Peer review process

Revised: This Reviewed Preprint has been revised by the authors in response to the previous round of peer review; the eLife assessment and the public reviews have been updated where necessary by the editors and peer reviewers.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorJiwon ShimSeoul National University of Science and Technology, Seoul, Republic of Korea

- Senior EditorUtpal BanerjeeUniversity of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, United States of America

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

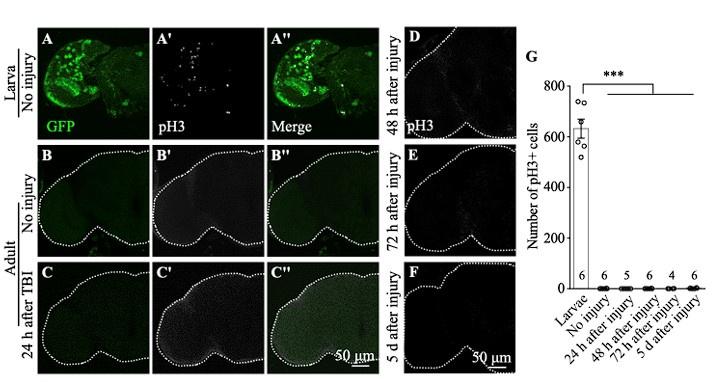

Li et al report that upon traumatic brain injury (TBI), Pvr signalling in astrocytes activates the JNK pathway and up-regulates the expression of the well-known JNK target MMP1. The FACS sort astrocytes, and carry out RNAseq analysis, which identifies pvr as well as genes of the JNK pathway as particularly up-regulated after TBI. They use conventional genetics loss of function, gain of function and epistasis analysis with and without TBI to verify the involvement of the JNK-MMP1 signalling pathway downstream of PVR. They also show that blocking endocytosis prolongs the involvement of this pathway in the TBI response.

The strengths are that multiple experiments are used to demonstrate that TBI in their hands damaged the BBB, induced apoptosis and increased MMP1 levels. The RNAseq analysis on FACS sorted astrocytes is nice and will be valuable to scientists beyond the confines of this paper. The functional genetic analysis is conventional, yet sound, and supports claims of JNK and MMP1 functioning downstream of Pvr in the TBI context.

For this revised version the authors have removed all the unsupported claims. This renders their remaining claims more solid. However, it has resulted in the loss of important cellular aspects of the response to TBI, limiting the scope and value of the work.

The main weakness is that novelty and insight are both rather limited. Others had previously published that both JNK signalling and MMP1 were activated upon injury, in multiple contexts (as well as the articles cited by the authors, they should also see Losada-Perez et al 2021). That Pvr can regulate JNK signalling was also known (Ishimaru et al 2004). The authors claim that the novelty was investigating injury responses in astrocytes in Drosophila. However, others had investigated injury responses by astrocytes in Drosophila before. It had been previously shown that astrocytes - defined as the Prospero+ neuropile glia, and also sharing evolutionary features with mammalian NG2 glia - respond to injury both in larval ventral nerve cords and in adult brains, where they proliferate regenerating glia and induce a neurogenic response (Kato et al 2011; Losada-Perez et al 2016; Harrison et al 2021; Simoes et al 2022). The authors argue that the novelty of the work is the investigation of the response of astrocytes to TBI. However, this is of somewhat limited scope. The authors mention that MMP1 regulates tissue remodelling, the inflammatory process and cancer. Exploring these functions further would have been an interesting addition, but the authors did not investigate what consequences the up-regulation of MMP1 after injury has in repair or regeneration processes.

The statistical analysis is incorrect in places, and this could affect the validity of some claims.

Altogether, this is an interesting and valuable addition to the repertoire of articles investigating neuron-glia communication and glial responses to injury in the Drosophila central nervous system (CNS). It is good and important to see this research area in Drosophila grow. This community together is building a compelling case for using Drosophila and its unparalleled powerful genetics to investigate nervous system injury, regeneration and repair, with important implications. Thus, this paper will be of interest to scientists investigating injury responses in the CNS using Drosophila, other model organisms (eg mice, fish) and humans.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In this study, authors used the Drosophila model to characterize molecular details underlying traumatic brain injury (TBI). Authors used the transcriptomic analysis of astrocytes collected by FACS sorting of cells derived from Drosophila heads following brain injury and identified upregulation of multiple genes, such as Pvr receptor, Jun, Fos, and MMP1. Additional studies identified that Pvr positively activates AP-1 transciption factor (TF) complex consisting of Jun and Fos, of which activation leads to the induction of MMP1. Finally, authors found that disruption of endocytosis and endocytotic trafficking facilitates Pvr signaling and subsequently leads to induction of AP-1 and MMP1.

Overall, this study provides important clues to understanding molecular mechanisms underlying TBI. The identified molecules linked to TBI in astrocytes could be potential targets for developing effective therapeutics. The obtained data from transcriptional profiling of astrocytes will be useful for future follow-up studies. The manuscript is well-organized and easy to read.

However, the connection suggested by the authors between Pvr and AP-1, potentially mediated through the JNK pathway, lacks strong experimental support in my view. It's important to recognize that AP-1 activity is influenced by multiple upstream signaling pathways, not just the JNK pathway, which is the most well-characterized among them. Therefore, assuming that AP-1 transcriptional activity solely reflects the activity of the JNK pathway without additional direct evidence is unwarranted. To strengthen their argument, the study could benefit from direct evidence implicating the JNK pathway in linking Pvr to AP-1. This could be achieved through genetic studies involving mutants or transgenes targeting key components of the JNK pathway, such as Bsk and Hep, the Drosophila homologues of JNK and JNKK, respectively. Alternatively, employing p-JNK antibody-based techniques like Western blotting, while considering the potential challenges associated with p-JNK immunohistochemistry, could provide further validation. This important criticism regarding the molecular link between Pvr and AP-1 has been overlooked.