Peer review process

Not revised: This Reviewed Preprint includes the authors’ original preprint (without revision), an eLife assessment, public reviews, and a provisional response from the authors.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorHarini IyerHoward Hughes Medical Institute, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, United States of America

- Senior EditorDidier StainierMax Planck Institute for Heart and Lung Research, Bad Nauheim, Germany

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

The article entitled "Pu.1/Spi1 dosage controls the turnover and maintenance of microglia in zebrafish and mammals" by Wu et al., identifies a role for the master myeloid developmental regulator Pu.1 in the maintenance of microglial populations in the adult. Using a non-homologous end joining knock-in strategy, the authors generated a pu.1 conditional allele in zebrafish, which reports wildtype expression of pu.1 with EGFP and truncated expression of pu.1 with DsRed after Cre-mediated recombination. When crossed to existing pu.1 and spi-b mutants, this approach allowed the authors to target a single allele for recombination and induce homozygous loss-of-function microglia in adults. This identified that although there is no short-term consequence to loss of pu.1, microglia lacking any functional copy of pu.1 are depleted over the course of months, even when spi-b is fully functional. The authors go on to identify reduced proliferation, increased cell death, and higher expression of tp53 in the pu.1 deficient microglia, as compared to the wild-type EGFP+ microglia. To extend these findings to mammals, the authors generated a conditional Pu.1 allele in mice and performed similar analyses, finding that loss of a single copy of Pu.1 resulted in similar long-term loss of Pu.1-deficient microglia. The conclusions of this paper are overall well supported by the data.

Strengths:

The genetic approaches here for visualizing the recombination status of an endogenous allele are very clever, and by comparing the turnover of wildtype and mutant cells in the same animal the authors can make very convincing arguments about the effect of chronic loss of pu.1. Likely this phenotype would be either very subtle or nonexistent without the point of comparison and competition with the wildtype cells.

Using multiple species allows for more generalizable results, and shows conservation of the phenomena at play.

The demonstration of changes to proliferation and cell death in concert with higher expression of tp53 is compelling evidence for the authors' argument.

Weaknesses:

This paper is very strong. It would benefit from further investigating the specific relationship between pu.1 and tp53 specifically. Does pu.1 interact with the tp53 locus? Specific molecular analysis of this interaction would strengthen the mechanistic findings.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

In the presented work by Wu et al, the authors investigate the role of the transcription factor Pu.1 in the survival and maintenance of microglia, the tissue-resident macrophage population in the brain. To this end, they generated a sophisticated new conditional pu.1 allele in zebrafish using CRISPR-mediated genome editing which allows visual detection of expression of the mutant allele through a switch from GFP to dsRed after Cre-mediated recombination. Using EdU pulse-chase labelling, they first estimated the daily turnover rate of microglia in the adult zebrafish brain which was found to be higher than rates previously estimated for mice and humans. After conditional deletion of pu.1 in coro1a positive cells, they do not find a difference in microglia number at 2 and 8 days or 1-month post-injection of Tamoxifen. However, at 3 months post-injection, a strong decrease in mutant microglia could be detected. While no change in microglia number was detected at 1mpi, an increase in apoptotic cells and decreased proliferation as observed. RNA-seq analysis of WT and mutant microglia revealed an upregulation of tp53, which was shown to play a role in the depletion of pu.1 mutant microglia as deletion in tp53-/- mutants did not lead to a decrease in microglia number at 3mpi. Through analysis of microglia number in pU.1 mutants, the authors further show that the depletion of microglia in the conditional mutants is dependent on the presence of WT microglia. To show that the phenomenon is conserved between species, similar experiments were also performed in mice.

This work expands on previous in vitro studies using primary human microglia. The majority of conclusions are well supported by the data, addition of controls and experimental details would strengthen the conclusions and rigor of the paper.

Strengths:

Generation of an elegantly designed conditional pu.1 allele in zebrafish that allows for the visual detection of expression of the knockout allele.

The combination of analysis of pu.1 function in two model systems, zebrafish and mouse, strengthens the conclusions of the paper.

Confirmation of the functional significance of the observed upregulation of tp53 in mutant microglia through double mutant analysis provides some mechanistic insight.

Weaknesses:

(1) The presented RNA-Seq analysis of mutant microglia is underpowered and details on how the data was analyzed are missing. Only 9-15 cells were analyzed in total (3 pools of 3-5 cells each). Further, the variability in relative gene expression of ccl35b.1, which was used as a quality control and inclusion criterion to define pools consisting of microglia, is extremely high (between ~4 and ~1600, Figure S7A).

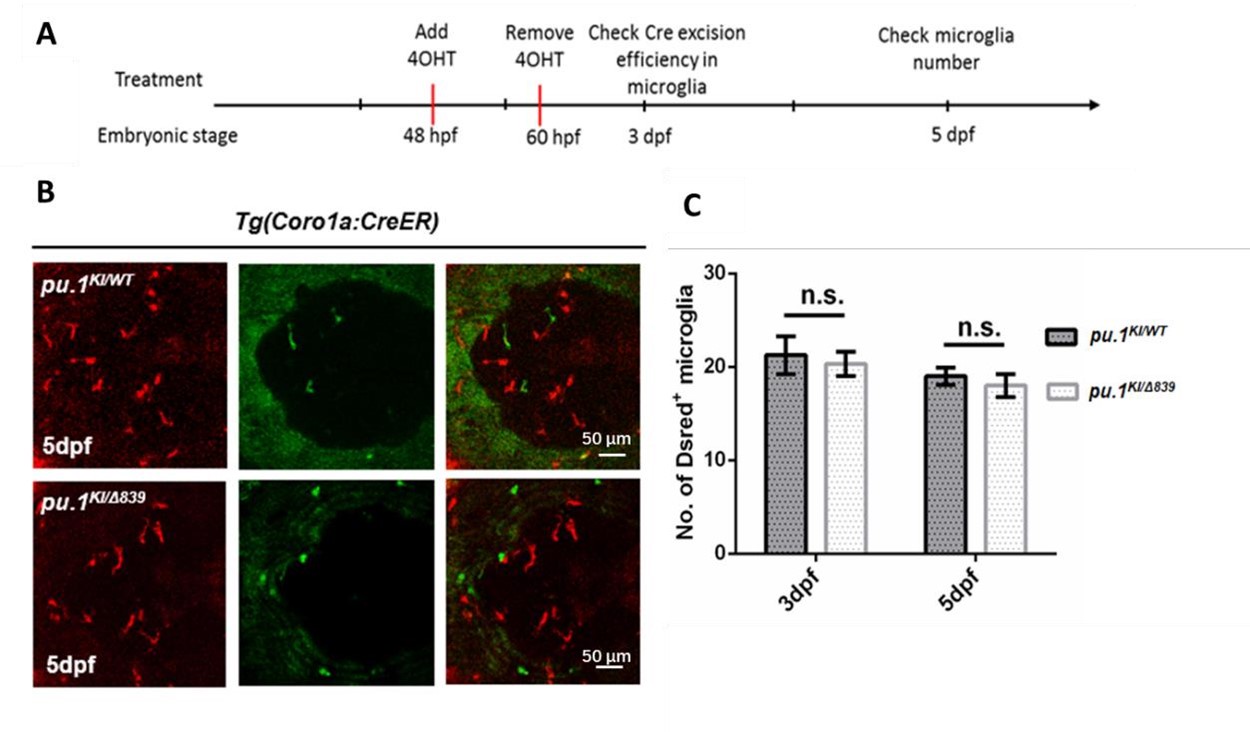

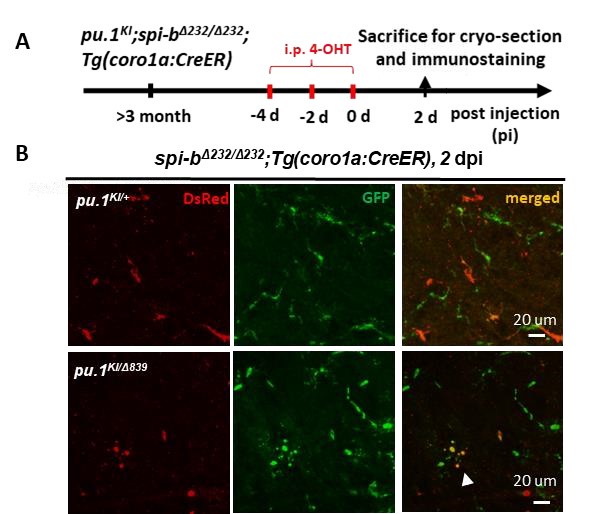

(2) The authors conclude that the reduction of microglia observed in the adult brain after cKO of pu.1 in the spi-b mutant background is due to apoptosis (Lines 213-215). However, they only provide evidence of apoptosis in 3-5 dpf embryos, a stage at which loss of pu.1 alone does lead to a complete loss of microglia (Figure 2E). A control of pu.1 KI/d839 mutants treated with 4-OHT should be added to show that this effect is indeed dependent on the loss of spi-b. In addition, experiments should be performed to show apoptosis in the adult brain after cKO of pu.1 in spi-b mutants as there seems to be a difference in the requirement of pu.1 in embryonic and adult stages.

(3) The number of microglia after pu.1 knockout in zebrafish did only show a significant decrease 3 months after 4-OHT injection, whereas microglia were almost completely depleted already 7 days after injection in mice. This major difference is not discussed in the paper.

(4) Data is represented as mean +/-.SEM. Instead of SEM, standard deviation should be shown in all graphs to show the variability of the data. This is especially important for all graphs where individual data points are not shown. It should also be stated in the figure legend if SEM or SD is shown.