Abstract

For years, the airway microbiota have been theorized to be gatekeepers of respiratory health, as pathogens entering the airway make contact with resident microbes prior to or coincident with their interaction with host cells. Thus, modification of the native airway community may serve as a means of altering the local environment in favor of health. In this work, we hypothesize that synthetic bacterial communities introduced into the airway can serve as prophylactic countermeasures against infection by Burkholderia thailandensis in mice. We demonstrate that understanding of antagonistic interactions between a pathogen and airway microbiota in vitro can guide identification of probiotics with protective capabilities in vivo. Specifically, we show that niche overlap between the probiotic and pathogen is indicative of probiotic performance in vivo. This work serves as a foundation for the rational design of probiotic communities for protection against and treatment of respiratory infections.

Introduction

Every mammalian body compartment that opens to the outside world has microbial life associated with it1. Until recently, the healthy lung was thought to be a sterile environment; however, recent work has demonstrated that the lower respiratory tract is colonized by a complex and roughly stable microbiome that impacts the health of the host2–4. For years, the airway microbiota have been theorized to be gatekeepers of respiratory health, as pathogens entering the airway make contact with its microbiota prior to or coincident with their interactions with host cells3. While the latter interactions have been studied in detail, little is known about pathogen-microbiome interactions in the airway.

It has been hypothesized that pathogen establishment in the airway could be halted by its microbiota through either indirect or direct competition with the pathogen3,5,6. During indirect competition, airway microbiota would modulate the host immune response to increase surveillance, promoting rapid recognition and clearance of foreign microbes including pathogenic organisms. During direct competition, the airway microbiota would competitively exclude a pathogen through production of inhibitory specialized metabolites, and/or by occupying a nutritional niche that would otherwise be used by the pathogen. Enhancement of these defense mechanisms might be achieved through addition of health-promoting microbes (probiotics) directly to the lower airway, an approach that has been demonstrated to prevent pneumococcal and Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection previously7,8.

While these studies have shed light on the utility of lower airway probiotics for preventing two specific infections, greater understanding of the principles that dictate probiotic efficacy would allow rapid identification of probiotics with therapeutic potential against many pathogenic targets. To enable development of these therapies in the future, pipelines for probiotic nomination need to be made which can rapidly and cheaply identify effective therapies. Further, systematic analysis of the mechanism of action of these probiotics would allow fine-tuned control of their activity allowing for more reliable therapeutic outcomes in the clinic.

Here, we seek to fill this gap in knowledge by systematically characterizing factors that make efficacious lower airway probiotics that can competitively exclude a model pathogen, Burkholderia thailandensis (Bt), from the lung environment. Specifically, we hypothesize that negative microbial interactions between a probiotic and pathogen better protect the host against infection. Our systematic study of the microbial ecology of these organisms enables development of a pipeline for nomination of effective single and multi-organism probiotics that, to this point, remain underdeveloped. We show that using our pipeline, we can accurately identify pairwise combinations of organisms with enhanced activity against Bt. Finally, we test the ability of these prophylactically administered probiotics to promote survival during a challenge with Bt in vivo.

Results

Isolation and characterization of candidate probiotics

To develop a system for testing the efficacy of lower airway probiotics in preventing infection, it was first necessary to identify a suitable pathogen to investigate. Burkholderia thailandensis (Bt) is a pathogen of mice that is genomically similar to several human pathogens including Burkholderia pseudomallei, Burkholderia mallei and organisms of the Burkholderia cepacia complex, the latter of which poses a high risk of mortality for cystic fibrosis patients9–13. Thus, Burkholderia thailandensis is an appropriate subject of study for our purposes as it is safe, infectious in mice and a good model of several pathogens with clinical relevance.

To acquire candidate probiotics for use in the lower airway, we sought organisms which would be able to survive in the lower airway for an extended period of time and be capable of tolerating its low-nutrient environment14. We hypothesized that organisms directly isolated from the airway would fulfill this criterion, as they are already well-adapted to the environment and may be more immunologically tolerated by the host. To isolate candidate probiotics, the trachea and lungs were collected from C57Bl/6j mice, homogenized, and plated onto five different solid growth media, either directly or after an initial period of culture in blood bottles. Tissues that should be sterile (liver and spleen) were collected from the same mice and processed in parallel, in order to recover any contaminants [“background” (B) strains] inadvertently introduced through our bacterial isolation procedures. Bacterial colonies were repeatedly streaked on LB agar to recover clonal isolates for whole-genome sequencing. In total, 28 isolates recovered from the lower airway tissues were further characterized for use as airway probiotics.

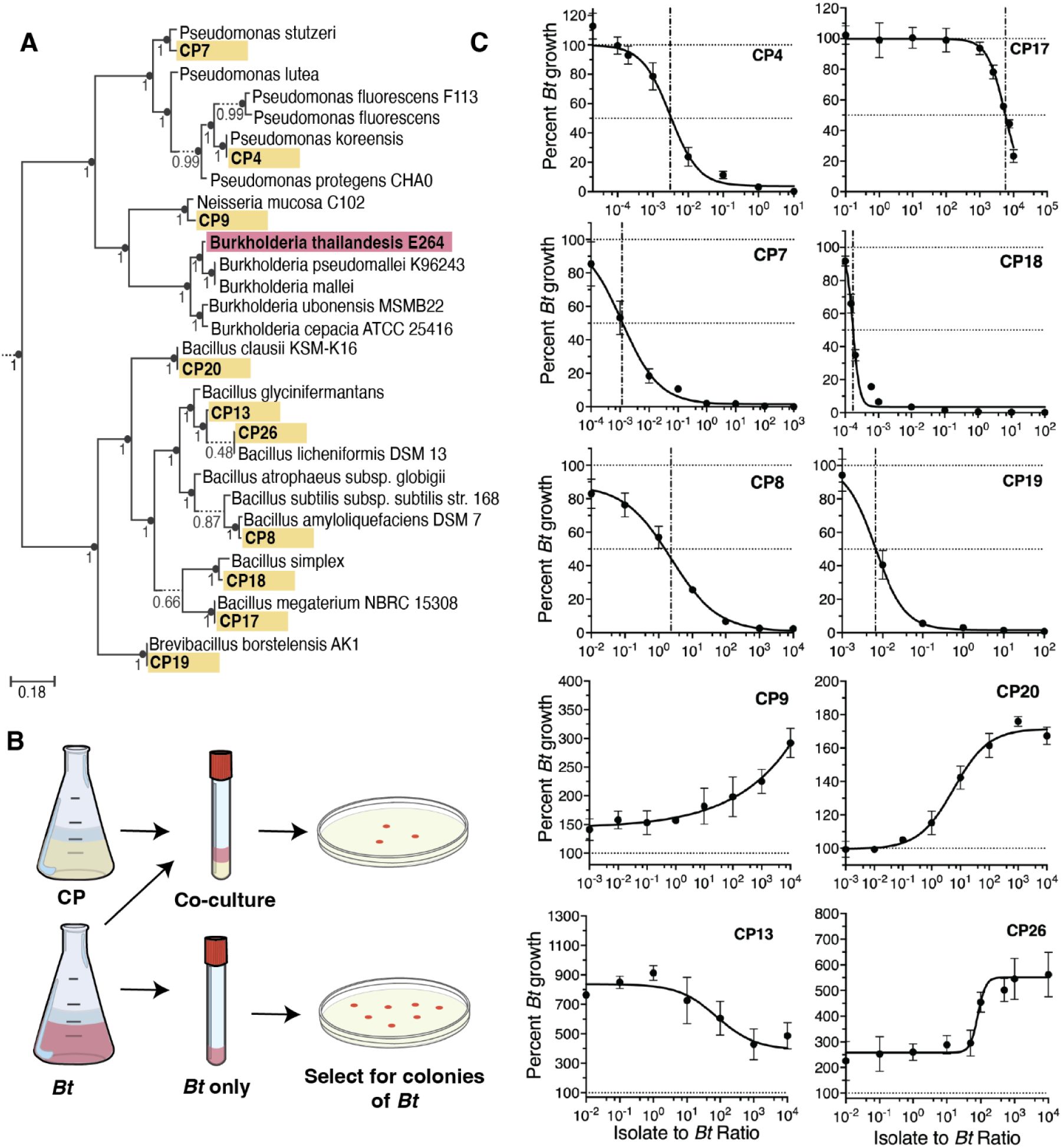

Prior work on the lung microbiome has led to the widely held hypothesis that many of its constituents originate from the oral and/or nasal microbiome and are unable to actively replicate and persist in the lower airway15,16. We therefore sought to identify airway isolates that are capable of active growth in the lower respiratory tract, with the supposition that they should be better equipped to re-colonize the airway and compete against an invading pathogen. To do this, the airway isolates were cultured in lung simulating medium (LSM), which is based on the nutrient composition of sputum samples from cystic fibrosis patients, and therefore is thought to approximate the nutritional environment of the lower respiratory tract17–20. We found that 10 of 28 airway isolates tested were capable of robust growth (>1 doubling within 48 hours) in LSM (Figure S1). These 10 isolates, and model pathogen Bt, are arrayed on a phylogenomic tree (Figure 1A), and are henceforth referred to as candidate probiotics (CPs).

Characterization of CP activity against B. thailandensis in vitro.

(A) Phyloge nomic tree of CPs (yellow) and model pathogen B. thailandensis (Bt) (red), interspersed amongst publicly available genomes (no color). (B) Schematic of competition assay used to test in vitro inhibitory capabilities. Percent growth of Bt is calculated as the CFU in co-culture at 24 hours divided by the CFU in the Bt monoculture at 24 hours multiplied by 100. Co-culture inhibition was tested for multiple starting densities of CP (see Figure 1C x-axis). Starting densi ty of Bt and CP at a 1:1 ratio are 3.33×104 CFU/ml per organism. Bt monoculture is inoculated at 3.33×104 CFU/ml. (C) Dose-response curves for CPs against Bt. Relative IC50 is denoted with a vertical dashed-dotted line, and 100% and 50% growth are denoted with horizontal dotted lines. Percent growth at each density is represented as mean± SEM.

The phylogenetic assignments of the CPs were compared to those of airway microbiome constituents previously identified through 16S rRNA profiling of mouse airway tissue21–25. This analysis revealed that the taxonomic groups to which the CPs belong are well represented in the mouse airway microbiome (Tables S1-3). For example, we found that all 9 of the species to which the CPs belong were detected in at least 1 of 4 previous airway microbiome profiling efforts, with 7 of the 9 species detected in more than 1 profiling effort. In contrast, only 1 of the 9 species to which the B strains (contaminants recovered from liver and spleen) belong was detected, in only 1 of the 4 profiling efforts. Similarly, 3 of the 4 genera to which CPs belong were detected in all 4 profiling efforts (whereas for B strains, only 3 of 9 genera were detected in all 4 efforts); and all 4 of the families to which the CPs belong were detected in all 4 profiling efforts (whereas for B strains, only 6 of 8 families were detected in all 4 efforts). These results indicate that the CPs belong to taxonomic groups that are typically well represented in mouse airway microbiome, consistent with the idea that they are airway microbiome constituents that have been recovered into culture.

Next, we aimed to identify CPs capable of inhibiting Bt during co-culture in LSM, with the hypothesis that they might also inhibit Bt in the lower respiratory tract and therefore serve as efficacious probiotics. Expression of antagonistic phenotypes is dependent on several factors including the cell density relative to the available resources26,27. Accordingly, we decided to assay interbacterial interactions in LSM across varying cell densities, with the hypothesis that this would enable us to capture information about CP potency. Each CP was co-cultured with Bt in LSM at different relative ratios (Figure 1B). We found that the CPs showed a range of activities, including negative interactions (Figure 1C top 6 plots) and positive interactions (Figure 1C lower 4 plots) with Bt; the potency of each CP, as indicated by IC50 value, is shown in Table 1.

Summary of pathogen inhibition by CPs.

Relative IC50 values and 95% confidence intervals {95% Cl) are shown for each inhibitory CP. Not determined (n.d.) indicates that a value could not be measured. CPs are listed in order of decreasing NI values.

Production of a specialized metabolite plays a role in the antagonistic activities of CP8

Next, we sought to better understand the mechanism(s) of the observed negative interactions. First, we hypothesized that those CPs that strongly inhibit Bt may do so by simply growing at a faster rate than the pathogen thus dominating the environment. However, we found no correlation between doubling time of the CPs in LSM and their Bt antagonism (r = −0.21, P = 0.155, 95% CI [−0.47 to 0.088], N = 49). It has been shown previously that bacteriophages can modulate interbacterial competition, and some that can target Bt have been identified28–31; therefore, we next hypothesized that some of the negative interactions between CPs and Bt might be mediated through production of Bt-targeting phages. To test this, we attempted to recover phages from each CP using standard methods32,33, and tested the resulting product against Bt in plaque assays (Figure S2). We found that none of the CPs appeared to produce a phage that could effectively lyse Bt.

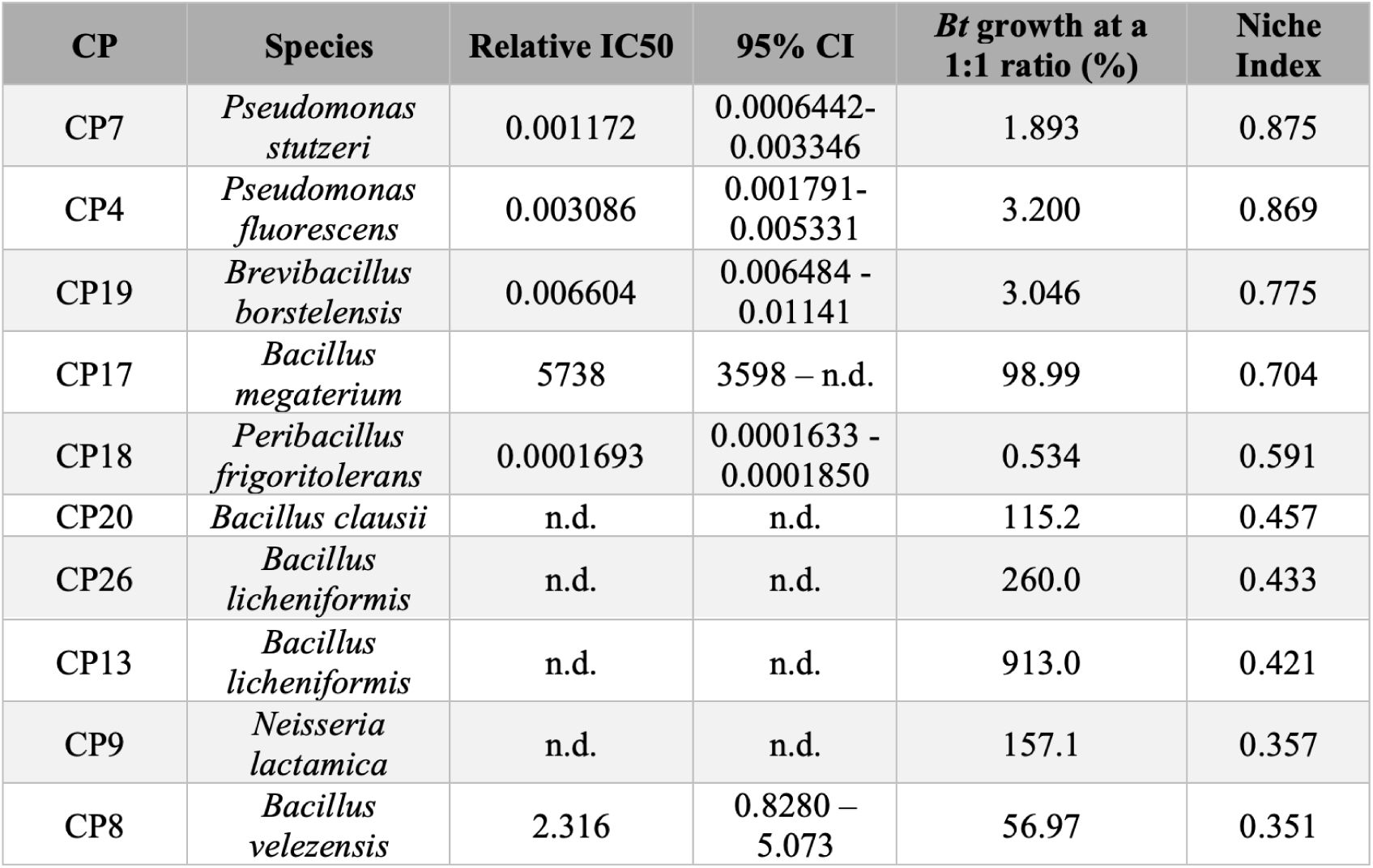

Given this information, we next hypothesized that these negative interactions could be direct, through chemical attack (ie. production of inhibitory metabolites); or indirect, through occupying a shared metabolic niche with the pathogen. First, we investigated the presence of inhibitory metabolites by growing Bt in sterilized co-culture supernatant from itself and a CP. We predicted that if Bt-inhibiting secondary metabolites were produced by a given CP during co-culture in LSM, then the conditioned medium recovered from the co-culture would inhibit growth of Bt. To test this, each negatively-interacting CP was co-cultured with Bt for 72 hours, filter sterilized, and combined with double-concentrated LSM to serve as medium for Bt growth curves (Figure 2A). We found that the co-culture supernatant from only one of the airway isolates (CP8) significantly reduced growth of Bt compared to supernatant from a Bt monoculture (negative control) (Figure 2B). This indicated that CP8 likely produced a specialized metabolite and was engaging in interference competition. To confirm our findings, we performed agar diffusion assays on all inhibitory CPs and found that, aside from CP8, none produced a zone of inhibition on a lawn of Bt (data not shown).

Production of a specialized metabolite plays a role in the antagonistic activities of CPS.

(A) Schematic representation of supernatant inhibition experiment workflow. Superna tant from a Bt and CP co-culture or from Bt monoculture (supernatant) is mixed 1:1 with 2x LSM. This mixture is used as the growth medium for subsequent Bt growth curves. Fold-change in Bt growth is calculated by dividing the maximum growth of Bt in co-culture supernatant by the maximum growth of Bt grown in supernatant from itself. (B) Left: Heatmap of fold-change in max CFU of Bt grown in supernatant from each inhibitory CP and Bt co-cul ture relative to Bt grown in supernatant from itself. Co-culture supernatant was collected at 72 hours. A fold-change of 1 indicates no difference in growth in co-culture supernatant compared to Bt growth in supernatant from itself. A fold-change less than 1 indicates a reduction in patho gen growth. Right: Boxplot of growth inhibition by CP8 supernatant. Data are represented as mean± SD. (C) Agar diffusion assays testing the CP8 wildtype strain (CP8 WT) and sfp mutant strain (CP8!:1sfp) for inhibition of Bt after 48 hours. (D) Growth curves of CP8 WT (black) and CP8!:1sfp (red) (E) Dose-response curve of CP8 WT (black) and CP8!:1sfp (red) against Bt after 24 hours of co-culture. Percent growth at each density is represented as mean ± SEM.

To understand the degree to which CP8’s secondary metabolite is responsible for mediating the competitive phenotype observed in Figure 1C, we aimed to create a knockout of this molecule in CP8. Previously, we used antiSMASH34 to identify biosynthetic gene clusters in the CP8 genome sequence, and found that CP8 likely produces 19 specialized metabolites35. A review of the literature revealed that biosynthesis of many of these specialized metabolites is dependent on Sfp, a phosphopantetheinyl transferase which catalyzes their conversion to the active holo-form36–39. Therefore, we hypothesized that knocking out the sfp gene in CP8 would yield a mutant with an inability to produce a specialized metabolite with inhibitory capabilities against Bt. A clean deletion of the sfp gene was made in CP8, and the resulting mutant (CP8Δsfp) was found to produce a smaller zone of inhibition in an agar diffusion assay, indicating that interference competition was reduced (Figure 2C). Additionally, growth curves of wildtype CP8 and the CP8Δsfp mutant were performed, which showed no growth defect in the mutant strain (Figure 2D), indicating that its reduction in interference competition was not due to a growth defect. Finally, a competition assay was performed using the CP8Δsfp mutant. The mutant showed reduced inhibitory activity compared to wildtype CP8 and, in contrast, demonstrated a positive interaction with Bt when interference competition was disrupted (Figure 2E).

Metabolic niche overlap is indicative pathogen and CP antagonism

While production of an inhibitory metabolite appeared to be the primary mode of inhibition for CP8, 5 other CPs showed a negative interaction with Bt but did not appear to produce specialized metabolites. Previous work has shown that competition for a shared metabolic niche is an important mediator of interbacterial interactions in bacterial communities40–44. Therefore, we hypothesized that inhibition of Bt by these 5 CPs may be due to metabolic niche overlap. Specifically, we postulated that passive consumption of a limiting resource by the CP could reduce the supply to Bt, thus inhibiting its growth.

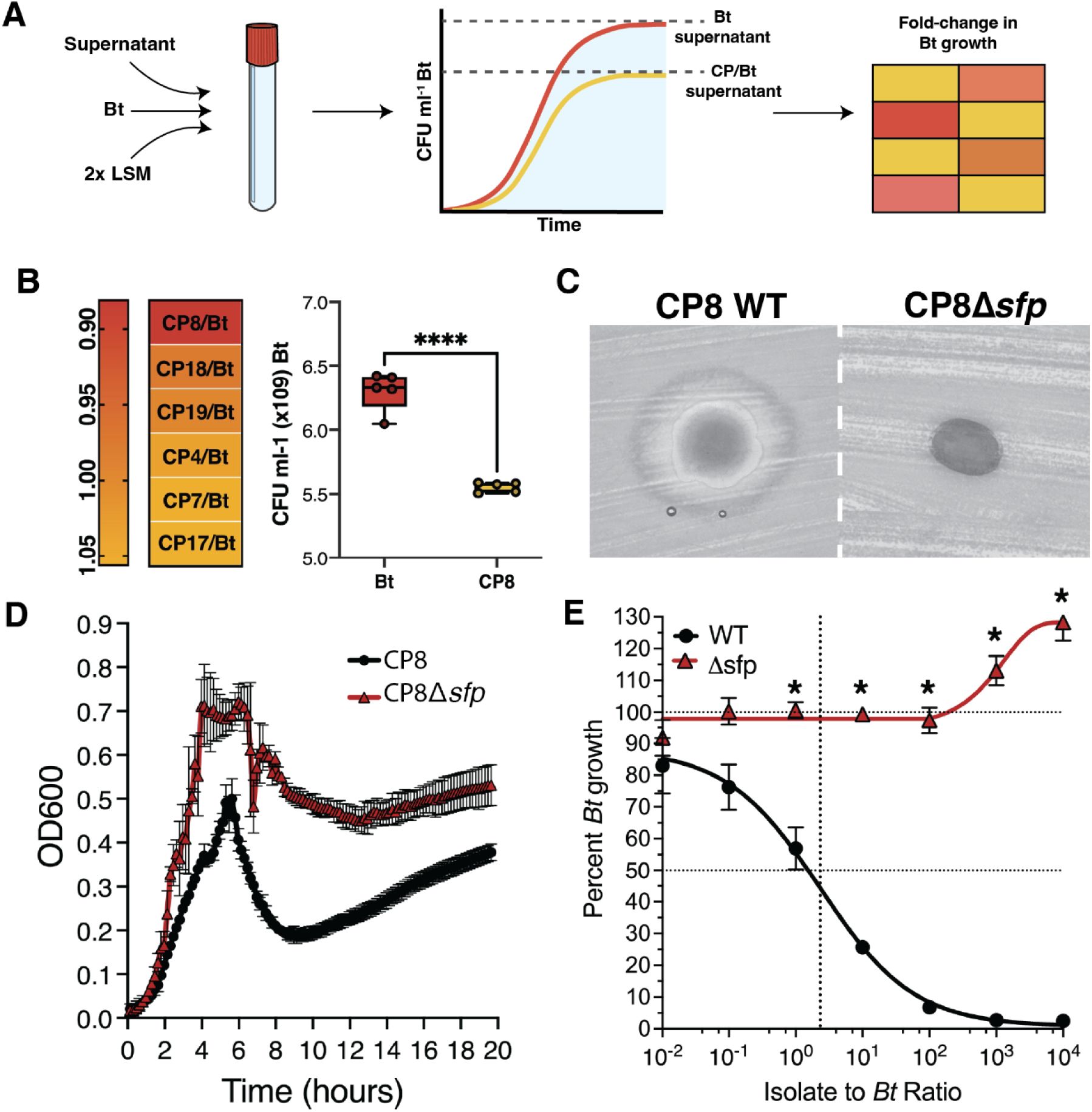

The Redfield Ratio describes the stoichiometric relationship between carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus which supports life on earth and is canonically 106:16:145. Recent work has shown that this ratio is variable across body sites, with areas like the mouth and gut being more carbon rich, and the airways being relatively carbon poor46. Similar to the upper airway, LSM is carbon limiting, with a C:N:P ratio of approximately 88:14:1. This suggests that carbon may be the limiting nutrient in the lower airway and thus, may be the limiting resource in the airway niche. We predicted that if carbon was limiting, then supplementation of LSM with additional carbon would reduce the antagonism between the CP and Bt. To test this, LSM was supplemented with 43mM glucose to increase the C:N:P ratio to 101:14:1. We observed a leftward shift of the dose-response curve for CP7 in the additional carbon condition (Figure 3A), and a significant reduction in inhibition at a 1:100 ratio (Figure 3B). A similar result was observed when the same experiment was conducted with CP19 (Figure S3). These results suggest that with increased carbon abundance there is a reduction in antagonism, consistent with the idea that, under the carbon limiting conditions of the airway, carbon is the primary nutrient for which CPs and Bt are competing.

Metabolic niche overlap is indicative of pathogen and CP antagonism.

(A) Dose-response curve for CP7 grown in unsupplemented LSM (black) or with additional glucose (red). Percent growth at each density is represented as mean ± SEM. (B) Activity of CP7 against Bt at a 1:100 ratio with or without glucose supplementation (red and gray, respec tively). Data are summarized as mean ± SD. ***P<0.001. (C) Carbon utilization heatmap for CPs and Bt. (D) Venn diagram of carbon sources utilized by CP7 and Bt. (E) Plot of rank percent Bt growth at a 1:1 ratio after 24 hours vs rank of Niche Index for each CP. Correlation is determined by Spearman rank correlation (r = −0.6367, P < 0.0001, 95% Cl [−0.7891 −0.4261], N = 49). (F) Total carbon consumed by CPs grown in combination with Bt at 36 hours (mean ± SD). Activity indicates relative amount of Bt inhibition at a 1:1 ratio from most(+++) to least(+) inhibitory. *P=0.05; **P<0.01. (G) Total electron flux at 24 hours. Red dashed line indicates the estimated abundance of Bt in each co-culture. (H) Summed electron flux of lactate (black), praline (white), and aspartic acid (gray) at 24 hours in different CP co-culture conditions (mean± SD). *P<0.05.(I) Receiver operator characteristic curve showing the ability of growth on lactate to distinguish inhibitory CPs from non-inhibitory CPs. An AUROC of 1 indi cates perfect distinction between inhibitors and non-inhibitors; an AUROC of 0.5 (dashed red line) indicates no distinction between inhibitors and non-inhibitors.

Further, we sought to explore the extent to which metabolic overlap with Bt for carbon sources could predict inhibitory capabilities of each CP. To do this, we assayed the growth of each CP and Bt in each individual carbon source from LSM to determine which carbon sources could be utilized by each organism (Figure 3C). Bt showed a wide range of metabolic potential and was able to grow on every carbon source presented except for ornithine. This is perhaps unsurprising as it has been shown previously that pathogens acquire new metabolisms in order to survive in their host47. Conversely, the CPs displayed diverse metabolic activity, with CP4 and CP7 appearing most similar to Bt (Figure 3C).

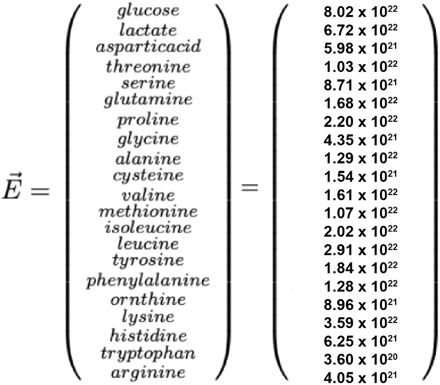

Each carbon source in LSM is used both for production of biomass as well as the primary electron donor to generate energy via aerobic respiration. In the niche exclusion hypothesis, a competitive advantage can be obtained for an organism that is able to consume those resources that would otherwise fuel aerobic respiration of a competitor. We therefore hypothesized that those CPs that are capable of sharing a greater proportion of carbon-derived electrons with Bt would have more potent antagonism of the pathogen by covering a greater percentage of the energetic niche (Figure 3D). On this assumption, we built a simple index of niche overlap which weights each carbon source in LSM utilized by a given CP by the theoretical electron contribution of that given source, with the belief that such a metric could identify probiotics capable of achieving maximal niche coverage. We hypothesized that weighting each carbon source by its theoretical electron contribution would improve the accuracy of the niche index, as those sources which contribute more electrons represent a greater proportion of the energetic niche and therefore have a potentially greater impact on antagonistic phenotypes. Niche Index (NI) is calculated as follows:

First, the number of electron equivalents generated by each carbon source is calculated assuming the complete oxidation of these sources to carbon dioxide under standard conditions. The electron equivalents are then multiplied by the total number of molecules of the carbon source in the media. This yields the total electron equivalents for each carbon source per liter of media. These values are held in vector

The weighted value for each carbon source is:

For all CPs and Bt, a carbon utilization vector is generated. If a carbon source is consumed, then i = 1, if it is not able to be consumed, then i = 0.

To calculate the Niche Index of each CP with Bt, the Hadamard product of the carbon utilizations vectors for each CP and Bt are multiplied by the weighting vector. The resulting value represents the electron equivalents utilized by both the CP and Bt. This value is divided by the electron equivalents utilized by Bt alone. Thus, the equation for Niche Index is: :

NI is higher when a given CP shares a greater number of carbon-derived electrons with Bt. To evaluate the association between the co-culture interaction with Bt and the NI of each CP, a non-parametric spearman rank-order correlation was performed with the null hypothesis that there is no monotonic association between the two variables. We found that NI is negatively associated with the co-culture growth of Bt with a given CP at a 1:1 ratio (r = −0.64, P < 0.0001, 95% CI [−0.79 −0.43], N = 49) (Table 1 and Figure 3E). Since CP8’s potency is primarily due its secondary metabolite production (Figure 2E), percent growth of the pathogen in co-culture with the CP8Δsfp mutant was used in this analysis to understand how NI relates to CP8’s interaction with Bt (Figure 3E). While here we have used Niche Index to calculate niche overlap between CPs and Bt in LSM, this model is generalizable and can be used to calculate the niche overlap between organisms in any media with a known molar carbon composition.

To confirm our hypothesis that those organisms that consume a greater number of carbon-derived electrons with Bt are more antagonistic, we performed exometabolomics on supernatants from 3 CPs. These 3 CPs represent a range of inhibition strengths and niche indexes, with CP7 being the most potent (IC50 = 0.001172 NI = 0.875), CP19 displaying moderate potency (IC50 = 0.006604 NI = 0.775) and CP8 being the least potent (IC50 = 2.316 NI = 0.351). Each of these CPs was combined with Bt at their respective IC90 and co-incubated for 36 hours. Supernatants from these CPs at 36 hours show that more potent CPs consume a statistically greater amount of carbon from the media than less potent CPs (Figure 3F). At 24 hours where the degree of inhibition of Bt by each CP is the same, more potent probiotics consume fewer carbon-derived electrons than less potent competitors (Figure 3G). This led us to hypothesize that certain carbon sources were being prioritized, allowing more antagonistic CPs to have the same net effect on Bt while consuming fewer electrons. Further, we speculated that if high priority carbon sources were to be identified, perhaps the consumption of a smaller set of these high priority carbon sources could predict activity with similar accuracy to the Niche Index.

From the exometabolomics data, consumption of three carbon sources, lactate, proline and aspartic acid are prioritized more at 24 hours by the most potent candidate probiotic, CP7, than the least potent, CP8 (Figure 3H). Furthermore, we found that a CP’s ability to generate biomass on lactate (the second most abundant carbon source in LSM) was a good predictor of its ability to inhibit the pathogen (Figure 3I), suggesting that the ability to consume lactate in co-culture may be important for pathogen control. Overall, these results indicate that consumption of specific resources can have an especially strong influence on niche exclusion, with consumption of a specific carbon source (lactate) appearing to play a key role in niche exclusion of Bt by the most potent of the CPs (CP7). While these results are promising building blocks for the development of a metric of activity based upon a smaller feature set, a larger screen of candidate probiotics may be necessary to understand the generalizability of these features. Further, future efforts to develop this model should take into account a CP’s uptake rate for a given resource as this may influence antagonism and reveal features of the metabolic niche that have disproportionate significance to interbacterial interactions.

Niche overlap aids in the identification of efficacious multi-organism probiotics

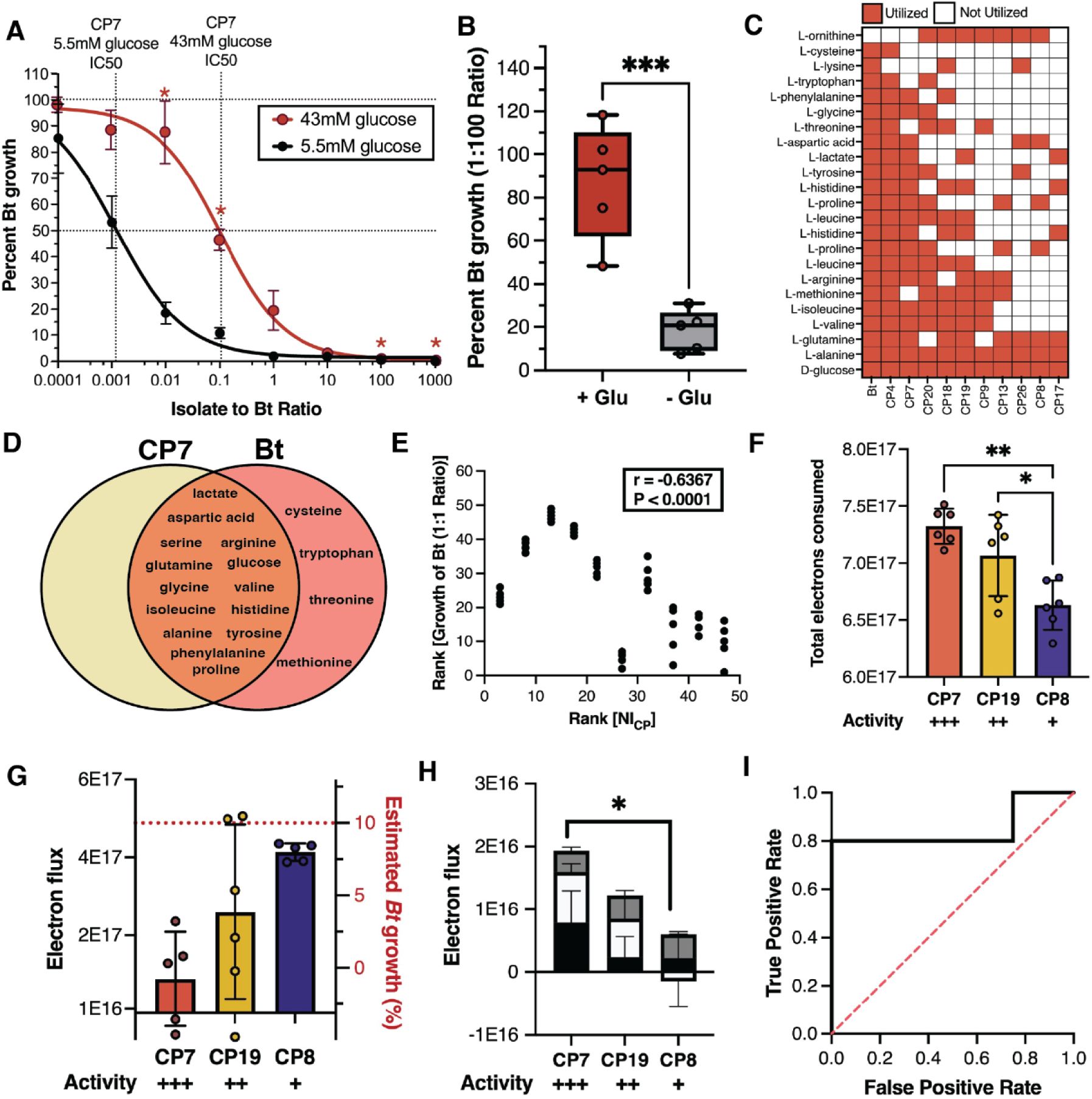

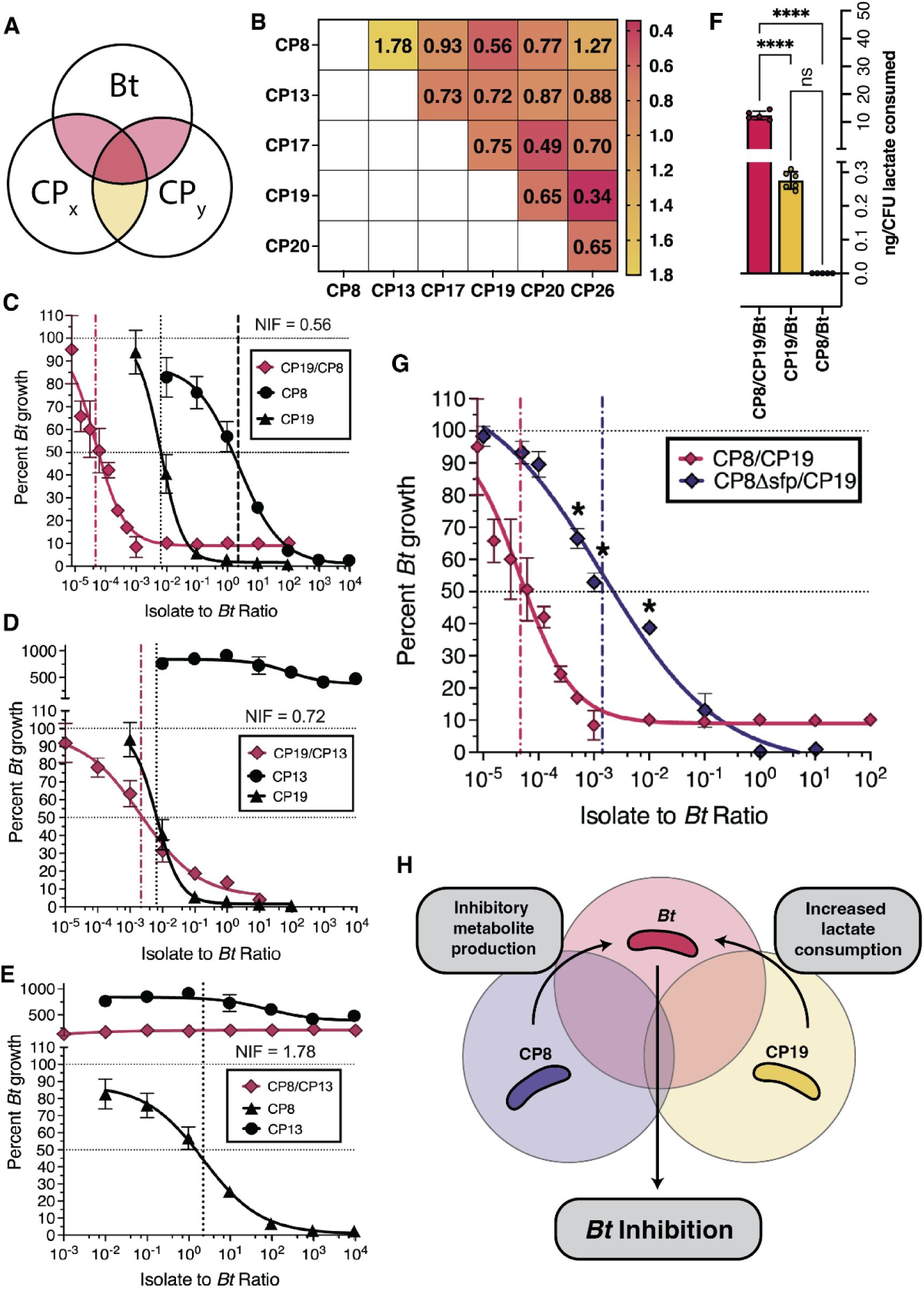

While our work showed that 6 of the CPs were potent inhibitors of Bt growth in co-culture, 4 were poor inhibitors or actually promoted Bt growth (Figure 1). Having found that NI is well correlated with CP activity in vitro, we hypothesized that this metric could be altered to identify pairwise combinations of poor-performing CPs with enhanced antagonism. To do this, we created a new metric, the Niche Index Fraction (NIF), which is calculated by generating the NI between two CPs and dividing this value by the NI of the two CPs and Bt (Figure 4A). We hypothesized that combinations with lower NIF values would have optimal coverage of the Bt niche space while minimizing niche overlap between two CPs. Thus, low NIF values might indicate combinations with enhanced inhibition of the pathogen compared to each CP alone. NIF is calculated as follows:

Niche overlap aids in identification of efficacious CP combinations.

(A) Venn diagram representa tion of the Niche Index Fraction (NIF) calculation. Yellow represents the fraction numerator and red the denomi nator. (B) Heatmap of NIF values for each colonizing CP. (C) Dose-response curve for the CP8/CP19 combina tion (mean ± SEM). (D) Dose-response curve for the CP19/CP13 combination (mean ± SEM). (E) Dose-re sponse curve for the CP13/CP8 combination (mean± SEM). (F) Lactate consumed (as determined via GC-TOF) for 3 conditions, normalized to CFU of each CP inoculated (mean ± SD). ****P<0.0001. (G) Dose-response curve for the CP8/CP19 (red) and CP8sfp/CP19.Llsfp (black) combinations. (H) Schematic of the proposed mechanism for Bt inhibition by the CP8/CP19 combination. CP8 produces a specialized metabolite that inhibits growth of the Bt. Additionally, increased lactate consumption by CP19 in the presence of CP8 further reduces Bt growth. Overall, minimal niche overlap between the CPs, and high overlap with Bt, allows for further inhibition of Bt with minimal inter-GP antagonism.

First, the overlap between two CPs is generated and is weighted by the relative electron contribution of each carbon source

Total carbon-derived electron utilization is calculated for both CPs

For which

Thus the niche overlap between two CPs is

The niche overlap between two CPs and Bt is thus

We calculated NIF for every pairwise combination of the 7 least antagonistic CPs from Figure 1. This generated a matrix of CP combinations and their respective NIF values (Figure 4B). To test this metric’s capability to identify inhibitory combinations of CPs, we chose to evaluate pairwise combinations with the three lowest NIF values, a moderate value and a high value using competition assays.

In these experiments, two CPs were combined at a 1:1 ratio such that the total CP concentration at a given ratio was the same as their individual CP counterparts. This enabled us to directly compare activity of an individual CP and the activity of a combination of two CPs at a given ratio as the total cell density was the same in each. From competition assays, we determined that NIF was able to predict combinations with enhanced and reduced Bt antagonism as reflected by their relative IC50 values (Figure 4C,D,E, Figure S4 and Table S4).

For one combination, CP8 and CP19, we sought to understand the mechanism by which antagonism was being enhanced. First, to understand the effect of the interaction on all members of the co-culture, we performed growth curves of each strain (CP8, CP19 and Bt) in co-culture and compared their individual abundances when grown together to their growth in monoculture using qPCR (Figure S5). Reduced growth in co-culture of all three organisms in comparison to monoculture (Figure S1) classifies this antagonistic interaction as true competition. To better understand how CP8 and CP19 may enhance each other’s antagonistic impact on Bt, we performed exometabolomics analysis on supernatant from this combination. At 24 hours, significantly more lactate was consumed per cell by the CP8/CP19/Bt co-culture than by the CP8/Bt co-culture or CP19/Bt co-culture (p<0.0001) (Figure 4F). Similarly to the single isolate studies, this result once again suggests that lactate utilization may be important for antagonism of Bt in an airway-simulating environment.

To further investigate how the combination of CP8 and CP19 more effectively inhibits the pathogen, we performed a competition assay using the CP8Δsfp mutant in combination with CP19 to understand the degree to which secondary metabolite production was responsible for their combined effect (Figure 4G). When wildtype CP8 was replaced with the CP8Δsfp mutant, there was a significant reduction in Bt inhibitory activity compared to the wildtype CP8/CP19 combination. Together, these findings suggest that both consumption of specific carbon sources and secondary metabolite production are important for activity of the CP8/CP19 combination and likely enable Bt inhibition activity (Figure 4H). While the concept of NIF suggests that coverage of the pathogen niche may be responsible for the observed activity in other combinations, further investigation needs to be done to understand these interactions in more detail.

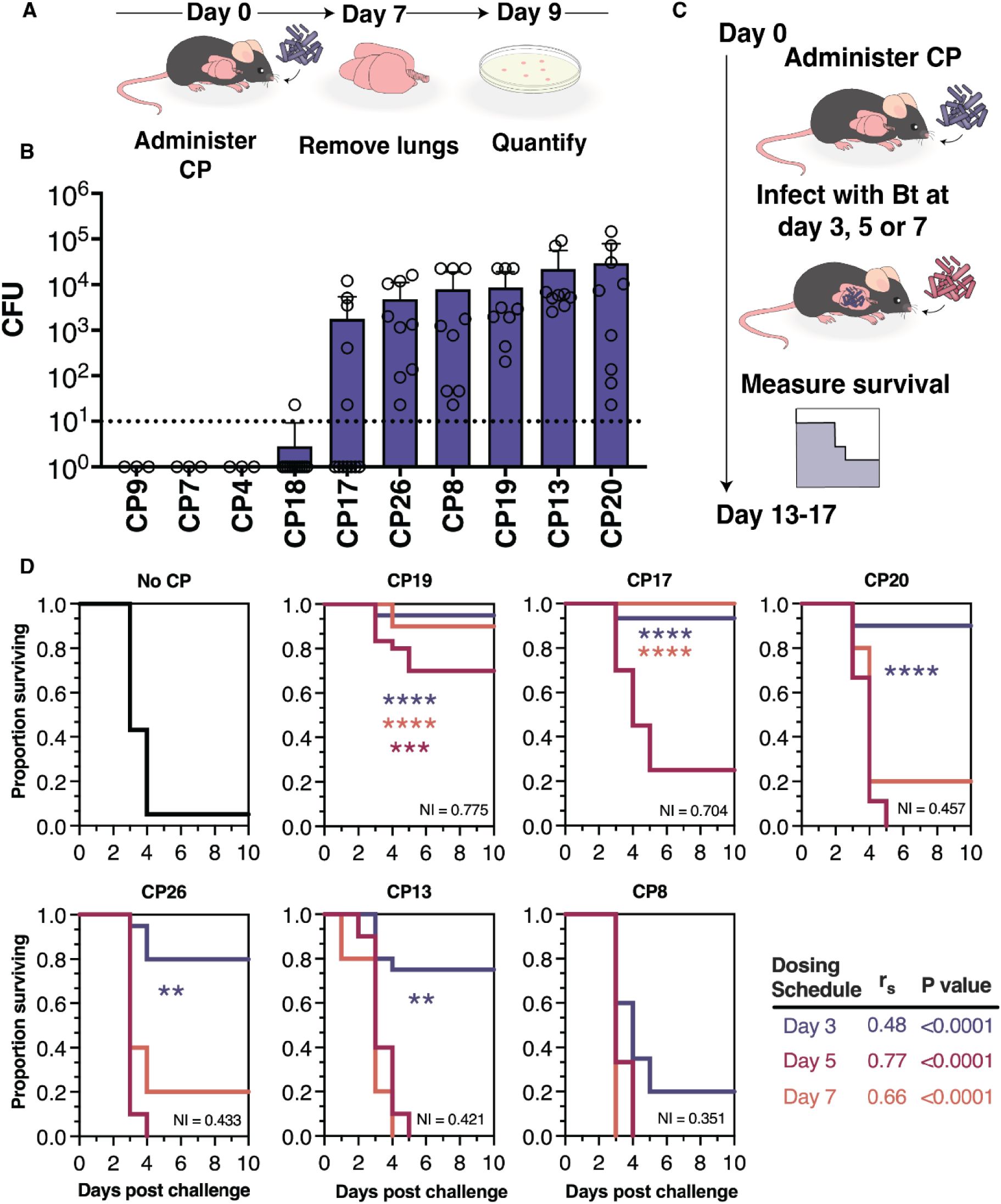

CPs provide protection against infection

Having observed the ability of the CPs to compete with Bt in an in vitro airway-simulating environment, we were encouraged to test their ability to confer protection against respiratory Bt infection in vivo. Firstly, we hypothesized that those CPs which colonized at high density over an extended period of time would provide better protection against Bt infection. To test the airway colonization capabilities of the CPs, we administered each to C57Bl/6j mice at 106 CFU via oropharyngeal aspiration (OPA). After a period of 7 days, the lungs and trachea were assessed for CP load via CFU enumeration (Figure 5A). We found that several CPs were able to colonize the airway for the duration of the 7-day period (Figure 5B). We were particularly interested in those CPs displaying airway colonization (mean airway CFU load of >10 CFU), as these would seem most likely to be capable of protecting against respiratory Bt infection.

CPs colonize the mouse airway, and protect against respiratory Bt infection.

(A) Schematic of colo nization testing for CPs. Each CP (106 CFU) is administered to the lower airway via OPA.. After 7 days, the airway tissues (lungs and trachea) are collected, homogenized, and plated in order to enumerate viable CPs (expressed as CFU per tissue homogenate). (B) Colonization results from airway tissues collected at 7 days following CP administration. The dotted line represents the minimum CFU at which the CP is considered able to colonize in a reliably detectable manner. Data are represented as the mean ± SD. (C) Schematic of the method for survival testing. Each CP (106 CFU) is administered to the lower airway via OPA; and then, at 3, 5, or 7 days post-CP, chal lenged with a normally lethal dose of Bt (3×104 - 5×105 CFU). Survival is measured over the course of 10 days post-Bf. (D) Survival data from mice administered no CP (vehicle control), CPs at 3 days (blue), 5 days (orange), or 7 days (red) prior to Bt challenge. The Niche Index value for each CP is listed in the lower-right corner of its associated graph. Comparison of survival rate with versus without CP treatment was accomplished using the Mantel-Cox test ****P<0.0001, ***P<0.0002, **P<0.01. A summary of the relationship between days surviving and Niche Index value for each dosing schedule is also shown.

We screened both colonizing and non-colonizing CPs for their ability to confer protection in a mouse model of respiratory Bt infection. In these studies, 106 CFU of each of 6 CPs was administered to the airway of C57Bl/6j mice via OPA. Following a period of 3, 5, or 7 days, Bt was administered to the airway and mortality was monitored for 10 days following Bt challenge (Figure 5C). Mice administered no CP prior to Bt challenge showed high mortality, only rarely surviving past day 4 (Figure 5D). In contrast, mice administered certain CPs prior to Bt challenge showed significantly reduced mortality (Figure 5D). Five of the six CPs were protective when administered 3 days prior to Bt challenge; CP17 was protective when administered at 3 or 5 days prior to Bt challenge; and CP19 was protective when administered at 3, 5, or 7 days prior to Bt challenge.

We observed that the most protective probiotics, CP19 and CP17, were predicted to have the highest niche overlap with Bt via their NI values and also showed an ability to inhibit in competition assays (Figure 1C). Furthermore, the CPs that did not inhibit Bt in competition assays yet do robustly colonize (Figure 5B) (i.e. CP13, CP20, and CP26) showed no significant protection when administered 5 or 7 days prior to Bt challenge (Figure 5D). A notable exception to this trend was CP8, which showed inhibition in competition assays as well as robust colonization, but showed no significant protection of mice challenged with Bt. This suggests that niche overlap with the pathogen may be more predictive of the protective capabilities of a probiotic than secondary metabolite production.

Finally, we sought to understand if NICP was related to CP protection efficacy. To test this, we performed a non-parametric spearman rank correlation analysis with the null hypothesis that there existed no relationship between the number of days surviving after pathogen exposure and NICP when CP treatment was performed 3, 5 or 7 days in advance of infection. We found a moderate relationship between survival and NICP when CPs are dosed 3 days prior to infection (r = 0.48, P<0.0001, 95% CI [0.33 to 0.62], N = 115), a very strong relationship when dosed 5 days prior (r = 0.77, P<0.0001, 95% CI [0.60 to 0.88], N = 40) and a strong relationship when dosed 7 days prior (r = 0.66, P<0.0001, 95% CI [0.52 to 0.77], N = 89) (Figure 5D). Interestingly, those CPs (ie. CP13, CP20 and CP26) which do not show inhibition in competition experiments (Figure 1C) conferred a significant survival benefit only when administered 3 days prior to infection. This suggests an alternative mechanism of protection at this timepoint which our model does not capture, such as competition for resources other than carbon (eg. other nutrients) or immune priming. While it appears that NI is a reasonable indicator of the protective effects of a CP in vivo, additional development of this model will need to be done to better capture the host environment, improve prediction and determine the extent to which it can be used to nominate efficacious probiotics in the future.

Discussion

The human respiratory tract microbiome composition has been linked to both respiratory health and the occurrence of respiratory infections54. As a result of this connection, manipulation of the lower airway microbiome is an attractive strategy for anti-infective therapies. Airway microbiome modulation via supplementation with probiotics has previously shown success in preventing infections; however, these studies lack a more broad and systematic analysis which is necessary to learn generalizable principles for the design of efficacious airway probiotics7,8.

In this work, we developed a system that probes interactions between airway-derived candidate probiotics (CPs) and a model respiratory pathogen Burkholderia thailandensis (Bt). From this exploration, we find that consumption of shared resources explains the majority of antagonistic phenotypes between CPs and Bt in vitro. Specifically, consumption of shared carbon sources seems to play an important role in these interactions. As a result, a metric of niche overlap, Niche Index (NI), is correlated with CP inhibitory activity in vitro in most instances. Furthermore, we use these same principles to design combinations of CPs with enhanced antagonism against Bt. We explore the mechanism by which one combination, CP19 and CP8, exploits both metabolic niche exclusion and inhibitory metabolite production to its advantage in competing with Bt. Finally, we find that several CPs are able to re-colonize the mouse airway for at least 7 days, and that two CPs (CP19 and CP17) significantly reduce mortality in mice subjected to otherwise lethal respiratory Bt challenge. While it appears that there is a relationship between the NI and the protective capabilities of a CP, further preclinical experiments will need to be done to determine if NI alone can guide formulation of airway probiotics with clinical applicability. Further, consideration of potential effects from patient genetic background, environment, host immune response, and cross-feeding must also be explored.

The method described here is a step towards a more rapid, inexpensive, and effective means of identifying efficacious probiotics, all factors that have stalled probiotic development previously55. Selection of these probiotics based on their niche-exclusion capabilities, as demonstrated here, also has the potential to enable development of probiotics with better safety profiles. While probiotics with the ability to produce inhibitory small molecules can be identified easily, pathogens can rapidly evolve to evade this form of antagonism. In comparison, probiotics which occupy a niche may leave a pathogen with fewer strategies to evolve resistance, allowing long-term efficacy and more predictable effects on health in clinical applications.

Another great challenge for clinical development of airway probiotics is potency. In order to allow for adequate oxygen exchange in the lungs, alveoli need to remain unobstructed and, thus, colonization of the lung with a large dose of bacteria may result in undesirable outcomes. Therefore, probiotics which require extremely low doses to achieve a protective effect are desirable. Our methodology shows potential for repurposing of organisms that are typically poor performers for use in highly potent multi-organism formulations.

In this work, we found that one way that multi-organism probiotics defend against a pathogen is through consumption of available carbon sources which would otherwise feed the pathogen. In particular, lactate consumption appears to be important for efficacy. Several studies have found that there is increased lactate in the lung during inflammatory exacerbations, which could feed pathogen growth56–58. Interestingly, previous studies have shown that consumption of lactate is important for fitness in the host and pathogenesis for several different bacterial pathogens59–63. Theoretically, if probiotics that preferentially consume lactate can be designed, they may be useful in controlling infections in hosts with inflammatory lung conditions, such as cystic fibrosis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease57,58,64.

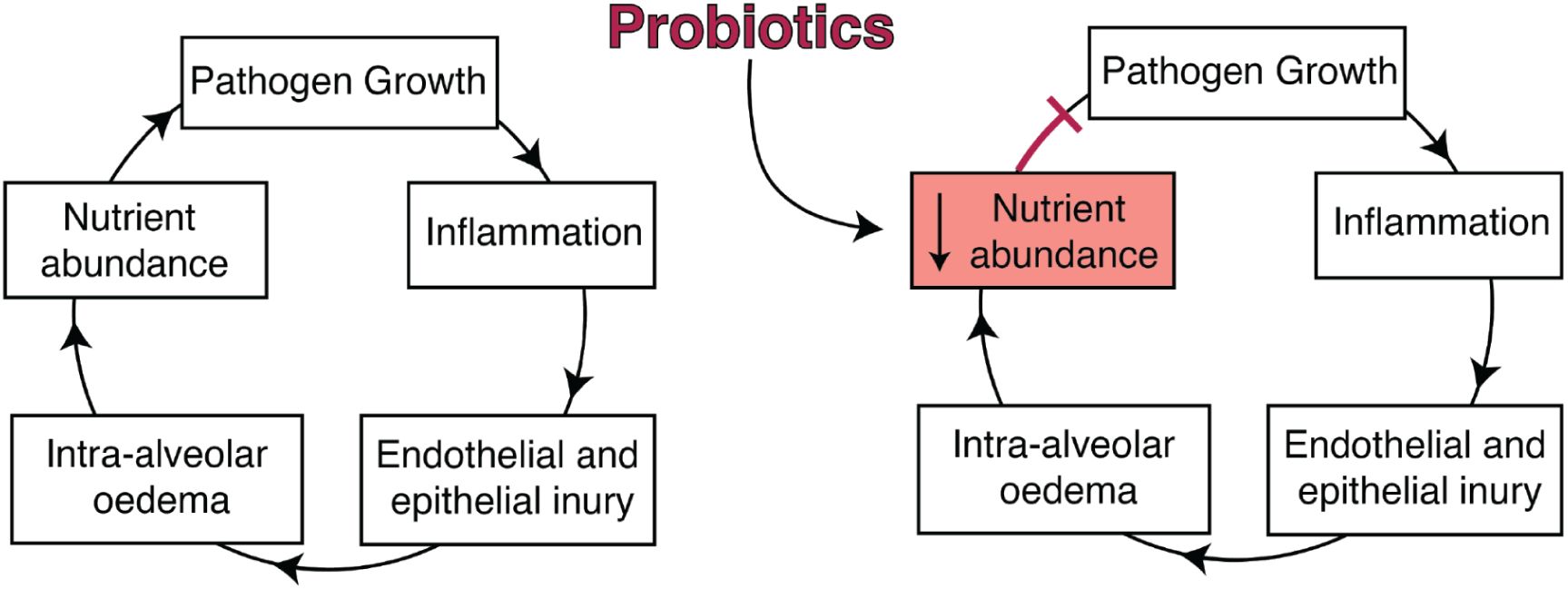

Broadly, we hypothesize that airway probiotics may have functionality by stopping the positive feedback loop of infection. In this model, pathogen infiltration into the lung and growth results in inflammation and cellular injury, causing a leak of nutrient-rich fluids into the alveolar compartment, which further promotes pathogen growth (Figure 6 (left))15. Airway probiotics might stop this feedback loop by depleting nutrient abundance in the local lung environment, thereby limiting pathogen growth (Figure 6 (right))15. Given this model, probiotics which interfere with pathogen metabolism could be forward-designed to work optimally within these environments in order to maximize potency and efficacy.

Proposed mechanism of CP protection.

Left: During lower airway infection, bacterial growth elicits inflammation from the host, with concurrent endothelial and epithelial injury. Intra-alveolar oedema introduces additional nutrients from the blood into the alveoli and lung lumen, enabling further growth of the pathogen. This positive feedback loop results in uncontrolled growth of the pathogen, ultimately facilitating its instantiation. Right: Probiotics delivered directly to the lower airway may limit infection by reducing nutrient abundance after oedema, which prevents further growth of the pathogen and thereby breaks the infection-promoting feedback loop.

The native airway microbiome, and its interactions with host cells and incoming pathogens, is only partially understood, making development of airway probiotics a challenge. As our knowledge grows, health-promoting functionalities could be introduced into the lower respiratory tract, through supplementation with microbiome constituents in unaltered state (as demonstrated here) or with engineered properties, such as novel metabolisms. However, for utility in the clinic, numerous questions will need to be answered about the predictability, long-term safety and reliability of airway probiotics as alternatives or additions to antibiotic therapies. To improve this nomination pipeline further, future models should incorporate elements which have been shown to influence interbacterial antagonism previously such as the rate of consumption of shared resources and and the impact of sudden alterations in resource availability as might occur in acute lung injury. To ensure safety, evolution of the CP in the airway should be monitored over time, and the potential contribution of cross-feeding between CP and pathogen should be investigated. Additionally, future efforts will need to focus on reliable probiotic delivery modalities, formulation stability, and potential for variance in colonization, protection, and immunogenic responses in different hosts and environmental contexts. Work is currently underway to understand the generalizability of the findings here to models of other respiratory diseases, and to evaluate their safety and efficacy for therapeutic applications.

Methods

Isolation and Culture of Bacteria

A Burkholderia thailandensis E264 strain that constitutively expresses GFP was provided by Daniel J. Hassett (University of Cincinnati College of Medicine; Cincinnati, OH)65. The candidate probiotic (CP) isolates were recovered from the lower respiratory tracts of healthy mice using a culturomics approach66. All animal work was conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, protocol 304) and Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC, protocol 2021-010). LLNL is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) International, and is Public Health Service-Assured (PHS assurance A3184-01). Briefly, airway (trachea and lung) tissues were collected from 24 mice (C57Bl/6j, 10-20 weeks), homogenized in 500 uL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and used to inoculate five different solid growth media [tryptic soy (TS); TS + 5% sheep’s blood; M9 minimal salts + 0.2% glucose; brain-heart infusion (BHI); and Luria broth (LB) (Teknova; Hollister, CA)] as well as three different BACTEC blood bottles [Plus Aerobic/F; Plus Anaerobic/F; and Lytic/10 Anaerobic/F (Becton Dickinson; Franklin Lakes, NJ)]. The inoculated solid growth media were incubated at 37C for seven days. The inoculated blood bottles were incubated with shaking (250 rpm) for 1-5 days, and 100 uL aliquots were periodically withdrawn for use in inoculating the five different solid growth media, which were then incubated at 37C for seven days. All colonies detected on the solid growth media were individually transferred to LB agar and, after further incubation at 37C for 1-3 days, streaked to single colonies on fresh LB agar. A representative single colony from each Petri plate was used to inoculate LB liquid and solid media, and these cultures incubated at 37C for 1-3 days for use in preparing frozen glycerol stocks as well as extraction of genomic DNA for sequencing. Sterile tissues (liver and spleen) that were collected from the same mice using a second set of dissection instruments were processed in parallel, in order to recover contaminants of the bacterial isolation procedures [referred to as “background” (B) strains].

Genome Sequencing and Analysis

Extraction of high molecular weight DNA from overnight cultures of CPs was accomplished using the Nanobind CBB kit (PacBio catalog no.102-301-900). Barcoded sequencing libraries were prepared using the SMRTbell prep kit 3.0 (PacBio catalog no.102-141-700) with SMRTbell barcoded adapter 3.0 (PacBio catalog no.102-009-200) and using the Covaris g-TUBE shearing method to generate DNA fragments of 7-12 kb in length. Quantification of DNA concentrations was accomplished using the Qubit fluorometer method. The barcoded libraries were sequenced using a PacBio Sequel IIe system with HiFi workflows; one SMRT Cell 8M was used for run times of 15 hrs.

Raw sequencing reads were assembled using canu v2.2 with its standard options67. Resultant contigs were manually inspected, and BLAST was used to identify and remove duplicate assembled contigs. Phylogenetic placement in the GTDB release 202 system used the ANI-based script speciate.pI68,69. Phylogenomic analysis (Figure 1A) was performed using Species Tree Builder in KBase70. Genome assemblies were submitted to NCBI; assembly IDs are forthcoming.

Comparison of CP versus Airway Microbiome Phylogenetic Assignments

Sequencing reads from 4 independent 16S rRNA profiling investigations of the mouse airway microbiome21–25 were aligned against refseq genome assemblies and placed into taxonomic groups using an established software pipeline called RapTOR. Sequence quality filtering was performed to remove low-quality ends as well as any partial primer sequences, as described previously71,72. The Duskmasker software tool was applied in order to remove low complexity and unidentified reads73. FASTQ sequences with low quality scores were then removed, followed by removal of any host sequences as identified through alignment against the mouse genome sequence (GRCm38) using Bowtie 274. An additional precise alignment with mitochondrial and ribosomal genome sequences was performed to remove any of these host sequences. The remaining non-host (unaligned) sequences were then aligned to the Silva SSU database75 using Bowtie 2 with local alignment settings. The generated “.sam” files were converted to “.taxsum” files using SAMtools76 in a custom Perl script for each sample, producing a table for read abundance at each taxonomy level, with reads aligning equally well to multiple Silva entries placed through application of the lowest common ancestor (LCA) algorithm. Finally, reads mapping to each taxonomic group represented in a given profiling dataset were enumerated; and each group was assigned a rank based on the relative abundance of reads mapping to it (i.e., the prominence with which it was represented in the profiling dataset). This information is summarized for the taxonomic groups to which the CPs [and, for comparison, the B strains (contaminants)] belong (Tables S1-3).

Lung Simulating Medium (LSM) Preparation

LSM was made according to Palmer (2006)17. Adjustments were made to the original formulation to increase sodium and chloride concentrations to more closely match those in healthy lungs. As a result, LSM contains 92mM NaCl, instead of 66.6mM NaCl as in SCFM77. Similarly, glucose concentration was increased to 5.5mM.

Competition Assays

3ml monocultures of individual CPs and Bt were inoculated from frozen glycerol stocks and grown in LSM at 37C with shaking (278rpm) for 24 hours. Cultures were then serially diluted again in LSM at a 1:50 ratio, and grown at 37C with shaking until late log phase, at which point the cultures were centrifuged at 3000g for 10 min and resuspended in fresh LSM. CPs were then diluted according to the ratios being tested, where a 1:1 ratio represented a cell suspension of 3.33×104 CFU/mL, a 0.1 ratio represented 3.33×103 CFU/mL, etc. After dilution, 3.33×104 CFU/ml of Bt was added to each 15ml CP dilution tube as well as to a Bt-only control. The 15ml volume was split into 5 3ml aliquots to make biological replicate assays. All samples were incubated at 37C with shaking for 24 h.

After 24 hours, samples were removed, diluted 1:100-1:100,000 in PBS, and plated onto LB plus carbenicillin (100μg/mL) to select for Bt colonies. Plates were incubated at 37C for 48 h or until colonies became visible, and colony forming units (CFU) were enumerated. Percent Bt growth was calculated by taking the CFU/ml of each replicate culture and dividing by the average of the CFU/ml in the Bt-only control and multiplying by 100. Dose-response curves and analyses were generated using the ECAnything algorithm in Graphpad Prism 10.

Phage Isolation and Plaque Assays

A 3ml culture of each CP was grown at 37C with shaking (278rpm) for 16 h, at which point 2ul of the culture were added to a well of a 2ml deep well plate containing 1ml of LB. These cultures were grown at 30C with shaking (750rpm) for 24 h, at which point each culture was back-diluted 1:70 and grown at 30C with shaking until it reached an OD of 1. To each of these 1ml cultures, 2ul of 3% hydrogen peroxide were added in order to induce phage production. After incubation at 30C with shaking for 16 h, the cultures were centrifuged to pellet cells, and the supernatant was collected and sterilized using a 0.22uM filter. Ammonium sulfate was added to 30% saturation, and precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 16000g for 40 minutes at 4C. The supernatant was decanted, and the phage-containing precipitate was resuspended in 1ml of SM buffer (100mM NaCl, 8mM MgSO4•7H2O, 50mM Tris-Cl, 0.01% gelatin) and stored at 4°C for use in plaque assays.

To perform plaque assays, 3ml of Bt was grown at 37C with shaking (278rpm) for 16 h, at which point it had reached stationary phase. Standard LB agar was prepared in 100×15mm Petri dishes (BD Biosciences) and allowed to cool. To create the soft agar overlay, 200ul of the Bt culture were mixed with 5ml molten LB soft agar (0.5%) and spread over the standard LB agar in each plate. The plates were allowed to cool for 20 min. Phage-containing precipitate was serially diluted 1:10, and 2ul of the solution was pipetted onto the soft agar and allowed to dry for 10 min. The plates were then incubated at 37C for 24 h, and the presence or absence of plaques was observed.

Supernatant Inhibition Experiments

CPs and Bt were grown in LSM monocultures as previously described. The cultures were diluted to 5×105 CFU/ml, and each CP was combined with Bt in co-cultures; additionally, a Bt-only control was generated. The co-cultures were grown at 37C with shaking (278rpm) for ∼72 h, centrifuged to pellet cells, and the supernatants collected and sterilized using a 0.22uM filter. The sterilized supernatant samples were pH adjusted to 7.03. Each supernatant sample was mixed 1:1 with 2X-concentrated LSM, and exponential-phase Bt was added to each mixture at 3.33×104 CFU/mL. Growth curves were performed using a Tecan Spark plate reader, measuring OD600 every 0.25 h during growth at 37C with shaking (240rpm) for 30 h. Fold-change in maximum Bt CFU/ml reached was calculated by dividing the maximum CFU of Bt grown in supernatant from itself divided by the maximum CFU of Bt grown in supernatant from each CP co-culture.

Knockout of sfp in CP8

The CP8Δsfp mutant was generated using a double-crossover homologous recombination method described previously78. Briefly, homologous arms were amplified up- and down-stream of the sfp gene using PCR, and the amplicon was cloned into the T2(2)-ori plasmid in addition to the oriT/traJ region which facilitates conjugative transfer using Golden Gate assembly. The resulting plasmid was introduced into CP8 using an established method for conjugation in Bacillus79. The transconjugants were plated onto LB supplemented with kanamycin (20 μg/mL) and polymyxin B (5 μg/mL) to select for plasmid-bearing CP8. Colonies recovered from the selection plates were used to inoculate 3ml LB plus kanamycin (20 μg/mL), and the resulting cultures were grown at 37C with shaking (278rpm) for 16 h. 0.05 ml of each culture were then spread on an LB plus kanamycin (20 μg/mL) plate that was incubated at 45C for 16 h in order to induce the first crossover event. A single colony positive for the first crossover event by PCR was recovered from each plate and passaged 6 times in LB liquid culture. Liquid cultures were streaked onto 10 LB agar plates to generate single colonies. Replica plating of 96 colonies was performed to check for loss of kanamycin resistance, and PCR was used to screen for colonies in which sfp was absent. Resulting fragments and the 16S region were sequenced to confirm deletion and strain identity.

Growth Curves of CP8 and the CP8Δsfp Mutant

CP8 and the CP8Δsfp mutant were streaked on LB agar and incubated at 37C for 16 h. Single colonies were used to inoculate 3ml LB cultures in 14ml plastic tubes, and the cultures incubated at 37C with shaking (278rpm) until they reached early stationary phase. The cultures were then back-diluted to an OD of 0.1 in LB, and 100ul of the cell suspension were added to each well of a 96-well plate, generating 4 replicate assays per condition. Growth curves were performed using a Tecan Spark plate reader, measuring OD600 every 0.16 h during growth at 37C with shaking (240rpm) for 20 h.

Agar Diffusion Assays

Overnight cultures of Bt and CP8 were made in LSM as previously described. Bt was diluted to OD 0.5 and streaked onto LSM agar using a sterile cotton swab. Plates were briefly allowed to dry and 2ul spots of CP8 overnight culture were added. Plates were incubated at 37C and checked for the appearance of a zone of inhibition after 48 h.

Carbon Source Screening

Overnight cultures of CPs and Bt in LSM were generated as previously described. Cultures were centrifuged and the pelleted bacteria washed twice with 2x LSM with carbon sources removed. The bacteria were then diluted to an OD of 0.04, and 20 ul were added to each well of a 384-well plate in which individual carbon source from LSM were deposited to produce a final concentration of 10mM. Initial OD600 readings were taken using a plate reader, and then the plates were incubated at 30C with shaking (800rpm) for 3 days before a final OD600 reading was taken. Each CP or Bt was considered able to utilize a given carbon source if the final OD600 reading was greater than that of the blank plus 2 standard deviations.

Exometabolomics

Overnight cultures of CP7, CP8, CP19 and Bt were generated as previously described. The cultures were back-diluted 1:50 and then grown at 37C with shaking (278rpm) to late log phase. 3ml co-cultures were made in LSM combining Bt at 3.33×104 CFU/ml with the relevant CP at its IC90. The co-cultures were incubated at 37C with shaking, and 1ml samples were collected at 24 h and 36 h. For collection, each sample was centrifuged at 3000rcf for 10 min, and the . supernatant was removed and syringe filtered to remove residual cellular material. Samples were analyzed via GC-TOF by the West Coast Metabolomics Center (Davis, CA). Data were SERRF normalized to remove batch effects, then normalized to the amount injected. Metabolite concentrations were normalized to a media-only control. For analysis, concentrations of each metabolite were converted to metabolite-contributed electrons using the oxidation-reduction half reaction for each metabolite analyzed. For carbon subset analysis, total electrons from lactate, proline, and aspartic acid in the co-culture supernatant at 24 hours were added. Electron concentrations below 0 indicate that a given metabolite is more abundant in co-culture than the media control.

Pairwise Combination Competition Assays

Pairwise combination competition assays were performed as described above (“Competition Assays”) with the following adjustment. After resuspension in fresh media, the two CPs of interest were mixed together at a 1:1 ratio to generate the desired final CFU/ml (eg. for a 1:1 ratio with Bt, the two CPs were combined to generate a final concentration of 3.33×104 CFU/ml). Subsequent dilutions were made and carried out as previously described.

Quantification of CP8, CP19 and Bt Growth in Co-Culture

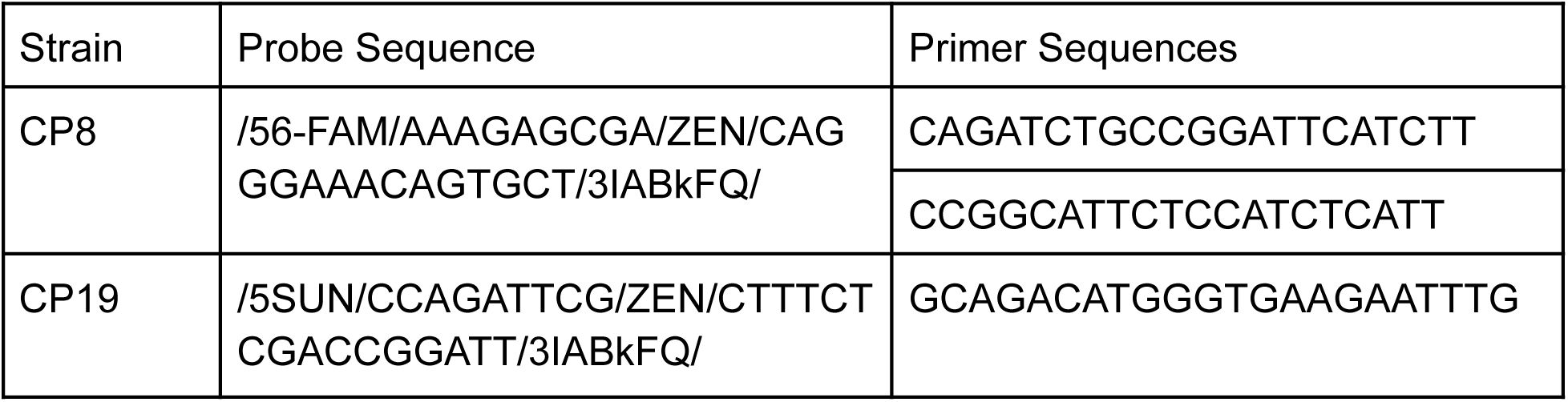

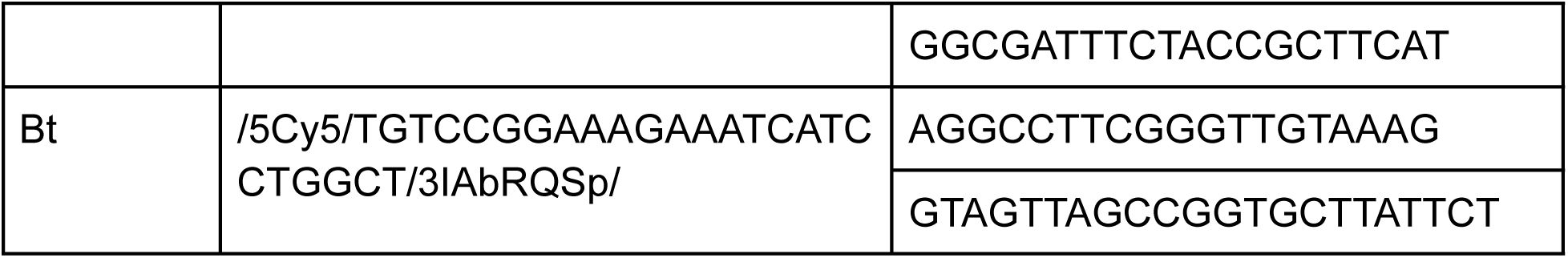

qPCR primers and probes for the 16S rRNA region for CP8, CP19 and Bt were purchased from IDT with the following sequences:

To generate standard curves, overnight cultures of CP8, CP19 and Bt were made as previously described in LB. The following day, cultures were backdiluted 1:250 in LB and 1ml of each culture was collected at 11 timepoints. Optical density at each timepoint was measured (OD600 values ranged from 0.05 to 1.033) and cells were pelleted by centrifugation. Genome preparations were done on each pellet using the QIAgen DNeasy Powersoil kit (cat#47014). Concentrations of genomic DNA were quantified using the Qubit dsDNA Quantification Assay Kit (cat#Q32854). A 1:5 dilution of each sample was made to adjust DNA concentration to 3pg-100ng. PrimeTime Gene Expression Master Mix (cat#1055772) was used to run the qPCR reactions in triplicate, with 2ul of diluted genome preparation per well. Samples were analyzed using the BioRad CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR detection system, with annealing at 60C. To create the standard curve, OD values were plotted against Cq values and a line was fit to the points.

To generate the growth curve, three biological replicates of CP8, CP19 and Bt were co-cultured in LSM at 37C and 278rpm for 36 hours, with 1ml collections made every hour between 4-30 hours post-inoculation and an additional collection made at 36 hours. Optical density measurements, DNA extraction and qPCR reaction preparation were performed as previously described. Samples were run in duplicate using the previously established conditions. Measured Cq values from the co-culture samples were converted to OD600 values for each organism using the previously generated standard curve.

Animal Models

These studies were carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the National Institute of Health. All efforts were made to minimize suffering of animals. All animals were housed in ABSL2 conditions in an AAALAC-accredited and PHS-assured facility, and the protocol was approved by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), which includes ethics in evaluation of protocols. Barrier-housed, specific pathogen-free 6 week old C57Bl/6j mice were acclimated prior to experiments. CP, Bt, and animal use were also approved by the Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC).

Colonization Studies

Each CP was grown in monoculture in LB at 37C with shaking (250 rpm) for 16 h, recovered through centrifugation, resuspended in PBS, and diluted to an OD600 corresponding to 3.3×107 CFU/mL (based on prior determination of OD600-to-CFU plating efficiency measurements). 30 ul of this dosing material (corresponding to 106 CFU) were administered to the airway (via OPA) of each mouse. After 7 days, the trachea and lungs were collected and homogenized in PBS; dilutions (in PBS) were plated on LB agar; and, after 1-5 days at 37C, the CFU enumerated in order to assess CP load in the airway tissues.

Survival Studies

CP dosing material was generated and administered to mice as described above. After 3, 5 or 7 days, the mice were similarly administered (via OPA) 3×104 - 5×105 CFU of Bt. Weight, morbidity, and mortality were monitored for 10 days following Bt challenge; mice displaying ≥20% loss of body weight were euthanized.

Statistical analyses

Ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, ROC curve analyses, Mantel-Cox survival analyses, and all plotting of data to generate graphs, was completed using Graphpad Prism 10.

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Sander (UCB) and K. Vyas (CMS) for helpful discussion; D. Sivanandan (UCB) for assistance with experiments; and M. Hirakawa (SNL) for critical review of the manuscript. We thank the West Coast Metabolomics Center for exometabolomics services. Sandia National Laboratories is a multimission laboratory managed and operated by National Technology & Engineering Solutions of Sandia, LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Honeywell International Inc., for the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration under contract DE-NA0003525.

Additional information

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.E.H., S.S.B. and A.P.A.; Methodology, A.M.P., N.M.C., K.E.H. and H.K.K; Investigation, A.M.P, N.M.C., S.S.B., K.E.H. and H.K.K.; Formal analyses - C.M.M., K.P.W., K.P., S.S.B., A.S., and K.E.H.; Writing – Original Draft, K.E.H.; Writing - Review & Editing, all authors; Funding acquisition, S.S.B. and A.P.A; Supervision, S.S.B. and A.P.A.

Additional files

References

- 1.Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and timeScience 326:1694–1697Google Scholar

- 2.The Human Respiratory System and its Microbiome at a GlimpseBiology 9Google Scholar

- 3.The microbiota of the respiratory tract: gatekeeper to respiratory healthNat. Rev. Microbiol 15:259–270Google Scholar

- 4.A prevalent and culturable microbiota links ecological balance to clinical stability of the human lung after transplantationNat. Commun 12:2126Google Scholar

- 5.Interactions between the microbiota and pathogenic bacteria in the gutNature 535:85–93Google Scholar

- 6.Control of pathogens and pathobionts by the gut microbiotaNat. Immunol 14:685–690Google Scholar

- 7.Lactobacilli intra-tracheal administration protects from Pseudomonas aeruginosa pulmonary infection in mice - a proof of conceptBenef Microbes 10:893–900Google Scholar

- 8.Respiratory tissue-associated commensal bacteria offer therapeutic potential against pneumococcal colonizationeLife Google Scholar

- 9.Burkholderia cepacia is associated with pulmonary hypertension and increased mortality among cystic fibrosis patientsJ. Clin. Microbiol 42:5537–5541Google Scholar

- 10.Taxonomy and identification of the Burkholderia cepacia complexJ. Clin. Microbiol 39:3427–3436Google Scholar

- 11.Genomic patterns of pathogen evolution revealed by comparison of Burkholderia pseudomallei, the causative agent of melioidosis, to avirulent Burkholderia thailandensisBMC Microbiol 6:46Google Scholar

- 12.Burkholderia thailandensis sp. nov., a Burkholderia pseudomallei-like speciesInt. J. Syst. Bacteriol 48:317–320Google Scholar

- 13.Bacterial genome adaptation to niches: divergence of the potential virulence genes in three Burkholderia species of different survival strategiesBMC Genomics 6:174Google Scholar

- 14.Surfactant alterations in severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and cardiogenic lung edemaAm. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 153:176–184Google Scholar

- 15.Towards an ecology of the lung: new conceptual models of pulmonary microbiology and pneumonia pathogenesisLancet Respir Med 2:238–246Google Scholar

- 16.The Lung Microbiome: New Principles for Respiratory Bacteriology in Health and DiseasePLoS Pathog 11:e1004923Google Scholar

- 17.Nutritional cues control Pseudomonas aeruginosa multicellular behavior in cystic fibrosis sputumJ. Bacteriol 189:8079–8087Google Scholar

- 18.Pseudomonas aeruginosa breaches respiratory epithelia through goblet cell invasion in a microtissue modelNat. Microbiol 9:1725–1737Google Scholar

- 19.Secondary metabolite profiling of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates reveals rare genomic traitsmSystems 9:e0033924Google Scholar

- 20.Untargeted metabolomics reveals species-specific metabolite production and shared nutrient consumption by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureusmSystems 6:e0048021Google Scholar

- 21.The murine lung microbiome in relation to the intestinal and vaginal bacterial communitiesBMC Microbiol 13:303Google Scholar

- 22.Three distinct pneumotypes characterize the microbiome of the lung in BALB/cJ micePLoS One 12:e0180561Google Scholar

- 23.Development of a stable lung microbiome in healthy neonatal miceMicrob Ecol 75:529–542Google Scholar

- 24.The lung Microbiota of healthy mice are highly variable, cluster by environment, and reflect variation in baseline lung innate immunityAm. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 198:497–508Google Scholar

- 25.Lung Microbiota contribute to pulmonary inflammation and disease progression in pulmonary fibrosisAm. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 199:1127–1138Google Scholar

- 26.Competition for space during bacterial colonization of a surfaceJ. R. Soc. Interface 12:0608Google Scholar

- 27.Density of founder cells affects spatial pattern formation and cooperation in Bacillus subtilis biofilmsISME J 8:2069–2079Google Scholar

- 28.Dynamic modulation of the gut Microbiota and metabolome by bacteriophages in a mouse modelCell Host Microbe 25:803–814Google Scholar

- 29.Effect of acute predation with bacteriophage on intermicrobial aggression by Pseudomonas aeruginosaPLoS One 12:e0179659Google Scholar

- 30.Characterization of the Burkholderia thailandensis SOS response by using whole-transcriptome shotgun sequencingAppl Environ Microbiol 79:5830–5843Google Scholar

- 31.Genetic and phenotypic diversity in Burkholderia: contributions by prophage and phage-like elementsBMC Microbiol 10:202Google Scholar

- 32.Filamentous phages prevalent in Pseudoalteromonas spp. confer properties advantageous to host survival in Arctic sea iceISME J 9:871–881Google Scholar

- 33.Systematic discovery of pseudomonad genetic factors involved in sensitivity to tailocinsISME J 15:2289–2305Google Scholar

- 34.antiSMASH 7.0: new and improved predictions for detection, regulation, chemical structures and visualisationNucleic Acids Res 51:W46–W50Google Scholar

- 35.Whole-Cell MALDI-ToF MS Coupled with Untargeted Metabolomics Facilitates Investigations of Microbial Chemical InteractionsChembiochem 24:e202200802Google Scholar

- 36.Isolation and characterization of sfp: a gene that functions in the production of the lipopeptide biosurfactant, surfactin, in Bacillus subtilisMol. Gen. Genet 232:313–321Google Scholar

- 37.Characterization of Sfp, a Bacillus subtilis phosphopantetheinyl transferase for peptidyl carrier protein domains in peptide synthetasesBiochemistry 37:1585–1595Google Scholar

- 38.More than anticipated - production of antibiotics and other secondary metabolites by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol 16:14–24Google Scholar

- 39.Genetic analysis of the cold-sensitive growth phenotype of Burkholderia pseudomallei/thailandensis bacteriophage AMP1Sci. Rep 12:4288Google Scholar

- 40.Resource competition predicts assembly of gut bacterial communities in vitroNat. Microbiol 9:1036–1048Google Scholar

- 41.Metabolic modeling of species interaction in the human microbiome elucidates community-level assembly rulesProc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110:12804–12809Google Scholar

- 42.Deciphering microbial interactions in synthetic human gut microbiome communitiesMol. Syst. Biol 14:e8157Google Scholar

- 43.Specificity of polysaccharide use in intestinal bacteroides species determines diet-induced microbiota alterationsCell 141:1241–1252Google Scholar

- 44.Inferring metabolic mechanisms of interaction within a defined gut MicrobiotaCell Syst 7:245–257Google Scholar

- 45.On the proportions of organic derivatives in sea water and their relation to the composition of planktonJames Johnstone Memorial :176–194Google Scholar

- 46.A Stoichioproteomic Analysis of Samples from the Human Microbiome ProjectFront. Microbiol 8:1119Google Scholar

- 47.Are pathogenic bacteria just looking for food? Metabolism and microbial pathogenesisTrends Microbiol 19:341–348Google Scholar

- 48.The measurement of niche overlap and some relativesEcology 59:67–77Google Scholar

- 49.Likelihood measures of niche breadth and overlapEcology 60:703–710Google Scholar

- 50.Niche breadth, resource availability, and inferenceEcology 63:1675Google Scholar

- 51.The peril of proportions: robust niche indices for categorical dataMethods Ecol. Evol 8:223–231Google Scholar

- 52.Dose-response curve slope helps predict therapeutic potency and breadth of HIV broadly neutralizing antibodiesNat. Commun 6:8443Google Scholar

- 53.Pharmacodynamic functions: a multiparameter approach to the design of antibiotic treatment regimensAntimicrob Agents Chemother 48:3670–3676Google Scholar

- 54.The Lung Microbiome during Health and DiseaseInt. J. Mol. Sci 22Google Scholar

- 55.How to select a probiotic? A review and update of methods and criteriaBiotechnol Adv 36:2060–2076Google Scholar

- 56.Lactate production by the lungs in acute lung injuryAm. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 156:1099–1104Google Scholar

- 57.Lactate in cystic fibrosis sputumJ. Cyst. Fibros 10:37–44Google Scholar

- 58.Lactic acid is elevated in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and induces myofibroblast differentiation via pH-dependent activation of transforming growth factor-βAm. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 186:740–751Google Scholar

- 59.Dysbiosis-associated change in host metabolism generates lactate to support Salmonella growthCell Host Microbe 23:54–64Google Scholar

- 60.In vivo proteome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in airways of cystic fibrosis patientsJ. Proteome Res 18:2601–2612Google Scholar

- 61.Neisseria meningitidis lactate permease is required for nasopharyngeal colonizationInfect. Immun 73:5762–5766Google Scholar

- 62.Lactate utilization is regulated by the FadR-type regulator LldR in Pseudomonas aeruginosaJ. Bacteriol 194:2687–2692Google Scholar

- 63.Transcriptional regulation of a gonococcal gene encoding a virulence factor (L-lactate permease)PLoS Pathog 15:e1008233Google Scholar

- 64.Bronchoalveolar pH and inflammatory biomarkers in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseaseJ. Int. Med. Res 47:791–802Google Scholar

- 65.Construction and characterization of stable, constitutively expressed, chromosomal green and red fluorescent transcriptional fusions in the select agents, Bacillus anthracis, Yersinia pestis, Burkholderia mallei, and Burkholderia pseudomalleiMicrobiologyopen 3:610–629Google Scholar

- 66.Microbial culturomics: paradigm shift in the human gut microbiome studyClin. Microbiol. Infect 18:1185–1193Google Scholar

- 67.Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separationGenome Res 27:722–736Google Scholar

- 68.GTDB: an ongoing census of bacterial and archaeal diversity through a phylogenetically consistent, rank normalized and complete genome-based taxonomyNucleic Acids Res 50:D785–D794Google Scholar

- 69.Improved Mobilome Delineation in Fragmented GenomesFront Bioinform 2:866850Google Scholar

- 70.KBase: The United States Department of Energy Systems Biology KnowledgebaseNat. Biotechnol 36:566–569Google Scholar

- 71.cDNA normalization by hydroxyapatite chromatography to enrich transcriptome diversity in RNA-seq applicationsBiotechniques 53:373–380Google Scholar

- 72.Transcriptomic analysis of Yersinia enterocolitica biovar 1B infecting Murine macrophages reveals new mechanisms of extracellular and intracellular survivalInfect. Immun 83:2672–2685Google Scholar

- 73.A fast and symmetric DUST implementation to mask low-complexity DNA sequencesJ. Comput. Biol 13:1028–1040Google Scholar

- 74.Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2Nat. Methods 9:357–359Google Scholar

- 75.The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based toolsNucleic Acids Res 41:D590–6Google Scholar

- 76.Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtoolsGigascience 10Google Scholar

- 77.Submucosal gland secretions in airways from cystic fibrosis patients have normal [Na+] and pH but elevated viscosityProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98:8119–8123Google Scholar

- 78.Deletion of meso-2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase gene budC for enhanced D-2,3-butanediol production in Bacillus licheniformisBiotechnol Biofuels 7:16Google Scholar

- 79.Transmating: conjugative transfer of a new broad host range expression vector to various Bacillus species using a single protocolBMC Microbiol 18:56Google Scholar

Article and author information

Author information

Version history

- Preprint posted:

- Sent for peer review:

- Reviewed Preprint version 1:

Cite all versions

You can cite all versions using the DOI https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.108304. This DOI represents all versions, and will always resolve to the latest one.

Copyright

This is an open-access article, free of all copyright, and may be freely reproduced, distributed, transmitted, modified, built upon, or otherwise used by anyone for any lawful purpose. The work is made available under the Creative Commons CC0 public domain dedication.

Metrics

- views

- 312

- downloads

- 13

- citations

- 0

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.