Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Reviewer #1:

Summary:

The manuscript by Bohra et al. describes the indirect effects of ligand-dependent gene activation on neighboring non-target genes. The authors utilized single-molecule RNA-FISH (targeting both mature and intronic regions), 4C-seq, and enhancer deletions to demonstrate that the non-enhancer-targeted gene TFF3, located in the same TAD as the target gene TFF1, alters its expression when TFF1 expression declines at the end of the estrogen signaling peak. Since the enhancer does not loop with TFF3, the authors conclude that mechanisms other than estrogen receptor or enhancer-driven induction are responsible for TFF3 expression. Moreover, ERα intensity correlations show that both high and low levels of ERα are unfavorable for TFF1 expression. The ERa level correlations are further supported by overexpression of GFP-ERa. The authors conclude that transcriptional machinery used by TFF1 for its acute activation can negatively impact the TFF3 at peak of signaling but once, the condensate dissolves, TFF3 benefits from it for its low expression.

Strengths:

The findings are indeed intriguing. The authors have maintained appropriate experimental controls, and their conclusions are well-supported by the data.

Weaknesses:

There are some major and minor concerns that related to approach, data presentation and discussion. But I think they can be fixed with more efforts.

We thank the reviewer for their positive comments on the paper. We have addressed all their specific recommendations below.

The deletion of enhancer reveals the absolute reliance of TFF1 on its enhancers for its expression. Authors should elaborate more on this as this is an important finding.

We thank the reviewer for the comment. We have now added a more detailed discussion on the requirement of enhancer for TFF1 expression in the revised manuscript (line 368-385).

In Fig. 1, TFF3 expression is shown to be induced upon E2 signaling through qRT-PCR, while smFISH does not display a similar pattern. The authors attribute this discrepancy to the overall low expression of TFF3. In my opinion, this argument could be further supported by relevant literature, if available. Additionally, does GRO-seq data reveal any changes in TFF3 expression following estrogen stimulation? The GRO-seq track shown in Fig.1 should be adjusted to TFF3 expression to appreciate its expression changes.

We have now included a browser shot image of TFF3 region showing GRO-Seq signal at E2 time course (Fig. S1C). We observed an increased transcription towards the 3’ end of TFF3 gene body at 3h. The increased transcription at 3h, corroborates with smFISH data. The relative changes of TFF3 expression measured by qRT-PCR and smFISH for intronic transcripts are somewhat different, we speculate that such biased measurements that are dependent on PCR amplifications could be more for genes that express at low levels and smFISH using intronic probes may be a more sensitive assay to detect such changes.

Since the mutually exclusive relationship between TFF1 and TFF3 is based on snap shots in fixed cells, can authors comment on whether the same cell that expresses TFF1 at 1h, expresses TFF3 at 3h? Perhaps, the calculations taking total number of cells that express these genes at 1 and 3h would be useful.

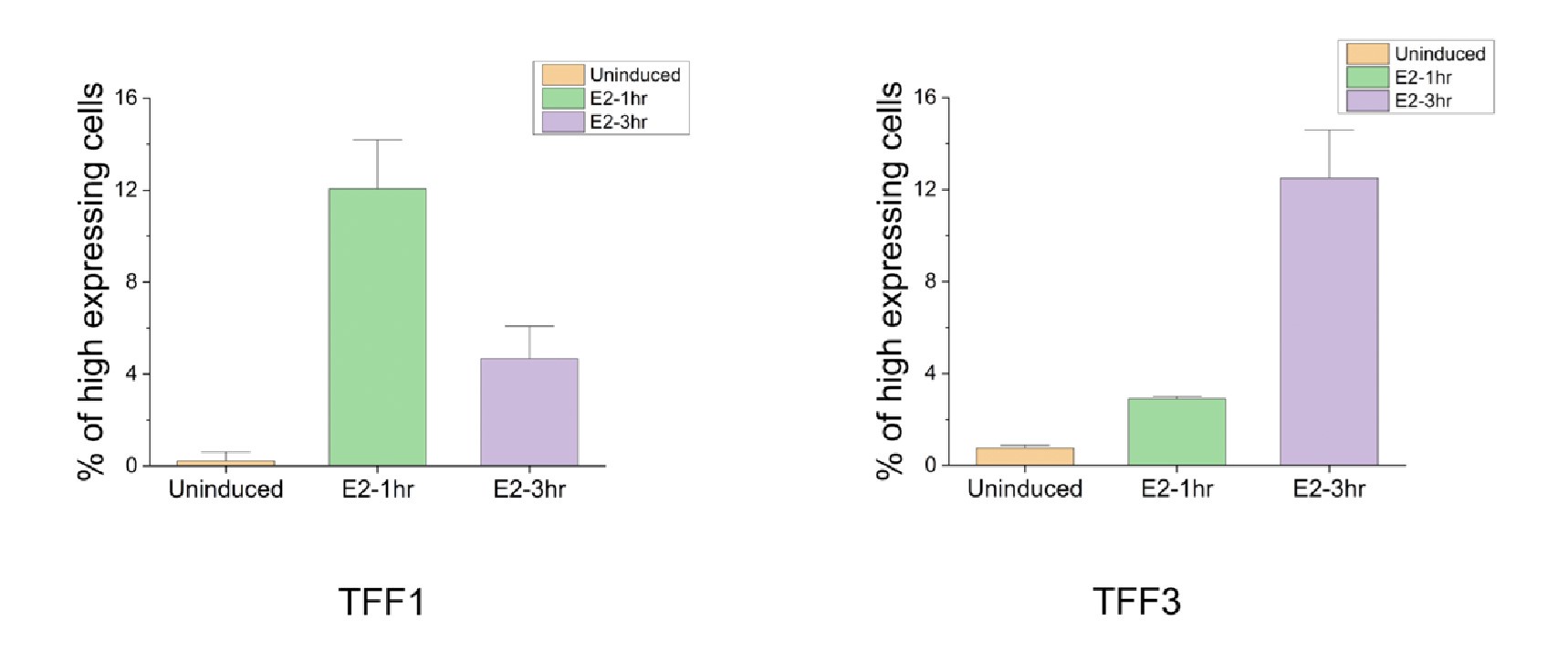

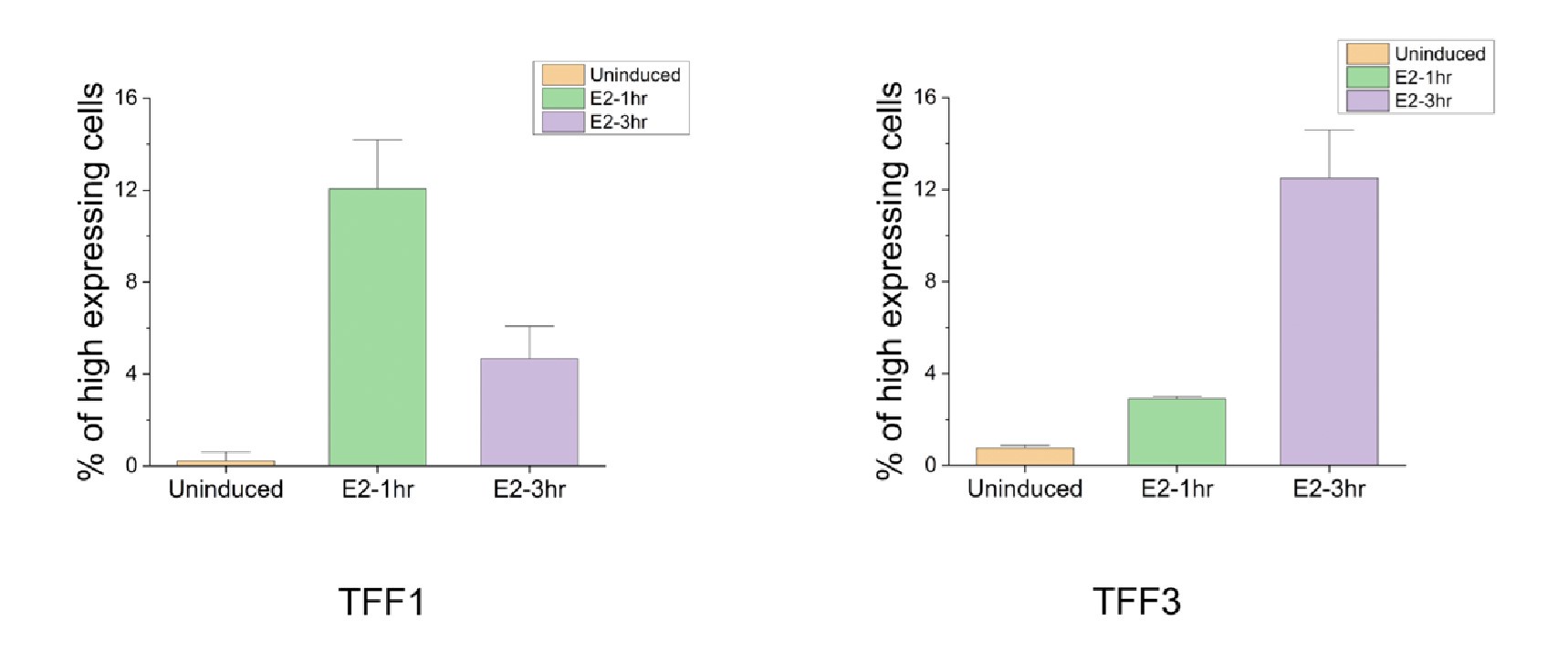

Like pointed out by the reviewer, since these are fixed cells, we cannot comment on the fate of the same cell at two time points. To further address this limitation, future work could employ cells with endogenous tags for TFF1 and TFF3 and utilize live cell imaging techniques. In a fixed cell assay, as the reviewer suggests, it can be investigated whether a similar fraction shows high TFF3 expression at 3h, as the fraction that shows high TFF1 expression at 1 h. To quantify the fractions as suggested by the reviewer, we plotted the fraction of cells showing high TFF1 and TFF3 expression at 1h and 3h. We identify truly high expressing cells by taking mean and one standard deviation (for single cell level data) at E2-1hr as the threshold for TFF1 (80 and above transcript counts) and mean and one standard deviation (for single cell level data) at E2-3hr as the threshold for TFF3 (36 and above transcript counts). The fraction with high TFF1 expression at 1h (12.06 ± 2.1) is indeed comparable to that with high TFF3 expression at 3h (12.50 ± 2.0) (Fig. 2C and Author response image 1). We should note that if the transcript counts were normally distributed, a predetermined fraction would be expected to be above these thresholds and comparable fractions can arise just from underlying statistics. But in our experiments, this is unlikely to be the case given the many outliers that affect both the mean and the standard deviation, and the lack of normality and high dispersion in single cell distributions. Of course, despite the fractions being comparable, we cannot be certain if it is the same set of cells that go from high expression of TFF1 to high expression of TFF3, but definitely that is a possibility. We thank the reviewer for pointing out this comparison.

Author response image 1.

The graph represents the percent of cells that show high expression for TFF1 and TFF3 at 1h and 3h post E2 signaling. The threshold was collected by pooling in absolute RNA counts from 650 analyzed cells (as in Fig. 2C). The mean and standard deviation over single cell data were calculated. Mean plus one standard deviation was used to set the threshold for identifying high expressing cells. For TFF1, as it maximally expresses at 1h the threshold used was 80. For TFF3, as it maximally expresses at 3h the threshold used was 36. Fraction of cells expressing above 80 and 36 for TFF1 and TFF3 respectively were calculated from three different repeats. Mean of means and standard deviations from the three experiments are plotted here.

Authors conclude that TFF3 is not directly regulated by enhancer or estrogen receptor. Does ERa bind on TFF3 promoter?

The ERa ChIP-seq performed at 1h and 3h of signaling suggests that TFF3 promoter is not bound by ERa as shown in supplementary Fig. 1B and S1B. However, one peak upstream to TFF1 promoter is visible and that is lost at 3h.

Minor comments:

Reviewer’s comment -The figures would benefit from resizing of panels. There is very little space between the panels.

We have now resized the figures in the revised manuscript.

The discussion section could include an extrapolation on the relationship between ERα concentration and transcriptional regulation. Given that ERα levels have been shown to play a critical role in breast cancer, exploring how varying concentrations of ERα affect gene expression, including the differential regulation of target and non-target genes, would provide valuable insights into the broader implications of this study.

This is a very important point that was missing from the manuscript. We have included this in the discussion in the revised manuscript (line 426-430).

Reviewer #2:

Summary:

In this manuscript by Bohra et al., the authors use the well-established estrogen response in MCF7 cells to interrogate the role of genome architecture, enhancers, and estrogen receptor concentration in transcriptional regulation. They propose there is competition between the genes TFF1 and TFF3 which is mediated by transcriptional condensates. This reviewer does not find these claims persuasive as presented. Moreover, the results are not placed in the context of current knowledge.

Strengths:

High level of ERalpha expression seems to diminish the transcriptional response. Thus, the results in Fig. 4 have potential insight into ER-mediated transcription. Yet, this observation is not pursued in great depth however, for example with mutagenesis of ERalpha. However, this phenomenon - which falls under the general description of non monotonic dose response - is treated at great depth in the literature (i.e. PMID: 22419778). For example, the result the authors describe in Fig. 4 has been reported and in fact mathematically modeled in PMID 23134774. One possible avenue for improving this paper would be to dig into this result at the single-cell level using deletion mutants of ERalpha or by perturbing co-activators.

We thank the reviewer for pointing us to the relevant literature on our observation which will enhance the manuscript. We have discussed these findings in relations to ours in the discussion section (Line 400-413). We thank the reviewer for insight on non-monotonic behavior.

Weaknesses:

There are concerns with the sm-RNA FISH experiments. It is highly unusual to see so much intronic signal away from the site of transcription (Fig. 2) (PMID: 27932455, 30554876), which suggests to me the authors are carrying out incorrect thresholding or have a substantial amount of labelling background. The Cote paper cited in the manuscript is likewise inconsistent with their findings and is cited in a misleading manner: they see splicing within a very small region away from the site of transcription.

We thank the reviewer for this comment, and apologize if they feel we misrepresented the argument from Cote et al. This has now been rectified in the manuscript. However, we do not agree that the intronic signals away from the site of transcription are an artefact. First, the images presented here are just representative 2D projections of 3D Z-stacks; whereas the full 3D stack is used for spot counting using a widely-used algorithm that reports spot counts that are constant over wide range of thresholds (Raj et al., 2008). The veracity of automated counts was first verified initially by comparison to manual counts. Even for the 2D representations the extragenic intronic signals show up at similar thresholds to the transcription sites.

The signal is not non-specific arising from background labeling, explained by following reasons:

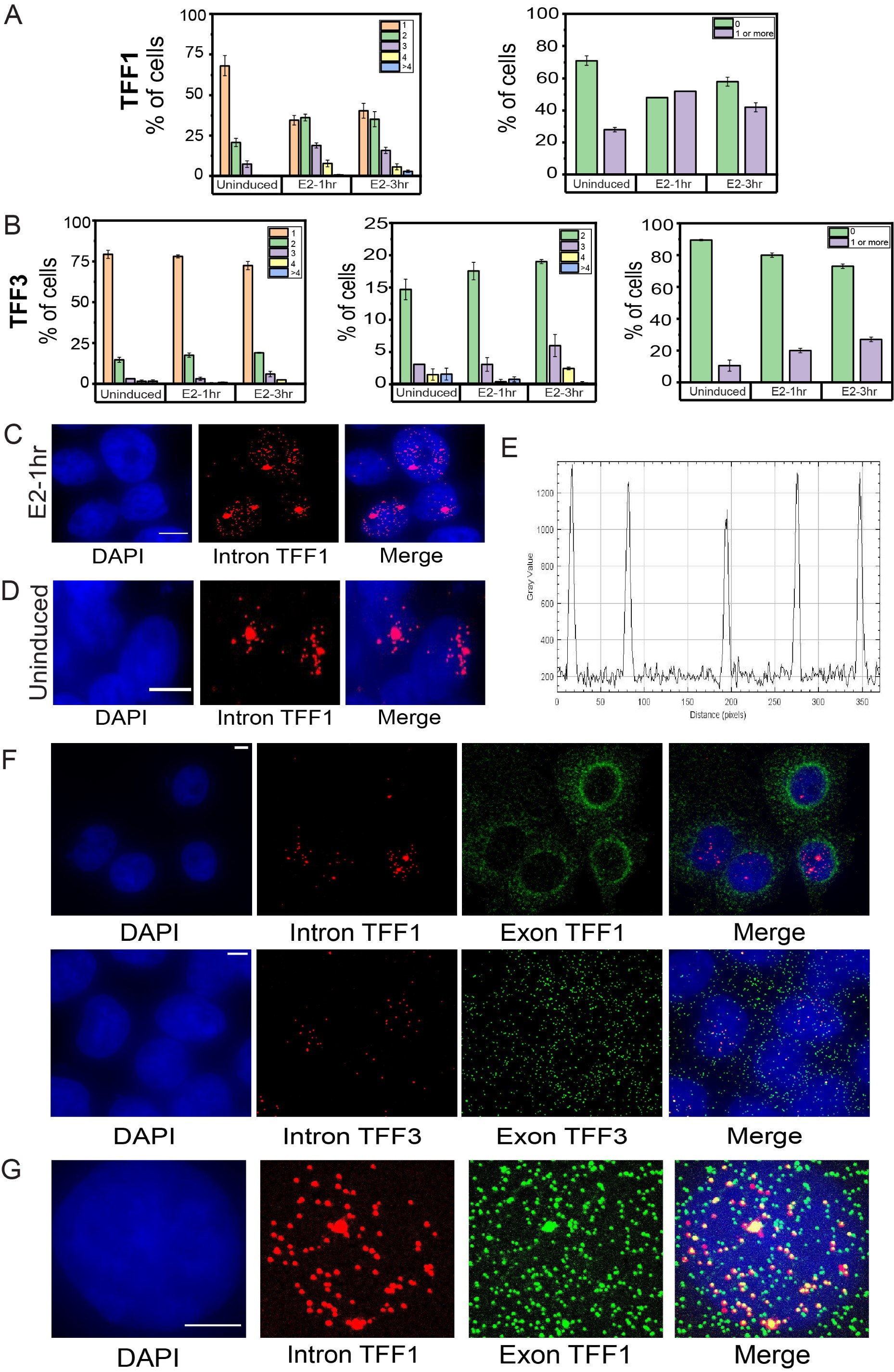

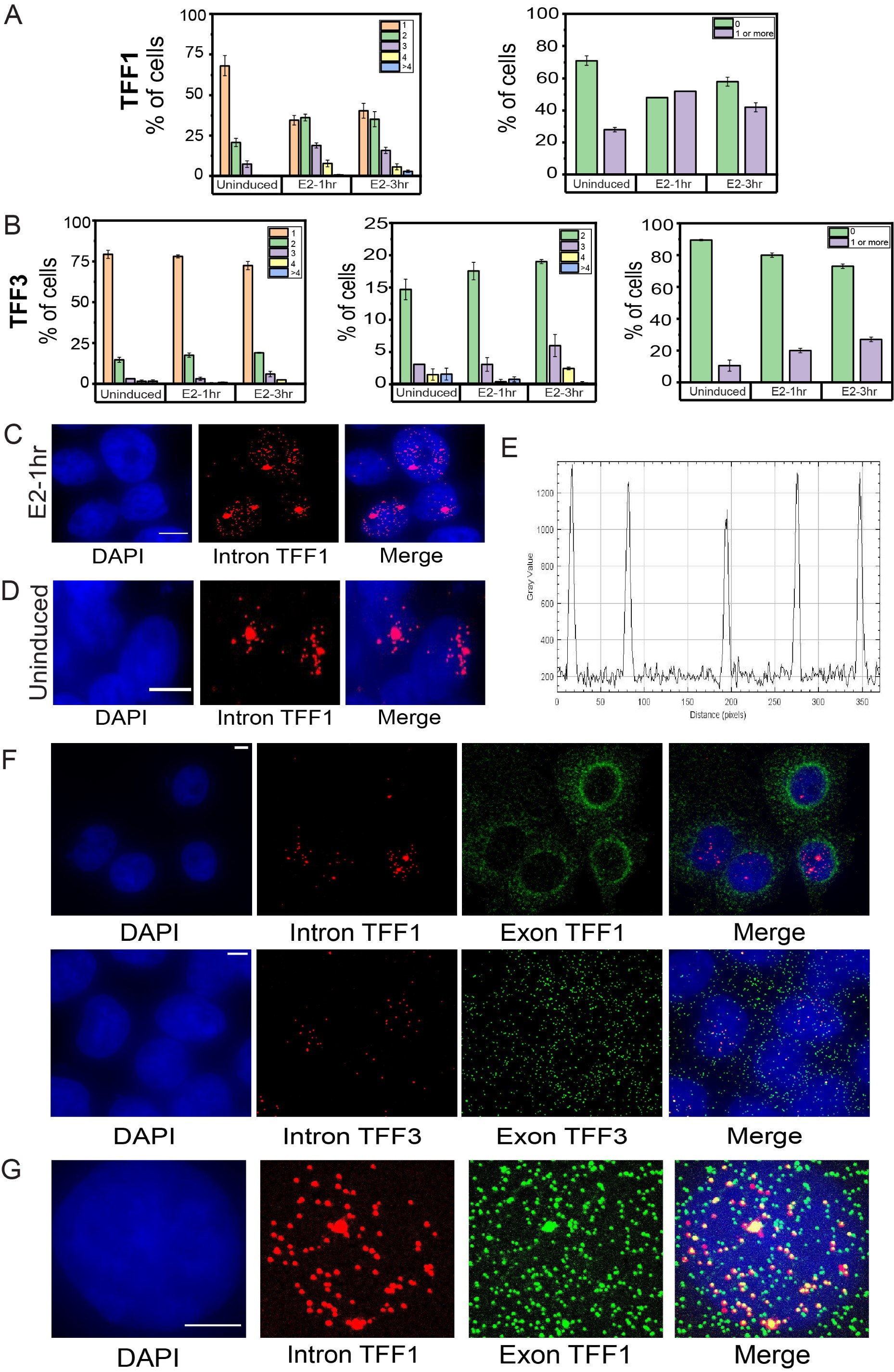

• To further support the time-course smFISH data and its interpretation without depending on the dispersed intronic signal, we have analyzed the number of alleles firing/site of transcription at a given time in a cell under the three conditions. We counted the sites of transcription in a given cell and calculated the percentage of cells showing 1,2,3,4 or >4 sites. We see that the percent of cells showing a single site of transcription for TFF1 is very high in uninduced cells and this decreases at 1h. At 1h, the cells showing 2, 3 and 4 sites of transcription increase which again goes down at 3h (Author response image 2A). This agrees with the interpretation made from mean intronic counts away from the site of transcription. Similarly, for TFF3, the number of cells showing 2,3 and 4 sites of transcription increase slightly at 3hr compared to uninduced and 1hr (Author response image 2B). We can also see that several cells have no alleles firing at a given time as has been quantified in the graphs on right showing total fraction of cells with zero versus non-zero alleles firing (Author response image 2A-B). A non-specific signal would be present in all cells.

• There is literature on post-transcriptional splicing of RNA beyond our work, which suggests that intronic signal can be found at relatively large distances away from the site of transcription. Waks et al. showed that some fraction of unspliced RNA could be observed up to 6-10 microns away from the site of transcription suggesting that there can be a delay between transcription and (alternative) splicing (Waks et al., 2011). Pannuclear disperse intronic signals can arise as there can be more than one allele firing at a time in different nuclear locations. The spread of intronic transcripts in our images is also limited in cells in which only 1 allele is firing at E2-1 hour (Author response image 2C) or uninduced cells (Author response image 2D). Furthermore, Cote et al. discuss that “Of note, we see that increased transcription level correlates with intron dispersal, suggesting that the percentage of splicing occurring away from the transcription site is regulated by transcription level for at least some introns. This may explain why we observe posttranscriptional splicing of all genes we measured, as all were highly expressed.” This is in line with our interpretation that intron signal dispersal can occur in case of posttranscriptional splicing (Coté et al., 2023). Additionally, other studies have suggested that transcripts in cells do not necessarily undergo co-transcriptional splicing which leads us to conclude that intronic signal can be found farther away from the site of transcription. Coulon et al. showed that splicing can occur after transcript release from the site and suggested that no strict checkpoint exists to ensure intron removal before release which results in splicing and release being kinetically uncoupled from each other (Coulon et al., 2014). Similarly, using live-cell imaging, it was shown that splicing is not always coupled with transcription, and this could depend on the nature and structural features of transcript (such as blockage of polypyrimidine tract which results in delayed recognition) (Vargas et al., 2011). Drexler et al. showed that as opposed to drosophila transcripts that are shorter, in mammalian cells, splicing of the terminal intron can occur post-transcriptionally (Drexler et al., 2020). Using RNA polymerase II ChIP-Seq time course data from ERα activation in the MCF-7 cells, Honkela et al. showed that large number of genes can show significant delays between the completion of transcription and mRNA production (Honkela et al., 2015). This was attributed to faster transcription of shorter genes which results in splicing delays suggesting rapid completion of transcription on shorter genes can lead to splicing-associated delays (Honkela et al., 2015). More recently, comparisons of nascent and mature RNA levels suggested a time lapse between transcription and splicing for the genes that are early responders during signaling (Zambrano et al., 2020). The presence of significant numbers of TFF1 nascent RNA in the nucleus in our data corroborates with above observations.

• Uniform intensities across many transcripts suggests these are true signal arising from RNA molecules which would not be the case for non-specific, background signal (Author response image 2E).

• Splicing occurs in the nucleus and intron containing pre-transcripts should be nuclear localized. Thus, intronic signals should remain localized to the nucleus unlike the mature mRNA which translocate to the cytoplasm after processing and thus exonic signals can be found both in the nucleus and the cytoplasm. In keeping with this, we observe no signal in the cytoplasm for the intronic probes and it remains localized within the nucleus as expected and can be seen in Author response image 2F, while exonic signals are observed in both compartments. This suggests to us that the signal is coming from true pre-transcripts. There is no reason for non-specific background labelling to remain restricted to the nucleus.

• We observe that the mean intronic label counts for both the genes TFF1 and TFF3 increases upon E2-induction compared to uninduced condition (Fig. 2B). Similarly, the mean intronic count for both genes reduce drastically in the TFF1-enhancer deleted cells (Fig. 3C, D). This change in the number of intronic signal specifically on induction and enhancer deletion suggests that the signal is not an artefact and arises from true nascent transcripts that are sensitive to stimulus or enhancer deletion.

• We expect colocalization of intronic signal with exonic signals in the nucleus, while there can be exonic signals that do not colocalize with intronic, representing more mature mRNA. Indeed, we observe a clear colocalization between the intronic and exonic signals in the nucleus, while exonic signals can occur independent of intronic both in the nucleus and the cytoplasm. This clearly demonstrates that the intronic signals in our experiments are specific and not simply background labelling (Author response image 2G).

These studies and the arguments above lead us to conclude that the presence of intronic transcripts in the nucleus, away from the site of transcription is not an artefact. We hope the reviewer will agree with us. These analyses have now been included in the manuscript as Supplementary Figure 6 and have been added in the manuscript at line numbers 106-111, 201204, 215-217 and line 231-235. We thank the reviewer for raising this important point.

Author response image 2.

Dynamic induction and RNA localization of TFF1 and TFF3 transcription across cell populations using smRNA FISH A. Bar graph depicting the percentage of cells with 1,2,3,4, or greater than 4 sites of transcription for TFF1 (left) is shown. The graph shows the mean of means from different repeats of the experiment, and error bars denote SEM (n>200, N=3). Only the cells with at least one allele firing were counted and cells with no alleles were not included in this. The graph on right shows the number of cells with zero or non-zero number of alleles firing. B. Bar graph depicting the percentage of cells with 1,2,3,4 or greater than 4 sites of transcription for TFF3 (left) is shown. The graph shows the mean of means from different repeats of the experiment, and error bars denote SEM (n>200, N=3). Only the cells with at least one allele firing were counted and cells with no alleles were not included in this. The graph in the middle shows the number of cells with 2,3,4 or greater than 4 sites of transcription for TFF3.The graph on the right shows the number of cells with zero or non-zero number of alleles firing. C. Images from single molecule RNA FISH experiment showing transcripts for InTFF1 in cells induced for 1 hour with E2. The image shows that when a single allele of TFF1 is firing, the transcripts show a more spatially restricted localisation. The scale bar is 5 microns. D. Images from single molecule RNA FISH experiment showing transcripts for InTFF1 in uninduced cells. The image shows that when a single allele of TFF1 is firing and transcription is low, the transcripts show a more spatially restricted localisation. The scale bar is 5 microns. E. Line profile through several transcripts in the nucleus show uniform and similar intensities indicating that these are true signals. F. 60X Representative images from a single molecule RNA FISH experiment showing transcripts for InTFF1 and ExTFF1 (top) and InTFF3 and ExTFF3 (bottom). The image shows that there is no intronic signal in the cytoplasm, while exonic signals can be found both in the nucleus and the cytoplasm. The scale bar is 5 microns. G. 60X Representative images from single molecule RNA FISH experiment showing transcripts for InTFF1 and ExTFF1. The image shows that all intronic signals are colocalized with exonic signals, but all exonic signals are expectedly not colocalized with intronic signals, representing more mature mRNA. The scale bar is 5 microns.

One substantial way to improve the manuscript is to take a careful look at previous single cell analysis of the estrogen response, which in some cases has been done on the exact same genes (PMID: 29476006, 35081348, 30554876, 31930333). In some of these cases, the authors reach different conclusions than those presented in the present manuscript. Likewise, there have been more than a few studies that have characterized these enhancers (the first one I know of is: PMID 18728018). Also, Oh et al. 2021 (cited in the manuscript) did show an interaction between TFF1e and TFF3, which seems to contradict the conclusion from Fig. 3. In summary, the results of this paper are not in dialogue with the field, which is a major shortcoming.

We thank the reviewer for pointing out these important studies. The studies from Prof. Larson group are particularly very insightful (Rodriguez et al., 2019). We have now included this in the discussion (line 106-111 and line 420-424) where we suggest the differences and similarities between our, Larson’s group and also Mancini’s group (Patange et al., 2022; Stossi et al., 2020).

The 4C-Seq data from the manuscript Oh et al. 2021 is exactly consistent with our observation from Fig 3 as they also observed little to no interaction between TFF1e and TFF3p in WT cells, only upon TFF1p deletion, did the TFF1e become engaged with the TFF3p. In agreement with this, we also observe little to no interaction between TFF1e and TFF3p in WT cells (Fig.3A). This is also consistent with our competition model for resources between these two genes. Oh et al. shows interaction between TFF1e and TFF3 when the TFF1 promoter is deleted showing that when the primary promoter is not available the enhancer is retargeted to the next available gene (Oh et al., 2021). It does not show that in WT or at any time point of E2 signalling does TFF1e and TFF3 interact.

In the opinion of this reviewer, there are few - if any - experiments to interrogate the existence of LLPS for diffraction-limited spots such as those associated with transcription. This difficulty is a general problem with the field and not specific to the present manuscript. For example, transient binding will also appear as a dynamic 'spot' in the nucleus, independently of any higher-order interactions. As for Fig. 5, I don't think treating cells with 1,6 hexanediol is any longer considered a credible experiment. For example, there are profound effects on chromatin independent of changes in LLPS (PMID: 33536240).

We are cognizant of and appreciate the limitations pointed out by the reviewer. We and others have previously shown that ERa forms condensates on TFF1 chromatin region using ImmunoFISH assay (Saravanan et al., 2020). The data below shows the relative mean ERα intensity on TFF1 FISH spots and random regions clearly showing an appearance of the condensate at the TFF1 site. Further, the deletion of TFF1e causes the reduction in size of this condensate. Thus, we expect that these ERα condensates are characterized by higher-order interactions and become disrupted on treatment with 1,6-hexanediol. These condensates are the size of below micron as mentioned by the reviewer, but most TF condensates are of the similar sizes. We agree with the reviewer that 1,6- hexanediol treatment is a brute-force experiment with several irreversible changes to the chromatin. Although we have tried to use it at a low concentration for a short period of time and it has been used in several papers (Chen et al., 2023; Gamliel et al., 2022). The opposite pattern of TFF1 vs. TFF3 expression upon 1,6- hexanediol treatment suggests that there is specificity. Further, to perturb condensates, mutants of ERa can be used (N-terminus IDR truncations) however, the transcriptional response of these mutants is also altered due to perturbed recruitment of coactivators that recognize Nterminus of ER, restricting the distinction between ERa functions and condensate formation.

References:

Chen, L., Zhang, Z., Han, Q., Maity, B. K., Rodrigues, L., Zboril, E., Adhikari, R., Ko, S.-H., Li, X., Yoshida, S. R., Xue, P., Smith, E., Xu, K., Wang, Q., Huang, T. H.-M., Chong, S., & Liu, Z. (2023). Hormone-induced enhancer assembly requires an optimal level of hormone receptor multivalent interactions. Molecular Cell, 83(19), 3438-3456.e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2023.08.027

Coté, A., O’Farrell, A., Dardani, I., Dunagin, M., Coté, C., Wan, Y., Bayatpour, S., Drexler, H. L., Alexander, K. A., Chen, F., Wassie, A. T., Patel, R., Pham, K., Boyden, E. S., Berger, S., Phillips-Cremins, J., Churchman, L. S., & Raj, A. (2023). Post-transcriptional splicing can occur in a slow-moving zone around the gene. eLife, 12. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.91357.2

Coulon, A., Ferguson, M. L., de Turris, V., Palangat, M., Chow, C. C., & Larson, D. R. (2014). Kinetic competition during the transcription cycle results in stochastic RNA processing. eLife, 3, e03939. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.03939

Drexler, H. L., Choquet, K., & Churchman, L. S. (2020). Splicing Kinetics and Coordination Revealed by Direct Nascent RNA Sequencing through Nanopores. Molecular Cell, 77(5), 985-998.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2019.11.017

Gamliel, A., Meluzzi, D., Oh, S., Jiang, N., Destici, E., Rosenfeld, M. G., & Nair, S. J. (2022). Long-distance association of topological boundaries through nuclear condensates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 119(32), e2206216119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2206216119

Honkela, A., Peltonen, J., Topa, H., Charapitsa, I., Matarese, F., Grote, K., Stunnenberg, H. G., Reid, G., Lawrence, N. D., & Rattray, M. (2015). Genome-wide modeling of transcription kinetics reveals patterns of RNA production delays. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(42), 13115. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1420404112

Oh, S., Shao, J., Mitra, J., Xiong, F., D’Antonio, M., Wang, R., Garcia-Bassets, I., Ma, Q., Zhu, X., Lee, J.-H., Nair, S. J., Yang, F., Ohgi, K., Frazer, K. A., Zhang, Z. D., Li, W., & Rosenfeld, M. G. (2021). Enhancer release and retargeting activates disease-susceptibility genes. Nature, 595(7869), Article 7869. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03577-1

Patange, S., Ball, D. A., Wan, Y., Karpova, T. S., Girvan, M., Levens, D., & Larson, D. R. (2022). MYC amplifies gene expression through global changes in transcription factor dynamics. Cell Reports, 38(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.110292

Raj, A., van den Bogaard, P., Rifkin, S. A., van Oudenaarden, A., & Tyagi, S. (2008). Imaging individual mRNA molecules using multiple singly labeled probes. Nature Methods, 5(10), Article 10. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1253

Rodriguez, J., Ren, G., Day, C. R., Zhao, K., Chow, C. C., & Larson, D. R. (2019). Intrinsic Dynamics of a Human Gene Reveal the Basis of Expression Heterogeneity. Cell, 176(1–2), 213-226.e18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.026

Saravanan, B., Soota, D., Islam, Z., Majumdar, S., Mann, R., Meel, S., Farooq, U., Walavalkar, K., Gayen, S., Singh, A. K., Hannenhalli, S., & Notani, D. (2020). Ligand dependent gene regulation by transient ERα clustered enhancers. PLOS Genetics, 16(1), e1008516. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1008516

Stossi, F., Dandekar, R. D., Mancini, M. G., Gu, G., Fuqua, S. A. W., Nardone, A., De Angelis, C., Fu, X., Schiff, R., Bedford, M. T., Xu, W., Johansson, H. E., Stephan, C. C., & Mancini, M. A. (2020). Estrogeninduced transcription at individual alleles is independent of receptor level and active conformation but can be modulated by coactivators activity. Nucleic Acids Research, 48(4), 1800. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz1172

Vargas, D. Y., Shah, K., Batish, M., Levandoski, M., Sinha, S., Marras, S. A. E., Schedl, P., & Tyagi, S. (2011). Single-Molecule Imaging of Transcriptionally Coupled and Uncoupled Splicing. Cell, 147(5), 1054–1065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.024

Waks, Z., Klein, A. M., & Silver, P. A. (2011). Cell-to-cell variability of alternative RNA splicing. Molecular Systems Biology, 7(1), 506. https://doi.org/10.1038/msb.2011.32

Zambrano, S., Loffreda, A., Carelli, E., Stefanelli, G., Colombo, F., Bertrand, E., Tacchetti, C., Agresti, A., Bianchi, M. E., Molina, N., & Mazza, D. (2020). First Responders Shape a Prompt and Sharp NF-κB-Mediated Transcriptional Response to TNF-α. iScience, 23(9), 101529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101529