Peer review process

Revised: This Reviewed Preprint has been revised by the authors in response to the previous round of peer review; the eLife assessment and the public reviews have been updated where necessary by the editors and peer reviewers.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorXing TianNew York University Shanghai, Shanghai, China

- Senior EditorHuan LuoPeking University, Beijing, China

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

In this fMRI study, the authors wished to assess neural mechanisms supporting flexible temporal construals. For this, human participants learned a story consisting of fifteen events. During fMRI, events were shown to them, and participants were instructed to consider the event from "an internal" or from "an external" perspective. The authors found distinct patterns of brain activity in the posterior parietal cortex (PPC) and anterior hippocampus for the internal and the external viewpoint. Specifically, activation in the posterior parietal cortex positively correlated with distance during the external-perspective task, but negatively during the internal-perspective task. The anterior hippocampus positively correlated with distance in both perspectives. The authors conclude that allocentric sequences are stored in the hippocampus, whereas egocentric sequences are supported by the parietal cortex.

Strengths:

The research topic is fascinating, and very few labs in the world are asking the question of how time is represented in the human brain. Working hypotheses have been recently formulated, and the work tackles them from the perspective of construals theory.

Weaknesses:

Although the work uses two distinct psychological tasks, the authors do not elaborate on the cognitive operationalization the tasks entail, nor the implication of the task design for the observed neural activation.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

Xu et al. used fMRI to examine the neural correlates associated with retrieving temporal information from an external compared to internal perspective ('mental time watching' vs. 'mental time travel'). Participants first learned a fictional religious ritual composed of 15 sequential events of varying durations. They were then scanned while they either (1) judged whether a target event happened in the same part of the day as a reference event (external condition); or (2) imagined themselves carrying out the reference event and judged whether the target event occurred in the past or will occur in the future (internal condition). Behavioural data suggested that the perspective manipulation was successful: RT was positively correlated with sequential distance in the external perspective task, while a negative correlation was observed between RT and sequential distance for the internal perspective task. Neurally, the two tasks activated different regions, with the external task associated with greater activity in the supplementary motor area and supramarginal gyrus, and the internal condition with greater activity in default mode network regions. Of particular interest, only a cluster in the posterior parietal cortex demonstrated a significant interaction between perspective and sequential distance, with increased activity in this region for longer sequential distances in the external task but increased activity for shorter sequential distances in the internal task. Only a main effect of sequential distance was observed in the hippocampus head, with activity being positively correlated with sequential distance in both tasks. No regions exhibited a significant interaction between perspective and duration, although there was a main effect of duration in the hippocampus body with greater activity for longer durations, which appeared to be driven by the internal perspective condition. On the basis of these findings, the authors suggest that the hippocampus may represent event sequences allocentrically, whereas the posterior parietal cortex may process event sequences egocentrically.

Strengths:

The topic of egocentric vs. allocentric processing has been relatively under-investigated with respect to time, having traditionally been studied in the domain of space. As such, the current study is timely and has the potential to be important for our understanding of how time is represented in the brain in the service of memory. The study is well thought out and the behavioural paradigm is, in my opinion, a creative approach to tackling the authors' research question. A particular strength is the implementation of an imagination phase for the participants while learning the fictional religious ritual. This moves the paradigm beyond semantic/schema learning and is probably the best approach besides asking the participants to arduously enact and learn the different events with their exact timings in person. Importantly, the behavioural data point towards successful manipulation of internal vs. external perspective in participants, which is critical for the interpretation of the fMRI data. The use of syllable length as a sanity check for RT analyses as well as neuroimaging analyses is also much appreciated.

Suggestions:

The authors have done a commendable job addressing my previous comments. In particular, the additional analyses elucidating the potential contribution of boundary effects to the behavioural data, the impact of incorporating RT into the fMRI GLMs, and the differential contributions of RT and sequential distance to neural activity (i.e., in PPC) are valuable and strengthen the authors' interpretation of their findings.

My one remaining suggestion pertains to the potential contribution of boundary effects. While the new analyses suggest that the RT findings are driven by sequential distance and duration independent of a boundary effect (i.e., Same vs. Different factor), I'm wondering whether the same applies to the neural findings? In other words, have the authors run a GLM in which the Same vs. Different factor is incorporated alongside distance and duration?

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

In this fMRI study, the authors wished to assess neural mechanisms supporting flexible "temporal construals". For this, human participants learned a story consisting of fifteen events. During fMRI, events were shown to them, and they were instructed to consider the event from "an internal" or from "an external" perspective. The authors found opposite patterns of brain activity in the posterior parietal cortex and the anterior hippocampus for the internal and the external viewpoint. They conclude that allocentric sequences are stored in the hippocampus, whereas egocentric sequences are used in the parietal cortex. The claims align with previous fMRI work addressing this question.

We appreciate the reviewer's concise summary of our research. We would like to offer two clarifications to prevent any potential misunderstandings.

First, the activity patterns in the parietal cortex and hippocampus are not entirely opposite across internal and external perspectives. Specifically, the activation level in the posterior parietal cortex shows a positive correlation with sequential distance during external-perspective tasks, but a negative correlation during internal-perspective tasks. In contrast, the activation level in the anterior hippocampus positively correlates with sequential distance, irrespective of the observer's perspective. Therefore, our results suggest that the parietal cortex, with its perspective-dependent activity, supports egocentric representation; the hippocampus, with its consistent activity across perspectives, supports allocentric representation.

Second, while some of our findings align with previous fMRI studies, to our knowledge, no prior research has explicitly investigated how the neural representation of time may vary depending on the observer's viewpoint. This gap in the literature is the primary motivation for our current study.

Strengths:

The research topic is fascinating, and very few labs in the world are asking the question of how time is represented in the human brain. Working hypotheses have been recently formulated, and this work seems to want to tackle some of them.

We appreciate the reviewer's acknowledgment of the theoretical significance of our study.

Weaknesses:

The current writing is fuzzy both conceptually and experimentally. I cannot provide a sufficiently well-informed assessment of the quality of the experimental work because there is a paucity of details provided in the report. Any future revisions will likely improve transparency.

(1) Improving writing and presentation:

The abstract and the introduction make use of loaded terms such as "construals", "mental timeline", "panoramic views" in very metaphoric and unexplained ways. The authors do not provide a comprehensive and scholarly overview of these terms, which results in verbiage and keywords/name-dropping without a clear general framework being presented. Some of these terms are not metaphors. They do refer to computational concepts that the authors should didactically explain to their readership. This is all the more important that some statements in the Introduction are misattributed or factually incorrect; some statements lack attributions (uncited published work). Once the theory, the question, and the working hypothesis are clarified, the authors should carefully explain the task.

We appreciate the reviewer's critics.

The formulation of the scientific question in the introduction is grounded in the spatial construals of time hypothesis and conceptual metaphor theory (e.g., Traugott, 1978; Lakoff & Johnson, 1980; see recent reviews by Núñez & Cooperrider, 2013; Bender & Beller, 2014). These frameworks were originally developed through analyses of how spatial metaphors are used to describe temporal concepts in natural language. Consequently, it is theoretically motivated and largely unavoidable to introduce the two primary temporal construals—mental time travel and mental time watching— using metaphorical expressions.

However, we do agree with the reviewer that the introduction in the original manuscript was overly long and that the working hypothesis was not clearly stated. In the revised manuscript, we have streamlined the introduction and substantially revised the following two paragraphs to clarify the formulation of our working hypothesis (Pages 5-6):

“Recent studies have already begun to investigate the neural representation of the memorized event sequence (e.g., Deuker et al., 2016; Thavabalasingam et al., 2018; Bellmund et al., 2019, 2022; see reviews by Cohn-Sheehy & Ranganath, 2017; Bellmund et al., 2020). Yet, the neural mechanisms that enable the brain to construct distinct construals of an event sequence remain largely unknown. Valuable insights may be drawn from research in the spatial domain, which diPerentiates the neural representation in allocentric and egocentric reference frames. According to an influential neurocomputational model (Byrne et al., 2007; Bicanski & Burgess, 2018; Bicanski & Burgess, 2020), allocentric and egocentric spatial representations are dissociable in the brain—they are respectively implemented in the medial temporal lobe (MTL)—including the hippocampus—and the parietal cortex. Various egocentric representations in the parietal cortex derived from diPerent viewpoints can be transformed and integrated into a unified allocentric representation and stored in the MTL (i.e., bottom-up process). Conversely, the allocentric representation in the MTL can serve as a template for reconstructing diverse egocentric representations across diPerent viewpoints in the parietal cortex (i.e., top-down process).”

“In line with the spatial construals of time hypothesis, several authors have recently suggested that such mutually engaged egocentric and allocentric reference frames (in the parietal cortex and the medial temporal lobe, respectively) proposed in the spatial domain might also apply to the temporal one (e.g., Gauthier & van Wassenhove, 2016ab; Gauthier et al., 2019, 2020; Bottini & Doeller, 2020). If this hypothesis holds, it could explain how the brain flexibly generates diverse construals of the same event sequence. Specifically, the hippocampus may encode a consistent representation of an event sequence that is independent of whether an individual adopts an internal or external perspective, reflecting an allocentric representation of time. In contrast, parietal cortical representations are expected to vary flexibly with the adopted perspective that is shaped by task demands, reflecting an egocentric representation of time.”

In the revised manuscript, we also corrected statements in the Introduction that may have been misattributed (see Reviewer 2, comment 4(ii)) and added several relevant and important publications.

(2) The experimental approach lacks sufficient details to be comprehensible to a general audience. In my opinion, the results are thus currently uninterpretable. I highlight only a couple of specific points (out of many). I recommend revision and clarification.

(a) No explanation of the narrative is being provided. The authors report a distribution of durations with no clear description of the actual sequence of events. The authors should provide the text that was used, how they controlled for low-level and high-level linguistic confounds.

We thank the reviewer for the suggestions. The event sequence for the odd-numbered participants is shown in the original Figure 1. In the revised manuscript, we added to Figure 1 the figure supplement 1 to illustrate the actual sequence of events for the participants with both odd and even numbers. We also added the narratives used in the reading phase of the learning procedures for the participants with both odd and even numbers (Figure 1—source data 1).

To control for low-level linguistic confounds, we included the number of syllables as a covariate in the first-level general linear model in the fMRI analysis. To address high-level linguistic confounds, such as semantic information (which is difficult to quantify), we randomly assigned event labels to the 15 events twice, creating two counterbalanced versions for participants with even and odd numbers (see Comment 2b below).

(b) The authors state, "we randomly assigned 15 phrases to the events twice". It is impossible to comprehend what this means. Were these considered stimuli? Controls? IT is also not clear which event or stimulus is part of the "learning set" and whether these were indicated to be such to participants.

We apologize for any confusion in the Results section and the legend of Figure 1. Our motivation was explained in the "Stimuli" section of the Methods. In the revised manuscript, we have clarified this by adding an explanation to the legend of Figure 1 and including the supplementary Figure 1: " To minimize potential confounds between the semantic content of the event phrases and the temporal structure of the events, we randomly assigned the phrases to the events, creating two versions for participants with even and odd ID numbers. Both versions can be seen in Figure1—figure supplement 1 and Figure 1—source data 1."

(c) The left/right counterbalancing is not being clearly explained. The authors state that there is counterbalancing, but do not sufficiently explain what it means concretely in the experiment. If a weak correlation exists between sequential position and distance, it also means that the position and the distance have not been equated within. How do the authors control for these?

We thank the reviewer for highlighting this point and apologize for the lack of clarity in the original manuscript. In the current version (Page 40), we have provided further clarification: “We carefully selected two sets of 20 event pairs from the 210 possible combinations, assigning them to the odd and even runs of the fMRI experiment. Using a brute-force search, we identified 20 pairs in which sequential distance showed only weak correlations with positional information for both reference and target events (ranging from 1 to 15), as well as with behavioral responses (Same vs. Different or Future vs. Past, coded as 0 and 1), with all correlation coefficients below 0.2. At the same time, we balanced the proportion of correct responses across conditions: for the external-perspective task, Same/Different = 11/9 and 12/8; for the internal-perspective task, Future/Past = 12/8 and 8/12. Under these constraints, the sequential distances in both sets ranged from 1 to 5. To further mitigate spatial response biases, we pseudorandomized the left/right on-screen positions of the two response options within each task block, while ensuring an equal number of correct responses mapped to the left and right buttons (i.e., 10 per block).”

The event pairs we selected already represent the best possible choice given all the criteria we aimed to satisfy. It is impossible to completely eliminate all potential correlations. For instance, if the target event occurs near the beginning of the day, it will tend to fall in the past, whereas if it occurs near the end of the day, it is more likely to fall in the future. To further ensure that the significant results were not driven by these weak confounding factors, we constructed another GLM that included three additional parametric modulators: the sequence position of the target event (ranging from 1 to 15) and the behavioral responses (Future vs. Past in the internal-perspective task; Same vs. Different in the external-perspective task, coded as 0 and 1). The significant findings were unaffected.

(d) The authors used two tasks. In the "external perspective" one, the authors asked participants to report whether events were part of the same or a different part of the day. In the "internal perspective one", the authors asked participants to project themselves to the reference event and to determine whether the target event occurred before or after the projected viewpoint. The first task is a same/different recognition task. The second task is a temporal order task (e.g., Arzy et al. 2009). These two asks are radically different and do not require the same operationalization. The authors should minimally provide a comprehensive comparison of task requirements, their operationalization, and, more importantly, assess the behavioral biases inherent to each of these tasks that may confound brain activity observed with fMRI.

We understand the reviewer’s concern. We agree that there is a substantial difference between the two tasks. However, the primary goal of this study was not to directly compare these tasks to isolate a specific cognitive component. Rather, the neural correlates of temporal distance were first identified as brain regions showing a significant correlation between neural activity and temporal distance using the parametric modulation analysis. We then compared these neural correlates between the two tasks. Therefore, any general differences between the tasks should not be a confound for our main results. Our aim was to examine whether the hippocampal representation of temporal distance remains consistent across different perspectives, and whether the parietal representation of temporal distance varies as a function of the perspective adopted.

Therefore, the main aim of our task manipulation was to ensure that participants adopted either an external or an internal perspective on the event sequence, depending on the task condition. In the Introduction (Pages 6–7), we clarify this manipulation as follows: “In the externalperspective task, participants localized events with respect to external temporal boundaries, judging whether the target event occurred in the same or a different part of the day as the reference event. In the internal-perspective task, participants were instructed to mentally project themselves into the reference event and localize the target event relative to their own temporal point, judging whether the target event happened in the future or the past of the reference event (see Methods for details of the scanning procedure).”

We believe this task manipulation was successful. Behaviorally, the two tasks showed opposite correlations between reaction time and temporal distance, resembling the symbolic distance versus mental scanning effect. Neurally, contrasting the internal- and external-perspective tasks revealed activation of the default mode network, which is known to play a central role in self-projection (Buckner et al., 2017).

(e) The authors systematically report interpreted results, not factual data. For instance, while not showing the results on behavioral outcomes, the authors directly interpret them as symbolic distance effects.

Thank you for this comment. In the original paper, we reported the relevant statistics before our interpretation: “Sequential Distance was correlated positively with RT in the external-perspective task (z = 3.80, p < 0.001) but negatively in the internal-perspective task (z = -3.71, p < 0.001).” However, they may have been difficult to notice, and we are including a figure for the RT analysis in the revised manuscript.

Crucially, the authors do not comment on the obvious differences in task difficulty in these two tasks, which demonstrates a substantial lack of control in the experimental design. The same/different task (task 1 called "external perspective") comes with known biases in psychophysics that are not present in the temporal order task (task 2 called " internal perspective"). The authors also did not discuss or try to match the performance level in these two tasks. Accordingly, the authors claim that participants had greater accuracy in the external (same/different) task than in the internal task, although no data are shown and provided to support this report. Further, the behavioral effect is trivialized by the report of a performance accuracy trade off that further illustrates that there is a difference in the task requirements, preventing accurate comparison of the two tasks.

As noted in Question 2d, we acknowledge the substantial difference between the two tasks. However, the primary goal of this study was not to directly compare these tasks to isolate a specific cognitive component. Instead, we first identified the neural correlates of temporal distance as brain regions showing a significant correlation between neural activity and temporal distance, independent of task demands. We then compared these neural correlates across the two task conditions, which were designed to engage different temporal perspectives. Therefore, any general differences between the tasks should not be a confound for our main findings and interpretation.

Our aim was to investigate whether the hippocampal representation of temporal distance remains consistent across different perspectives and whether the parietal representation of temporal distance varies as a function of the perspective adopted. We do not see how this doubledissociation pattern could be explained by differences in task difficulty.

While we do not consider the overall difference in task difficulty between the two tasks to be a confounding factor, we acknowledge the potential confound posed by variations in task difficulty across temporal distances (1 to 5). This concern arises from the similarity between the activity patterns in the posterior parietal cortex and reaction time across temporal distances. To address this, we conducted control analyses to test this hypothesis (see the second and third points from Reviewer 2 for details).

On page 8, we present the behavioral accuracy data: “Participants showed significantly higher accuracy in the external-perspective task than in the internal-perspective task (external-perspective task: M = 93.5%, SD = 4.7%; internal-perspective task: M = 89.5%, SD = 8.1%; paired t(31) = 3.33, p = 0.002).”

All fMRI contrasts are also confounded by this experimental shortcoming, seeing as they are all reported at the interaction level across a task. For instance, in Figure 4, the authors report a significant beta difference between internal and external tasks. It is impossible to disentangle whether this effect is simply due to task difference or to an actual processing of the duration that differs across tasks, or to the nature of the representation (the most difficult to tackle, and the one chosen by the authors).

We thank the reviewer for pointing out this important issue. Like temporal distance, the neural correlates of duration were not derived from a direct contrast between the two tasks. Instead, they were identified by detecting brain regions showing a significant correlation between neural activity and the implied duration of each event using the parametric modulation analysis. Therefore, what is shown in Figure 4 reflects the significant differences in these neural correlations with duration between the two tasks.

The observed difference in the neural representation of duration between the two tasks was unexpected. In the original manuscript, we provided a post hoc explanation: “Since the externalperspective task in the current study encouraged the participants to compare the event sequence with the external parallel temporal landmarks, duration representation in the hippocampus may be dampened.”

However, we agree that this difference might also arise from other factors distinguishing the two tasks. In the revised manuscript, we have clarified this possibility as follows: “The difference in duration representation between the two tasks remains open to interpretation. One possible explanation is that the hippocampus is preferentially involved in memory for durations embedded within event sequences (see review by Lee et al., 2020). In the internal-perspective task, participants indeed localized events within the event sequence itself. In contrast, the externalperspective task encouraged participants to compare the event sequence with external temporal landmarks, which may have attenuated the hippocampal representation of duration.”

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the current experimental work is confounded and lacks controls. Any behavioral or fMRI contrasts between the two proposed tasks can be parsimoniously accounted for by difficulty or attentional differences, not the claim of representational differences being argued for here.

We hope that our explanations and clarifications above adequately address the reviewer’s concerns. We would like to reiterate that we did not directly compare the two tasks. Rather, we first identified the neural representations of sequential distance and duration, and then examined how these representations differed across tasks. It is unclear to us how the overall difference in task difficulty or attentional demands could lead to the observed pattern of results.

By determining where the neural representations were consistent and where they diverged, we were able to differentiate brain regions that encode temporal information allocentrically from those that represent temporal information in a perspective-dependent manner, modulated by task demands.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

Xu et al. used fMRI to examine the neural correlates associated with retrieving temporal information from an external compared to internal perspective ('mental time watching' vs. 'mental time travel'). Participants first learned a fictional religious ritual composed of 15 sequential events of varying durations. They were then scanned while they either (1) judged whether a target event happened in the same part of the day as a reference event (external condition); or (2) imagined themselves carrying out the reference event and judged whether the target event occurred in the past or will occur in the future (internal condition). Behavioural data suggested that the perspective manipulation was successful: RT was positively correlated with sequential distance in the external perspective task, while a negative correlation was observed between RT and sequential distance for the internal perspective task. Neurally, the two tasks activated different regions, with the external task associated with greater activity in the supplementary motor area and supramarginal gyrus, and the internal condition with greater activity in default mode network regions. Of particular interest, only a cluster in the posterior parietal cortex demonstrated a significant interaction between perspective and sequential distance, with increased activity in this region for longer sequential distances in the external task, but increased activity for shorter sequential distances in the internal task. Only a main effect of sequential distance was observed in the hippocampus head, with activity being positively correlated with sequential distance in both tasks. No regions exhibited a significant interaction between perspective and duration, although there was a main effect of duration in the hippocampus body with greater activity for longer durations, which appeared to be driven by the internal perspective condition. On the basis of these findings, the authors suggest that the hippocampus may represent event sequences allocentrically, whereas the posterior parietal cortex may process event sequences egocentrically.

We sincerely appreciate the reviewers for providing an accurate, comprehensive, and objective summary of our study.

Strengths:

The topic of egocentric vs. allocentric processing has been relatively under-investigated with respect to time, having traditionally been studied in the domain of space. As such, the current study is timely and has the potential to be important for our understanding of how time is represented in the brain in the service of memory. The study is well thought out, and the behavioural paradigm is, in my opinion, a creative approach to tackling the authors' research question. A particular strength is the implementation of an imagination phase for the participants while learning the fictional religious ritual. This moves the paradigm beyond semantic/schema learning and is probably the best approach besides asking the participants to arduously enact and learn the different events with their exact timings in person. Importantly, the behavioural data point towards successful manipulation of internal vs. external perspective in participants, which is critical for the interpretation of the fMRI data. The use of syllable length as a sanity check for RT analyses, as well as neuroimaging analyses, is also much appreciated.

We thank the reviewer for the positive and encouraging comments.

Weaknesses/Suggestions:

Although the design and analysis choices are generally solid, there are a few finer details/nuances that merit further clarification or consideration in order to strengthen the readers' confidence in the authors' interpretation of their data.

(1) Given the known behavioural and neural effects of boundaries in sequence memory, I was wondering whether the number of traversed context boundaries (i.e., between morning-afternoon, and afternoon-evening) was controlled for across sequential length in the internal perspective condition? Or, was it the case that reference-target event pairs with higher sequential numbers were more likely to span across two parts of the day compared to lower sequential numbers? Similarly, did the authors examine any potential differences, whether behaviourally or neurally, for day part same vs. day part different external task trials?

We thank the reviewer for the thoughtful comments. When we designed the experiment, we minimized the correlation between the sequential distance between the target and reference events and whether the reference and target events occurred within the same or different parts of the day (coded as Same = 0, Different = 1). The point-biserial correlation coefficient between these two variables across all the trials within the same run were controlled below 0.2.

To investigate the effect of day-part boundaries on behavior, as well as the contribution of other factors, we conducted a new linear mixed-effects model analysis incorporating four additional variables. They are whether the target and the reference events are within the same or different parts of the day (i.e., Same vs. Different), whether the target event is in the future or the past of the reference event (i.e., Future vs. Past), and the interactions of the two factors with Task Type (i.e., internal- vs. external-perspective task).

The results are largely the same as the original one in the table: There was a significant main effect of Syllable Length, and the interaction effects between Task Type and Sequence Distance and between Task Type and Duration remain significant. What's new is we also found a significant interaction effect between Task Type and Same vs. Different.

As shown in the Figure 2—figure supplement 1, this Same vs. Different effect was in line with the effect of Sequential Distance, with two events in the same and different parts of the day corresponding to the short and long sequential distances. Given that Sequential Distance had already been considered in the model, the effect of parts of the day should result from the boundary effect across day parts or the chunking effect within day parts, i.e., the sequential distance across different parts of the day was perceived longer while the sequential distance within the same parts of the day was perceived shorter. We have incorporated these findings into the manuscript.

Neurally, to further verify that the significant effects of sequential distance were not driven by its weak correlation with the Same/Different judgment or other potential confounding factors, we constructed another GLM that incorporated three additional parametric modulators: the sequence position of the target event (ranging from 1 to 15) and the behavioral responses (Future vs. Past in the internal-perspective task; Same vs. Different in the external-perspective task, coded as 0 and 1). The significant findings were unaffected.

(2) I would appreciate further insight into the authors' decision to model their task trials as stick functions with duration 0 in their GLMs, as opposed to boxcar functions with varying durations, given the potential benefits of the latter (e.g., Grinband et al., 2008). I concur that in certain paradigms, RT is considered a potential confound and is taken into account as a nuisance covariate (as the authors have done here). However, given that RTs appear to be critical to the authors' interpretation of participant behavioural performance, it would imply that variations in RT actually reflect variations in cognitive processes of interest, and hence, it may be worth modelling trials as boxcar functions with varying durations.

We appreciate the reviewer’s insightful comment on this important issue. Whether to control for RT’s influence on fMRI activation is indeed a long-standing paradox. On the one hand, RT reflects underlying cognitive processes and therefore should not be fully controlled for. On the other hand, RT can independently influence neural activity, as several brain networks vary with RT irrespective of the specific cognitive process involved—a domain-general effect. For example, regions within the multiple-demand network are often positively correlated with RT across different cognitive domains.

Our strategy in the manuscript is to first present the results without including RT as a control variable and then examine whether the effects are preserved after controlling for RT. In the revised manuscript, we have clarified this approach (Page 13): “Here, changes in activity levels within the PPC were found to align with RT. Whether to control for RT’s influence on fMRI activation represents a well-known paradox. On the one hand, RT reflects underlying cognitive processes and therefore should not be fully controlled for. On the other hand, RT can independently influence neural activity, as several brain networks vary with RT irrespective of the specific cognitive process involved—a domain-general effect. For instance, regions within the multiple-demand network are often positively correlated with RT and task difficulty across diverse cognitive domains (e.g., Fedorenko et al., 2013; Mumford et al., 2024). To evaluate the second possibility, we conducted an additional control analysis by including trial-by-trial RT as a parametric modulator in the first-level model (see Methods). Notably, the same PPC region remained the only area in the entire brain showing a significant interaction between Task Type and Sequential Distance (voxel-level p < 0.001, clusterlevel FWE-corrected p < 0.05). This finding indicates that PPC activity cannot be fully attributed to RT. Furthermore, we do not interpret the effect as reflecting a domain-general RT influence, as regions within the multiple-demand system—typically sensitive to RT and task difficulty—did not exhibit significant activation in our data.”

The reason we did not use boxcar functions with varying durations in our original manuscript is that we also applied parametric modulation in the same model. In the parametric modulation, all parametric modulators inherit the onsets and durations of the events being modulated. Consequently, the modulators would also take the form of boxcar functions rather than stick functions—the height of each boxcar reflecting the parameter value and its length reflecting the RT. We were uncertain whether this approach would be appropriate, as we have not encountered other studies implementing parametric modulation in this manner.

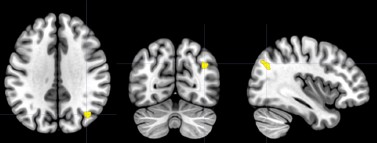

For exploratory purposes, we also conducted a first-level analysis using boxcar functions with variable durations. The same PPC region remained the strongest area in the entire brain that shows an interaction effect between Task Type and Sequential Distance. However, the cluster size was slightly reduced (voxel-level p < 0.001, cluster-level FWE-corrected p = 0.0610; see the Author response image 1 below). The cross indicates the MNI coordinates at [38, –69, 35], identical to those shown in the main results (Figure 4A).

Author response image 1.

(3) The activity pattern across tasks and sequential distance in the posterior parietal cortex appears to parallel the RT data. Have the authors examined potential relationships between the two (e.g., individual participant slopes for RT across sequential distance vs. activity betas in the posterior parietal cortex)?

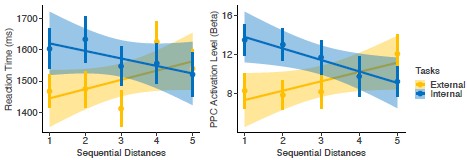

We thank the reviewer for this helpful suggestion. As shown in the Author response image 2, the interaction between Task Type and Sequential Distance was a stronger predictor of PPC activation than of RT. Because PPC activation and RT are measured on different scales, we compared their standardized slopes (standardized β) measuring the change in a dependent variable in terms of standard deviations for a one-standard-deviation increase in an independent variable. The standardized β for the Task Type × Sequential Distance interaction was −0.30 (95% CI [−0.42, −0.19]) for PPC activation and −0.21 (95% CI [−0.30, −0.13]) for RT. The larger standardized effect for PPC activation indicates that the Task Type × Sequential Distance interaction was a stronger predictor of neural activation than of behavioral RT.

Author response image 2.

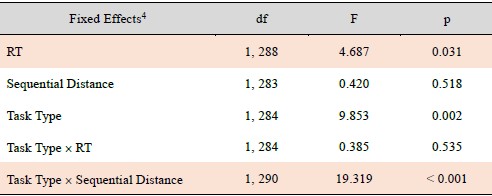

A more relevant question is whether PPC activation can be explained by temporal information (i.e., the sequential distance) independently of RT. To test this, we included both Sequential Distance and RT in the same linear mixed-effects model predicting PPC Activation Level. As shown in the Author response table 1, although RT independently influenced PPC activation (F(1, 288) = 4.687, p = 0.031), the interaction between Task Type and Sequential Distance was a much stronger independent predictor (F(1, 290) = 19.319, p < 0.001).

Author response table 1.

PPC Activation Level Predicted by Sequential Distance and RT

(3) Linear Mixed Model Formula: PPC Activation Level ~ 1 + Task Type * (Sequential Distance + RT) + (1 | Participant)

(4) There were a few places in the manuscript where the writing/discussion of the wider literature could perhaps be tightened or expanded. For instance:

(i) On page 16, the authors state 'The negative correlation between the activation level in the right PPC and sequential distance has already been observed in a previous fMRI study (Gauthier & van Wassenhove, 2016b). The authors found a similar region (the reported MNI coordinate of the peak voxel was 42, -70, 40, and the MNI coordinate of the peak voxel in the present study was 39, -70, 35), of which the activation level went up when the target event got closer to the self-positioned event. This finding aligns with the evidence suggesting that the posterior parietal cortex implements egocentric representations.' Without providing a little more detail here about the Gauthier & van Wassenhove study and what participants were required to do (i.e., mentally position themselves at a temporal location and make 'occurred before' vs. 'occurred after' judgements of a target event), it could be a little tricky for readers to follow why this convergence in finding supports a role for the posterior parietal cortex in egocentric representations.

We appreciate the reviewer’s comments. In the revised manuscript, we have provided a more detailed explanation of Gauthier and van Wassenhove’s study (Page 17): “The negative correlation between the activation level in the right PPC and sequential distance has already been observed in a previous fMRI study by Gauthier & van Wassenhove (2016b). In their study, the participants were instructed to mentally position themselves at a specific time point and judge whether a target event occurred before or after that time point. The authors identified a similar brain region (reported MNI coordinates of the peak voxel: 42, −70, 40), closely matching the activation observed in the present study (MNI coordinates of the peak voxel: 39, −70, 35). In both studies, activation in this region increased as the target event approached the self-positioned time point, which aligns with the evidence suggesting that the posterior parietal cortex implements egocentric representations.”

(ii) Although the authors discuss the Lee et al. (2020) review and related studies with respect to retrospective memory, it is critical to note that this work has also often used prospective paradigms, pointing towards sequential processing being the critical determinant of hippocampal involvement, rather than the distinction between retrospective vs. prospective processing.

We sincerely thank the reviewer for highlighting these important points. In response, we have revised the section of the Introduction discussing the neural underpinnings of duration (Pages 3-4). “Neurocognitive evidence suggests that the neural representation of duration engages distinct brain systems. The motor system—particularly the supplementary motor area—has been associated with prospective timing (e.g., Protopapa et al., 2019; Nani et al., 2019; De Kock et al., 2021; Robbe, 2023), whereas the hippocampus is considered to support the representation of duration embedded within an event sequence (e.g., Barnett et al., 2014; Thavabalasingam et al., 2018; see also the comprehensive review by Lee et al., 2020).”

(iii) The authors make an interesting suggestion with respect to hippocampal longitudinal differences in the representation of event sequences, and may wish to relate this to Montagrin et al. (2024), who make an argument for the representation of distant goals in the anterior hippocampus and immediate goals in the posterior hippocampus.

We thank the reviewer for bringing this intriguing and relevant study to our attention. In the Discussion of the manuscript, we have incorporated it into our discussion (Page 21): “Evidence from the spatial domain has suggested that the anterior hippocampus (or the ventral rodent hippocampus) implements global and gist-like representations (e.g., larger receptive fields), whereas the posterior hippocampus (or the dorsal rodent hippocampus) implements local and detailed ones (e.g., finer receptive fields) (e.g., Jung et al., 1994; Kjelstrup et al., 2008; Collin et al., 2015; see reviews by Poppenk et al., 2013; Robin & Moscovitch, 2017; see Strange et al., 2014 for a different opinion). Recent evidence further shows that the organizational principle observed along the hippocampal long axis may also extend to the temporal domain (Montagrin et al., 2024). In that study, the anterior hippocampus showed greater activation for remote goals, whereas the posterior hippocampus was more strongly engaged for current goals, which are presumed to be represented in finer detail.”

Reviewing Editor Comments:

While both reviewers acknowledged the significance of the topic, they raised several important concerns. We believe that providing conceptual clarification, adding important methodological details, as well as addressing potential confounds will further strengthen this paper.

We thank the editor for the suggestions.

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for the authors):

(1) Please, provide the actual ethical approval #.

We have added the ethical approval number in the revised manuscript (P 36): “The ethical committee of the University of Trento approved the experimental protocol (Approval Number 2019-018),”

(2) Thirty-two participants were tested. Please report how you estimated the sample size was sufficient to test your working hypothesis.

We thank the editor for pointing out this omission. In the revised manuscript, we have added an explanation for our choice of sample size (p. 36): “The sample size was chosen to align with the upper range of participant numbers reported in previous fMRI studies that successfully detected sequence or distance effects in the hippocampus (N = 15–34; e.g., Morgan et al., 2011; Howard et al., 2014; Deuker et al., 2016; Garvert et al., 2017; Theves et al., 2019; Park et al., 2021; Cristoforetti et al., 2022).”

(3) All MRI figures: please orient the reader; left/right should be stated.

In the revised manuscript, we have added labels to all MRI figures to indicate the left and right hemispheres.

(4) In Figure 3A-B, the clear lateralization of the activation is not discussed in the Results or in the Discussion. Was it predicted?

We thank the editors for highlighting this important point regarding hemispheric lateralization. The right-lateralization observed in our findings is indeed consistent with previous literature. In the revised manuscript, we have expanded our discussion to emphasize this aspect more clearly.

For the parietal cortex, we now note (Page 17-18): “The negative correlation between activation in the right posterior parietal cortex (PPC) and sequential distance has previously been reported in an fMRI study by Gauthier and van Wassenhove (2016b). In their paradigm, participants were instructed to mentally position themselves at a specific time point and judge whether a target event occurred before or after that point. The authors identified a similar region (peak voxel MNI coordinates: 42, −70, 40), closely corresponding to the activation observed in the present study (peak voxel MNI coordinates: 39, −70, 35). In both studies, activation in this region increased as the target event approached the self-positioned time point, consistent with evidence suggesting that the posterior parietal cortex supports egocentric representations. Neuropsychological studies have further shown that patients with lesions in the bilateral or right PPC exhibit ‘egocentric disorientation’ (Aguirre & D’Esposito, 1999), characterized by an inability to localize objects relative to themselves (e.g., Case 2: Levine et al., 1985; Patient DW: Stark, 1996; Patients MU: Wilson et al., 1997, 2005).”

For the hippocampus, we have added (Page 19): “Previous research has shown that hippocampal activation correlates with distance (e.g., Morgan et al., 2011; Howard et al., 2014; Garvert et al., 2017; Theves et al., 2019; Viganò et al., 2023), and that distributed hippocampal activity encodes distance information (e.g., Deuker et al., 2016; Park et al., 2021). Most studies have reported hippocampal ePects either bilaterally or predominantly in the right hemisphere, whereas only one study (Morgan et al., 2011) found the ePect localized to the left hippocampus.”