Peer review process

Revised: This Reviewed Preprint has been revised by the authors in response to the previous round of peer review; the eLife assessment and the public reviews have been updated where necessary by the editors and peer reviewers.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorChristian BüchelUniversity Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany

- Senior EditorChristian BüchelUniversity Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

Measurement of BOLD MR imaging has regularly found regions of the brain that show reliable suppression of BOLD responses during specific experimental testing conditions. These observations are to some degree unexplained, in comparison with more usual association between activation of the BOLD response and excitatory activation of the neurons (most tightly linked to synaptic activity) in the same brain location. This paper finds two patients whose brains were tested with both non-invasive functional MRI and with invasive insertion of electrodes, which allowed the direct recording of neuronal activity. The electrode insertions were made within the fusiform gyrus, which is known to process information abouit faces, in a clinical search for the sites of intractable epilepsy in each patient. The simple observation is that the electrode location in one patient showed activation of the BOLD response and activation of neuronal firing in response to face stimuli. This is the classical association. The other patient showed an informative and different pattern of responses. In this person, the electrode location showed a suppression of the BOLD response to face stimuli and, most interestingly, an associated suppression of neuronal activity at the electrode site.

Strengths:

Whilst these results are not by themselves definitive, they add an important piece of evidence to a long-standing discussion about the origins of the BOLD response. The observation of decreased neuronal activation associated with negative BOLD is interesting because, at various times, exactly the opposite association has been predicted. It has been previously argued that if synaptic mechanisms of neuronal inhibition are responsible for the suppression of neuronal firing, then it would be reasonable

Weaknesses:

The chief weakness of the paper is that the results may be unique in a slightly awkward way. The observation of positive BOLD and neuronal activation is made at one brain site in one patient, while the complementary observation of negative BOLD and neuronal suppression actually derives from the other patient. Showing both effects in both patients would make a much stronger paper.

Comments on revisions:

The material on lines 165-175 should not be left hidden away in the Methods section. This should be highlighted in the Discussion as a limitation of the current study and an issue that could be improved upon in future studies.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

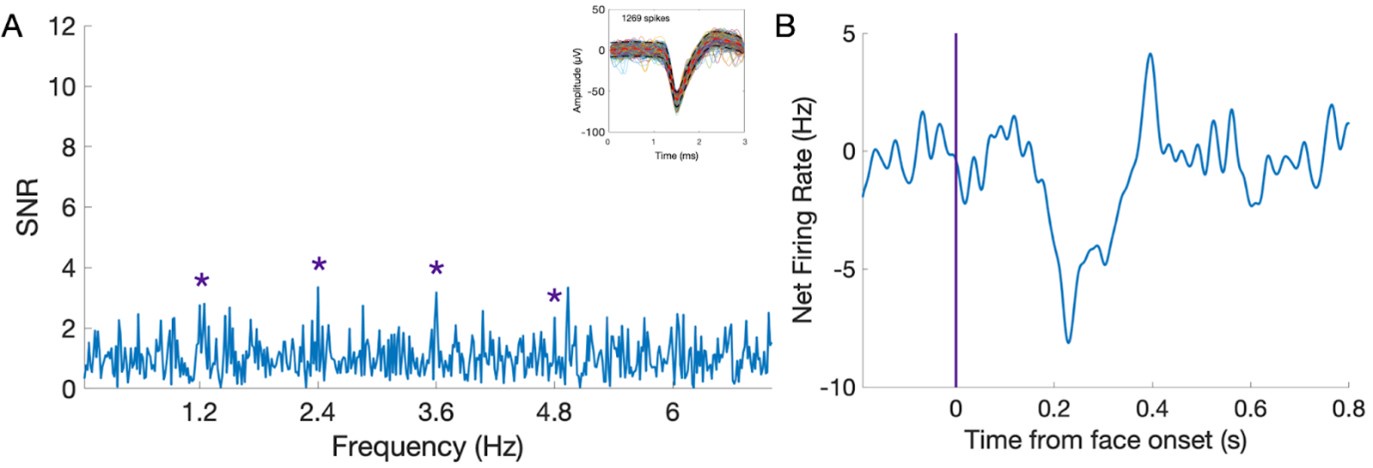

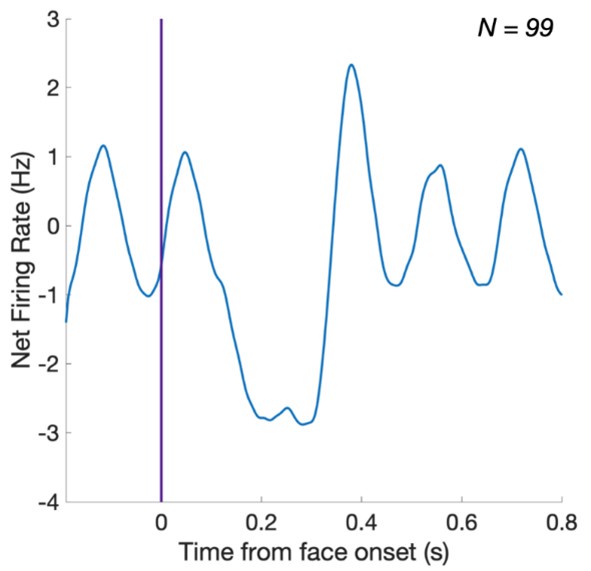

This is a short and straightforward paper describing BOLD fMRI and depth electrode measurements from two regions of the fusiform gyrus that show either higher or lower BOLD responses to faces vs. objects (which I will call face-positive and face-negative regions). In these regions, which were studied separately in two patients undergoing epilepsy surgery, spiking activity increased for faces relative to objects in the face-positive region and decreased for faces relative to objects in the face-negative region. Interestingly, about 30% of neurons in the face-negative region did not respond to objects and decreased their responses below baseline in response to faces (absolute suppression).

Strengths:

These patient data are valuable, with many recording sessions and neurons from human face-selective regions, and the methods used for comparing face and object responses in both fMRI and electrode recordings were robust and well-established. The finding of absolute suppression could clarify the nature of face selectivity in human fusiform gyrus, since previous fMRI studies of the face-negative region could not distinguish whether face < object responses came from absolute suppression, or just relatively lower but still positive responses to faces vs. objects.

Weaknesses:

The authors claim that the results tell us about both 1) face-selectivity in the fusiform gyrus, and 2) the physiological basis of the BOLD signal. However, I would like to see more of the data that supports the first claim included in the paper.

The authors report that ~30% of neurons showed absolute suppression, but those data are not shown separately from the neurons that only show relative reductions. It is difficult to evaluate the absolute suppression claim from the short assertion in the text alone (lines 105-106), although this is a critical claim in the paper.

Comments on revisions:

The authors have provided a figure showing one example neuron that shows absolute suppression in their response to reviewers; I would recommend including a similar panel in one of the paper figures showing data averaged across all neurons classified as showing absolute suppression.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

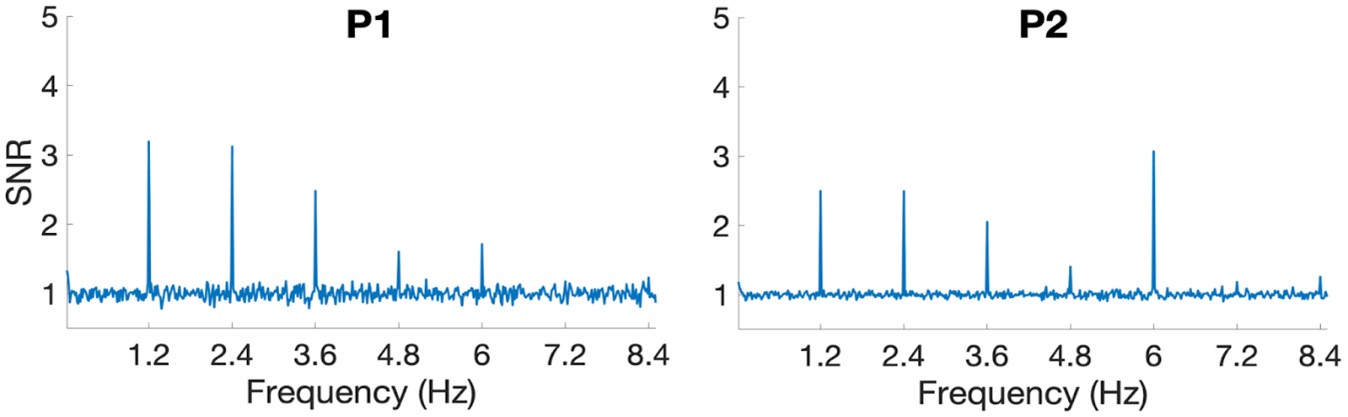

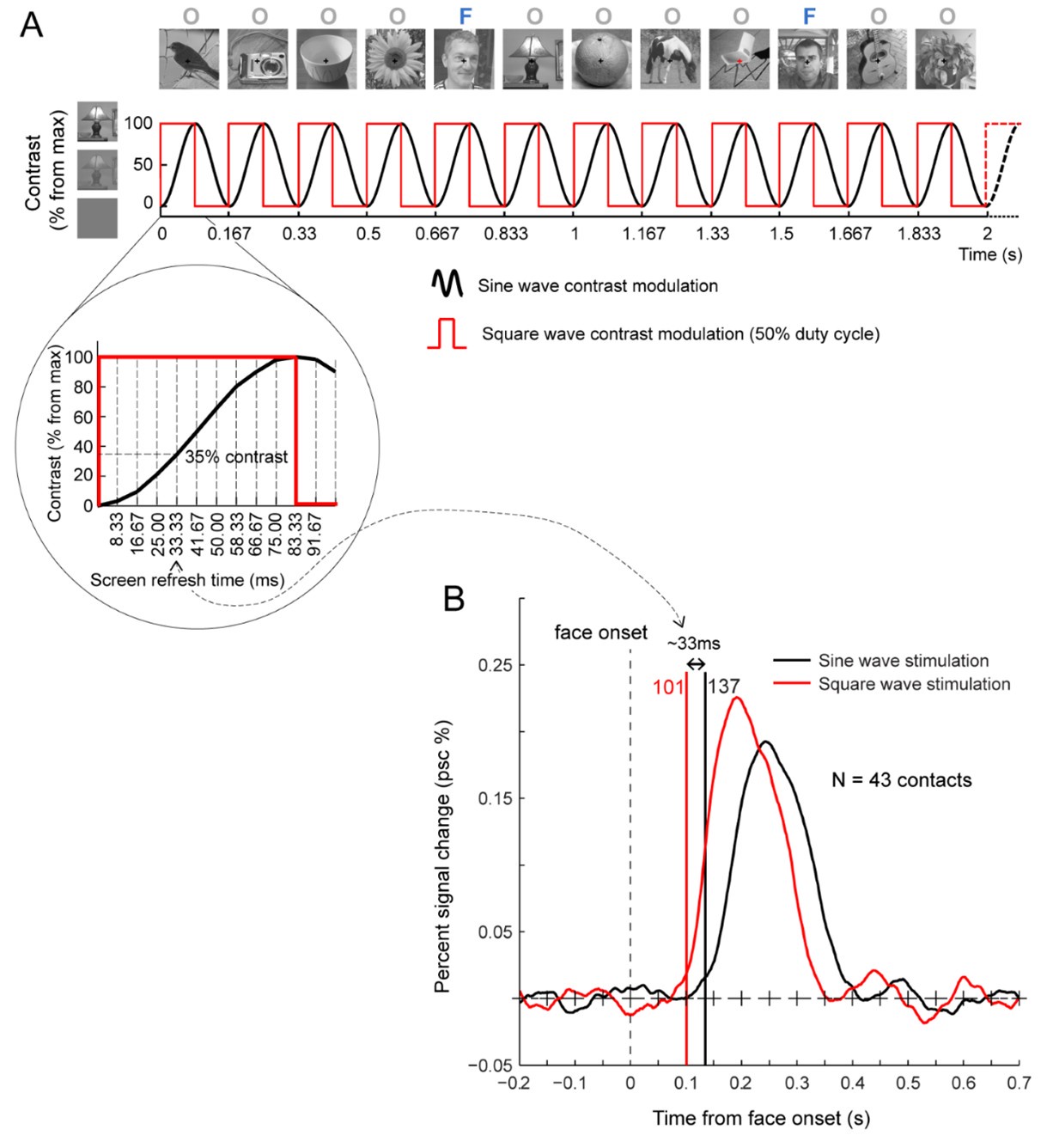

In this paper the authors conduct two experiments an fMRI experiment and intracranial recordings of neurons in two patients P1 and P2. In both experiments, they employ a SSVEP paradigm in which they show images at a fast rate (e.g. 6Hz) and then they show face images at a slower rate (e.g. 1.2Hz), where the rest of the images are a variety of object images. In the first patient, they record from neurons over a region in the mid fusiform gyrus that is face-selective and in the second patient, they record neurons from a region more medially that is not face selective (it responds more strongly to objects than faces). Results find similar selectivity between the electrophysiology data and the fMRI data in that the location which shows higher fMRI to faces also finds face-selective neurons and the location which finds preference to non faces also shows non face preferring neurons.

Strengths:

The data is important in that it shows that there is a relationship between category selectivity measured from electrophysiology data and category-selective from fMRI. The data is unique as it contains a lot of single and multiunit recordings (245 units) from the human fusiform gyrus - which the authors point out - is a humanoid specific gyrus.

Weaknesses:

My major concerns are two-fold: (i) There is a paucity of data; Thus, more information (results and methods) is warranted; and in particular there is no comparison between the fMRI data and the SEEG data.

(ii) One main claim of the paper is that there is evidence for suppressed responses to faces in the non-face selective region. That is, the reduction in activation to faces in the non-face selective region is interpreted as a suppression in the neural response and consequently the reduction in fMRI signal is interpreted as suppression. However, the SSVEP paradigm has no baseline (it alternates between faces and objects) and therefore it cannot distinguish between lower firing rate to faces vs suppression of response to faces.

(1) Additional data: the paper has 2 figures: figure 1 which shows the experimental design and figure 2 which presents data, the latter shows one example neuron raster plot from each patient and group average neural data from each patient. In this reader's opinion this is insufficient data to support the conclusions of the paper. The paper will be more impactful if the researchers would report the data more comprehensively.

(a) There is no direct comparison between the fMRI data and the SEEG data, except for a comparison of the location of the electrodes relative to the statistical parametric map generated from a contrast (Fig 2a,d). It will be helpful to build a model linking between the neural responses to the voxel response in the same location - i.e., estimate from the electrophysiology data the fMRI data (e.g. Logothetis & Wandell, 2004)

(b) More comprehensive analyses of the SSVEP neural data: It will be helpful to show the results of the frequency analyses of the SSVEP data for all neurons to show that there are significant visual responses and significant face responses. It will be also useful to compare and quantify the magnitude of the face responses compared to the visual responses.

(c) The neuron shown in E shows cyclical responses tied to the onset of the stimuli, is this the visual response? If so, why is there an increase in the firing rate of the neuron before the face stimulus is shown in time 0? The neuron's data seems different than the average response across neurons; This raises a concern about interpreting the average response across neurons in panel F which seems different than the single neuron responses

(d) Related to (c) it would be useful to show raster plots of all neurons and quantify if the neural responses within a region are homogeneous or heterogeneous. This would add data relating the single neuron response to the population responses measured from fMRI. See also Nir 2009.

(e) When reporting group average data (e.g., Fig 2C,F) it is necessary to show standard deviation of the response across neurons.

(f) Is it possible to estimate the latency of the neural responses to face and object images from the phase data? If so, this will add important information on the timing of neural responses in the human fusiform gyrus to face and object images.

(g) Related to (e) In total the authors recorded data from 245 units (some single units and some multiunits) and they found that both in the face and nonface selective most of the recoded neurons exhibited face -selectivity, which this reader found confusing: They write " Among all visually responsive neurons, we 87 found a very high proportion of face-selective neurons (p < 0.05) in both activated 88 and deactivated MidFG regions (P1: 98.1%; N = 51/52; P2: 86.6%; N = 110/127)'. Is the face selectivity in P1 an increase in response to faces and P2 a reduction in response to faces or in both it's an increase in response to faces

(1) Additional methods (a) it is unclear if the SSVEP analyses of neural responses were done on the spikes or the raw electrical signal. If the former, how is the SSVEP frequency analysis done on discrete data like action potentials? (b) it is unclear why the onset time was shifted by 33ms; one can measure the phase of the response relative to the cycle onset and use that to estimate the delay between the onset of a stimulus and the onset of the response. Adding phase information will be useful.

(2) Interpretation of suppression:

The SSVEP paradigm alternates between 2 conditions: faces and objects and has no baseline; In other words, responses to faces are measured relative to the baseline response to objects so that any region that contains neurons that have a lower firing rate to faces than objects is bound to show a lower response in the SSVEP signal. Therefore, because the experiment does not have a true baseline (e.g. blank screen, with no visual stimulation) this experimental design cannot distinguish between lower firing rate to faces vs suppression of response to faces. The strongest evidence put forward for suppression is the response of non-visual neurons that was also reduced when patients looked at faces, but since these are non-visual neurons, it is unclear how to interpret the responses to faces.

Comments on revisions:

In the revision, the authors added information and answered several of the main questions. Several points remain unanswered because the authors would like to publish a short format paper here, and suggest that answering these questions is outside the scope of the paper. The authors would like to leave some of the more detailed analyses for a subsequent longer paper.