our conductance calculation remains accurate, we might misinterpret the phase of the presynaptic input, as it may not align with the phase of the postsynaptic conductance peak. However, this discrepancy is not significant for applications where the synaptic delay/decay times are considerably shorter than the oscillation period.

In addition, even small delays in the inhibitory synapse response relative to the pre-synaptic action potential also produce in-phase synchronization (Chauhan et al., Sci. Rep. 8, 11431 (2018); Borgers and Kopell, Neural Comput. 15, 509 (2003)).

The reviewer is referring to a phenomenon involving interspike synchronization that generates oscillations with very short periods, comparable to synaptic delay times. Our technique, in contrast, is designed for systems of asynchronously firing neurons forming functional populations whose oscillations emerge on a much longer time scale or are driven by periodic stimuli (e.g., sensory input) with a period much longer than the interspike intervals of individual neurons. The time scale difference we are addressing in our test system is two orders of magnitude.

The present assumptions are way too simplistic because you cannot account for these commensurability effects with a single parameter like the network phase. There is therefore little confidence that this model can reliably distinguish excitatory from inhibitory synapses when their dynamic properties are not properly taken into account.

As we explained in our previous responses, in our test system, we can reliably resolve post-synaptic conductance variations at 1/100th of the oscillation period. This is due to a >100X time scale difference between the oscillation period and the synaptic/membrane decay time constants. The efficiency of our method in other systems may vary depending on the relationship between the membrane time constant and the oscillation period. The text now provides a clearer discussion of the method's resolution.

To interpret post-synaptic conductance profiles in terms of presynaptic inputs (e.g., to reconstruct connectivity), one should consider the input-to-conductance transduction processes.We did not aim to provide a general solution for this step in our paper (hence the title) as these processes may differ for different neurotransmitter systems and involve individual dynamics. However, in our test system, as discussed, the oscillation period is much longer than the synaptic decay times of the fast-acting neurotransmitters involved (i.e., glutamate, glycine, and GABA). This means that the possible phase difference between presynaptic neuronal activity and the corresponding postsynaptic conductances is negligible. This allows for a straightforward interpretation of conductance profiles in terms of the functional connectivity of the network. In other systems, the situation may, of course, be different and additional efforts for inferring the presynaptic activity from postsynaptic conductance profiles may be necessary.

Line 82, Equation 1 makes extremely crude assumptions that the displacement current (CdV/dt) is negligible and that the ion channel currents are all negligible. Vm(t) is also not defined. The assumption that the activation/inactivation times of all ion channels are small compared to the 10-20ms decay time of synaptic currents is not true in general. Same for the displacement current. The leak conductance is typically g~0.05-0.09ms/cm^2 while C~1uF/cm^2. Therefore the ratio C/g leak is in the 10-20ms range - the same as the typical docking neurotransmitter time in synapses.

We have explicitly included capacitive current in the model formulation and described the time scale separation requirement that justifies our approach. Additionally, we now explain within the text that the current injection protocol involves hyperpolarizing the recorded neuron to ensure voltage-dependent currents remain deactivated during the recording. The remarkable linearity of the current-voltage relationships observed in the vast majority of recorded neurons provides post-hoc evidence supporting this assumption. For further details, please refer to our responses to Reviewer 2 and Figure 1 Supplemental Figure 1 as an example.

Models of brainstem CPG circuits have been known to exist for decades: JC Smith et al 2012, Paton et al 2022, Bellingham Clin. Exp. Pharm. And Physiol. 25, 847 (1998); Rubin et al., J. Neurophysiol. 101, 2146 (2009) among others. The present paper does not discuss existing knowledge on respiratory networks and gives the impression of reinventing the wheel from scratch. How will this paper add to existing knowledge?

We appreciate this comment, and in fact, in the original submitted version of this manuscript, we discussed existing knowledge of respiratory networks, but there was editorial concern that this material was above and beyond the technical aspects that we were trying to convey and therefore may detract from the paper as a technical submission. To strike a balance, we have re-incorporated some of this material in abbreviated form into the Discussion section “Implications of reconstructed synaptic conductance profiles for respiratory functional circuit architecture”.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

By measuring intracellular changes in membrane voltage from a single neuron of the medulla the authors describe a method for determining the balance of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic drive onto a single neuron within this important brain region.

Strengths:

This approach could be valuable in describing the microcircuits that generate rhythms within this respiratory control centre. This method could more generally be used to enable microcircuits to be studied without the need for time-consuming anatomical tracing or other more involved electrophysiological techniques.

Weaknesses:

This approach involves assuming the reversal potential that is associated with the different permeant ions that underlie the excitation and inhibition as well as the application of Ohms law to estimate the contribution of excitation and inhibitory conductance. My first concern is that this approach relies on a linear I-V relationship between the measured voltage and the estimated reversal potential. However, open rectification is a feature of any I-V relationship generated by asymmetric distributions of ions (see the GHK current equation) and will therefore be a particular issue for the inhibition resulting from asymmetrical Cl- ion gradients across GABA-A receptors. The mixed cation conductance that underlies most synaptic excitation will also generate a non-linear I-V relationship due to the inward rectification associated with the polyamine block of AMPA receptors. Could the authors please speculate what impact these non-linearities could have on results obtained using their approach?

In our Figure 1 Supplemental Figure 1, we illustrated that I-V relationships for each particular phase of the cycle (except for transitions between inspiration and expiration where our error estimates are greatest) are remarkably linear.

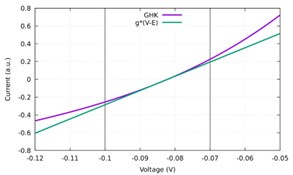

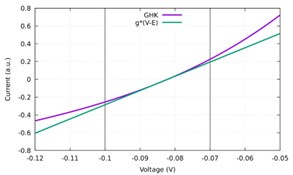

In Author response iamge 1 we compare the I-V dependence for Cl- as predicted by the GHK equation and its linear approximation using constant conductance and the Cl- Nernst potential. One can see that in the typical range of voltages used (shown by solid black vertical lines), the linear approximation appears quite adequate.

Author response image 1.

This approach has similarities to earlier studies undertaken in the visual cortex that estimated the excitatory and inhibitory synaptic conductance changes that contributed to membrane voltage changes during receptive field stimulation. However, these approaches also involved the recording of transmembrane current changes during visual stimulation that were undertaken in voltage-clamp at various command voltages to estimate the underlying conductance changes. Molkov et al have attempted to essentially deconvolve the underlying conductance changes without this information and I am concerned that this simply may not be possible.

This was why we compared the results of our reconstructions applied to current- and voltage-clamp recordings from the same neurons and we found, as illustrated, that the synaptic conductance profiles are qualitatively identical with both techniques.

The current balance equation (1) cited in this study is based on the parallel conductance model developed by Hodgkin & Huxley. However, one key element of the HH equations is the inclusion of an estimate of the capacitive current generated due to the change in voltage across the membrane capacitance. I would always consider this to be the most important motivation for the development of the voltage-clamp technique in the 1930's. Indeed, without subtraction of the membrane capacitance, it is not possible to isolate the transmembrane current in the way that previous studies have done. In the current study, I feel it is important that the voltage change due to capacitive currents is taken into consideration in some way before the contribution of the underlying conductance changes are inferred.

We have incorporated the capacitive current into the initial model formulation and established explicit requirements for time scale separation. These requirements justify the application of our method. Specifically, the membrane time constant (C/g ~ 10ms in our test system) must be substantially shorter than the period of network oscillations (T ~ 2s in our test system). Under this condition, aggregate variations in synaptic conductances can be considered slow, allowing us to treat membrane voltage as being in instantaneous equilibrium. This defines the time resolution of our method. Please refer to our responses to Reviewer 1 and the revised manuscript text for a more detailed explanation.

Studies using acute slicing preparations to examine circuit effects have often been limited to the study of small microcircuits - especially feedforward and feedback interneuron circuits. It is widely accepted that any information gained from this approach will always be compromised by the absence of patterned afferent input from outside the brain region being studied. In this study, descending control from the Pons and the neocortex will not be contributing much to the synaptic drive and ascending information from respiratory muscles will also be absent completely. This may not have been such a major concern if this study was limited to demonstrating the feasibility of a methodological approach. However, this limitation does need to be considered when using an approach of this type to speculate on the prevalence of specific circuit motifs within the medulla (Figure 4). Therefore, I would argue that some discussion of this limitation should be included in this manuscript.

Our experimental brainstem-spinal cord in situ preparation does include important inputs from the pons that are necessary to generate the 3-phase respiratory pattern (e.g., Smith et al. (2013). Brainstem respiratory networks: building blocks and microcircuits. Trends Neurosci, 36(3), 152-162), but we agree that other inputs such as from midbrain and cortex as well as important peripheral afferents are absent, and we have now noted this limitation in the text at the end of the new section “Implications of reconstructed synaptic conductance profiles for respiratory functional circuit architecture“. We show specific circuit motifs simply to illustrate how our readout of synaptic conductances from single neurons and the information on the main neuronal activity patterns in our experimental preparation can be interpreted. We thought that it would be useful to illustrate and interpret inferred connectivity motifs as an output of our methodological approach. As we now discuss in the section “Implications of reconstructed synaptic conductance profiles for respiratory functional circuit architecture” in response to Reviewer #1, our circuit motifs are consistent with some sets of connections that have been speculated in the literature, but they also provide some novel information about connectivity that we have been able to infer for respiratory circuits from the complex sets of synaptic conductances indicated by our approach.

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for the authors):

Major comments:

(1) My recommendation is to clarify how each neuron population was identified. Individual populations are very hard to identify based on morphology alone in brain slices such as Supplemental Figure 1. I assume the authors identified each population based on their phase difference relative to the inspiratory pulse in the phrenic nerve. This ought to be clarified.

Neuronal populations were classified based on their firing patterns within the respiratory cycle. Immunohistochemistry was only used for post-hoc identification of the transmitter phenotype in select neurons. Specifically, recorded neurons were categorized according to the phase range of the respiratory cycle in which they fired and their firing pattern during that range. For example, neurons firing during inspiration (synchronously with the phrenic nerve) with a progressively increasing firing rate were classified as ramp-I, etc., as illustrated in the figure depicting phase-dependent firing patterns. This classification is detailed in the "Firing patterns of respiratory interneurons" sub-section.

It would also be beneficial to discuss the benefits and limitations of using this preparation relative to brainstem slices and in-vivo preparations (e.g. Moraes et al. J. Physiol. 599, 3237 (2021)) for measuring live network activity.

We provided the reference to an important recent review (Paton et al. 2022, Advancing respiratory-cardiovascular physiology with the working heart-brainstem preparation over 25 years. J Physiol, 600(9), 2049-2075) on the benefits and limitations of using the in situ rodent brainstem-spinal cord preparation employed in our study.

(2) The background on inference methods is similarly thin. The works in line 47 are mainly experimental characterizations of excitatory and inhibitory cells. Techniques for estimating network conductances/parameters ought to be covered. One reference that comes to mind: Armstrong, E. Statistical data assimilation for estimating electrophysiology simultaneously with connectivity within a biological neuronal network. Physical Review E 101, 012415, 2020.

Our technique is not intended to estimate synaptic connections between neurons from paired recordings. Instead, we calculate the dynamics of inhibitory and excitatory synaptic conductances that result from many concurrent synaptic inputs representing aggregate activities of the functionally interacting populations. The previous studies that we cited are the ones that have direct or indirect relation to this paradigm.

(3) How the "patterns of synaptic conductances" in phase diagrams imply the network connectivity (l.244) is not clear. Are the patterns of "activity patterns" depicted in Figure 2 the only neuron populations driving the postsynaptic neurons in Figure 4?

Figure 2 shows all of the basic firing patterns that we have recorded in our experimental preparation. So, yes, assuming that all periodic inputs in this network originate from within the network, those 6 populations are the main sources of the corresponding patterns.

The methodology for constructing the networks is unclear,

This is explained in detail in the section "Synaptic Conductances and Functional Connectome of Respiratory Interneurons". Specifically, when a neuron with a given firing pattern (and thus belonging to a corresponding population, e.g., pre-I/I) exhibits excitatory or inhibitory conductance during a particular phase of the respiratory cycle (e.g., inhibition during the first half of expiration, as in Figure 3A1), we infer that the population with the same firing pattern receives input from a population with an activity pattern matching the postsynaptic conductance profile (e.g., the pre-I/I population receives post-I inhibition, as in Figure 4A1).

yet 6 lines later (l.251) the narrative jumps to the conclusion that "the information on inhibitory transmitter phenotypes...indeed corroborates that subsets of the presynaptic neurons are inhibitory" and further "conductance profiles, which gives additional confidence in the correlation between pre-synaptic firing patterns and likely post-synaptic interactions". The method also blends in empirical information from immune labelling. It is unclear what method can actually infer on its own.

The functional connections that we were able to infer implied that neurons with specific firing patterns (e.g., post-I neurons) must include neurons with specific transmitter phenotypes (e.g., inhibitory). Immune labeling results were used to show that there are indeed neurons having corresponding firing patterns and neurotransmitter phenotypes. It has nothing to do with the inference method. It just shows that our assumption about various inhibitory inputs originating from within the network is plausible.

(4) Figure 3 - why does the Early-I population which is connected by the same mutually inhibitory links as Post-I and Aug-E within the respiratory CPG have the opposite conductance activation sequence as post-I and aug-E. Namely, it receives excitatory input at phases 0,1,2 when post-I and aug-E receive inhibitory input?

We added the section “Implications of reconstructed synaptic conductance profiles for respiratory functional circuit architecture” discussing the correspondence and inconsistencies between our findings and existing respiratory CPG models (see Figure 4 Supplemenntal Figure 1). For this specific question, phase 0, 1 and 2 represent the same phase of the respiratory cycle corresponding to a transition from expiration to inspiration. According to the Rybak et al. models, the early-I population receives excitation from the pre-I/I population which is active at the E-I transition and throughout the entire inspiratory phase of the cycle. This is largely consistent with our findings shown in Figure 3. Also, according to Rybak et al., post-I and aug-E populations are inhibited by early-I neurons, which is also consistent with inspiratory inhibition in all examples of these neurons that we show in Figure 3. As noted in other responses to the reviewers’ comments, we have now discussed in the “Implications of reconstructed synaptic conductance profiles for respiratory functional circuit architecture” which covers some comparisons to previously inferred connectivity in the respiratory network.

Minor comments:

(1) l.39 - The terminology "patterns of inhibitory and excitatory synaptic conductances" used throughout the manuscript (l.66, 241, 244, 259...) is vague.

We defined this terminology in the updated version.

(2) Figure 1 what is the integration time of the moving median in Figure 1a?

0.1s. Now included in the figure legend.

(3) L.128 "rhythmic inspiratory neuron" which one is this post-I, aug-E, early-I?

This example demonstrates a pre-I/I firing pattern, as the neuron begins firing slightly before the phrenic burst and continues throughout inspiration (as defined by phrenic nerve activity). However, this is merely an arbitrary example used to illustrate the methodology. The actual firing pattern of the recorded neuron is not considered in any way for synaptic conductance inference.

(4) Figure 3 What the panel labelling means A1, B1, A2, etc. is not disclosed in the caption.

These labels are used in the text to refer to specific examples. Now it is explained in the caption that the letter corresponds to the firing phenotype indicated on the top of each column and the digit refers to the example number.

(5) L.129/ L.133 - the diagram of the medulla in Supplementary Figure 1 ought to be inserted early on in the main text when introducing the respiratory CPG, phrenic and vagal signals.

This is a good suggestion and we have linked this figure specifically to Figure 2 as Figure 2 Supplemental Figure 1 in the main text to better orient readers.

(6) L. 457 - Reference needed on reversal potentials.

We report what we observed, so it is unclear what reference the reviewer means.