Author response:

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

Thach et al. report on the structure and function of trimethylamine N-oxide demethylase (TDM). They identify a novel complex assembly composed of multiple TDM monomers and obtain high-resolution structural information for the catalytic site, including an analysis of its metal composition, which leads them to propose a mechanism for the catalytic reaction.

In addition, the authors describe a novel substrate channel within the TDM complex that connects the N-terminal Zn²-dependent TMAO demethylation domain with the C-terminal tetrahydrofolate (THF)-binding domain. This continuous intramolecular tunnel appears highly optimized for shuttling formaldehyde (HCHO), based on its negative electrostatic properties and restricted width. The authors propose that this channel facilitates the safe transfer of HCHO, enabling its efficient conversion to methylenetetrahydrofolate (MTHF) at the C-terminal domain as a microbial detoxification strategy.

Strengths:

The authors provide convincing high-resolution cryo-EM structural evidence (up to 2 Å) revealing an intriguing complex composed of two full monomers and two half-domains. They further present evidence for the metal ion bound at the active site and articulate a plausible hypothesis for the catalytic cycle. Substantial effort is devoted to optimizing and characterizing enzyme activity, including detailed kinetic analyses across a range of pH values, temperatures, and substrate concentrations. Furthermore, the authors validate their structural insights through functional analysis of active-site point mutants.

In addition, the authors identify a continuous channel for formaldehyde (HCHO) passage within the structure and support this interpretation through molecular dynamics simulations. These analyses suggest an exciting mechanism of specific, dynamic, and gated channeling of HCHO. This finding is particularly appealing, as it implies the existence of a unique, completely enclosed conduit that may be of broad interest, including potential applications in bioengineering.

Weaknesses:

Although the idea of an enclosed channel for HCHO is compelling, the experimental evidence supporting enzymatic assistance in the reaction of HCHO with THF is less convincing. The linear regression analysis shown in Figure 1C demonstrates a THF concentration-dependent decrease in HCHO, but the concentrations used for THF greatly exceed its reported KD (enzyme concentration used in this assay is not reported). It has previously been shown that HCHO and THF can couple spontaneously in a non-enzymatic manner, raising the possibility that the observed effect does not require enzymatic channeling. An additional control that can rule out this possibility would help to strengthen the evidence. For example, mutating the THF binding site to prevent THF binding to the protein complex could clarify whether the observed decrease in HCHO depends on enzyme-mediated proximity effects. A mutation which would specifically disable channeling could be even more convincing (maybe at the narrowest bottleneck).

We agree with the reviewer that HCHO and THF can react spontaneously in a non-enzymatic manner, and our experiments were not intended to demonstrate enzymatic channeling. The linear regression analysis in Figure 1C was designed solely to confirm that HCHO reacts with THF under our assay conditions. Accordingly, THF was titrated over a broad concentration range starting from zero, and the observed THF concentration–dependent decrease in HCHO reflects this chemical reactivity.

We do not interpret these data as evidence that the enzyme catalyzes or is required for the HCHO–THF coupling reaction. Instead, the structural observation of an enclosed channel is presented as a separate finding. We have clarified this point in the revised text to avoid overinterpretation of the biochemical data (page 2, line 16).

Another concern is that the observed decrease in HCHO could alternatively arise from a reduced production of HCHO due to a negative allosteric effect of THF binding on the active site. From this perspective, the interpretation would be more convincing if a clear coupled effect could be demonstrated, specifically, that removal of the product (HCHO) from the reaction equilibrium leads to an increase in the catalytic efficiency of the demethylation reaction.

We agree that, in principle, a decrease in detectable HCHO could also arise from an indirect effect of THF binding on enzyme activity. However, in our study the experiment was not designed to assess catalytic coupling or allosteric regulation. The assay in question monitors HCHO levels under defined conditions and does not distinguish between changes in HCHO production and downstream consumption.

Additionally, we do not interpret the observed decrease in HCHO as evidence that THF binding enhances catalytic efficiency, or that removal of HCHO shifts the reaction equilibrium. Instead, the data are presented to establish that HCHO can react with THF under the assay conditions. Any potential allosteric effects of THF on the demethylation reaction, or kinetic coupling between HCHO removal and catalysis, are beyond the scope of the current study, and are not claimed.

While the enzyme kinetics appear to have been performed thoroughly, the description of the kinetic assays in the Methods section is very brief. Important details such as reaction buffer composition, cofactor identity and concentration (Zn2+), enzyme concentration, defined temperature, and precise pH are not clearly stated. Moreover, a detailed methodological description could not be found in the cited reference (6), if I am not mistaken.

Thank you for the suggestion. We have added reference [24] to the methodological description on page 8. The Methods section has been revised accordingly on page 8 under “TDM Activity Assay,” without altering the Zn2+ concentration.

The composition of the complex is intriguing but raises some questions. Based on SDS-PAGE analysis, the purified protein appears to be predominantly full-length TDM, and size-exclusion chromatography suggests an apparent molecular weight below 100 kDa. However, the cryo-EM structure reveals a substantially larger complex composed of two full-length monomers and two half-domains.

We appreciate the reviewer’s careful analysis of the apparent discrepancy between the biochemical characterization and the cryo-EM structure. This issue is addressed in Figure S1, which may have been overlooked.

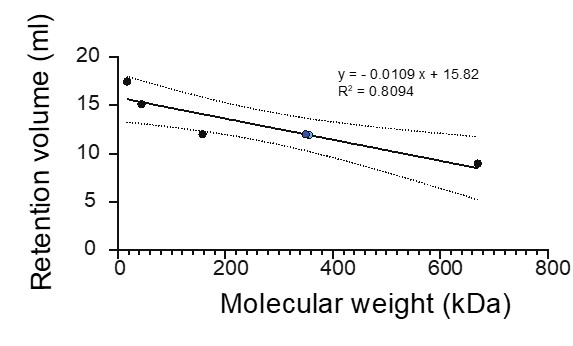

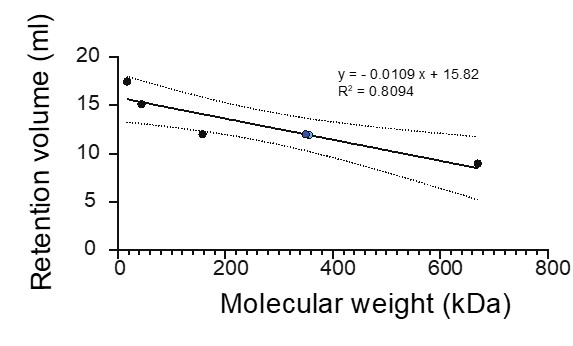

As shown in Figure S1, the stability of TDM is highly dependent on protein and salt conditions. At 150 mM NaCl, SEC reveals a dominant peak eluting between 10.5 and 12 mL, corresponding to an estimated molecular weight of ~170–305 kDa (blue dot, Author response image 1). This fraction was explicitly selected for cryo-EM analysis and yields the larger complex observed in the reconstruction. At lower salt concentrations (50 mM) or higher (>150 mM NaCl), the protein either aggregates or elutes near the void volume (~8 mL).

SDS–PAGE analysis detects full-length TDM together with smaller fragments (~40–50 kDa and ~22–25 kDa). The apparent predominance of full-length protein on SDS–PAGE likely reflects its greater staining intensity per molecule and/or a higher population, rather than the absence of truncated species.

Author response image 1.

Given the lack of clear evidence for proteolytic fragments on the SDS-PAGE gel, it is unclear how the observed stoichiometry arises. This raises the possibility of higher-order assemblies or alternative oligomeric states. Did the authors attempt to pick or analyze larger particles during cryo-EM processing? Additional biophysical characterization of particle size distribution - for example, using interferometric scattering microscopy (iSCAT)-could help clarify the oligomeric state of the complex in solution.

Cryo-EM data were collected exclusively from the size-exclusion chromatography fraction eluting between 10.5 and 12 mL. This fraction was selected to isolate the dominant assembly in solution. Extensive 2D and 3D particle classification did not reveal distinct classes corresponding to smaller species or higher-order oligomeric assemblies. Instead, the vast majority of particles converged to a single, well-defined structure consistent with the 2 full-length + 2 half-domain stoichiometry.

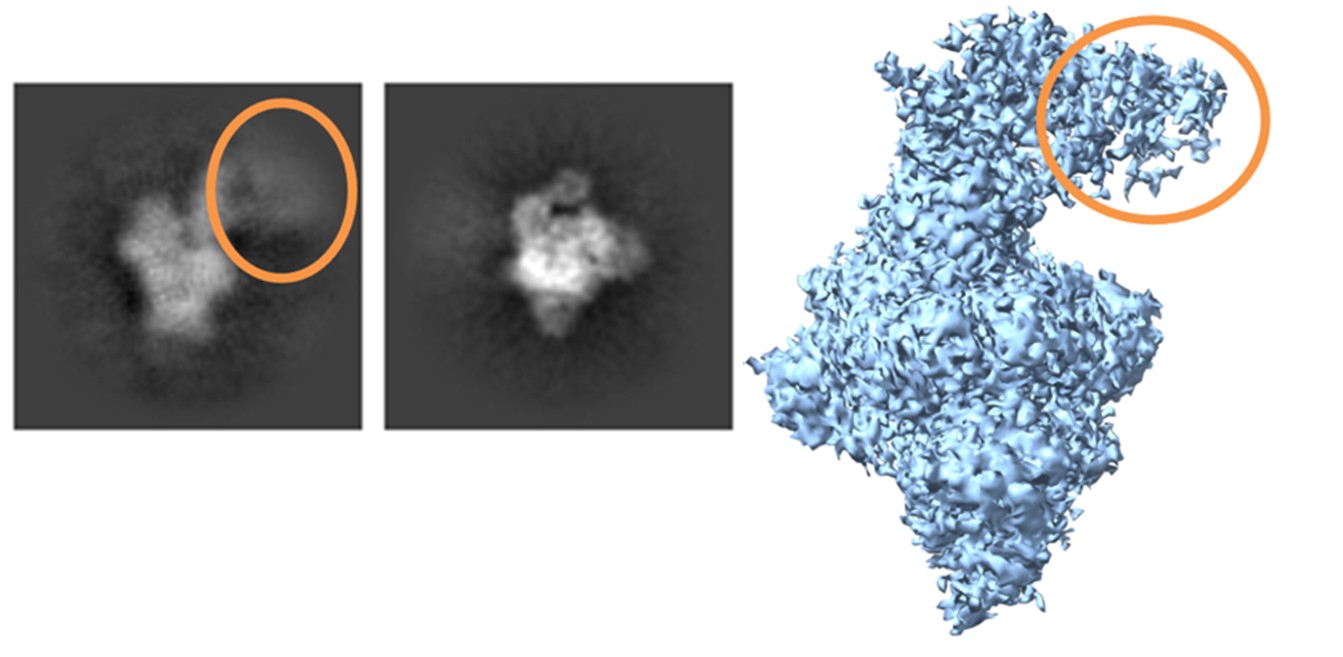

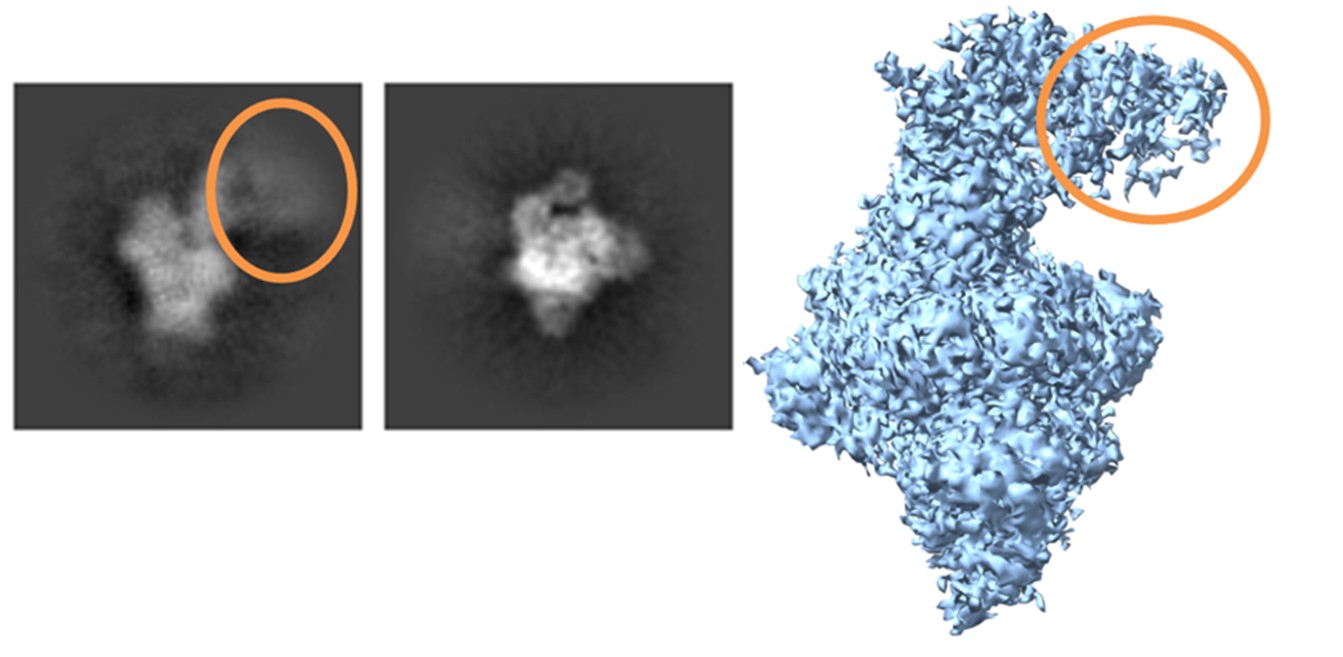

A minor subpopulation (~2%) exhibited increased flexibility in the N-terminal region of the two full-length subunits, but these particles did not form a separate oligomeric class, indicating conformational heterogeneity rather than alternative assembly states (Author response image 2). Together, these data support the 2+2½ architecture as the predominant and stable complex under the conditions used for cryo-EM. Additional techniques, such as iSCAT, would provide complementary information, but are not required to support the conclusions drawn from the SEC and cryo-EM analyses presented here.

Author response image 2.

The authors mention strict symmetry in the complex, yet C2 symmetry was enforced during refinement. While this is reasonable as an initial approach, it would strengthen the structural interpretation to relax the symmetry to C1 using the C2-refined map as a reference. This could reveal subtle asymmetries or domain-specific differences without sacrificing the overall quality of the reconstruction.

We thank the reviewer for this thoughtful suggestion. In standard cryo-EM data processing, symmetry is typically not imposed initially to minimize potential model bias; accordingly, we first performed C1 refinement before applying C2 symmetry. The resulting C1 reconstructions revealed no detectable asymmetry or domain-specific differences relative to the C2 map. In addition, relaxing the symmetry consistently reduced overall resolution, indicating lower alignment accuracy and further supporting the presence of a predominantly symmetric assembly.

In this context, the proposed catalytic role of Zn2+ raises additional questions. Why is a 2:1 enzyme-to-metal stoichiometry observed, and how does this reconcile with previous reports? This point warrants discussion. Does this imply asymmetric catalysis within the complex? Would the stoichiometry change under Zn2+-saturating conditions, as no Zn2+ appears to be added to the buffers? It would be helpful to clarify whether Zn2+ occupancy is equivalent in both active sites when symmetry is not imposed, or whether partial occupancy is observed.

The observed ~2:1 enzyme-to-Zn2+ stoichiometry likely reflects the composition of the 2 full-length + 2 half-domain (2+2½) complex. In this assembly, only the core domains that are fully present in the complex contribute to metal binding. The truncated or half-domains lack the Zn2+ binding domain. As a result, only two metal-binding sites are occupied per assembled complex, consistent with the measured stoichiometry.

We note that Zn2+ was not deliberately added to the buffers, so occupancy may not reflect full saturation. Based on our cryo-EM and biochemical data, both metal-binding sites in the full-length subunits appear to be occupied to an equivalent extent, and no clear evidence of asymmetric catalysis is observed under these current experimental conditions. Full Zn2+ saturation could potentially increase occupancy, but was not explored in these experiments.

The divalent ion Zn2+ is suggested to activate water for the catalytic reaction. I am not sure if there is a need for a water molecule to explain this catalytic mechanism. Can you please elaborate on this more? As one aspect, it might be helpful to explain in more detail how Zn-OH and D220 are recovered in the last step before a new water molecule comes in.

Thank you for your suggestion. We revised our text in page 2 as bellow.

Based on our structural and biochemical data, we propose a structurally informed working model for TMAO turnover by TDM (Scheme 1). In this model, Zn2+ plays a non-redox role by polarizing the O–H bond of the bound hydroxyl, thereby lowering its pKa. The D220 carboxylate functions as a general base, abstracting the proton to generate a hydroxide nucleophile. This hydroxide then attacks the electrophilic N-methyl carbon of TMAO, forming a tetrahedral carbinolamine (hemiaminal) intermediate. Subsequent heterolytic cleavage of the C–N bond leads to the release of HCHO. D220 then switches roles to act as a general acid, donating a proton to the departing nitrogen, which facilitates product release and regenerates the active site. This sequence allows a new water molecule to rebind Zn2+, enabling subsequent catalytic turnovers. This proposed pathway is consistent with prior mechanistic studies, in which water addition to the azomethine carbon of a cationic Schiff base generates a carbinolamine intermediate, followed by a rate-limiting breakdown to yield an amino alcohol and a carbonyl compound, in the published case, an aldehyde (Pihlaja et al., J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2, 1983, 8, 1223–1226).

Overall, the authors were successful in advancing our structural and functional understanding of the TDM complex. They suggest an interesting oligomeric complex composition which should be investigated with additional biophysical techniques.

Additionally, they provide an intriguing hypothesis for a new type of substrate channeling. Additional kinetic experiments focusing on HCHO and THF turnover by enzymatic proximity effects would strengthen this potentially fundamental finding. If this channeling mechanism can be supported by stronger experimental evidence, it would substantially advance our understanding and knowledge of biologic conduits and enable future efforts in the design of artificial cascade catalysis systems with high conversion rate and efficiency, as well as detoxification pathways.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The manuscript reports a cryo-EM structure of TMAO demethylase from Paracoccus sp. This is an important enzyme in the metabolism of trimethylamine oxide (TMAO) and trimethylamine (TMA) in human gut microbiota, so new information about this enzyme would certainly be of interest.

Strengths:

The cryo-EM structure for this enzyme is new and provides new insights into the function of the different protein domains, and a channel for formaldehyde between the two domains.

Weaknesses:

(1) The proposed catalytic mechanism in this manuscript does not make sense. Previous mechanistic studies on the Methylocella silvestris TMAO demethylase (FEBS Journal 2016, 283, 3979-3993, reference 7) reported that, as well as a Zn2+ cofactor, there was a dependence upon non-heme Fe2+, and proposed a catalytic mechanism involving deoxygenation to form TMA and an iron(IV)-oxo species, followed by oxidative demethylation to form DMA and formaldehyde.

In this work, the authors do not mention the previously proposed mechanism, but instead say that elemental analysis "excluded iron". This is alarming, since the previous work has a key role for non-heme iron in the mechanism. The elemental analysis here gives a Zn content of about 0.5 mol/mol protein (and no Fe), whereas the Methylocella TMAO demethylase was reported to contain 0.97 mol Zn/mol protein, and 0.35-0.38 mol Fe/mol protein. It does, therefore, appear that their enzyme is depleted in Zn, and the absence of Fe impacts the mechanism, as explained below.

The proposed catalytic mechanism in this manuscript, I am sorry to say, does not make sense to me, for several reasons:

(i) Demethylation to form formaldehyde is not a hydrolytic process; it is an oxidative process (normally accomplished by either cytochrome P450 or non-heme iron-dependent oxygenase). The authors propose that a zinc (II) hydroxide attacks the methyl group, which is unprecedented, and even if it were possible, would generate methanol, not formaldehyde.

(ii) The amine oxide is then proposed to deoxygenate, with hydroxide appearing on the Zn - unfortunately, amine oxide deoxygenation is a reductive process, for which a reducing agent is needed, and Zn2+ is not a redox-active metal ion;

(iii) The authors say "forming a tetrahedral intermediate, as described for metalloproteinase", but zinc metalloproteases attack an amide carbonyl to form an oxyanion intermediate, whereas in this mechanism, there is no carbonyl to attack, so this statement is just wrong.

So on several counts, the proposed mechanism cannot be correct. Some redox cofactor is needed in order to carry out amine oxide deoxygenation, and Zn2+cannot fulfil that role. Fe2+ could do, which is why the previously proposed mechanism involving an iron(IV)-oxo intermediate is feasible. But the authors claim that their enzyme has no Fe. If so, then there must be some other redox cofactor present. Therefore, the authors need to re-analyse their enzyme carefully and look either for Fe or for some other redox-active metal ion, and then provide convincing experimental evidence for a feasible catalytic mechanism. As it stands, the proposed catalytic mechanism is unacceptable.

We thank the reviewer for the detailed and thoughtful mechanistic critique. We fully agree that Zn2+ is not redox-active, and cannot directly mediate oxidative demethylation or amine oxide deoxygenation. We acknowledge that the oxidative step required for the conversion of TMAO to HCHO is not explicitly resolved in the present study. Accordingly, we have revised the manuscript to remove any implication of Zn2+-mediated redox chemistry, and have eliminated the previously imprecise analogy to zinc metalloproteases.

We recognize and now discuss prior biochemical work on TMAO demethylase from Methylocella silvestris (MsTDM), which proposed an iron-dependent oxidative mechanism (Zhu et al., FEBS 2016, 3979–3993). That study reported approximately one Zn2+ and one non-heme Fe2+ per active enzyme, implicated iron in catalysis through homology modeling and mutagenesis, and used crossover experiments suggesting a trimethylamine-like intermediate and oxygen transfer from TMAO, consistent with an Fe-dependent redox process. However, that system lacked experimental structural information, and did not define discrete metal-binding sites.

In contrast,

(1) Our high-resolution cryo-EM structures and metal analyses of TDM consistently reveal only a single, well-defined Zn2+-binding site, with no structural evidence for an additional iron-binding site as in the previous report (Zhu et al., FEBS 2016, 3979–3993).

(2) To investigate the potential involvement of iron, we expressed TDM in LB medium supplemented with Fe(NH4)2SO4 and determined its cryo-EM structure. This structure is identical to the original one, and no EM density corresponding to a second iron ion was observed. Moreover, the previously proposed Fe2+-binding residues are spatially distant (Figure S6).

(3) ICP-MS analysis shows undetectable Iron, and only Zinc ion (Figure S5).

(4) Our enzyme kinetics analysis with the TDM without Iron is comparable to that of from MsTDM (Figure 1A). The differences in Km and Vmax we propose is due to the difference in the overall sequence of the enzymes. Please also see comment at the end on a new published paper on MsTDM.

While we cannot comment on the MsTDM results, our ‘experimental’ results do not support the presence of an iron-binding site. Our data indicate that this chemistry is unlikely to be mediated by a canonical non-heme iron center as proposed for MsTDM. We therefore revised our model as a structural framework that rationalizes substrate binding, metal coordination, and product stabilization, while clearly delineating the limits of mechanistic inference supported by the current data.

The scheme 1 and proposal mechanism section were revised in page 4. Figure S6 was added.

(2) Given the metal content reported here, it is important to be able to compare the specific activity of the enzyme reported here with earlier preparations. The authors do quote a Vmax of 16.52 µM/min/mg; however, these are incorrect units for Vmax, they should be µmol/min/mg. There is a further inconsistency between the text saying µM/min/mg and the Figure saying µM/min/µg.

Thank you for the correction. We converted the Vmax unit to nmol/min/mg. and revised the text in page 2. We also compared with the value of the previous report in the TDM enzyme by revising the text on page 2. See also the note on a newly published manuscript and its comparison.

(3) The consumption of formaldehyde to form methylene-THF is potentially interesting, but the authors say "HCHO levels decreased in the presence of THF", which could potentially be due to enzyme inhibition by THF. Is there evidence that this is a time-dependent and protein-dependent reaction? Also in Figure 1C, HCHO reduction (%) is not very helpful, because we don't know what concentration of formaldehyde is formed under these conditions; it would be better to quote in units of concentration, rather than %.

We appreciate this important point. We have revised Figure 1C to present HCHO levels in absolute concentration units. While the current data demonstrate reduced detectable HCHO in the presence of THF, we agree that distinguishing between HCHO consumption and potential THF-mediated enzyme inhibition would require dedicated time-course and protein-dependence experiments. We have therefore revised the description to avoid overinterpretation and limit our conclusions to the observed changes in HCHO concentration in page 2, line 18-19.

(4) Has this particular TMAO demethylase been reported before? It's not clear which Paracoccus strain the enzyme is from; the Experimental Section just says "Paracoccus sp.", which is not very precise. There has been published work on the Paracoccus PS1 enzyme; is that the strain used? Details about the strain are needed, and the accession for the protein sequence.

Thank you for this comment. We now indicate that the enzyme is derived from Paracoccus sp. DMF and provide the accession number for the protein sequence (WP_263566861) in the Experimental Section (page 8, line 4).

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for the authors):

(1) The ITC experiment requires a ligand-into-buffer titration as an additional control. Also, maybe I misunderstood the molar ratio or the concentrations you used, but if you indeed added a total of 4.75 μL of 20 μM THF into 250 μL of 5 μM TDM, it is not clear to me how this leads to a final molar ratio of 3.

We thank the reviewer for this suggestion. A ligand-into-buffer control ITC experiment was performed and is now included in Figure S8C, which shows no realizable signal.

Regarding the molar ratio, it is our mistake. The experiment used 2.45 μL injections of 80 μM THF into 250 μL of 5 μM TDM. This corresponds to a final ligand concentration of ~12.8 μM, giving a ligand-to-protein molar ratio of ~2.6. We revised our text in page 9, ITC section.

(2) Characterization/quality check of all mutant enzymes should be performed by NanoDSF, CD spectroscopy or similar techniques to confirm that proteins are properly folded and fit for kinetic testing.

We appreciate the reviewer’s suggestion. All mutant proteins, including D220A, D367A, and F327A, were purified with yields similar to the wild-type enzyme. Additionally, cryo-EM maps of the mutants show well-defined density and overall structural integrity consistent with the wild-type. These findings indicate that the introduced mutations do not significantly affect protein folding, supporting their use for kinetic analysis. While NanoDSF might reveal differences in thermal stability due to mutations, it does not provide structural information. Our conclusions are not based on minor differences in thermostability. Our cryo-EM structures of the mutants offer much more reliable structural data than CD spectroscopy.

(3) Best practice would suggest overlapping pH ranges between different buffer systems in the pH-dependence experiments to rule out buffer-specific effects independent of pH.

We thank the reviewer for this helpful suggestion. We agree that overlapping pH ranges between different buffer systems can be valuable for excluding buffer-specific effects. In this study, the pH-dependence experiments were intended to provide a qualitative assessment of pH sensitivity rather than a detailed analysis of buffer-independent pKa values. While we cannot fully exclude minor buffer-specific contributions, the overall trends observed were reproducible and sufficient to support the conclusions drawn. We have added a clarifying statement to the revised manuscript to reflect this consideration, page 2, line 12.

(4) Structural comparison revealed high similarity to a THF-binding protein, with superposition onto a T protein.": It would be nice to show this as an additional figure, as resolution and occupancy for THF are low.

We thank the reviewer for this suggestion. To address this point, we have revised Figure S6 by adding an additional panel (C, now is Figure S7C) showing the structural superposition of TDM with the THF-binding T protein. This comparison is included to better illustrate the structural similarity, despite the limited resolution and partial occupancy of THF density in our map.

(5) Editing could have been done more thoroughly. Some spelling mistakes, e.g. "RESEULTS", "redius", "complec"; kinetic rate constants should be written in italic (not uniform between text and figures); Prism version is missing; Vmax of 16.52 µM/min/mg - doublecheck units; Figure S1B: The "arrow on the right" might have gone missing.

We corrected the spelling in page 2 ~ line 10, page 5 ~ line 34, page 6 ~ line40. Prism version was added. The arrow was added into figure S1B. The Vmax unit is corrected to nmol/min/mg.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

(1) The authors must re-examine the metal content of their purified enzyme, looking in particular for Fe or another redox-active metal ion, which could be involved in a reasonable catalytic mechanism.

We thank the reviewer for this suggestion and have carefully re-examined the metal content of TDM. Elemental analyses by EDX and ICP-MS consistently detected Zn2+ in purified TDM (Zn:protein ≈ 1:2), whereas Fe was below the detection limit across multiple independent preparations (Fig. S5A,B). To assess whether iron could be incorporated or play a functional role, we expressed TDM in E. coli grown in LB medium supplemented with Fe(NH4SO4)2 and performed activity assays in the presence of exogenous Fe2+. Neither condition resulted in enhanced enzymatic activity.

Consistent with these biochemical data, all cryo-EM structures reveal a single, well-defined metal-binding site coordinated by three conserved cysteine residues and occupied by Zn2+, with no evidence for an additional iron species or other redox-active metal site.

(2) The specific activity of the enzyme should be quoted in the same units as other literature papers, so that the enzyme activity can be compared. It could be, for example, that the content of Fe (or other redox-active metal) is low, and that could then give rise to a low specific activity.

Thank you for the suggestion, we quoted the enzyme units as similar with previous report. and revised the text in in page 2.

Since the submission of our paper a new report on MsTDM has been published (Cappa et al., Protein Science 33(11), e70364). It further supports our findings. First, the reported kinetic parameters using ITC (Vmax = 0.309 μmol/s, approximately 240 nmol/min/mg; Km = 0.866 mM) are comparable to our observed (156 nmol/min/mg and 1.33 mM, respectively) in the absence of exogenous iron. Second, the optimal pH for enzymatic activity similar to that observed in our paraTDM. Third, the reported two-state unfolding behavior is consistent with our cryo-EM structural observations, in which the more dynamic subunits appear to destabilize prior to unfolding of the core domains. Based on these findings, we now propose that Zn2+ appears to function primarily as an organizational cofactor at the core catalytic domain (revised Scheme 1).