Peer review process

Not revised: This Reviewed Preprint includes the authors’ original preprint (without revision), an eLife assessment, public reviews, and a provisional response from the authors.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorRichard NeherUniversity of Basel, Basel, Switzerland

- Senior EditorJoshua SchifferFred Hutch Cancer Center, Seattle, United States of America

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

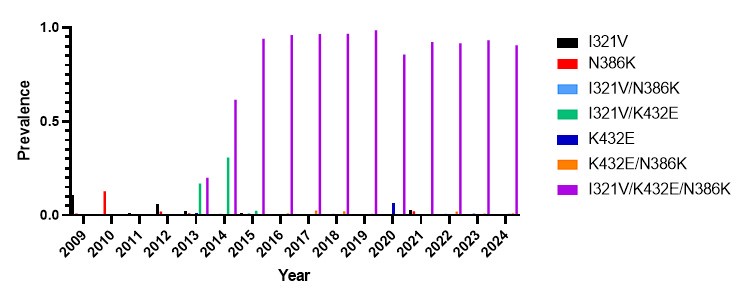

In this paper, the authors have performed an antigenic assay for human seasonal N1 neuraminidase using antigens and mouse sera from 2009-2020 (with one avian N1 antigen). This shows two distinct antigen groups. There is poorer reactivity with sera from 2009-2012 against antigens from 2015-2019, and poorer reactivity with sera from 2015-2020 against antigens from 2009-2013. There is a long branch separating these two groups. However, 321 and 423 are the only two positions that are consistently different between the two groups. Therefore these are the most likely cause of these antigenic differences.

Strengths:

(1) A sensible rationale was given for the choice of sera, in terms of the genetic diversity.

(2) There were two independent batches of one of the antigens used for generating sera, which demonstrated the level of heterogeneity in the experimental process.

(3) Replicate of the Wisconsin/588/2019 antigen (as H1 and H6) is another useful measure of heterogeneity.

(4) The presentation of the data, e.g. Figure 2, clearly shows two main antigenic groups.

(5) The most modern sera are more recent than other related papers, which demonstrates that has been no major antigenic change.

Weaknesses:

(1) Issues with experimental methods

As I am not an experimentalist, I cannot comment fully on the experimental methods. However, I note that BALB/c mice sera were used, whereas outbred ferret sera are typically used in influenza antigenic characterisation, so the antigenic difference observed may not be relevant in humans. Similarly, the mice were immunised with an artificial NA immunogen where the typical approach would be to infect the ferret with live virus intra-nasally.

(2) Five mice sera were generated per immunogen and then pooled, but data was not presented that demonstrated these sera were sufficiently homogenous that this approach is valid.

(3) There were no homologous antigens for most of the sera. This makes the responses difficult to interpret as the homologous titre is often used to assess the overall reactivity of a serum. The sequence of the antigens used is not described, which again makes it difficult to interpret the results.

(4) To be able to untangle the effects of the individual substitutions at 321, 386, and 432, it would have been useful to have included the naturally occurring variants at these positions, or to have generated mutants at these positions. Gao et al clearly show an antigenic difference with ferret sera correlated separately with N386K and I321V/K432E.

(5) The challenge experiments in Gao et al showed that NI titre was not a good correlate of protection, so that limits the interpretation of these results.

Issues with the computational methods

(6) The NAI titres were normalised using the ELISA results, and the motivation for this is not explained. It would be nice to see the raw values.

(7) It is not clear what value the random forest analysis adds here, given that positions 321 and 432 are the only two that consistently differ between the two groups.

(8) As with the previous N2 paper, the metric for antigenic distance (the root mean square of the difference between the titres for two sera) is not one that would be consistent when different sera are included. More usual metrics of distance are Archetti-Horsfall, fold down from homologous, or fold down from maximum.

(9) Antigenic cartography of these data is fraught. I wonder whether 2 dimensions are required for what seems like a 1-dimensional antigenic difference - certainly, the antigens, excluding the H5N1, are in a line. The map may be skewed by the high reactivity Brisbane/18 antigen. It is not clear if the column bases (normalisation factors for calculating antigenic distance) have been adjusted to account for the lack of homologous antigens. It is typical to present antigenic maps with a 1:1 x:y ratio.

Issues with interpretation

(10) Figure 2 shows the NAI titres split into two groups for the antigens, however, A/Brisbane is an outlier in the second antigenic group with high reactivity.

(11) Following Gao et al, I think you can claim that it is more likely that the antigenic change is due to K432E than I321V, based on a comparison of the amino acid change.

Appraisal:

Taking into account the limitations of the experimental techniques (which I appreciate are due to resource constraints), this paper meets its aim of measuring the antigenic relationships between 2009-2020 seasonal N1s, showing that there were two main groups. The authors discovered that the difference between the two antigenic groups was likely attributable to positions 321 and 432, as these were the only two positions that were consistently different between the two groups. They came to this finding by using a random forest model, but other simpler methods could have been used.

Impact:

This paper contributes to the growing literature on the potential benefit of NA in the influenza vaccine.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

In this study, Catani et al. have immunized mice with 17 recombinant N1 neuraminidases (NAs) from human isolates circulating between 2009-2020 to investigate antigenic diversity. NA inhibition (NAI) titers revealed two groups that were antigenically and phylogenetically distinct. Machine learning was used to estimate the antigenic distances between the N1 NAs and mutations at residues K432E and I321V were identified as key determinants of N1 NA antigenicity.

Strengths:

Observation of mutations associated with N1 antigenic drift.

Weaknesses:

Validation that K432E and I321V are responsible for antigenic drift was not determined in a background strain with native K432 and I321 or the restitution of antibody binding by reversion to K432 and I321 in strains that evaded sera.