Peer review process

Revised: This Reviewed Preprint has been revised by the authors in response to the previous round of peer review; the eLife assessment and the public reviews have been updated where necessary by the editors and peer reviewers.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorMohan BalasubramanianUniversity of Warwick, Coventry, United Kingdom

- Senior EditorQiang CuiBoston University, Boston, United States of America

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

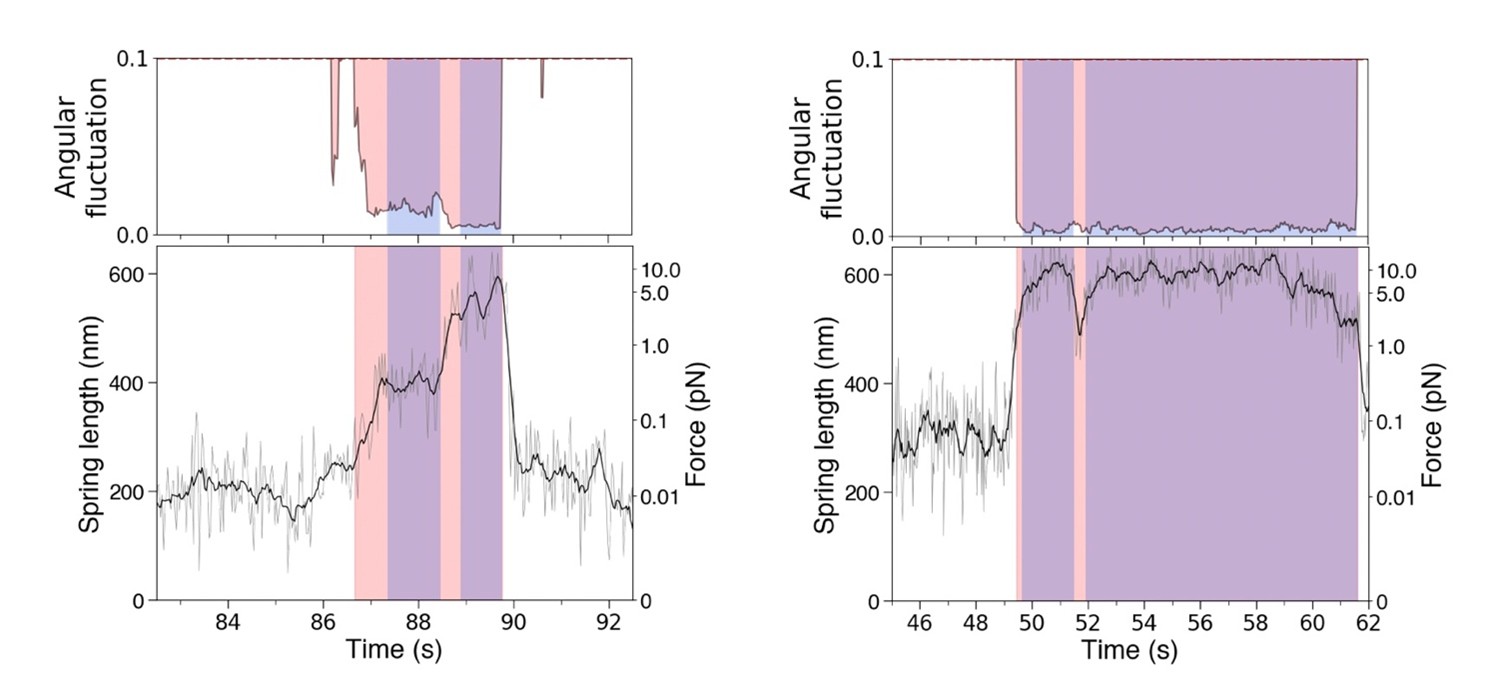

This study uses a novel DNA origami nanospring to measure the stall force and other mechanical parameters of the kinesin-3 family member, KIF1A, using light microscopy. The key is to use SNAP tags to tether a defined nanospring between a motor-dead mutant of KIF5B and the KIF1A to be integrated. The mutant KIF5B binds tightly to a subunit of the microtubule without stepping, thus creating resistance to the processive advancement of the active KIF1A. The nanospring is conjugated with 124 Cy3 dyes, which allows it to be imaged by fluorescence microscopy. Acoustic force spectroscopy was used to measure the relationship between the extension of the NS and force as a calibration. Two different fitting methods are described to measure the length of the extension of the NS from its initial diffraction-limited spot. By measuring the extension of the NS during an experiment, the authors can determine the stall force. The attachment duration of the active motor is measured from the suppression of lateral movement that occurs when the KIF1A is attached and moving. There are numerous advantages of this technology for the study of single molecules of kinesin over previous studies using optical tweezers. First, it can be done using simple fluorescence microscopy and does not require the level of sophistication and expense needed to construct an optical tweezer apparatus. Second, the force that is experienced by the moving KIF1A is parallel to the plane of the microtubule. This regime can be achieved using a dual beam optical tweezer set-up, but in the more commonly used single-beam set-up, much of the force experienced by the kinesin is perpendicular to the microtubule. Recent studies have shown markedly different mechanical behaviors of kinesin when interrogated by the two different optical tweezer configurations. The data in the current manuscript are consistent with those obtained using the dual-beam optical tweezer set-up. In addition, the authors study the mechanical behavior of several mutants of KIF1A that are associated with KIF1A-associated neurological disorder (KAND).

Strengths:

The technique should be cheaper and less technically challenging than optical tweezer microscopy to measure the mechanical parameters of molecular motors. The method is described in sufficient detail to allow its use in other labs. It should have a higher throughput than other methods.

Weaknesses:

The experimenter does not get a "real-time" view of the data as it is collected, which you get from the screen of an optical tweezer set-up. Rather, you have to put the data through the fitting routines to determine the length of the nanospring in order to generate the graphs of extension (force) vs time. No attempts were made to analyze the periods where the motor is actually moving to determine step-size or force-velocity relationships.

Comments on revisions:

I am satisfied with the revision made by the authors in response to my first round of criticisms.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

This work is important in my view because it complements other single-molecule mechanics approaches, in particular optical trapping, which inevitably exerts off-axis loads. The nanospring method has its own weaknesses (individual steps cannot be seen), but it brings new clarity to our picture of KIF1A and will influence future thinking on the kinesins-3 and on kinesins in general.

Strengths:

By tethering single copies of the kinesin-3 dimer under test via a DNA nanospring to a strong binding mutant dimer of kinesin-1, the forces developed and experienced by the motor are constrained into a single axis, parallel to the microtubule axis. The method is imaging-based which should improve accessibility. In principle, at least, several single-motor molecules can be simultaneously tested. The arrangement ensures that only single molecules can contribute. Controls establish that the DNA nanospring is not itself interacting appreciably with the microtubule. Forces are convincingly calibrated and reading the length of the nanospring by fitting to the oblate fluorescent spot is carefully validated. The excursions of the wild type KIF1A leucine zipper-stabilised dimer are compared with those of neuropathic KIF1A mutants. These mutants can walk to a stall plateau, but the force is much reduced. The forces from mutant/WT heterodimers are also reduced.

Weaknesses:

The tethered nanospring method has some weaknesses; it only allows the stall force to be measured in the case that a stall plateau is achieved, and the thermal noise means that individual steps are not apparent. The nanospring does not behave like a Hookean spring - instead linearly increasing force is reported by exponentially smaller extensions of the nanospring under tension. The estimated stall force for Kif1A (3.8 pN) is in line with measurements made using 3 bead optical trapping, but those earlier measurements were not of a stall plateau, but rather of limiting termination (detachment) force, without a stall plateau.

Comments on revisions:

The authors have successfully addressed my previous criticisms.