Peer review process

Revised: This Reviewed Preprint has been revised by the authors in response to the previous round of peer review; the eLife assessment and the public reviews have been updated where necessary by the editors and peer reviewers.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorDouglas PortmanUniversity of Rochester, Rochester, United States of America

- Senior EditorLu ChenStanford University, Stanford, United States of America

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

The authors investigated the role of the C. elegans Flower protein, FLWR-1, in synaptic transmission, vesicle recycling, and neuronal excitability. They confirmed that FLWR-1 localizes to synaptic vesicles and the plasma membrane and facilitates synaptic vesicle recycling at neuromuscular junctions. They observed that hyperstimulation results in endosome accumulation in flwr-1 mutant synapses, suggesting that FLWR-1 facilitates the breakdown of endocytic endosomes. Using tissue-specific rescue experiments, the authors showed that expressing FLWR-1 in GABAergic neurons restored the aldicarb-resistant phenotype of flwr-1 mutants to wild-type levels. By contrast, cholinergic neuron expression did not rescue aldicarb sensitivity at all. They also showed that FLWR-1 removal leads to increased Ca2+ signaling in motor neurons upon photo-stimulation. From these findings, the authors conclude that FLWR-1 helps maintain the balance between excitation and inhibition (E/I) by preferentially regulating GABAergic neuronal excitability in a cell-autonomous manner.

Overall, the work presents solid data and interesting findings, however the proposed cell-autonomous model of GABAergic FLWR-1 function may be overly simplified in my opinion.

Most of my previous comments have been addressed; however, two issues remain.

(1) I appreciate the authors' efforts conducting additional aldicarb sensitivity assays that combine muscle-specific rescue with either cholinergic or GABergic neuron-specific expression of FLWR-1. In the revised manuscript, they conclude, "This did not show any additive effects to the pure neuronal rescues, thus FLWR-1 effects on muscle cell responses to cholinergic agonists must be cell-autonomous." However, I find this interpretation confusing for the reasons outlined below.

Figure 1 - Figure Supplement 3B shows that muscle-specific FLWR-1 expression in flwr-1 mutants significantly restores aldicarb sensitivity. However, when FLWR-1 is co-expressed in both cholinergic neurons and muscle, the worms behave like flwr-1 mutants and no rescue is observed. Similarly, cholinergic FLWR-1 alone fails to restore aldicarb sensitivity (shown in the previous manuscript). These observations indicate a non-cell-autonomous interaction between cholinergic neurons and muscle, rather than a strictly muscle cell-autonomous mechanism. In other words, FLWR-1 expressed in cholinergic neurons appears to negate or block the rescue effect of muscle-expressed FLWR-1. Therefore, FLWR-1 could play a more complex role in coordinating physiology across different tissues. This complexity may affect interpretations of Ca2+ dynamics and/or functional data, particularly in relation to E/I balance, and thus warrants careful discussion or further investigation.

[Editor's note: The authors edited the text of the manuscript to acknowledge potential complexities in the interpretations of these results.]

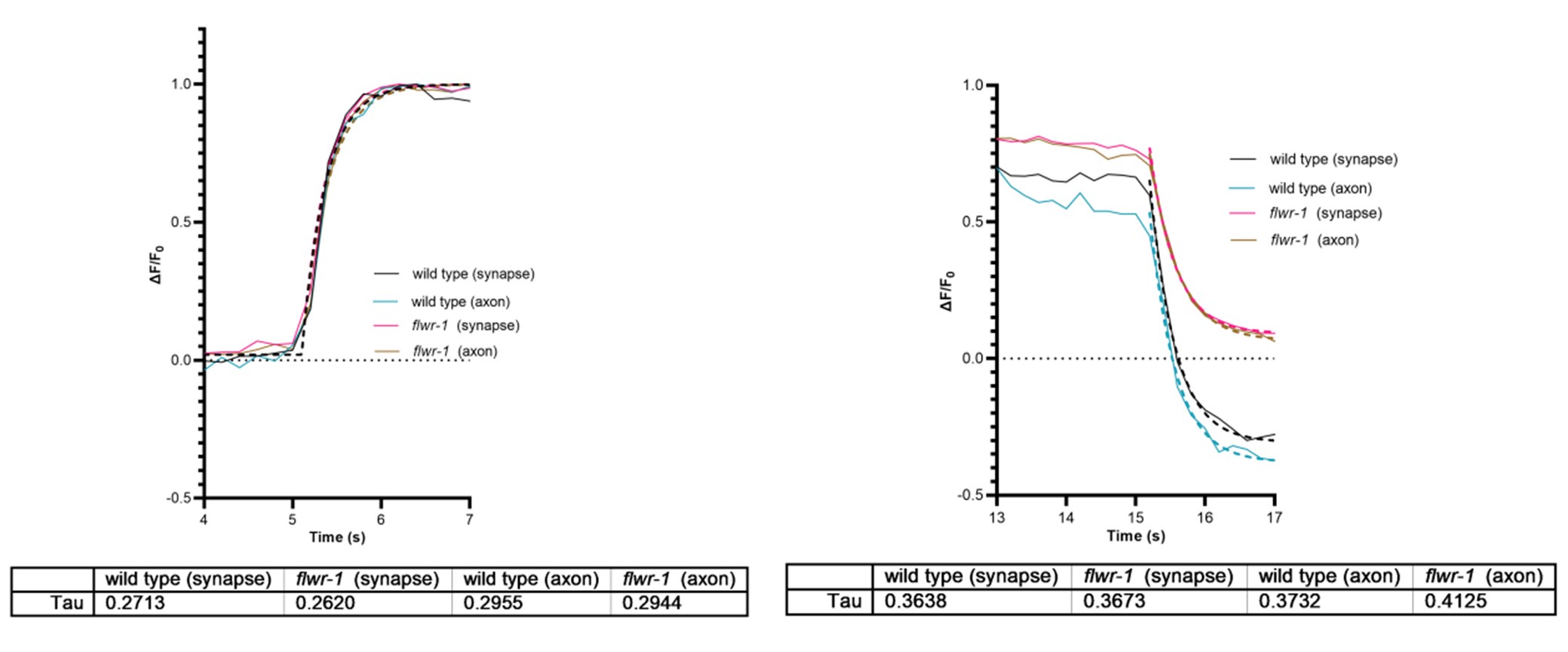

(2) The revised manuscript includes new GCaMP analyses restricted to synaptic puncta. The authors mention that "we compared Ca2+ signals in synaptic puncta versus axon shafts, and did not find any differences," concluding that "FLWR-1's impact is local, in synaptic boutons." This is puzzling: the similarity of Ca2+ signals in synaptic regions and axon shafts seems to indicate a more global effect on Ca2+ dynamics or may simply reflect limited temporal resolution in distinguishing local from global signals due to rapid Ca2+ diffusion. The authors should clarify how they reached the conclusion that FLWR-1 has a localized impact at synaptic boutons, given that synaptic and axonal signals appear similar. Based on the presented data, the evidence supporting a local effect of FLWR-1 on Ca2+ dynamics appears limited.

[Editor's note: The authors acknowledged that some wording in the previous version was misleading and inaccurate. In the revised version, the authors have withdrawn the conclusion that FLWR-1 function is local in synaptic boutons.]

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The Flower protein is expressed in various cell types, including neurons. Previous studies in flies have proposed that Flower plays a role in neuronal endocytosis by functioning as a Ca2+ channel. However, its precise physiological roles and molecular mechanisms in neurons remain largely unclear. This study employs C. elegans as a model to explore the function and mechanism of FLWR-1, the C. elegans homolog of Flower. This study offers intriguing observations that could potentially challenge or expand our current understanding of the Flower protein. Nevertheless, further clarification or additional experiments are required to substantiate the study's conclusions.

Strengths:

A range of approaches was employed, including the use of a flwr-1 knockout strain, assessment of cholinergic synaptic activity via analyzing aldicarb (a cholinesterase inhibitor) sensitivity, imaging Ca2+ dynamics with GCaMP3, analyzing pHluorin fluorescence, examination of presynaptic ultrastructure by EM, and recording postsynaptic currents at the neuromuscular junction. The findings include notable observations on the effects of flwr-1 knockout, such as increased Ca2+ levels in motor neurons, changes in endosome numbers in motor neurons, altered aldicarb sensitivity, and potential involvement of a Ca2+-ATPase and PIP2 binding in FLWR-1's function.

The authors have adequately addressed most of my previous concerns, however, I recommend minor revisions to further strengthen the study's rigor and interpretation:

Major suggestions

(1) This study relies heavily on aldicarb assays to support its conclusions. While these assays are valuable, their results may not fully align with direct assessment of neurotransmitter release from motor neurons. For instance, prior work has shown that two presynaptic modulators identified through aldicarb sensitivity assays exhibited no corresponding electrophysiological defects at the neuromuscular junction (Liu et al., J Neurosci 27: 10404-10413, 2007). Similarly, at least one study from the Kaplan lab has noted discrepancies between aldicarb assays and electrophysiological analyses. The authors should consider adding a few sentences in the Discussion to acknowledge this limitation and the potential caveats of using aldicarb assays, especially since some of the aldicarb assay results in this study are not easily interpretable.

[Editor's note: The authors added a sentence in the first paragraph of the Discussion to acknowledge these complexities.]

(2) The manuscript states, "Elevated Ca2+ levels were not further enhanced in a flwr-1;mca-3 double mutant." (lines 549-550). However, Figure 7C does not include statistical comparisons between the single and double mutants of flwr-1 and mca-3. Please add the necessary statistical analysis to support this statement.

[Editor's note: In response, the authors noted that these comparisons were indeed carried out. As mentioned in the figure legend, the graph shows only those comparisons that indicated statistical significance.]

(3) The term "Ca2+ influx" should be avoided, as this study does not provide direct evidence (e.g. voltage-clamp recordings of Ca2+ inward currents in motor neurons) for an effect of the flwr-1 mutation of Ca2+ influx. The observed increase in neuronal GCaMP signals in response to optogenetic activation of ChR2 may result from, or be influenced by, Ca2+ mobilization from of intracellular stores. For example, optogenetic stimulation could trigger ryanodine receptor-mediated Ca2+ release from the ER via calcium-induced calcium release (CICR) or depolarization-induced calcium release (DICR). It would be more appropriate to describe the observed increase in Ca2+ signal as "Ca2+ elevation" rather than increased "Ca2+ influx".

[Editor's note: The authors revised their terminology to avoid ambiguities associated with the word "influx".]