Peer review process

Revised: This Reviewed Preprint has been revised by the authors in response to the previous round of peer review; the eLife assessment and the public reviews have been updated where necessary by the editors and peer reviewers.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorJun DingStanford University, Stanford, United States of America

- Senior EditorKate WassumUniversity of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, United States of America

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

In this study, Hoops et al. showed that Netrin-1 and UNC5c can guide dopaminergic innervation from nucleus accumbens to cortex during adolescence in rodent models. They found that these dopamine axons project to the prefrontal cortex in a Netrin-1 dependent manner and knocking down Netrin-1 disrupted motor and learning behaviors in mice. Furthermore, the authors used hamsters, a seasonal model that is affected by the length of daylight, to demonstrate that the guidance of dopamine axons is mediated by the environmental factor such as daytime length and in sex dependent manner.

Regarding the cell type specificity of Netrin-1 expression, the authors began by stating "this question is not the focus of the study and we consider it irrelevant to the main issue we are addressing, which is where in the forebrain regions we examined Netrin-1+ cells are present." This statement contradicts the exact issue regarding the specificity issue I raised. They then went on to show the RNAscope data for Netriin-1 in Figure 2, which showed Netrin-1 mRNA was actually expressed quite ubiquitously in anterior cingulate cortex, dorsopeduncular cortex, infralimbic cortex, prelimbic cortex, etc. In addition, contrary to the authors' statement that Netrin-1 is a "secreted protein", the confocal images in Figure 1 in the rebuttal letter actually show Netrin-1 present in "granule-like" organelles inside the cytoplasm of neurons. Finally, the authors presented Figure 7 to indicate the location where virus expressing Netrin-1 shRNA might be located. Again, the brain region targeted was quite focal and most likely did not cover all the Netrin-1+ brain regions in Figure 2. Collectively, these results raised more questions regarding the specificity of Netrin-1 expression in brain regions that are behaviorally relevant to this study.

With respect to the effectiveness of Netrin-1 knockdown in the animals in this study, the authors cited data in HEK293 cells (Figure 5), which did not include any statistics, and previously published in vivo data in a separate, independent study (Figure 6). They do not provide any data regarding the effectiveness of Netrin-1 knockdown in THIS study.

Similar concerns regarding UNC5C knockdown (points #6, #7, and #8) were not adequately addressed.

In brief, while this study provides a potential role of Netrin-1-UNC5C in target innervation of dopaminergic neurons and its behavioral output in risk-taking, the data lack sufficient evidence to firmly establish the cause-effect relationship.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

In this manuscript, Hoops et al., using two different model systems, identified key developmental changes in Netrin-1 and UNC5C signaling that correspond to behavioral changes and are sensitive to environmental factors that affect the timing of development. They found that Netrin-1 expression is highest in regions of the striatum and cortex where TH+ axons are travelling, and that knocking down Netrin-1 reduces TH+ varicosities in mPFC and reduces impulsive behaviors in a Go-No-Go test. Further, they show that the onset of Unc5 expression is sexually dimorphic in mice, and that in Siberian hamsters, environmental effects on development are also sexually dimorophic. This study addresses an important question using approaches that link molecular, circuit and behavioral changes. Understanding developmental trajectories of adolescence, and how they can be impacted by environmental factors, is an understudied area of neuroscience that is highly relevant to understanding the onset of mental health disorders. I appreciated the inclusion of replication cohorts within the study.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

This study from the Flores group aims at understanding neuronal circuit changes during adolescence which is an ill-defined, transitional period involving dramatic changes in behavior and anatomy. They focus on DA innervation of the prefrontal cortex, and their interaction with the guidance cue Netrin-1. They propose DA axons in the PFC increase in the postnatal period, and their density is reduced in a Netrin 1 knockdown, suggesting that Netrin abets the development of this mesocortical pathway. In such mice impulsivity gauged by a go-no go task is reduced. They then provide some evidence that Unc5c is developmentally regulated in DA axons. Finally they use an interesting hamster model, to study the effect of light hours on mesocortical innervation, and make some interesting observations about the timing of innervation and Unc5c expression, and the fact that females housed in winter day length conditions display an accelerated innervation of the prefrontal cortex.

Comments on the revision. Several points were addressed; some remain to be addressed.

#4. It's not clear to me that TH doesnt stain noradrenergic axons in the PFC. See Islam and Blaess, 2021, and references therein.

#6. The Netrin knockdown data provided is from a previous study/samples.

#8. While the authors make the argument that the behavior is linked to DA, they still haven't formally tested it, in my opinion.

#13. Fig 3, UNc 5c levels are not yet quantified. Furthermore, I agree with the previous reviewer that Unc5C knockdown would corroborate key aspects of the model.

New - Developmental trajectory of prefrontal TH-positive axons from early adolescence to adulthood is similar in male and female rats, (Willing Juraska et al., 2017). This needs discussion.

Author Response

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Public Comments

Reviewer 1

(1) Despite the well-established role of Netrin-1 and UNC5C axon guidance during embryonic commissural axons, it remains unclear which cell type(s) express Netrin-1 or UNC5C in the dopaminergic axons and their targets. For instance, the data in Figure 1F-G and Figure 2 are quite confusing. Does Netrin-1 or UNC5C express in all cell types or only dopamine-positive neurons in these two mouse models? It will also be important to provide quantitative assessments of UNC5C expression in dopaminergic axons at different ages.

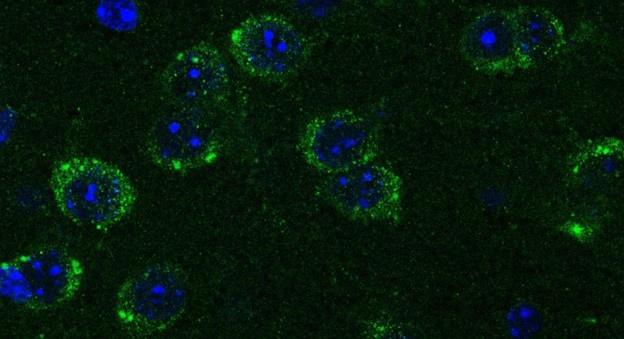

Netrin-1 is a secreted protein and in this manuscript we did not examine what cell types express Netrin-1. This question is not the focus of the study and we consider it irrelevant to the main issue we are addressing, which is where in the forebrain regions we examined Netrin-1+ cells are present. As per the reviewer’s request we include below images showing Netrin-1 protein and Netrin-1 mRNA expression in the forebrain. In Figure 1 below, we show a high magnification immunofluorescent image of a coronal forebrain section showing Netrin-1 protein expression.

Author response image 1.

This confocal microscope image shows immunofluorescent staining for Netrin-1 (green) localized around cell nuclei (stained by DAPI in blue). This image was taken from a coronal section of the lateral septum of an adult male mouse. Scale bar = 20µm

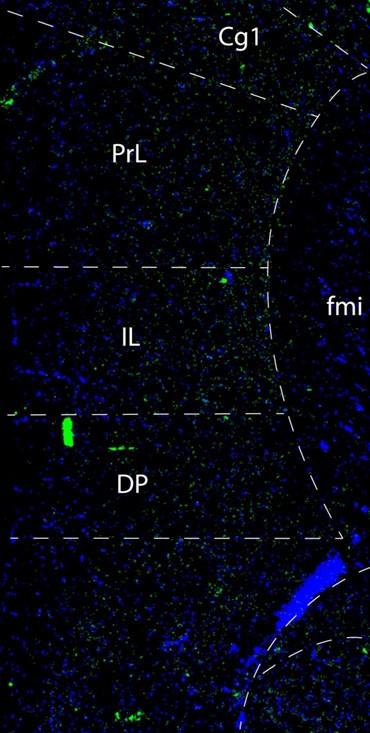

In Figures 2 and 3 below we show low and high magnification images from an RNAscope experiment confirming that cells in the forebrain regions examined express Netrin-1 mRNA.

Author response image 2.

This confocal microscope image of a coronal brain section of the medial prefrontal cortex of an adult male mouse shows Netrin-1 mRNA expression (green) and cell nuclei (DAPI, blue). Brain regions are as follows: Cg1: Anterior cingulate cortex 1, DP: dorsopeduncular cortex, fmi: forceps minor of the corpus callosum, IL: Infralimbic Cortex, PrL: Prelimbic Cortex

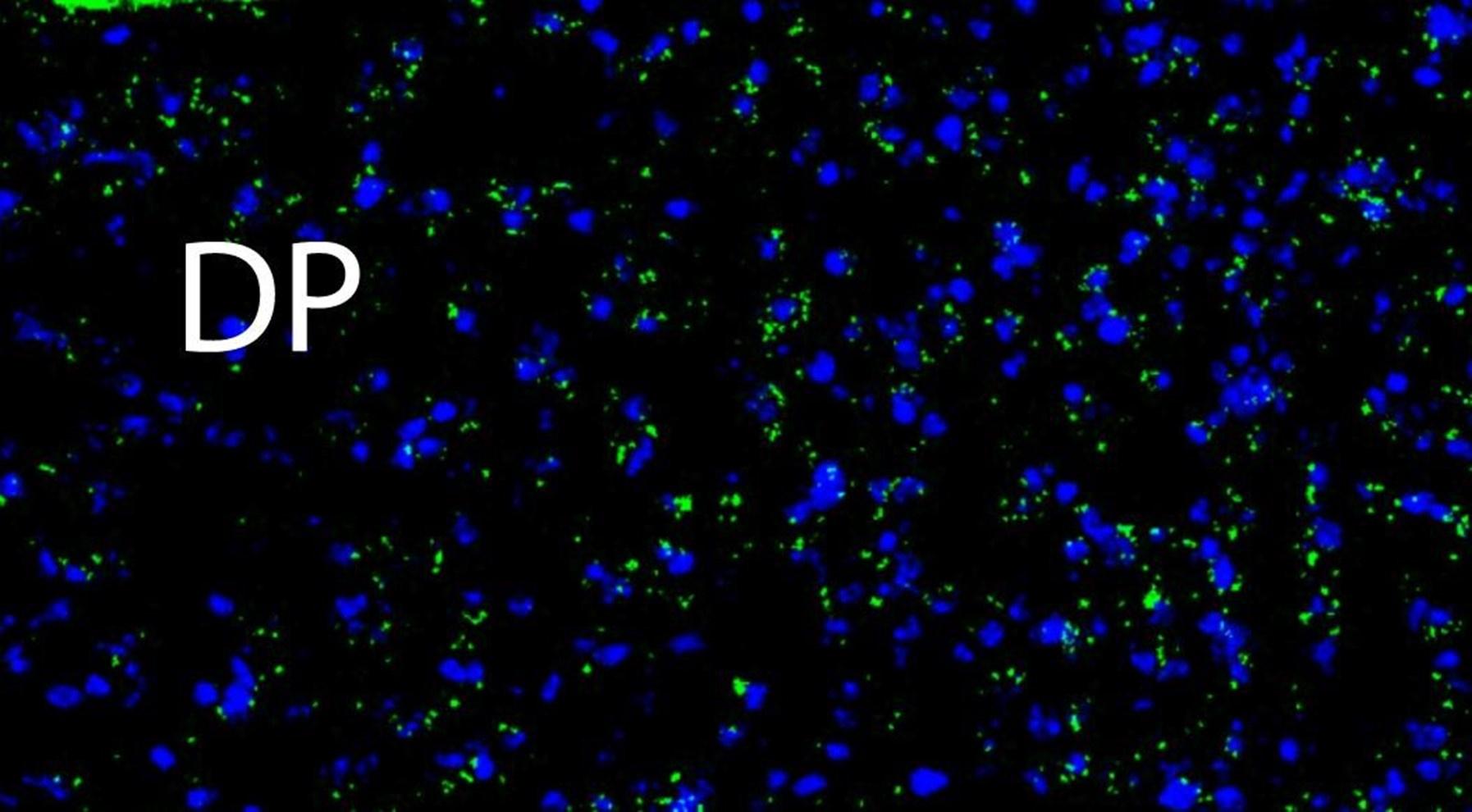

Author response image 3.

A higher resolution image from the same sample as in Figure 2 shows Netrin-1 mRNA (green) and cell nuclei (DAPI; blue). DP = dorsopeduncular cortex

Regarding UNC5c, this receptor homologue is expressed by dopamine neurons in the rodent ventral tegmental area (Daubaras et al., 2014; Manitt et al., 2010; Phillips et al., 2022). This does not preclude UNC5c expression in other cell types. UNC5c receptors are ubiquitously expressed in the brain throughout development, performing many different developmental functions (Kim and Ackerman, 2011; Murcia-Belmonte et al., 2019; Srivatsa et al., 2014). In this study we are interested in UNC5c expression by dopamine neurons, and particularly by their axons projecting to the nucleus accumbens. We therefore used immunofluorescent staining in the nucleus accumbens, showing UNC5 expression in TH+ axons. This work adds to the study by Manitt et al., 2010, which examined UNC5 expression in the VTA. Manitt et al. used Western blotting to demonstrate that UNC5 expression in VTA dopamine neurons increases during adolescence, as can be seen in the following figure:

References:

Daubaras M, Bo GD, Flores C. 2014. Target-dependent expression of the netrin-1 receptor, UNC5C, in projection neurons of the ventral tegmental area. Neuroscience 260:36–46. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.12.007

Kim D, Ackerman SL. 2011. The UNC5C Netrin Receptor Regulates Dorsal Guidance of Mouse Hindbrain Axons. J Neurosci 31:2167–2179. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.5254-10.20110.2011

Manitt C, Labelle-Dumais C, Eng C, Grant A, Mimee A, Stroh T, Flores C. 2010. Peri-Pubertal Emergence of UNC-5 Homologue Expression by Dopamine Neurons in Rodents. PLoS ONE 5:e11463-14. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011463

Murcia-Belmonte V, Coca Y, Vegar C, Negueruela S, Romero C de J, Valiño AJ, Sala S, DaSilva R, Kania A, Borrell V, Martinez LM, Erskine L, Herrera E. 2019. A Retino-retinal Projection Guided by Unc5c Emerged in Species with Retinal Waves. Current Biology 29:1149-1160.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.02.052

Phillips RA, Tuscher JJ, Black SL, Andraka E, Fitzgerald ND, Ianov L, Day JJ. 2022. An atlas of transcriptionally defined cell populations in the rat ventral tegmental area. Cell Reports 39:110616. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110616

Srivatsa S, Parthasarathy S, Britanova O, Bormuth I, Donahoo A-L, Ackerman SL, Richards LJ, Tarabykin V. 2014. Unc5C and DCC act downstream of Ctip2 and Satb2 and contribute to corpus callosum formation. Nat Commun 5:3708. doi:10.1038/ncomms4708

(2) Figure 1 used shRNA to knockdown Netrin-1 in the Septum and these mice were subjected to behavioral testing. These results, again, are not supported by any valid data that the knockdown approach actually worked in dopaminergic axons. It is also unclear whether knocking down Netrin-1 in the septum will re-route dopaminergic axons or lead to cell death in the dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta?

First we want to clarify and emphasize, that our knockdown approach was not designed to knock down Netrin-1 in dopamine neurons or their axons. Our goal was to knock down Netrin-1 expression in cells expressing this guidance cue gene in the dorsal peduncular cortex.

We have previously established the efficacy of the shRNA Netrin-1 knockdown virus used in this experiment for reducing the expression of Netrin-1 (Cuesta et al., 2020). The shRNA reduces Netrin-1 levels in vitro and in vivo.

We agree that our experiments do not address the fate of the dopamine axons that are misrouted away from the medial prefrontal cortex. This research is ongoing, and we have now added a note regarding this to our manuscript.

Our current hypothesis, based on experiments being conducted as part of another line of research in the lab, is that these axons are rerouted to a different brain region which they then ectopically innervate. In these experiments we are finding that male mice exposed to tetrahydrocannabinol in adolescence show reduced dopamine innervation in the medial prefrontal cortex in adulthood but increased dopamine input in the orbitofrontal cortex. In addition, these mice show increased action impulsivity in the Go/No-Go task in adulthood (Capolicchio et al., Society for Neuroscience 2023 Abstracts)

References:

Capolicchio T., Hernandez, G., Dube, E., Estrada, K., Giroux, M., Flores, C. (2023) Divergent outcomes of delta 9 - tetrahydrocannabinol in adolescence on dopamine and cognitive development in male and female mice. Society for Neuroscience, Washington, DC, United States [abstract].

Cuesta S, Nouel D, Reynolds LM, Morgunova A, Torres-Berrío A, White A, Hernandez G, Cooper HM, Flores C. 2020. Dopamine Axon Targeting in the Nucleus Accumbens in Adolescence Requires Netrin-1. Frontiers Cell Dev Biology 8:487. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.00487

(3) Another issue with Figure1J. It is unclear whether the viruses were injected into a WT mouse model or into a Cre-mouse model driven by a promoter specifically expresses in dorsal peduncular cortex? The authors should provide evidence that Netrin-1 mRNA and proteins are indeed significantly reduced. The authors should address the anatomic results of the area of virus diffusion to confirm the virus specifically infected the cells in dorsal peduncular cortex.

All the virus knockdown experiments were conducted in wild type mice, we added this information to Figure 1k.

The efficacy of the shRNA in knocking down Netrin-1 was demonstrated by Cuesta et al. (2020) both in vitro and in vivo, as we show in our response to the reviewer’s previous comment above.

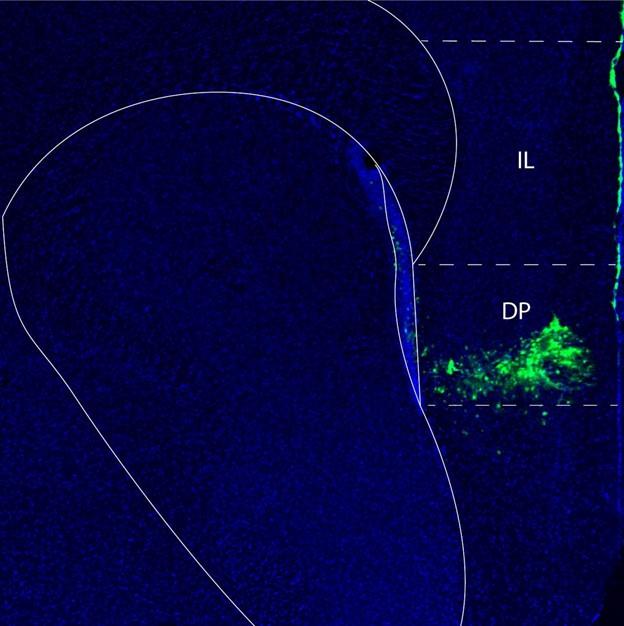

We also now provide anatomical images demonstrating the localization of the injection and area of virus diffusion in the mouse forebrain. In Author response image 4 below the area of virus diffusion is visible as green fluorescent signal.

Author response image 4.

Fluorescent microscopy image of a mouse forebrain demonstrating the localization of the injection of a virus to knock down Netrin-1. The location of the virus is in green, while cell nuclei are in blue (DAPI). Abbreviations: DP: dorsopeduncular cortex IL: infralimbic cortex

References:

Cuesta S, Nouel D, Reynolds LM, Morgunova A, Torres-Berrío A, White A, Hernandez G, Cooper HM, Flores C. 2020. Dopamine Axon Targeting in the Nucleus Accumbens in Adolescence Requires Netrin-1. Frontiers Cell Dev Biology 8:487. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.00487

(4) The authors need to provide information regarding the efficiency and duration of knocking down. For instance, in Figure 1K, the mice were tested after 53 days post injection, can the virus activity in the brain last for such a long time?

In our study we are interested in the role of Netrin-1 expression in the guidance of dopamine axons from the nucleus accumbens to the medial prefrontal cortex. The critical window for these axons leaving the nucleus accumbens and growing to the cortex is early adolescence (Reynolds et al., 2018b). This is why we injected the virus at the onset of adolescence, at postnatal day 21. As dopamine axons grow from the nucleus accumbens to the prefrontal cortex, they pass through the dorsal peduncular cortex. We disrupted Netrin-1 expression at this point along their route to determine whether it is the Netrin-1 present along their route that guides these axons to the prefrontal cortex. We hypothesized that the shRNA Netrin-1 virus would disrupt the growth of the dopamine axons, reducing the number of axons that reach the prefrontal cortex and therefore the number of axons that innervate this region in adulthood.

We conducted our behavioural tests during adulthood, after the critical window during which dopamine axon growth occurs, so as to observe the enduring behavioral consequences of this misrouting. This experimental approach is designed for the shRNa Netrin-1 virus to be expressed in cells in the dorsopeduncular cortex when the dopamine axons are growing, during adolescence.

References:

Capolicchio T., Hernandez, G., Dube, E., Estrada, K., Giroux, M., Flores, C. (2023) Divergent outcomes of delta 9 - tetrahydrocannabinol in adolescence on dopamine and cognitive development in male and female mice. Society for Neuroscience, Washington, DC, United States [abstract].

Reynolds LM, Yetnikoff L, Pokinko M, Wodzinski M, Epelbaum JG, Lambert LC, Cossette M-P, Arvanitogiannis A, Flores C. 2018b. Early Adolescence is a Critical Period for the Maturation of Inhibitory Behavior. Cerebral cortex 29:3676–3686. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhy247

(5) In Figure 1N-Q, silencing Netrin-1 results in less DA axons targeting to infralimbic cortex, but why the Netrin-1 knocking down mice revealed the improved behavior?

This is indeed an intriguing finding, and we have now added a mention of it to our manuscript. We have demonstrated that misrouting dopamine axons away from the medial prefrontal cortex during adolescence alters behaviour, but why this improves their action impulsivity ability is something currently unknown to us. One potential answer is that the dopamine axons are misrouted to a different brain region that is also involved in controlling impulsive behaviour, perhaps the dorsal striatum (Kim and Im, 2019) or the orbital prefrontal cortex (Jonker et al., 2015).

We would also like to note that we are finding that other manipulations that appear to reroute dopamine axons to unintended targets can lead to reduced action impulsivity as measured using the Go No Go task. As we mentioned above, current experiments in the lab, which are part of a different line of research, are showing that male mice exposed to tetrahydrocannabinol in adolescence show reduced dopamine innervation in the medial prefrontal cortex in adulthood, but increased dopamine input in the orbitofrontal cortex. In addition, these mice show increased action impulsivity in the Go/No-Go task in adulthood (Capolicchio et al., Society for Neuroscience 2023 Abstracts)

References

Capolicchio T., Hernandez, G., Dube, E., Estrada, K., Giroux, M., Flores, C. (2023) Divergent outcomes of delta 9 - tetrahydrocannabinol in adolescence on dopamine and cognitive development in male and female mice. Society for Neuroscience, Washington, DC, United States [abstract].

Jonker FA, Jonker C, Scheltens P, Scherder EJA. 2015. The role of the orbitofrontal cortex in cognition and behavior. Rev Neurosci 26:1–11. doi:10.1515/revneuro2014-0043 Kim B, Im H. 2019. The role of the dorsal striatum in choice impulsivity. Ann N York Acad Sci 1451:92–111. doi:10.1111/nyas.13961

(6) What is the effect of knocking down UNC5C on dopamine axons guidance to the cortex?

We have found that mice that are heterozygous for a nonsense Unc5c mutation, and as a result have reduced levels of UNC5c protein, show reduced amphetamine-induced locomotion and stereotypy (Auger et al., 2013). In the same manuscript we show that this effect only emerges during adolescence, in concert with the growth of dopamine axons to the prefrontal cortex. This is indirect but strong evidence that UNC5c receptors are necessary for correct adolescent dopamine axon development.

References

Auger ML, Schmidt ERE, Manitt C, Dal-Bo G, Pasterkamp RJ, Flores C. 2013. unc5c haploinsufficient phenotype: striking similarities with the dcc haploinsufficiency model. European Journal of Neuroscience 38:2853–2863. doi:10.1111/ejn.12270

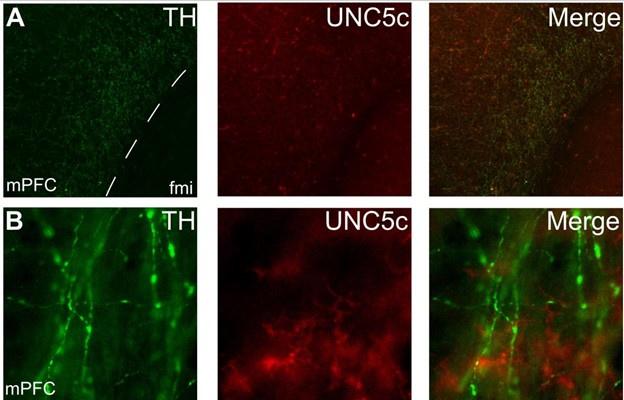

(7) In Figures 2-4, the authors only showed the amount of DA axons and UNC5C in NAcc. However, it remains unclear whether these experiments also impact the projections of dopaminergic axons to other brain regions, critical for the behavioral phenotypes. What about other brain regions such as prefrontal cortex? Do the projection of DA axons and UNC5c level in cortex have similar pattern to those in NAcc?

UNC5c receptors are expressed throughout development and are involved in many developmental processes (Kim and Ackerman, 2011; Murcia-Belmonte et al., 2019; Srivatsa et al., 2014). We cannot say whether the pattern we observe here is unique to the nucleus accumbens, but it is certainly not universal throughout the brain.

The brain region we focus on in our manuscript, in addition to the nucleus accumbens, is the medial prefrontal cortex. Close and thorough examination of the prefrontal cortices of adult mice revealed practically no UNC5c expression by dopamine axons. However, we did observe very rare cases of dopamine axons expressing UNC5c. It is not clear whether these rare cases are present before or during adolescence.

Below is a representative set of images of this observation, which is now also included as Supplementary Figure 4:

Author response image 5.

Expression of UNC5c protein in the medial prefrontal cortex of an adult male mouse. Low (A) and high (B) magnification images demonstrate that there is little UNC5c expression in dopamine axons in the medial prefrontal cortex. Here we identify dopamine axons by immunofluorescent staining for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, see our response to comment #9 regarding the specificity of the TH antibody for dopamine axons in the prefrontal cortex). This figure is also included as Supplementary Figure 4 in the manuscript. Abbreviations: fmi: forceps minor of the corpus callosum, mPFC: medial prefrontal cortex.

References:

Kim D, Ackerman SL. 2011. The UNC5C Netrin Receptor Regulates Dorsal Guidance of Mouse Hindbrain Axons. J Neurosci 31:2167–2179. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.5254- 10.20110.2011

Murcia-Belmonte V, Coca Y, Vegar C, Negueruela S, Romero C de J, Valiño AJ, Sala S, DaSilva R, Kania A, Borrell V, Martinez LM, Erskine L, Herrera E. 2019. A Retino-retinal Projection Guided by Unc5c Emerged in Species with Retinal Waves. Current Biology 29:1149-1160.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.02.052

Srivatsa S, Parthasarathy S, Britanova O, Bormuth I, Donahoo A-L, Ackerman SL, Richards LJ, Tarabykin V. 2014. Unc5C and DCC act downstream of Ctip2 and Satb2 and contribute to corpus callosum formation. Nat Commun 5:3708. doi:10.1038/ncomms4708

(8) Can overexpression of UNC5c or Netrin-1 in male winter hamsters mimic the observations in summer hamsters? Or overexpression of UNC5c in female summer hamsters to mimic the winter hamster? This would be helpful to confirm the causal role of UNC5C in guiding DA axons during adolescence.

This is an excellent question. We are very interested in both increasing and decreasing UNC5c expression in hamster dopamine axons to see if we can directly manipulate summer hamsters into winter hamsters and vice versa. We are currently exploring virus-based approaches to design these experiments and are excited for results in this area.

(9) The entire study relied on using tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) as a marker for dopaminergic axons. However, the expression of TH (either by IHC or IF) can be influenced by other environmental factors, that could alter the expression of TH at the cellular level.

This is an excellent point that we now carefully address in our methods by adding the following:

In this study we pay great attention to the morphology and localization of the fibres from which we quantify varicosities to avoid counting any fibres stained with TH antibodies that are not dopamine fibres. The fibres that we examine and that are labelled by the TH antibody show features indistinguishable from the classic features of cortical dopamine axons in rodents (Berger et al., 1974; 1983; Van Eden et al., 1987; Manitt et al., 2011), namely they are thin fibres with irregularly-spaced varicosities, are densely packed in the nucleus accumbens, sparsely present only in the deep layers of the prefrontal cortex, and are not regularly oriented in relation to the pial surface. This is in contrast to rodent norepinephrine fibres, which are smooth or beaded in appearance, relatively thick with regularly spaced varicosities, increase in density towards the shallow cortical layers, and are in large part oriented either parallel or perpendicular to the pial surface (Berger et al., 1974; Levitt and Moore, 1979; Berger et al., 1983; Miner et al., 2003). Furthermore, previous studies in rodents have noted that only norepinephrine cell bodies are detectable using immunofluorescence for TH, not norepinephrine processes (Pickel et al., 1975; Verney et al., 1982; Miner et al., 2003), and we did not observe any norepinephrine-like fibres.

Furthermore, we are not aware of any other processes in the forebrain that are known to be immunopositive for TH under any environmental conditions.

To reduce confusion, we have replaced the abbreviation for dopamine – DA – with TH in the relevant panels in Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4 to clarify exactly what is represented in these images. As can be seen in these images, fluorescent green labelling is present only in axons, which is to be expected of dopamine labelling in these forebrain regions.

References:

Berger B, Tassin JP, Blanc G, Moyne MA, Thierry AM (1974) Histochemical confirmation for dopaminergic innervation of the rat cerebral cortex after destruction of the noradrenergic ascending pathways. Brain Res 81:332–337.

Berger B, Verney C, Gay M, Vigny A (1983) Immunocytochemical Characterization of the Dopaminergic and Noradrenergic Innervation of the Rat Neocortex During Early Ontogeny. In: Proceedings of the 9th Meeting of the International Neurobiology Society, pp 263–267 Progress in Brain Research. Elsevier.

Levitt P, Moore RY (1979) Development of the noradrenergic innervation of neocortex. Brain Res 162:243–259.

Manitt C, Mimee A, Eng C, Pokinko M, Stroh T, Cooper HM, Kolb B, Flores C (2011) The Netrin Receptor DCC Is Required in the Pubertal Organization of Mesocortical Dopamine Circuitry. J Neurosci 31:8381–8394.

Miner LH, Schroeter S, Blakely RD, Sesack SR (2003) Ultrastructural localization of the norepinephrine transporter in superficial and deep layers of the rat prelimbic prefrontal cortex and its spatial relationship to probable dopamine terminals. J Comp Neurol 466:478–494.

Pickel VM, Joh TH, Field PM, Becker CG, Reis DJ (1975) Cellular localization of tyrosine hydroxylase by immunohistochemistry. J Histochem Cytochem 23:1–12.

Van Eden CG, Hoorneman EM, Buijs RM, Matthijssen MA, Geffard M, Uylings HBM (1987) Immunocytochemical localization of dopamine in the prefrontal cortex of the rat at the light and electron microscopical level. Neurosci 22:849–862.

Verney C, Berger B, Adrien J, Vigny A, Gay M (1982) Development of the dopaminergic innervation of the rat cerebral cortex. A light microscopic immunocytochemical study using anti-tyrosine hydroxylase antibodies. Dev Brain Res 5:41–52.

(10) Are Netrin-1/UNC5C the only signal guiding dopamine axon during adolescence? Are there other neuronal circuits involved in this process?

Our intention for this study was to examine the role of Netrin-1 and its receptor UNC5C specifically, but we do not suggest that they are the only molecules to play a role. The process of guiding growing dopamine axons during adolescence is likely complex and we expect other guidance mechanisms to also be involved. From our previous work we know that the Netrin-1 receptor DCC is critical in this process (Hoops and Flores, 2017; Reynolds et al., 2023). Several other molecules have been identified in Netrin-1/DCC signaling processes that control corpus callosum development and there is every possibility that the same or similar molecules may be important in guiding dopamine axons (Schlienger et al., 2023).

References:

Hoops D, Flores C. 2017. Making Dopamine Connections in Adolescence. Trends in Neurosciences 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2017.09.004

Reynolds LM, Hernandez G, MacGowan D, Popescu C, Nouel D, Cuesta S, Burke S, Savell KE, Zhao J, Restrepo-Lozano JM, Giroux M, Israel S, Orsini T, He S, Wodzinski M, Avramescu RG, Pokinko M, Epelbaum JG, Niu Z, Pantoja-Urbán AH, Trudeau L-É, Kolb B, Day JJ, Flores C. 2023. Amphetamine disrupts dopamine axon growth in adolescence by a sex-specific mechanism in mice. Nat Commun 14:4035. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-39665-1

Schlienger S, Yam PT, Balekoglu N, Ducuing H, Michaud J-F, Makihara S, Kramer DK, Chen B, Fasano A, Berardelli A, Hamdan FF, Rouleau GA, Srour M, Charron F. 2023. Genetics of mirror movements identifies a multifunctional complex required for Netrin-1 guidance and lateralization of motor control. Sci Adv 9:eadd5501. doi:10.1126/sciadv.add5501

(11) Finally, despite the authors' claim that the dopaminergic axon project is sensitive to the duration of daylight in the hamster, they never provided definitive evidence to support this hypothesis.

By “definitive evidence” we think that the reviewer is requesting a single statistical model including measures from both the summer and winter groups. Such a model would provide a probability estimate of whether dopamine axon growth is sensitive to daylight duration. Therefore, we ran these models, one for male hamsters and one for female hamsters.

In both sexes we find a significant effect of daylength on dopamine innervation, interacting with age. Male age by daylength interaction: F = 6.383, p = 0.00242. Female age by daylength interaction: F = 21.872, p = 1.97 x 10-9. The full statistical analysis is available as a supplement to this letter (Response_Letter_Stats_Details.docx).

Reviewer 3

(1) Fig 1 A and B don't appear to be the same section level.

The reviewer is correct that Fig 1B is anterior to Fig 1A. We have changed Figure 1A to match the section level of Figure 1B.

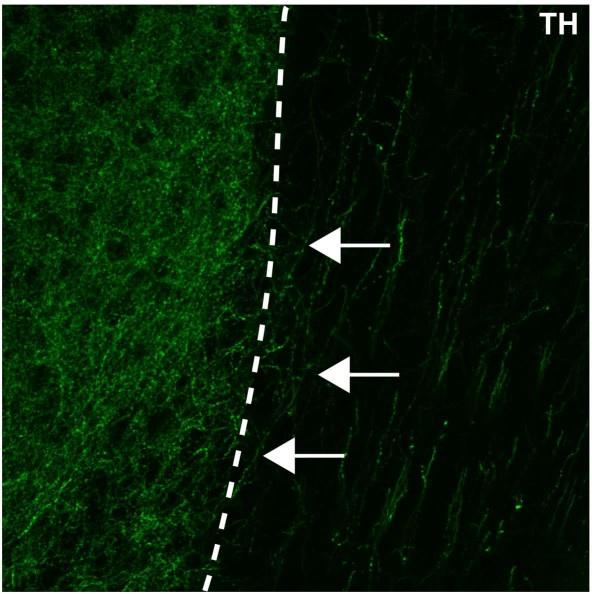

(2) Fig 1C. It is not clear that these axons are crossing from the shell of the NAC.

We have added a dashed line to Figure 1C to highlight the boundary of the nucleus accumbens, which hopefully emphasizes that there are fibres crossing the boundary. We also include here an enlarged image of this panel:

Author response image 6.

An enlarged image of Figure1c in the manuscript. The nucleus accumbens (left of the dotted line) is densely packed with TH+ axons (in green). Some of these TH+ axons can be observed extending from the nucleus accumbens medially towards a region containing dorsally oriented TH+ fibres (white arrows).

(3) Fig 1. Measuring width of the bundle is an odd way to measure DA axon numbers. First the width could be changing during adult for various reasons including change in brain size. Second, I wouldn't consider these axons in a traditional bundle. Third, could DA axon counts be provided, rather than these proxy measures.

With regards to potential changes in brain size, we agree that this could have potentially explained the increased width of the dopamine axon pathway. That is why it was important for us to use stereology to measure the density of dopamine axons within the pathway. If the width increased but no new axons grew along the pathway, we would have seen a decrease in axon density from adolescence to adulthood. Instead, our results show that the density of axons remained constant.

We agree with the reviewer that the dopamine axons do not form a traditional “bundle”. Therefore, throughout the manuscript we now avoid using the term bundle.

Although we cannot count every single axon, an accurate estimate of this number can be obtained using stereology, an unbiassed method for efficiently quantifying large, irregularly distributed objects. We used stereology to count TH+ axons in an unbiased subset of the total area occupied by these axons. Unbiased stereology is the gold-standard technique for estimating populations of anatomical objects, such as axons, that are so numerous that it would be impractical or impossible to measure every single one. Here and elsewhere we generally provide results as densities and areas of occupancy (Reynolds et al., 2022). To avoid confusion, we now clarify that we are counting the width of the area that dopamine axons occupy (rather than the dopamine axon “bundle”).

References:

Reynolds LM, Pantoja-Urbán AH, MacGowan D, Manitt C, Nouel D, Flores C. 2022. Dopaminergic System Function and Dysfunction: Experimental Approaches. Neuromethods 31–63. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-2799-0_2

(4) TH in the cortex could also be of noradrenergic origin. This needs to be ruled out to score DA axons

This is the same comment as Reviewer 1 #9. Please see our response below, which we have also added to our methods:

In this study we pay great attention to the morphology and localization of the fibres from which we quantify varicosities to avoid counting any fibres stained with TH antibodies that are not dopamine fibres. The fibres that we examine and that are labelled by the TH antibody show features indistinguishable from the classic features of cortical dopamine axons in rodents (Berger et al., 1974; 1983; Van Eden et al., 1987; Manitt et al., 2011), namely they are thin fibres with irregularly-spaced varicosities, are densely packed in the nucleus accumbens, sparsely present only in the deep layers of the prefrontal cortex, and are not regularly oriented in relation to the pial surface. This is in contrast to rodent norepinephrine fibres, which are smooth or beaded in appearance, relatively thick with regularly spaced varicosities, increase in density towards the shallow cortical layers, and are in large part oriented either parallel or perpendicular to the pial surface (Berger et al., 1974; Levitt and Moore, 1979; Berger et al., 1983; Miner et al., 2003). Furthermore, previous studies in rodents have noted that only norepinephrine cell bodies are detectable using immunofluorescence for TH, not norepinephrine processes (Pickel et al., 1975; Verney et al., 1982; Miner et al., 2003), and we did not observe any norepinephrine-like fibres.

References:

Berger B, Tassin JP, Blanc G, Moyne MA, Thierry AM (1974) Histochemical confirmation for dopaminergic innervation of the rat cerebral cortex after destruction of the noradrenergic ascending pathways. Brain Res 81:332–337.

Berger B, Verney C, Gay M, Vigny A (1983) Immunocytochemical Characterization of the Dopaminergic and Noradrenergic Innervation of the Rat Neocortex During Early Ontogeny. In: Proceedings of the 9th Meeting of the International Neurobiology Society, pp 263–267 Progress in Brain Research. Elsevier.

Levitt P, Moore RY (1979) Development of the noradrenergic innervation of neocortex. Brain Res 162:243–259.

Manitt C, Mimee A, Eng C, Pokinko M, Stroh T, Cooper HM, Kolb B, Flores C (2011) The Netrin Receptor DCC Is Required in the Pubertal Organization of Mesocortical Dopamine Circuitry. J Neurosci 31:8381–8394.

Miner LH, Schroeter S, Blakely RD, Sesack SR (2003) Ultrastructural localization of the norepinephrine transporter in superficial and deep layers of the rat prelimbic prefrontal cortex and its spatial relationship to probable dopamine terminals. J Comp Neurol 466:478–494.

Pickel VM, Joh TH, Field PM, Becker CG, Reis DJ (1975) Cellular localization of tyrosine hydroxylase by immunohistochemistry. J Histochem Cytochem 23:1–12.

Van Eden CG, Hoorneman EM, Buijs RM, Matthijssen MA, Geffard M, Uylings HBM (1987) Immunocytochemical localization of dopamine in the prefrontal cortex of the rat at the light and electron microscopical level. Neurosci 22:849–862.

Verney C, Berger B, Adrien J, Vigny A, Gay M (1982) Development of the dopaminergic innervation of the rat cerebral cortex. A light microscopic immunocytochemical study using anti-tyrosine hydroxylase antibodies. Dev Brain Res 5:41–52.

(5) Netrin staining should be provided with NeuN + DAPI; its not clear these are all cell bodies. An in situ of Netrin would help as well.

A similar comment was raised by Reviewer 1 in point #1. Please see below the immunofluorescent and RNA scope images showing expression of Netrin-1 protein and mRNA in the forebrain.

Author response image 7.

This confocal microscope image shows immunofluorescent staining for Netrin-1 (green) localized around cell nuclei (stained by DAPI in blue). This image was taken from a coronal section of the lateral septum of an adult male mouse. Scale bar = 20µm

Author response image 8.

This confocal microscope image of a coronal brain section of the medial prefrontal cortex of an adult male mouse shows Netrin-1 mRNA expression (green) and cell nuclei (DAPI, blue). RNAscope was used to generate this image. Brain regions are as follows: Cg1: Anterior cingulate cortex 1, DP: dorsopeduncular cortex, IL: Infralimbic Cortex, PrL: Prelimbic Cortex, fmi: forceps minor of the corpus callosum

Author response image 9.

A higher resolution image from the same sample as in Figure 2 shows Netrin-1 mRNA (green) and cell nuclei (DAPI; blue). DP = dorsopeduncular cortex

(6) The Netrin knockdown needs validation. How strong was the knockdown etc?

This comment was also raised by Reviewer 1 #1.

We have previously established the efficacy of the shRNA Netrin-1 knockdown virus used in this experiment for reducing the expression of Netrin-1 (Cuesta et al., 2020). The shRNA reduces Netrin-1 levels in vitro and in vivo.

References:

Cuesta S, Nouel D, Reynolds LM, Morgunova A, Torres-Berrío A, White A, Hernandez G, Cooper HM, Flores C. 2020. Dopamine Axon Targeting in the Nucleus Accumbens in Adolescence Requires Netrin-1. Frontiers Cell Dev Biology 8:487. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.00487

(7) If the conclusion that knocking down Netrin in cortex decreases DA innervation of the IL, how can that be reconciled with Netrin-Unc repulsion.

This is an intriguing question and one that we are in the planning stages of addressing with new experiments.

Although we do not have a mechanistic answered for how a repulsive receptor helps guide these axons, we would like to note that previous indirect evidence from a study by our group also suggests that reducing UNC5c signaling in dopamine axons in adolescence increases dopamine innervation to the prefrontal cortex (Auger et al, 2013).

References

Auger ML, Schmidt ERE, Manitt C, Dal-Bo G, Pasterkamp RJ, Flores C. 2013. unc5c haploinsufficient phenotype: striking similarities with the dcc haploinsufficiency model. European Journal of Neuroscience 38:2853–2863. doi:10.1111/ejn.12270

(8) The behavioral phenotype in Fig 1 is interesting, but its not clear if its related to DA axons/signaling. IN general, no evidence in this paper is provided for the role of DA in the adolescent behaviors described.

We agree with the reviewer that the behaviours we describe in adult mice are complex and are likely to involve several neurotransmitter systems. However, there is ample evidence for the role of dopamine signaling in cognitive control behaviours (Bari and Robbins, 2013; Eagle et al., 2008; Ott et al., 2023) and our published work has shown that alterations in the growth of dopamine axons to the prefrontal cortex leads to changes in impulse control as measured via the Go/No-Go task in adulthood (Reynolds et al., 2023, 2018a; Vassilev et al., 2021).

The other adolescent behaviour we examined was risk-like taking behaviour in male and female hamsters (Figures 4 and 5), as a means of characterizing maturation in this behavior over time. We decided not to use the Go/No-Go task because as far as we know, this has never been employed in Siberian Hamsters and it will be difficult to implement. Instead, we chose the light/dark box paradigm, which requires no training and is ideal for charting behavioural changes over short time periods. Indeed, risk-like taking behavior in rodents and in humans changes from adolescence to adulthood paralleling changes in prefrontal cortex development, including the gradual input of dopamine axons to this region.

References:

Bari A, Robbins TW. 2013. Inhibition and impulsivity: Behavioral and neural basis of response control. Progress in neurobiology 108:44–79. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.06.005

Eagle DM, Bari A, Robbins TW. 2008. The neuropsychopharmacology of action inhibition: cross-species translation of the stop-signal and go/no-go tasks. Psychopharmacology 199:439–456. doi:10.1007/s00213-008-1127-6

Ott T, Stein AM, Nieder A. 2023. Dopamine receptor activation regulates reward expectancy signals during cognitive control in primate prefrontal neurons. Nat Commun 14:7537. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-43271-6

Reynolds LM, Hernandez G, MacGowan D, Popescu C, Nouel D, Cuesta S, Burke S, Savell KE, Zhao J, Restrepo-Lozano JM, Giroux M, Israel S, Orsini T, He S, Wodzinski M, Avramescu RG, Pokinko M, Epelbaum JG, Niu Z, Pantoja-Urbán AH, Trudeau L-É, Kolb B, Day JJ, Flores C. 2023. Amphetamine disrupts dopamine axon growth in adolescence by a sex-specific mechanism in mice. Nat Commun 14:4035. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-39665-1

Reynolds LM, Pokinko M, Torres-Berrío A, Cuesta S, Lambert LC, Pellitero EDC, Wodzinski M, Manitt C, Krimpenfort P, Kolb B, Flores C. 2018a. DCC Receptors Drive Prefrontal Cortex Maturation by Determining Dopamine Axon Targeting in Adolescence. Biological psychiatry 83:181–192. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.06.009

Vassilev P, Pantoja-Urban AH, Giroux M, Nouel D, Hernandez G, Orsini T, Flores C. 2021. Unique effects of social defeat stress in adolescent male mice on the Netrin-1/DCC pathway, prefrontal cortex dopamine and cognition (Social stress in adolescent vs. adult male mice). Eneuro ENEURO.0045-21.2021. doi:10.1523/eneuro.0045-21.2021

(9) Fig2 - boxes should be drawn on the NAc diagram to indicate sampled regions. Some quantification of Unc5c would be useful. Also, some validation of the Unc5c antibody would be nice.

The images presented were taken medial to the anterior commissure and we have edited Figure 2 to show this. However, we did not notice any intra-accumbens variation, including between the core and the shell. Therefore, the images are representative of what was observed throughout the entire nucleus accumbens.

To quantify UNC5c in the accumbens we conducted a Western blot experiment in male mice at different ages. A one-way ANOVA analyzing band intensity (relative to the 15-day-old average band intensity) as the response variable and age as the predictor variable showed a significant effect of age (F=5.615, p=0.01). Posthoc analysis revealed that 15-day-old mice have less UNC5c in the nucleus accumbens compared to 21- and 35-day-old mice.

Author response image 10.

The graph depicts the results of a Western blot experiment of UNC5c protein levels in the nucleus accumbens of male mice at postnatal days 15, 21 or 35 and reveals a significant increase in protein levels at the onset adolescence.

Our methods for this Western blot were as follows: Samples were prepared as previously (Torres-Berrío et al., 2017). Briefly, mice were sacrificed by live decapitation and brains were flash frozen in heptane on dry ice for 10 seconds. Frozen brains were mounted in a cryomicrotome and two 500um sections were collected for the nucleus accumbens, corresponding to plates 14 and 18 of the Paxinos mouse brain atlas. Two tissue core samples were collected per section, one for each side of the brain, using a 15-gauge tissue corer (Fine surgical tools Cat no. NC9128328) and ejected in a microtube on dry ice. The tissue samples were homogenized in 100ul of standard radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer using a handheld electric tissue homogenizer. The samples were clarified by centrifugation at 4C at a speed of 15000g for 30 minutes. Protein concentration was quantified using a bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Pierce BCA protein assay kit, Cat no.PI23225) and denatured with standard Laemmli buffer for 5 minutes at 70C. 10ug of protein per sample was loaded and run by SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis in a Mini-PROTEAN system (Bio-Rad) on an 8% acrylamide gel by stacking for 30 minutes at 60V and resolving for 1.5 hours at 130V. The proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for 1 hour at 100V in standard transfer buffer on ice. The membranes were blocked using 5% bovine serum albumin dissolved in tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 and probed with primary (UNC5c, Abcam Cat. no ab302924) and HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hour. a-tubulin was probed and used as loading control. The probed membranes were resolved using SuperSignal West Pico PLUS chemiluminescent substrate (ThermoFisher Cat no.34579) in a ChemiDoc MP Imaging system (Bio-Rad). Band intensity was quantified using the ChemiDoc software and all ages were normalized to the P15 age group average.

Validation of the UNC5c antibody was performed in the lab of Dr. Liu, from whom it was kindly provided. Briefly, in the validation study the authors showed that the anti-UNC5C antibody can detect endogenous UNC5C expression and the level of UNC5C is dramatically reduced after UNC5C knockdown. The antibody can also detect the tagged-UNC5C protein in several cell lines, which was confirmed by a tag antibody (Purohit et al., 2012; Shao et al., 2017).

References:

Purohit AA, Li W, Qu C, Dwyer T, Shao Q, Guan K-L, Liu G. 2012. Down Syndrome Cell Adhesion Molecule (DSCAM) Associates with Uncoordinated-5C (UNC5C) in Netrin-1mediated Growth Cone Collapse. The Journal of biological chemistry 287:27126–27138. doi:10.1074/jbc.m112.340174

Shao Q, Yang T, Huang H, Alarmanazi F, Liu G. 2017. Uncoupling of UNC5C with Polymerized TUBB3 in Microtubules Mediates Netrin-1 Repulsion. J Neurosci 37:5620–5633. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.2617-16.2017

(10) "In adolescence, dopamine neurons begin to express the repulsive Netrin-1 receptor UNC5C, and reduction in UNC5C expression appears to cause growth of mesolimbic dopamine axons to the prefrontal cortex".....This is confusing. Figure 2 shows a developmental increase in UNc5c not a decrease. So when is the "reduction in Unc5c expression" occurring?

We apologize for the mistake in this sentence. We have corrected the relevant passage in our manuscript as follows:

In adolescence, dopamine neurons begin to express the repulsive Netrin-1 receptor UNC5C, particularly when mesolimbic and mesocortical dopamine projections segregate in the nucleus accumbens (Manitt et al., 2010; Reynolds et al., 2018a). In contrast, dopamine axons in the prefrontal cortex do not express UNC5c except in very rare cases (Supplementary Figure 4). In adult male mice with Unc5c haploinsufficiency, there appears to be ectopic growth of mesolimbic dopamine axons to the prefrontal cortex (Auger et al., 2013). This miswiring is associated with alterations in prefrontal cortex-dependent behaviours (Auger et al., 2013).

References:

Auger ML, Schmidt ERE, Manitt C, Dal-Bo G, Pasterkamp RJ, Flores C. 2013. unc5c haploinsufficient phenotype: striking similarities with the dcc haploinsufficiency model. European Journal of Neuroscience 38:2853–2863. doi:10.1111/ejn.12270

Manitt C, Labelle-Dumais C, Eng C, Grant A, Mimee A, Stroh T, Flores C. 2010. Peri-Pubertal Emergence of UNC-5 Homologue Expression by Dopamine Neurons in Rodents. PLoS ONE 5:e11463-14. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011463

Reynolds LM, Pokinko M, Torres-Berrío A, Cuesta S, Lambert LC, Pellitero EDC, Wodzinski M, Manitt C, Krimpenfort P, Kolb B, Flores C. 2018a. DCC Receptors Drive Prefrontal Cortex Maturation by Determining Dopamine Axon Targeting in Adolescence. Biological psychiatry 83:181–192. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.06.009

(11) In Fig 3, a statistical comparison should be made between summer male and winter male, to justify the conclusions that the winter males have delayed DA innervation.

This analysis was also suggested by Reviewer 1, #11. Here is our response:

We analyzed the summer and winter data together in ANOVAs separately for males and females. In both sexes we find a significant effect of daylength on dopamine innervation, interacting with age. Male age by daylength interaction: F = 6.383, p = 0.00242. Female age by daylength interaction: F = 21.872, p = 1.97 x 10-9. The full statistical analysis is available as a supplement to this letter (Response_Letter_Stats_Details.docx).

(12) Should axon length also be measured here (Fig 3)? It is not clear why the authors have switched to varicosity density. Also, a box should be drawn in the NAC cartoon to indicate the region that was sampled.

It is untenable to quantify axon length in the prefrontal cortex as we cannot distinguish independent axons. Rather, they are “tangled”; they twist and turn in a multitude of directions as they make contact with various dendrites. Furthermore, they branch extensively. It would therefore be impossible to accurately quantify the number of axons. Using unbiased stereology to quantify varicosities is a valid, well-characterized and straightforward alternative (Reynolds et al., 2022).

References:

Reynolds LM, Pantoja-Urbán AH, MacGowan D, Manitt C, Nouel D, Flores C. 2022. Dopaminergic System Function and Dysfunction: Experimental Approaches. Neuromethods 31–63. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-2799-0_2

(13) In Fig 3, Unc5c should be quantified to bolster the interesting finding that Unc5c expression dynamics are different between summer and winter hamsters. Unc5c mRNA experiments would also be important to see if similar changes are observed at the transcript level.

We agree that it would be very interesting to see how UNC5c mRNA and protein levels change over time in summer and winter hamsters, both in males, as the reviewer suggests here, and in females. We are working on conducting these experiments in hamsters as part of a broader expansion of our research in this area. These experiments will require a lengthy amount of time and at this point we feel that they are beyond the scope of this manuscript.

(14) Fig 4. The peak in exploratory behavior in winter females is counterintuitive and needs to be better discussed. IN general, the light dark behavior seems quite variable.

This is indeed a very interesting finding, which we have expanded upon in our manuscript as follows:

When raised under a winter-mimicking daylength, hamsters of either sex show a protracted peak in risk taking. In males, it is delayed beyond 80 days old, but the delay is substantially less in females. This is a counterintuitive finding considering that dopamine development in winter females appears to be accelerated. Our interpretation of this finding is that the timing of the risk-taking peak in females may reflect a balance between different adolescent developmental processes. The fact that dopamine axon growth is accelerated does not imply that all adolescent maturational processes are accelerated. Some may be delayed, for example those that induce axon pruning in the cortex. The timing of the risk-taking peak in winter female hamsters may therefore reflect the amalgamation of developmental processes that are advanced with those that are delayed – producing a behavioural effect that is timed somewhere in the middle. Disentangling the effects of different developmental processes on behaviour will require further experiments in hamsters, including the direct manipulation of dopamine activity in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex.

Full Reference List

Auger ML, Schmidt ERE, Manitt C, Dal-Bo G, Pasterkamp RJ, Flores C. 2013. unc5c haploinsufficient phenotype: striking similarities with the dcc haploinsufficiency model. European Journal of Neuroscience 38:2853–2863. doi:10.1111/ejn.12270

Bari A, Robbins TW. 2013. Inhibition and impulsivity: Behavioral and neural basis of response control. Progress in neurobiology 108:44–79. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.06.005

Cuesta S, Nouel D, Reynolds LM, Morgunova A, Torres-Berrío A, White A, Hernandez G, Cooper HM, Flores C. 2020. Dopamine Axon Targeting in the Nucleus Accumbens in Adolescence Requires Netrin-1. Frontiers Cell Dev Biology 8:487. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.00487

Daubaras M, Bo GD, Flores C. 2014. Target-dependent expression of the netrin-1 receptor, UNC5C, in projection neurons of the ventral tegmental area. Neuroscience 260:36–46. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.12.007

Eagle DM, Bari A, Robbins TW. 2008. The neuropsychopharmacology of action inhibition: crossspecies translation of the stop-signal and go/no-go tasks. Psychopharmacology 199:439– 456. doi:10.1007/s00213-008-1127-6

Hoops D, Flores C. 2017. Making Dopamine Connections in Adolescence. Trends in Neurosciences 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2017.09.004

Jonker FA, Jonker C, Scheltens P, Scherder EJA. 2015. The role of the orbitofrontal cortex in cognition and behavior. Rev Neurosci 26:1–11. doi:10.1515/revneuro-2014-0043

Kim B, Im H. 2019. The role of the dorsal striatum in choice impulsivity. Ann N York Acad Sci 1451:92–111. doi:10.1111/nyas.13961

Kim D, Ackerman SL. 2011. The UNC5C Netrin Receptor Regulates Dorsal Guidance of Mouse Hindbrain Axons. J Neurosci 31:2167–2179. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.5254-10.2011

Manitt C, Labelle-Dumais C, Eng C, Grant A, Mimee A, Stroh T, Flores C. 2010. Peri-Pubertal Emergence of UNC-5 Homologue Expression by Dopamine Neurons in Rodents. PLoS ONE 5:e11463-14. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011463

Murcia-Belmonte V, Coca Y, Vegar C, Negueruela S, Romero C de J, Valiño AJ, Sala S, DaSilva R, Kania A, Borrell V, Martinez LM, Erskine L, Herrera E. 2019. A Retino-retinal Projection Guided by Unc5c Emerged in Species with Retinal Waves. Current Biology 29:1149-1160.e4. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.02.052

Ott T, Stein AM, Nieder A. 2023. Dopamine receptor activation regulates reward expectancy signals during cognitive control in primate prefrontal neurons. Nat Commun 14:7537. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-43271-6

Phillips RA, Tuscher JJ, Black SL, Andraka E, Fitzgerald ND, Ianov L, Day JJ. 2022. An atlas of transcriptionally defined cell populations in the rat ventral tegmental area. Cell Reports 39:110616. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110616

Purohit AA, Li W, Qu C, Dwyer T, Shao Q, Guan K-L, Liu G. 2012. Down Syndrome Cell Adhesion Molecule (DSCAM) Associates with Uncoordinated-5C (UNC5C) in Netrin-1-mediated Growth Cone Collapse. The Journal of biological chemistry 287:27126–27138. doi:10.1074/jbc.m112.340174

Reynolds LM, Hernandez G, MacGowan D, Popescu C, Nouel D, Cuesta S, Burke S, Savell KE, Zhao J, Restrepo-Lozano JM, Giroux M, Israel S, Orsini T, He S, Wodzinski M, Avramescu RG, Pokinko M, Epelbaum JG, Niu Z, Pantoja-Urbán AH, Trudeau L-É, Kolb B, Day JJ, Flores C. 2023. Amphetamine disrupts dopamine axon growth in adolescence by a sex-specific mechanism in mice. Nat Commun 14:4035. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-39665-1

Reynolds LM, Pantoja-Urbán AH, MacGowan D, Manitt C, Nouel D, Flores C. 2022. Dopaminergic System Function and Dysfunction: Experimental Approaches. Neuromethods 31–63. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-2799-0_2

Reynolds LM, Pokinko M, Torres-Berrío A, Cuesta S, Lambert LC, Pellitero EDC, Wodzinski M, Manitt C, Krimpenfort P, Kolb B, Flores C. 2018a. DCC Receptors Drive Prefrontal Cortex Maturation by Determining Dopamine Axon Targeting in Adolescence. Biological psychiatry 83:181–192. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.06.009

Reynolds LM, Yetnikoff L, Pokinko M, Wodzinski M, Epelbaum JG, Lambert LC, Cossette M-P, Arvanitogiannis A, Flores C. 2018b. Early Adolescence is a Critical Period for the Maturation of Inhibitory Behavior. Cerebral cortex 29:3676–3686. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhy247

Schlienger S, Yam PT, Balekoglu N, Ducuing H, Michaud J-F, Makihara S, Kramer DK, Chen B, Fasano A, Berardelli A, Hamdan FF, Rouleau GA, Srour M, Charron F. 2023. Genetics of mirror movements identifies a multifunctional complex required for Netrin-1 guidance and lateralization of motor control. Sci Adv 9:eadd5501. doi:10.1126/sciadv.add5501

Shao Q, Yang T, Huang H, Alarmanazi F, Liu G. 2017. Uncoupling of UNC5C with Polymerized TUBB3 in Microtubules Mediates Netrin-1 Repulsion. J Neurosci 37:5620–5633. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.2617-16.2017

Srivatsa S, Parthasarathy S, Britanova O, Bormuth I, Donahoo A-L, Ackerman SL, Richards LJ, Tarabykin V. 2014. Unc5C and DCC act downstream of Ctip2 and Satb2 and contribute to corpus callosum formation. Nat Commun 5:3708. doi:10.1038/ncomms4708

Torres-Berrío A, Lopez JP, Bagot RC, Nouel D, Dal-Bo G, Cuesta S, Zhu L, Manitt C, Eng C, Cooper HM, Storch K-F, Turecki G, Nestler EJ, Flores C. 2017. DCC Confers Susceptibility to Depression-like Behaviors in Humans and Mice and Is Regulated by miR-218. Biological psychiatry 81:306–315. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.08.017

Vassilev P, Pantoja-Urban AH, Giroux M, Nouel D, Hernandez G, Orsini T, Flores C. 2021. Unique effects of social defeat stress in adolescent male mice on the Netrin-1/DCC pathway, prefrontal cortex dopamine and cognition (Social stress in adolescent vs. adult male mice). Eneuro ENEURO.0045-21.2021. doi:10.1523/eneuro.0045-21.2021

Private Comments

Reviewer #1

(12) The language should be improved. Some expression is confusing (line178-179). Also some spelling errors (eg. Figure 1M).

We have removed the word “Already” to make the sentence in lines 178-179 clearer, however we cannot find a spelling error in Figure 1M or its caption. We have further edited the manuscript for clarity and flow.

Reviewer #2

(1) The authors claim to have revealed how the 'timing of adolescence is programmed in the brain'. While their findings certainly shed light on molecular, circuit and behavioral processes that are unique to adolescence, their claim may be an overstatement. I suggest they refine this statement to discuss more specifically the processes they observed in the brain and animal behavior, rather than adolescence itself.

We agree with the reviewer and have revised the manuscript to specify that we are referring to the timing of specific developmental processes that occur in the adolescent brain, not adolescence overall.

(2) Along the same lines, the authors should also include a more substantiative discussion of how they selected their ages for investigation (for both mice and hamsters), For mice, their definition of adolescence (P21) is earlier than some (e.g. Spear L.P., Neurosci. and Beh. Reviews, 2000).

There are certainly differences of opinion between researchers as to the precise definition of adolescence and the period it encompasses. Spear, 2000, provides one excellent discussion of the challenges related to identifying adolescence across species. This work gives specific ages only for rats, not mice (as we use here), and characterizes post-natal days 28-42 as being the conservative age range of “peak” adolescence (page 419, paragraph 1). Immediately thereafter the review states that the full adolescent period is longer than this, and it could encompass post-natal days 20-55 (page 419, paragraph 2).

We have added the following statement to our methods:

There is no universally accepted way to define the precise onset of adolescence. Therefore, there is no clear-cut boundary to define adolescent onset in rodents (Spear, 2000). Puberty can be more sharply defined, and puberty and adolescence overlap in time, but the terms are not interchangeable. Puberty is the onset of sexual maturation, while adolescence is a more diffuse period marked by the gradual transition from a juvenile state to independence. We, and others, suggest that adolescence in rodents spans from weaning (postnatal day 21) until adulthood, which we take to start on postnatal day 60 (Reynolds and Flores, 2021). We refer to “early adolescence” as the first two weeks postweaning (postnatal days 21-34). These ranges encompass discrete DA developmental periods (Kalsbeek et al., 1988; Manitt et al., 2011; Reynolds et al., 2018a), vulnerability to drug effects on DA circuitry (Hammerslag and Gulley, 2014; Reynolds et al., 2018a), and distinct behavioral characteristics (Adriani and Laviola, 2004; Makinodan et al., 2012; Schneider, 2013; Wheeler et al., 2013).

References:

Adriani W, Laviola G. 2004. Windows of vulnerability to psychopathology and therapeutic strategy in the adolescent rodent model. Behav Pharmacol 15:341–352. doi:10.1097/00008877-200409000-00005

Hammerslag LR, Gulley JM. 2014. Age and sex differences in reward behavior in adolescent and adult rats. Dev Psychobiol 56:611–621. doi:10.1002/dev.21127

Hoops D, Flores C. 2017. Making Dopamine Connections in Adolescence. Trends in Neurosciences 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2017.09.004

Kalsbeek A, Voorn P, Buijs RM, Pool CW, Uylings HBM. 1988. Development of the Dopaminergic Innervation in the Prefrontal Cortex of the Rat. The Journal of Comparative Neurology 269:58–72. doi:10.1002/cne.902690105

Makinodan M, Rosen KM, Ito S, Corfas G. 2012. A critical period for social experiencedependent oligodendrocyte maturation and myelination. Science 337:1357–1360. doi:10.1126/science.1220845

Manitt C, Mimee A, Eng C, Pokinko M, Stroh T, Cooper HM, Kolb B, Flores C. 2011. The Netrin Receptor DCC Is Required in the Pubertal Organization of Mesocortical Dopamine Circuitry. J Neurosci 31:8381–8394. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.0606-11.2011

Reynolds LM, Flores C. 2021. Mesocorticolimbic Dopamine Pathways Across Adolescence: Diversity in Development. Front Neural Circuit 15:735625. doi:10.3389/fncir.2021.735625

Reynolds LM, Yetnikoff L, Pokinko M, Wodzinski M, Epelbaum JG, Lambert LC, Cossette MP, Arvanitogiannis A, Flores C. 2018. Early Adolescence is a Critical Period for the Maturation of Inhibitory Behavior. Cerebral cortex 29:3676–3686. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhy247

Schneider M. 2013. Adolescence as a vulnerable period to alter rodent behavior. Cell and tissue research 354:99–106. Doi:10.1007/s00441-013-1581-2

Spear LP. 2000. Neurobehavioral Changes in Adolescence. Current directions in psychological science 9:111–114. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00072

Wheeler AL, Lerch JP, Chakravarty MM, Friedel M, Sled JG, Fletcher PJ, Josselyn SA, Frankland PW. 2013. Adolescent Cocaine Exposure Causes Enduring Macroscale Changes in Mouse Brain Structure. J Neurosci 33:1797–1803. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.3830-12.2013

(3) Figure 1 - the conclusions hinge on the Netrin-1 staining, as shown in panel G, but the cells are difficult to see. It would be helpful to provide clearer, more zoomed images so readers can better assess the staining. Since Netrin-1 expression reduces dramatically after P4 and they had to use antigen retrieval to see signal, it would be helpful to show some images from additional brain regions and ages to see if expression levels follow predicted patterns. For instance, based on the allen brain atlas, it seems that around P21, there should be high levels of Netrin-1 in the cerebellum, but low levels in the cortex. These would be nice controls to demonstrate the specificity and sensitivity of the antibody in older tissue.

We do not study the cerebellum and have never stained this region; doing so now would require generating additional tissue and we’re not sure it would add enough to the information provided to be worthwhile. Note that we have stained the forebrain for Netrin-1 previously, providing broad staining of many brain regions (Manitt et al., 2011)

References:

Manitt C, Mimee A, Eng C, Pokinko M, Stroh T, Cooper HM, Kolb B, Flores C. 2011. The Netrin Receptor DCC Is Required in the Pubertal Organization of Mesocortical Dopamine Circuitry. J Neurosci 31:8381–8394. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.0606-11.2011

(4) Figure 3 - Because mice tend to avoid brightly-lit spaces, the light/dark box is more commonly used as a measure of anxiety-like behavior than purely exploratory behavior (including in the paper they cited). It is important to address this possibility in their discussion of their findings. To bolster their conclusions about the coincidence of circuit and behavioral changes in adolescent hamsters, it would be useful to add an additional measure of exploratory behaviors (e.g. hole board).

Regarding the light/dark box test, this is an excellent point. We prefer the term “risk taking” to “anxiety-like” and now use the former term in our manuscript. Furthermore, our interest in the behaviour is purely to chart the development of adolescent behaviour across our treatment groups, not to study a particular emotional state. Regardless of the specific emotion or emotions governing the light/dark box behaviour, it is an ideal test for charting adolescent shifts in behaviour as it is well-characterized in this respect, as we discuss in our manuscript.

(5) Supplementary Figure 4,5 The authors defined puberty onset using uterine and testes weights in hamsters. While the weights appear to be different for summer and winter hamsters, there were no statistical comparison. Please add statistical analyses to bolster claims about puberty start times. Also, as many studies use vaginal opening to define puberty onset, it would be helpful to discuss how these measurements typically align and cite relevant literature that described use of uterine weights. Also, Supplementary Figures 4 and 5 were mis-cited as Supp. Fig. 2 in the text (e.g. line 317 and others).

These are great suggestions. We have added statistical analyses to Supplementary Figures 5 and 6 and provided Vaginal Opening data as Supplementary Figure 7. The statistical analyses confirm that all three characters are delayed in winter hamsters compared to summer hamsters.

We have also added the following references to the manuscript:

Darrow JM, Davis FC, Elliott JA, Stetson MH, Turek FW, Menaker M. 1980. Influence of Photoperiod on Reproductive Development in the Golden Hamster. Biol Reprod 22:443–450. doi:10.1095/biolreprod22.3.443

Ebling FJP. 1994. Photoperiodic Differences during Development in the Dwarf Hamsters Phodopus sungorus and Phodopus campbelli. Gen Comp Endocrinol 95:475–482. doi:10.1006/gcen.1994.1147

Timonin ME, Place NJ, Wanderi E, Wynne-Edwards KE. 2006. Phodopus campbelli detect reduced photoperiod during development but, unlike Phodopus sungorus, retain functional reproductive physiology. Reproduction 132:661–670. doi:10.1530/rep.1.00019

(6) The font in many figure panels is small and hard to read (e.g. 1A,D,E,H,I,L...). Please increase the size for legibility.

We have increased the font size of our figure text throughout the manuscript.

Reviewer #3

(15) Fig 1 C,D. Clarify the units of the y axis

We have now fixed this.

Full Reference List

Adriani W, Laviola G. 2004. Windows of vulnerability to psychopathology and therapeutic strategy in the adolescent rodent model. Behav Pharmacol 15:341–352. doi:10.1097/00008877-200409000-00005

Hammerslag LR, Gulley JM. 2014. Age and sex differences in reward behavior in adolescent and adult rats. Dev Psychobiol 56:611–621. doi:10.1002/dev.21127

Hoops D, Flores C. 2017. Making Dopamine Connections in Adolescence. Trends in Neurosciences 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2017.09.004

Kalsbeek A, Voorn P, Buijs RM, Pool CW, Uylings HBM. 1988. Development of the Dopaminergic Innervation in the Prefrontal Cortex of the Rat. The Journal of Comparative Neurology 269:58–72. doi:10.1002/cne.902690105

Makinodan M, Rosen KM, Ito S, Corfas G. 2012. A critical period for social experiencedependent oligodendrocyte maturation and myelination. Science 337:1357–1360. doi:10.1126/science.1220845

Manitt C, Mimee A, Eng C, Pokinko M, Stroh T, Cooper HM, Kolb B, Flores C. 2011. The Netrin Receptor DCC Is Required in the Pubertal Organization of Mesocortical Dopamine Circuitry. J Neurosci 31:8381–8394. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.0606-11.2011

Reynolds LM, Flores C. 2021. Mesocorticolimbic Dopamine Pathways Across Adolescence: Diversity in Development. Front Neural Circuit 15:735625. doi:10.3389/fncir.2021.735625 Reynolds LM, Yetnikoff L, Pokinko M, Wodzinski M, Epelbaum JG, Lambert LC, Cossette M-P, Arvanitogiannis A, Flores C. 2018. Early Adolescence is a Critical Period for the Maturation of Inhibitory Behavior. Cerebral cortex 29:3676–3686. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhy247

Schneider M. 2013. Adolescence as a vulnerable period to alter rodent behavior. Cell and tissue research 354:99–106. doi:10.1007/s00441-013-1581-2

Spear LP. 2000. Neurobehavioral Changes in Adolescence. Current directions in psychological science 9:111–114. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00072

Wheeler AL, Lerch JP, Chakravarty MM, Friedel M, Sled JG, Fletcher PJ, Josselyn SA, Frankland PW. 2013. Adolescent Cocaine Exposure Causes Enduring Macroscale Changes in Mouse Brain Structure. J Neurosci 33:1797–1803. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.3830-12.2013