Author response:

eLife Assessment

This useful study examines whether the sugar trehalose, coordinates energy supply with the gene programs that build muscle in the cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera). The evidence for this currently is incomplete. The central claim - that trehalose specifically regulates an E2F/Dp-driven myogenic program - is not supported by the specificity of the data: perturbations and sequencing are systemic, alternative explanations such as general energy or amino-acid scarcity remain plausible, and mechanistic anchors are also limited. The work will interest researchers in insect metabolism and development; focused, tissue-resolved measurements together with stronger mechanistic controls would substantially strengthen the conclusions.

We thank the reviewer for the thoughtful and constructive evaluation of our work and for recognizing its potential relevance to researchers working on insect metabolism and development. We fully agree that our current evidence is preliminary and that the mechanistic link between trehalose and the E2F/Dp‑driven myogenic program needs to be strengthened.

Our intention was to present trehalose-E2F/Dp coupling as a working model emerging from our data, rather than as a fully established pathway. We agree that systemic manipulations of trehalose and whole‑larval RNA‑seq cannot fully differentiate global metabolic stress from specific effects on myogenic programs. In the revision, we plan to include additional metabolic readouts (e.g., ATP/AMP ratio, key amino acids where available) to better discuss the overall energetic and nutritional state. We will reanalyze our RNA‑seq data to more clearly distinguish broad stress/metabolic signatures from cell‑cycle/myogenic signatures. Furthermore, we will reframe our discussion to explicitly state that we cannot completely rule out a contribution of general energy or amino‑acid scarcity at this stage.

We acknowledge that, with our current experiments, the specificity for an E2F/Dp‑driven program is inferred mainly from enrichment of E2F targets among differentially expressed genes, and expression changes in canonical E2F partners and downstream cell‑cycle/myogenic regulators. To address this more rigorously, we are performing targeted qRT-PCR for a panel of well‑characterized E2F/Dp target genes and myogenic markers in larval muscle versus non‑muscle tissues, following trehalose perturbation. Where technically feasible, testing whether partial knockdown of HaE2F or HaDp modifies the effect of trehalose manipulation on selected myogenic markers. These data, even if limited, will help to provide a more direct functional link, and we will include them in the manuscript if completed in time. In parallel, we will soften statements that imply a fully established, trehalose‑specific regulation of E2F/Dp and instead present this as a strong candidate pathway suggested by the current data.

We fully agree that tissue‑resolved analyses are essential to move from systemic correlations to causality in muscle. We are in the process of standardizing larval muscle dissections and isolating thoracic/abdominal body wall muscle for trehalose, glycogen, and expression assays. Comparing expression of key metabolic and myogenic genes in muscle versus fat body and midgut, under trehalose manipulation. These tissue‑resolved data will directly address whether the transcriptional changes we report are preferentially localized to muscle.

We are grateful for the reviewer’s critical but encouraging comments. We will moderate our central claims, also explicitly consider and discuss alternative explanations. Further, we will add tissue‑resolved and more focused mechanistic data as far as possible within the current revision. We believe these changes will substantially strengthen the manuscript and better align our conclusions with the evidence we presently have.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

In this work by Mohite et al., they have used transcriptomic and metabolic profiling of H. armigera, muscle development, and S. frugiperda to link energy trehalose metabolism and muscle development. They further used several different bioinformatics tools for network analysis to converge upon transcriptional control as a potential mechanism of metabolite-regulated transcriptional programming for muscle development. The authors have also done rescue experiments where trehalose was provided externally by feeding, which rescues the phenotype. Though the study is exciting, there are several concerns and gaps that lead to the current results as purely speculative. It is difficult to perform any genetic experiments in non-model insects; the authors seem to suggest a similar mechanism could also be applicable in systems like Drosophila; it might be possible to perform experiments to fill some missing mechanistic details.

A few specific comments below:

The authors used N-(phenylthio) phthalimide (NPP), a trehalose-6-phosphate phosphatase (TPP) inhibitor. They also find several genes, including enzymes of trehalose metabolism, that change. Further, several myogenic genes are downregulated in bulk RNA sequencing. The major caveat of this experiment is that the NPP treatment leads to reduced muscle development, and so the proportion of the samples from the muscles in bulk RNA sequencing will be relatively lower, which might have led to the results. So, a confirmatory experiment has to be performed where the muscle tissues are dissected and sequenced, or some of the interesting targets could be validated by qRT-PCR. Further to overcome the off-target effects of NPP, trehalose rescue experiments could be useful.

Thank you for this valuable comment. We will validate the gene expression data using qRT-PCR on muscle tissue samples from both treated and control groups. This will help determine whether the gene expression patterns observed in the RNA-seq data are muscle-specific or systemic.

Even the reduction in the levels of ADP, NAD, NADH, and NMN, all of which are essential for efficient energy production and utilization, could be due to the loss of muscles, which perform predominantly metabolic functions due to their mitochondria-rich environment. So it becomes difficult to judge if the levels of these energy molecules' reduction are due to a cause or effect.

We thank the reviewer for this thoughtful comment and agree that reduced levels of ADP, NAD, NADH, and NMN could arise either from a disturbance of energy metabolism or from loss of mitochondria‑rich muscles. Our current data cannot fully separate these two possibilities. Still, several studies support the interpretation that perturbing trehalose metabolism causes a primary systemic energy deficit that is coupled to mitochondrial function, not merely a passive consequence of tissue loss.

For example:

(1) Our previous study in H. armigera showed that chemical inhibition of trehalose synthesis results in depletion of trehalose, glucose, glucose‑6‑phosphate, and suppression of the TCA cycle, indicating reduced energy levels and dysregulated fatty‑acid oxidation (Tellis et al., 2023).

(2) Chang et al. (2022) showed that trehalose catabolism and mitochondrial ATP production are mechanistically linked. HaTreh1 localizes to mitochondria and physically interacts with ATP synthase subunit α. 20‑hydroxyecdysone increases HaTreh1 expression, enhances its binding to ATP synthase, and elevates ATP content, while knockdown of HaTreh1 or HaATPs‑α reduces ATP levels.

(3) Similarly, our previous study inhibition of Treh activity in H. armigera generates an “energy‑deficient condition” characterized by deregulation of carbohydrate, protein, fatty‑acid, and mitochondria‑related pathways, and a concomitant reduction in key energy metabolites (Tellis et al., 2024).

(4) The starvation study in H. armigera has shown that reduced hemolymph trehalose is associated with respiratory depression and large‑scale reprogramming of glycolysis and fatty‑acid metabolism (Jiang et al., 2019).

These findings support a direct coupling between trehalose availability and systemic energy/redox state. Therefore, the coordinated decrease in ADP, NAD, NADH, and NMN following TPS/TPP silencing is consistent with a primary disturbance of systemic energy and mitochondrial metabolism rather than exclusively a secondary consequence of muscle loss. We agree, however, that the present whole‑larva metabolite measurements do not allow a quantitative partitioning between changes due to altered muscle mass and those due to intrinsic metabolic impairment at the cellular level. Thus, tissue-specific quantification of these metabolites would allow us to directly test whether altered energy metabolites are a cause or consequence of muscle loss.

References:

(1) Tellis, M. B., Mohite, S. D., Nair, V. S., Chaudhari, B. Y., Ahmed, S., Kotkar, H. M., & Joshi, R. S. (2024). Inhibition of Trehalose Synthesis in Lepidoptera Reduces Larval Fitness. Advanced Biology, 8(2), 2300404.

(2) Chang, Y., Zhang, B., Du, M., Geng, Z., Wei, J., Guan, R., An, S. and Zhao, W., 2022. The vital hormone 20-hydroxyecdysone controls ATP production by upregulating the binding of trehalase 1 with ATP synthase subunit α in Helicoverpa armigera. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 298(2).

(3) Tellis, M., Mohite, S. and Joshi, R., 2024. Trehalase inhibition in Helicoverpa armigera activates machinery for alternate energy acquisition. Journal of Biosciences, 49(3), p.74.

(4) Jiang, T., Ma, L., Liu, X.Y., Xiao, H.J. and Zhang, W.N., 2019. Effects of starvation on respiratory metabolism and energy metabolism in the cotton bollworm Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner)(Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Journal of Insect Physiology, 119, p.103951.

The authors have used this transcriptomic data for pathway enrichment analysis, which led to the E2F family of transcription factors and a reduction in the level of when trehalose metabolism is perturbed. EMSA experiments, though, confirm a possibility of the E2F interaction with the HaTPS/TPP promoter, but it lacks proper controls and competition to test the actual specificity of this interaction. Several transcription factors have DNA-binding domains and could bind any given DNA weakly, and the specificity is ideally known only from competitive and non-competitive inhibition studies.

We thank the reviewer for this important comment and fully agree that EMSA alone, without appropriate competition and control reactions, cannot establish the specificity or functional relevance of a transcription factor-DNA interaction. In our study, we found the E2F family from GRN analysis of the RNA seq data obtained upon HaTPS/TPP silencing, suggesting a potential regulatory connection. After that, we predicted E2F binding sites on the promoter of HaTPS/TPP. The EMSA experiments were intended as preliminary evidence that E2F can associate with the HaTPS/TPP promoter in vitro. We will clarify this in the manuscript by softening our conclusion to indicate that our data support a “possible E2F-HaTPS/TPP interaction”. We also perform EMSA with specific and non‑specific competitors to confirm the E2F binding to the HaTPS/TPP promoter.

The work seems to have connected the trehalose metabolism with gene expression changes, though this is an interesting idea, there are no experiments that are conclusive in the current version of the manuscript. If the authors can search for domains in the E2F family of transcription factors that can bind to the metabolite, then, if not, a chip-seq is essential to conclusively suggest the role of E2F in regulating gene expression tuned by the metabolites.

A previous study in D. melanogaster, Zappia et al., (2016) showed vital role of E2F in skeletal muscle required for animal viability. They have shown that Dp knockdown resulted in reduced expression of genes encoding structural and contractile proteins, such as Myosin heavy chain (Mhc), fln, Tropomyosin 1 (Tm1), Tropomyosin 2 (Tm2), Myosin light chain 2 (Mlc2), sarcomere length short (sals) and Act88F, and myogenic regulators, such as held out wings (how), Limpet (Lmpt), Myocyte enhancer factor 2 (Mef2) and spalt major (salm). Also, ChiP-qRT-PCR showed upstream regions of myogenic genes, such as how, fln, Lmpt, sals, Tm1 and Mef2, were specifically enriched with E2f1, E2f2, and Dp antibodies in comparison with a nonspecific antibody. Further, Zappia et al. (2019) reported a chip-seq dataset that suggests that E2F/Dp directly activates the expression of glycolytic and mitochondrial genes during muscle development. Zappia et al., (2023) showed the regulation of one of the glycolytic genes, Phosphoglycerate kinase (Pgk) by E2F during Drosophila development.

However, the regulation of trehalose metabolic genes by E2F/Dp and vice versa was not studied previously. So here in our study, we tried to understand the correlation of trehalose metabolism and E2F/Dp in the muscle development of H. armigera.

References:

(1) Zappia, M.P. and Frolov, M.V., 2016. E2F function in muscle growth is necessary and sufficient for viability in Drosophila. Nature Communications, 7(1), p.10509.

(2) Zappia, M.P., Rogers, A., Islam, A.B. and Frolov, M.V., 2019. Rbf activates the myogenic transcriptional program to promote skeletal muscle differentiation. Cell reports, 26(3), pp.702-719.

(3) Zappia, M. P., Kwon, Y.-J., Westacott, A., Liseth, I., Lee, H. M., Islam, A. B., Kim, J., & Frolov, M. V. (2023a). E2F regulation of the Phosphoglycerate kinase gene is functionally important in Drosophila development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(15), e2220770120.

Some of the above concerns are partially addressed in experiments where silencing of E2F/Dp shows similar phenotypes as with NPP and dsRNA. It is also notable that silencing any key transcription factor can have several indirect effects, and delayed pupation and lethality could not be definitely linked to trehalose-dependent regulation.

Yes. It’s true that silencing of any key transcription factor can have several indirect effects. Our intention was not to argue that delayed pupation and lethality are exclusively due to trehalose-dependent regulation, but that E2F/Dp and HaTPS/TPP silencing showed a consistent set of phenotypes and molecular changes, such as (i) transcriptomic enrichment of E2F targets upon trehalose perturbation, (ii) reduced HaTPS/TPP expression following E2F/Dp silencing, (iii) reduced myogenic gene expression that parallels the phenotypes observed with HaTPS/TPP silencing and (iv) restoration of E2F and Dp expression in E2F/Dp‑silenced insects upon trehalose feeding in the rescue assay. Together, these findings support a functional association between E2F/Dp and trehalose homeostasis. At the same time, we fully acknowledge that these results do not exclude additional, trehalose‑independent roles of E2F/Dp in development.

Trehalose rescue experiments that rescue phenotype and gene expression are interesting. But is it possible that the fed trehalose is metabolized in the gut and might not reach the target tissue? In which case, the role of trehalose in directly regulating transcription factors becomes questionable. So, a confirmatory experiment is needed to demonstrate that the fed trehalose reaches the target tissues. This could possibly be done by measuring the trehalose levels in muscles post-rescue feeding. Also, rescue experiments need to be done with appropriate control sugars.

Yes, it’s possible that, to some extent, trehalose is metabolized in the gut. Even though trehalase is present in the insect gut, some of the trehalose will be absorbed via trehalose transporters on the gut lining. Trehalose feeding was not rescued in insects fed with the control diet (empty vector and dsHaTPP), which contains chickpea powder, which is composed of an ample amount of amino acids and carbohydrates. Insects fed exclusively on a trehalose-containing diet are rescued, but not on a control diet that contains other carbohydrates. We agree that direct measurement of trehalose in target tissues will provide important confirmation. In the manuscript, we will measure trehalose levels in muscle, gut, and haemolymph after trehalose feeding.

No experiments are performed with non-target control dsRNA. All the experiments are done with an empty vector. But an appropriate control should be a non-target control.

Yes, there was no experiment with non-target dsRNA. Earlier, we have optimized a protocol for dsRNA delivery and its effectiveness in target knockdown (concentration, time) experiment, and published several research articles using a similar protocol:

(1) Chaudhari, B.Y., Nichit, V.J., Barvkar, V.T. and Joshi, R.S., 2025. Mechanistic insights in the role of trehalose transporter in metabolic homeostasis in response to dietary trehalose. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics, p. jkaf303.

(2) Barbole, R.S., Sharma, S., Patil, Y., Giri, A.P. and Joshi, R.S., 2024. Chitinase inhibition induces transcriptional dysregulation altering ecdysteroid-mediated control of Spodoptera frugiperda development. Iscience, 27(3).

(3) Patil, Y.P., Wagh, D.S., Barvkar, V.T., Gawari, S.K., Pisalwar, P.D., Ahmed, S. and Joshi, R.S., 2025. Altered Octopamine synthesis impairs tyrosine metabolism affecting Helicoverpa armigera vitality. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology, 208, p.106323.

(4) Tellis, M.B., Chaudhari, B.Y., Deshpande, S.V., Nikam, S.V., Barvkar, V.T., Kotkar, H.M. and Joshi, R.S., 2023. Trehalose transporter-like gene diversity and dynamics enhances stress response and recovery in Helicoverpa armigera. Gene, 862, p.147259.

(5) Joshi, K.S., Barvkar, V.T., Hadapad, A.B., Hire, R.S. and Joshi, R.S., 2025. LDH-dsRNA nanocarrier-mediated spray-induced silencing of juvenile hormone degradation pathway genes for targeted control of Helicoverpa armigera. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, p.148673.

The same vector backbone and preparation procedures were used for both control and experimental constructs, allowing us to specifically compare the effects of the target dsRNA. The phenotypes and gene expression changes we observed were specific to the target genes and were not seen in the empty vector controls, suggesting that the effects are not due to nonspecific responses of dsRNA delivery or vector components.

We acknowledge your suggestions, and in future studies, we will keep non-target dsRNA as a control in silencing assays.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

This study shows that the knockdown of the effects of TPS/TPP in Helicoverpa armigera and Spodoptera frugiperda can be rescued by trehalose treatment. This suggests that trehalose metabolism is necessary for development in the tissues that NPP and dsRNA can reach.

Strengths:

This study examines an important metabolic process beyond model organisms, providing a new perspective on our understanding of species-specific metabolism equilibria, whether conserved or divergent.

Weaknesses:

While the effects observed may be truly conserved across Lepidopterans and may be muscle-specific, the study largely relies on one species and perturbation methods that are not muscle-specific. The technical limitations arising from investigations outside model systems, where solid methods are available, limit the specificity of inferences that may be drawn from the data.

Thank you for this potting out this experimental weakness. We will validate the gene expression data using qRT-PCR on muscle tissue samples from both treated and control groups. We will also perform metabolite analysis with muscle samples. This will help to determine whether the observed gene expression patterns and metabolite changes are muscle-specific or systemic.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

The hypothesis is that Trehalose metabolism regulates transcriptional control of muscle development in lepidopteran insects.

The manuscript investigates the role of Trehalose metabolism in muscle development. Through sequencing and subsequent bioinformatics analysis of insects with perturbed trehalose metabolism (knockdown of TPS/TPP), the authors have identified transcription factor E2F, which was validated through RT-PCR. Their hypothesis is that trehalose metabolism regulates E2F, which then controls the myogenic genes. Counterintuitive to this hypothesis, the investigators perform EMSAs with the E2F protein and promoter of the TPP gene and show binding. Their knockdown experiments with Dp, the binding partner of E2F, show direct effect on several trehalose metabolism genes. Similar results are demonstrated in the trehalose feeding experiment, where feeding trehalose leads to partial rescue of the phenotype observed as a result of Dp knockdown. This seems contradictory to their hypothesis. Even more intriguing is a similar observation between paramyosin, a structural muscle protein, and E2F/Dp - they show that paramyosin regulates E2F/Dp and E2F/Dp regulated paramyosin. The only plausible way to explain the results is the existence of a feed-forward loop between TPP-E2F/Dp and paramyosin-E2F/Dp. But the authors have mentioned nothing in this line. Additionally, I think trehalose metabolism impacts amino acid content in insects, and that will have a direct bearing on muscle development. The sequencing analysis and follow-up GSEA studies have demonstrated enrichment of several amino acid biosynthetic genes. Yet authors make no efforts to measure amino acid levels or correlate them with muscle development. Any study aiming to link trehalose metabolism and muscle development and not considering the above points will be incomplete.

We appreciate the reviewer’s efforts in the careful evaluation of this manuscript and constructive comments. From our and earlier data we found it was difficult to consider linear pathway “trehalose → E2F → muscle,” but rather a regulatory module in which trehalose metabolism and E2F/Dp form an interdependent circuit controlling myogenic genes. E2F/Dp binds and activates trehalose metabolism genes (TPS/TPP, Treh1) and myogenic structural genes, consistent with EMSA (TPS/TPP-E2F) and predicted binding sites of E2F on metabolic genes, Treh1, Pgk, and myogenic genes such as Act88F, Prm, Tm1, Fln, etc. At the same time, perturbing trehalose synthesis reduces E2F/Dp expression and myogenic gene expression, and trehalose feeding partially restores all three. This bidirectional influence is similar to E2F‑dependent control of carbohydrate metabolism and systemic sugar homeostasis described in D. melanogaster, where E2F/Dp both regulates metabolic genes and is itself constrained by metabolic state (Zappia et al., 2023a; Zappia et al., 2021).

The reciprocal regulation between Prm and E2F/Dp is indeed intriguing. Rather than a paradox, we interpret this as evidence that E2F/Dp couples metabolic genes and structural muscle genes within a shared module, and that key sarcomeric components (such as paramyosin) feed back on this transcriptional program. Similar cross‑talk between E2F‑controlled metabolic programs and tissue function has been documented in D. melanogaster muscle and fat body, where E2F loss in one tissue elicits systemic changes in the other (Zappia et al., 2021). For further confirmation of E2F-regulated Prm, we will perform EMSA on the Prm promoter with appropriate controls.

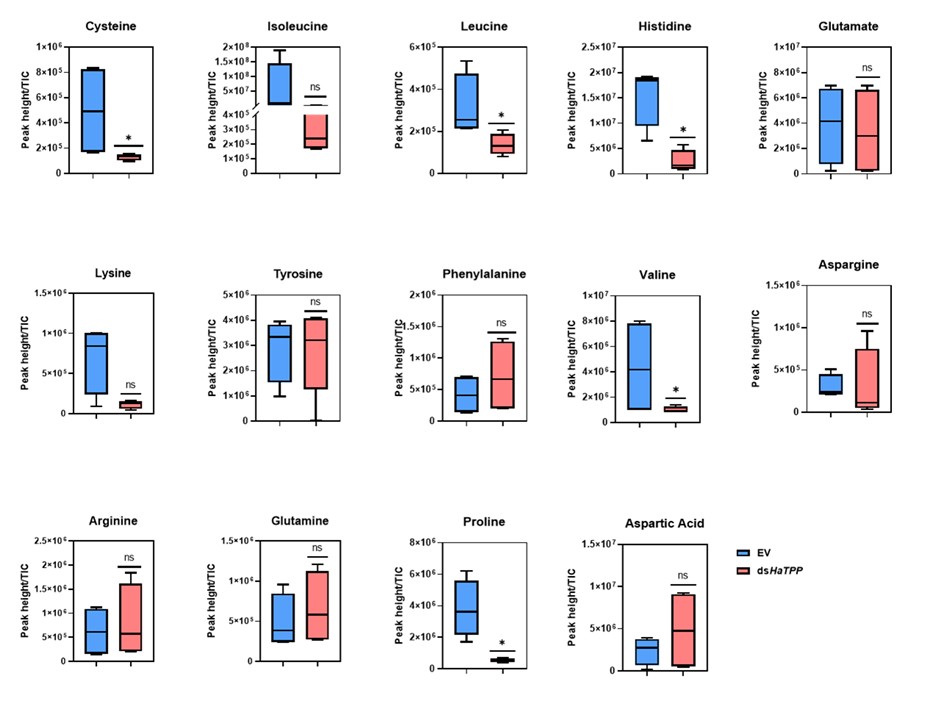

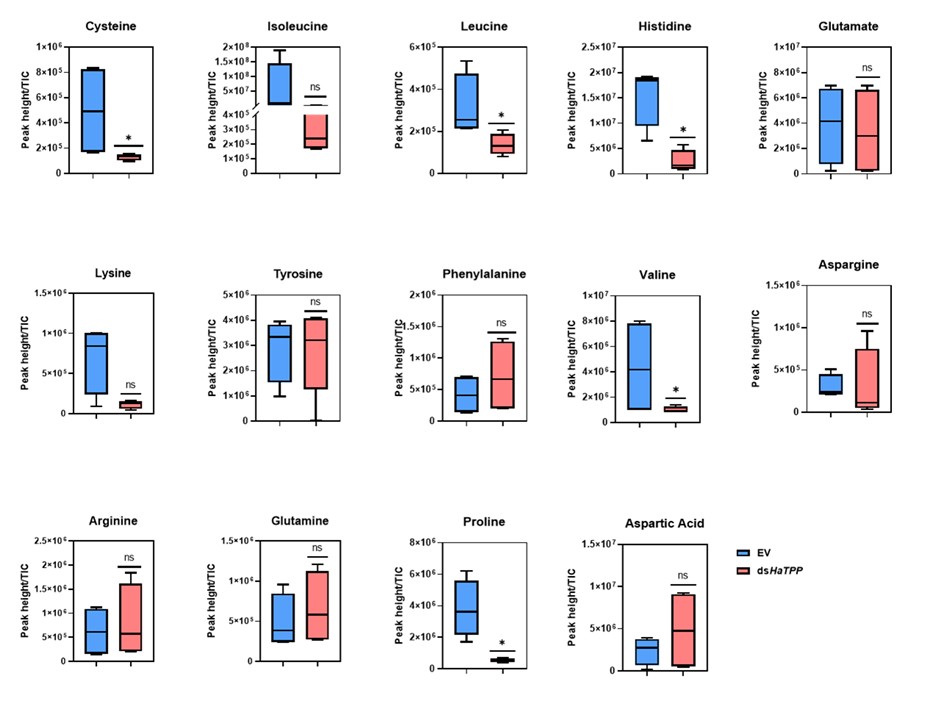

We fully agree that amino‑acid metabolism is a critical missing piece. In the manuscript, we will quantify the amino acid levels and include the results: “Amino acids display differential levels showing cysteine, leucine, histidine, valine, and proline showed significant reductions, while isoleucine and lysine showed non-significant reductions upon trehalose metabolism perturbation. These results are consistent with previous reports published by Tellis et al. (2024) and Shi et al. (2016)”. We will reframe our conclusions more cautiously as establishing a trehalose-E2F/Dp-muscle development, while stating that “definitive causal links via amino‑acid metabolism remain to be demonstrated”.

Reference:

(1) Zappia, M. P., Kwon, Y.-J., Westacott, A., Liseth, I., Lee, H. M., Islam, A. B., Kim, J., & Frolov, M. V. (2023a). E2F regulation of the Phosphoglycerate kinase gene is functionally important in Drosophila development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(15), e2220770120.

(2) Zappia, M.P., Guarner, A., Kellie-Smith, N., Rogers, A., Morris, R., Nicolay, B., Boukhali, M., Haas, W., Dyson, N.J. and Frolov, M.V., 2021. E2F/Dp inactivation in fat body cells triggers systemic metabolic changes. elife, 10, p.e67753.

(3)Tellis, M., Mohite, S. and Joshi, R., 2024. Trehalase inhibition in Helicoverpa armigera activates machinery for alternate energy acquisition. Journal of Biosciences, 49(3), p.74.

(4) Shi, J.F., Xu, Q.Y., Sun, Q.K., Meng, Q.W., Mu, L.L., Guo, W.C. and Li, G.Q., 2016. Physiological roles of trehalose in Leptinotarsa larvae revealed by RNA interference of trehalose-6-phosphate synthase and trehalase genes. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 77, pp.52-68.

Author response image 1.

The result section of the manuscript is quite concise, to my understanding (especially the initial few sections), which misses out on mentioning details that would help readers understand the paper better. While technical details of the methods should be in the Materials and Methods section, the overall experimental strategy for the experiments performed should be explained in adequate detail in the results section itself or in figure legends. I would request authors to include more details in the results section. As an extension of the comment above, many times, abbreviations have been used without introducing them. A thorough check of the manuscript is required regarding this.

Thank you very much for pointing out this issue. We will revise the manuscript content according to these suggestions.

The Spodoptera experiments appear ad hoc and are insufficient to support conservation beyond Helicoverpa. To substantiate this claim, please add a coherent, minimal set of Spodoptera experiments and present them in a dedicated subsection. Alternatively, consider removing these data and limiting the conclusions (and title) to H. armigera.

We thank the reviewer for this helpful comment. We agree that, in this current version of the manuscript, the S. frugiperda experiments are not sufficiently systematic to support strong claims about conservation beyond H. armigera. Our primary focus in this study is indeed on H. armigera, and the addition of the S. frugiperda data was intended only as preliminary, supportive evidence rather than a central component of our conclusions. To avoid over‑interpretation and to keep the manuscript focused and coherent, we will remove all S. frugiperda data from the revised version, including the corresponding text and figures. We will also adjust the title, abstract, and conclusion to clearly state that our findings are limited to H. armigera.

In order to check the effects of E2F/Dp, a dsRNA-mediated knockdown of Dp was performed. Why was the E2F protein, a primary target of the study, not chosen as a candidate? The authors should either provide justification for this or perform the suggested experiments to come to a conclusion. I would like to point out that such experiments were performed in Drosophila.

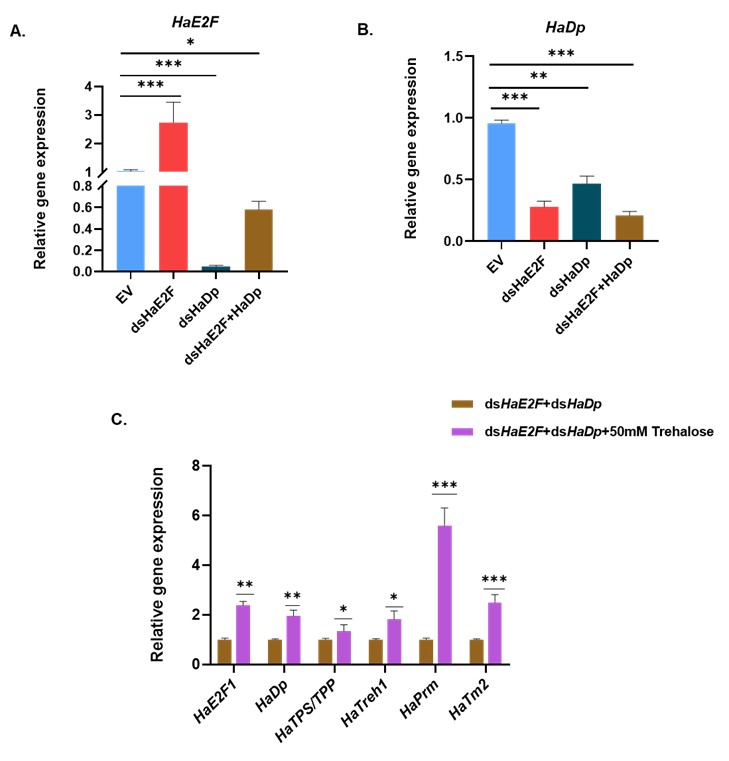

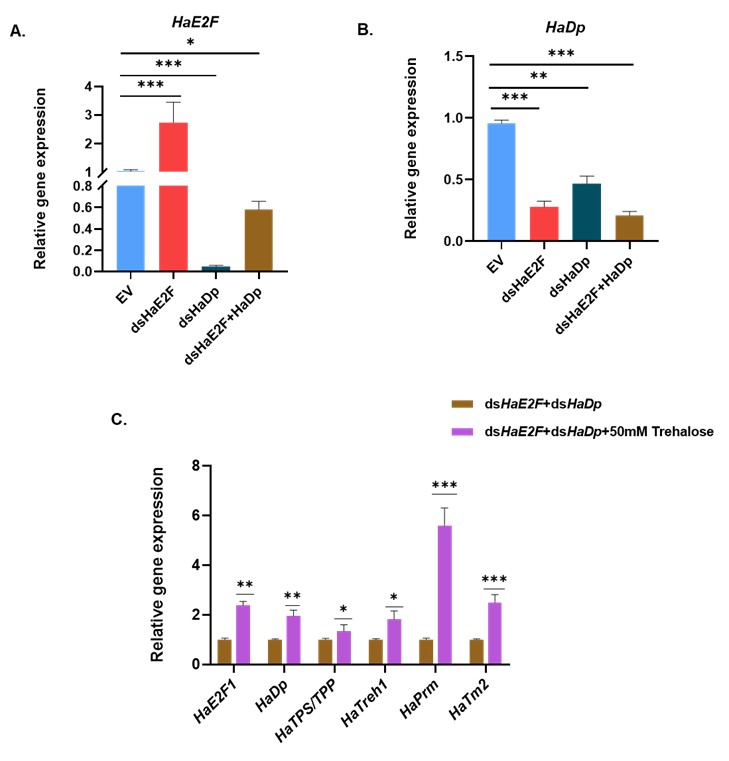

Thank you for this thoughtful comment and the specific suggestion. We agree that directly targeting E2F would, in principle, be an informative complementary approach. In our study, however, we prioritized Dp knockdown for two main reasons. First, E2F is a large family, and E2F-Dp functions as an obligate heterodimer. Previous work in D. melanogaster has shown that depletion of Dp is sufficient to disrupt E2F-dependent transcription broadly, often with more efficient loss of complex activity than targeting individual E2F isoforms (Zappia et al., 2021; Zappia et al., 2016). Second, in our preliminary trials, we performed a dsRNA feeding assay with dsHaE2F, dsHaDp, and combined dsHaE2F plus dsHaDp. In that assay, we did not achieve silencing of E2F in dsRNA targeting HaE2F (dsHaE2F). So here, as E2F is a large family, other E2F isoforms may be compensating for the silencing effect of targeted HaE2F. However, HaE2F showed significantly reduced expression upon dsHaDp and combined dsHaE2F plus dsHaDp feeding (Figure A), whereas HaDp showed a significant reduction in its expression in all three conditions (Figure B). As we observed reduced expression of both HaE2F and HaDp upon combined feeding of dsHaE2F and dsHaDp, we further performed a rescue assay by exogenous feeding of trehalose. We observed the significant upregulation of HaE2F, HaDp, trehalose metabolic genes (HaTPS/TPP and HaTreh1), and myogenic genes (HaPrm and HaTm2) (Figure C). For these reasons, we focused on Dp silencing as a more reliable way to impair E2F/Dp complex function in H. armigera.

Author response image 2.

References:

(1) Zappia, M.P. and Frolov, M.V., 2016. E2F function in muscle growth is necessary and sufficient for viability in Drosophila. Nature Communications, 7(1), p.10509.

(2) Zappia, M.P., Guarner, A., Kellie-Smith, N., Rogers, A., Morris, R., Nicolay, B., Boukhali, M., Haas, W., Dyson, N.J. and Frolov, M.V., 2021. E2F/Dp inactivation in fat body cells triggers systemic metabolic changes. elife, 10, p.e67753.

Silencing of HaDp resulted in a significant decrease in HaE2F expression. I find this observation intriguing. DP is the cofactor of E2F, and they both heterodimerise and sit on the promoter of target genes to regulate them. I would request authors to revisit this result, as it contradicts the general understanding of how E2F/Dp functions in other organisms. If Dp indeed controls E2F expression, then further experiments should be conducted to come to a conclusion convincingly. Additionally, these results would need thorough discussion with citations of similar results observed for other transcription factor-cofactor complexes.

Thank you for highlighting this point and for prompting us to examine these data more carefully. Silencing HaDp leading to reduced HaE2F mRNA is indeed unexpected if one only considers the canonical view of E2F/Dp as a heterodimer that co-occupies target promoters without strongly regulating each other’s expression. However, several lines of work suggest that transcription factor-cofactor networks frequently include feedback loops in which cofactors influence the expression of their partner TFs. First, in multiple systems, transcription factors and their cofactors are known to regulate each other’s transcription, forming positive or negative feedback loops. For example, in hematopoietic cells, the transcription factor Foxp3 controls the expression of many of its own cofactors, and some of these cofactors in turn facilitate or stabilize Foxp3 expression, forming an interconnected regulatory network rather than a simple one‑way interaction (Rudra et al., 2012). Second, E2F/Dp complexes exhibit non‑canonical regulatory mechanisms and can regulate broad sets of targets, including other transcriptional regulators. Several studies show that E2F/Dp proteins not only control classical cell‑cycle genes but also participate in diverse processes such as DNA damage signaling, mitochondrial function, and differentiation (Guarner et al., 2017; Ambrus et al., 2013; Sánchez-Camargo et al., 2021). In D. melanogaster, complete loss of dDP alters the expression of direct targets E2F/DP, including dATM (Guarner et al., 2017).

All these reports indicate that the E2F-Dp complex sits at the top of multi‑layer regulatory hierarchies. Such architectures make it plausible that Dp silencing in H. armigera could modulate HaE2F expression in a non-canonical way.

References:

(1) Rudra, D., DeRoos, P., Chaudhry, A., Niec, R.E., Arvey, A., Samstein, R.M., Leslie, C., Shaffer, S.A., Goodlett, D.R. and Rudensky, A.Y., 2012. Transcription factor Foxp3 and its protein partners form a complex regulatory network. Nature immunology, 13(10), pp.1010-1019.

(2) Guarner, A., Morris, R., Korenjak, M., Boukhali, M., Zappia, M.P., Van Rechem, C., Whetstine, J.R., Ramaswamy, S., Zou, L., Frolov, M.V. and Haas, W., 2017. E2F/DP prevents cell-cycle progression in endocycling fat body cells by suppressing dATM expression. Developmental cell, 43(6), pp.689-703.

(3) Ambrus, A.M., Islam, A.B., Holmes, K.B., Moon, N.S., Lopez-Bigas, N., Benevolenskaya, E.V. and Frolov, M.V., 2013. Loss of dE2F compromises mitochondrial function. Developmental cell, 27(4), pp.438-451.

(4) Sánchez-Camargo, V.A., Romero-Rodríguez, S. and Vázquez-Ramos, J.M., 2021. Non-canonical functions of the E2F/DP pathway with emphasis in plants. Phyton, 90(2), p.307.

I consider the overall bioinformatics analysis to remain very poorly described. What is specifically lacking is clear statements about why a particular dry lab experiments were conducted.

We again thank the reviewer for advising us to give a biological context/motivation for every bioinformatics analysis performed. The bioinformatics analyses devised here, try to explain the systems-level perturbations of HaTPS/TPP silencing to explain the observed phenotype and to discover transcription factors potentially modulating the HaTPS/TPP induced gene regulatory changes.

(1) Gene set enrichment analyses:

Differential gene expression analyses of the bulk RNA sequencing data followed by qRT-PCR confirmed the transcriptional changes in myogenic genes and gene expression alterations in metabolic and cell cycle-related genes. These perturbations merely confirmed the effect induced by HaTPS/TPP silencing in obviously expected genes. We wanted to see whether using an “unbiased” system-level statistical analyses like gene set enrichment analyses (GSEA), can reveal both expected and novel biological processes that underlie HaTPS/TPP silencing. GSEA results revealed large-scale transcriptional changes in 11 enriched processes, including amino acid metabolism, energy metabolism, developmental regulatory processes, and motor protein activity. GSEA not only divulged overall transcriptionally enriched pathways but also identified the genes undergoing synchronized pathway-level transcriptional change upon HaTPS/TPP silencing.

(2) Gene regulatory network analysis:

Although GSEA uncovered potential pathway-level changes, we were also interested in identifying the gene regulatory network associated with such large-scale process-level transcriptional perturbations. Interestingly, the biological processes undergoing perturbations were also heterogeneous (e.g., motor protein activity, energy metabolism, amino acid metabolism, etc.). We hypothesized that the inference of a causal gene regulatory network associated with the genes associated with GSEA-enriched biological processes should predict core/master transcription factors that might synchronously regulate metabolic and non-metabolic processes related to HaTPS/TPP silencing, thereby providing a broad understanding of the perturbed phenotype. The gene regulatory network analysis statistically inferred an “active” gene regulatory network corresponding to the GSEA-enriched KEGG gene sets. Ranking the transcription factors (TFs) based on the number of outgoing connections (outdegree centrality) within the active gene regulatory network, E2F family TFs were identified to be top-ranking, highly connected transcription factors associated with the transcriptionally enriched processes. This suggests that E2F family TFs are central to controlling the flow of regulatory information within this network. Intriguingly, E2F has been previously implicated in muscle development in insects (Zappia et al., 2016). Further extracting the regulated targets of E2F family TFs within this network revealed the mechanistic connection with the 11 enriched processes. This GRN analysis was crucial in discovering and prioritizing E2F TFs as central transcription factors mediating HaTPS/TPP silencing effects, which was not apparent using trivial analyses like differential gene expression analysis.

As per the reviewer’s suggestions, we will add these outlined points in the text of the manuscript (Results section) to further give context and clarity to the bioinformatics analyses conducted in this study.

In my judgement, the EMSA analysis presented is technically poor in quality. It lacks positive and negative controls, does not show mutation analysis or super shifts. Also, it lacks any competition assays that are important to prove the binding beyond doubt. I am not sure why protein is not detected at all in lower concentrations. Overall, the EMSA assays need to be redone; I find the current results to be unacceptable.

Thank you for pointing out this issue. We will reperform the EMSA analysis with appropriate controls. Although the gel image was not clear, there was a light band of protein (indicated by the white square) observed in well No. 8, where we used 8 μg of E2F protein and 75 ng of HaTPS/TPP promoter, upon gel stained with SYPRO Ruby protein stain, suggesting weak HaTPS/TPP-E2F complex formation.

GSEA studies clearly indicate enrichment of the amino acid synthesis gene in TPP knockdown samples. This supports the plausible theory that a lack of Trehalose means a lack of enough nutrients, therefore less of that is converted to amino acids, and therefore muscle development is compromised. Yet the authors make no effort to measure amino acid levels. While nutrients can be sensed through signalling pathways leading to shut shutdown of myogenic genes, a simple and direct correlation between less raw material and deformed muscle might also be possible.

We quantified amino acid levels as per the suggestion, and we observed differential levels of amino acids upon trehalose metabolism perturbation.

However, we observed that insect were failed to rescue when fed a control chickpea-based artificial diet that contained nutrients required for normal growth and development. Based on this observation, we conclude that trehalose deficiency is the only possible cause for the defect in muscle development.

The authors are encouraged to stick to one color palette while demonstrating sequencing results. Choosing a different color palette for representing results from the same sequencing analysis confuses readers.

Thank you for the comment. We will revise the color palette as per the suggestion.

Expression of genes, as understood from sequencing analysis in Figure 1D, Figure 2F, and Figure 3D, appears to be binary in nature. This result is extremely surprising given that the qRT-PCR of these genes have revealed a checker and graded expression.

Thank you for pointing out this issue. We will revise the scale range for these figures to get more insights about gene expression levels and include figures as per the suggestion.

In several graphs, non-significant results have been interpreted as significant in the results section. In a few other cases, the reported changes are minimal, and the statistical support is unclear; please recheck the analyses and include exact statistics. In the results section, fold changes observed should be discussed, as well as the statistical significance of the observed change.

We will revise the analyses and include exact statistics as per the suggestion.

Finally, I would add that trehalose metabolism regulates cell cycle genes, and muscle development genes establish correlation and causation. The authors should ensure that any comments they make are backed by evidence.

We thank the reviewer for this insightful comment. Although direct evidence in insects is currently lacking, multiple independent studies in yeast, plants and mammalian systems support a regulatory link between trehalose metabolism and the cell cycle. In budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, neutral Treh (Nth1) is directly phosphorylated and activated by the major cyclin‑dependent kinase Cdk1 at G1/S, routing stored trehalose into glycolysis to fuel DNA replication and mitosis (Ewald et al., 2016). CDK‑dependent regulation of trehalase activity has also been reported in plants, where CDC28‑mediated phosphorylation channels glucose into biosynthetic pathways necessary for cell proliferation (Lara-núñez et al., 2025). Furthermore, budding yeast cells accumulate trehalose and glycogen upon entry into quiescence and subsequently mobilize these stores to generate a metabolic “finishing kick” that supports re‑entry into the cell cycle (Silljé et al., 1999; Shi et al., 2010). Exogenous trehalose that perturbs the trehalose cycle impairs glycolysis, reduces ATP, and delays cell cycle progression in S. cerevisiae, highlighting a dose‑ and context‑dependent control of growth versus arrest (Zhang, Zhang and Li, 2020). In mammalian systems, trehalose similarly modulates proliferation-differentiation decisions. In rat airway smooth muscle cells, low trehalose concentrations promote autophagy, whereas higher doses induce S/G2–M arrest, downregulate Cyclin A1/B1, and trigger apoptosis, indicating a shift from controlled growth to cell elimination at higher exposure (Xiao et al., 2021). In human iPSC‑derived neural stem/progenitor cells, low‑dose trehalose enhances neuronal differentiation and VEGF secretion, while higher doses are cytotoxic, again highlighting a tunable impact on cell‑fate outcomes (Roose et al., 2025). In wheat, exogenous trehalose under heat stress reduces growth, lowers auxin, gibberellin, abscisic acid and cytokinin levels, and represses CycD2 and CDC2 expression, suggesting that trehalose signalling integrates with hormone pathways and core cell‑cycle regulators to restrain proliferation during stress (Luo, Liu, and Li, 2021). Together, these studies showed the importance of trehalose metabolism in cell‑cycle regulation to decide whether cells and tissues proliferate, differentiate, or remain quiescent.

With respect to muscle development, previous work has implicated glycolytic metabolism in myogenesis and muscle growth. Tixier et al. (2013) showed that loss of key glycolytic genes results in abnormally thin muscles, while Bawa et al. (2020) demonstrated that loss of TRIM32 decreases glycolytic flux and reduces muscle tissue size. These findings indicate that carbohydrate and energy metabolism pathways are important determinants of muscle structure and growth. However, there are no previous studies about the role of trehalose metabolism in muscle development, other than as an energy source, so here we specifically set out to establish the involvement of trehalose metabolism in muscle development.

References:

(1) Ewald, J.C. et al. (2016) “The yeast cyclin-dependent kinase routes carbon fluxes to fuel cell cycle progression,” Molecular cell, 62(4), pp. 532–545.

(2) Lara-núñez, A. et al. (2025) “The Cyclin-Dependent Kinase activity modulates the central carbon metabolism in maize during germination,” (January), pp. 1–16.

(3) Silljé, H.H.W. et al. (1999) “Function of trehalose and glycogen in cell cycle progression and cell viability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae,” Journal of bacteriology, 181(2), pp. 396–400.

(4) Shi, L. et al. (2010) “Trehalose Is a Key Determinant of the Quiescent Metabolic State That Fuels Cell Cycle Progression upon Return to Growth,” 21, pp. 1982–1990.

(5) Zhang, X., Zhang, Y. and Li, H. (2020) “Regulation of trehalose, a typical stress protectant, on central metabolisms, cell growth and division of Saccharomyces cerevisiae CEN. PK113-7D,” Food Microbiology, 89, p. 103459.

(6) Xiao, B. et al. (2021) “Trehalose inhibits proliferation while activates apoptosis and autophagy in rat airway smooth muscle cells,” Acta Histochemica, 123(8), p. 151810.

(7) Roose, S.K. et al. (2025) “Trehalose enhances neuronal differentiation with VEGF secretion in human iPSC-derived neural stem / progenitor cells,” Regenerative Therapy, 30, pp. 268–277.

(8) Luo, Y., Liu, X. and Li, W. (2021) “Exogenously-supplied trehalose inhibits the growth of wheat seedlings under high temperature by affecting plant hormone levels and cell cycle processes,” Plant Signaling & Behavior, 16(6).

(9) Tixier, V., Bataillé, L., Etard, C., Jagla, T., Weger, M., DaPonte, J.P., Strähle, U., Dickmeis, T. and Jagla, K., 2013. Glycolysis supports embryonic muscle growth by promoting myoblast fusion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(47), pp.18982-18987.

(10) Bawa, S., Brooks, D.S., Neville, K.E., Tipping, M., Sagar, M.A., Kollhoff, J.A., Chawla, G., Geisbrecht, B.V., Tennessen, J.M., Eliceiri, K.W. and Geisbrecht, E.R., 2020. Drosophila TRIM32 cooperates with glycolytic enzymes to promote cell growth. elife, 9, p.e52358.

Finally, we appreciate the meticulous review of this manuscript and constructive comments. We will perform the recommended experiments, data analysis, and revise the manuscript accordingly.