Author Response

eLife assessment

The authors' finding that PARG hydrolase removal of polyADP-ribose (PAR) protein adducts generated in response to the presence of unligated Okazaki fragments is important for S-phase progression is potentially valuable, but the evidence is incomplete, and identification of relevant PARylated PARG substrates in S-phase is needed to understand the role of PARylation and dePARylation in S-phase progression. Their observation that human ovarian cancer cells with low levels of PARG are more sensitive to a PARG inhibitor, presumably due to the accumulation of high levels of protein PARylation, suggests that low PARG protein levels could serve as a criterion to select ovarian cancer patients for treatment with a PARG inhibitor drug.

Thank you for the assessment and summary. Please see below for details as we have now addressed the deficiencies pointed out by the reviewers.

We believe that PARP1 is one of the major relevant PARG substrates in S phase cells. Previous studies reported that PARP1 recognizes unligated Okazaki fragments and induces S phase PARylation, which recruits single-strand break repair proteins such as XRCC1 and LIG3 that acts as a backup pathway for Okazaki fragment maturation (Hanzlikova et al., 2018; Kumamoto et al., 2021). In this study, we revealed that accumulation of PARP1/2-dependent S phase PARylation eventually led to cell death (Fig. 2). Furthermore, we found that chromatin-bound PARP1 as well as PARylated PARP1 increased in PARG KO cells (Fig. S4A and Fig. 4A), suggesting that PARP1 is one of the key substrates of PARG in S phase cells. Of course, PARG may have additional substrates besides PARP1 which are required for its roles in S phase progression, as PARG is known to be recruited to DNA damage sites through pADPr- and PCNA-dependent mechanisms (Mortusewicz et al., 2011). Precisely how PARG regulates S phase progression warrants further investigation.

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

I have a major conceptual problem with this manuscript: How can the full deletion of a gene (PARG) sensitize a cell to further inhibition by its chemical inhibitor (PARGi) since the target protein is fully absent?

Please see below for details about this point. Briefly, we found that PARG is an essential gene (Fig. 7). There was residual PARG activity in our PARG KO cells, although the loss of full-length PARG was confirmed by Western blotting and DNA sequencing (Fig. S9). The residual PARG activity in these cells can be further inhibited by PARG inhibitor, which eventually lead to cell death.

The authors state in the discussion section: "The residual PARG dePARylation activity observed in PARG KO cells likely supports cell growth, which can be further inhibited by PARGi". What does this statement mean? Is the authors' conclusion that their PARG KOs are not true KOs but partial hypomorphic knockdowns? Were the authors working with KO clones or CRISPR deletion in populations of cells?

The reviewer is correct that our PARG KOs are not true KOs. We were working with CRISPR edited KO clones. As shown in this manuscript, we validated our KO clones by Western blotting, DNA sequencing and MMS-induced PARylation. Despite these efforts and our inability to detect full-length PARG in our KO clones, we suspect that our PARG KO cells may still express one or more active fragments of PARG due to alternative splicing and/or alternative ATG usage.

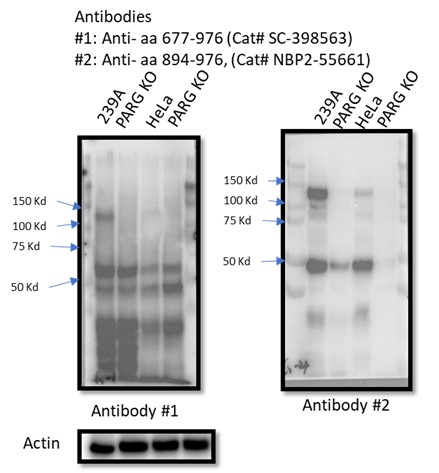

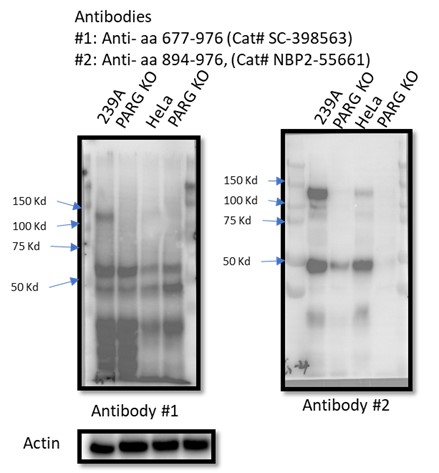

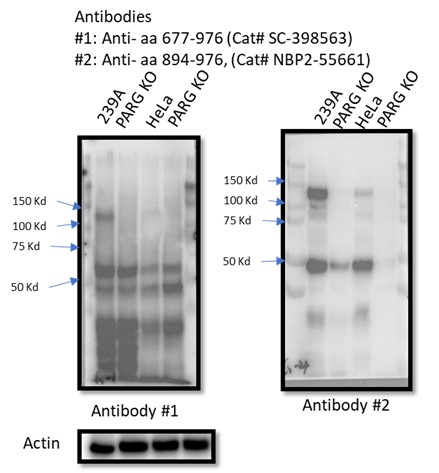

As shown in Fig. 7, we believe that PARG is essential for proliferation. Our initial KO cell lines are not complete PARG KO cells and residual PARG activity in these cells could support cell proliferation. Unfortunately, due to lack of appropriate reagents we could not draw solid conclusions regarding the isoforms or the truncated PARG expressed in these cells (Please see Western blots below).

Are there splice variants of PARG that were not knocked down? Are there PARP paralogues that can complement the biochemical activity of PARG in the PARG KOs? The authors do not discuss these critical issues nor engage with this problem.

There are five reviewed or potential PARG isoforms identified in the Uniprot database. The sgRNAs used to generate initial PARG KO cells in this manuscript target all three catalytically active isoforms (isoforms 1, 2 and 3), while isoforms 4 and 5 are considered catalytically inactive according to the Uniprot database. However, it is likely that sgRNA-mediated genome editing may lead to the creation of new alternatively spliced PARG mRNAs or the use of alternative ATG, which can produce catalytically active forms of PARG. Instead of searching for these putative spliced PARG RNAs, we used two independent antibodies that recognize the C-terminus of PARG for WB as shown in Author response image 1. Unfortunately, besides full-length PARG, these antibodies also recognized several other bands, some of them were reduced or absent in PARG KO cells, others were not. Thus, we could not draw a clear conclusion which functional isoform was expressed in our PARG KO cells. Nevertheless, we directly measured PARG activity in PARG KO cells (Fig. S9) and showed that we were still able to detect residual PARG activity in these PARG KO cells. These data clearly indicate that residual PARG activity are present and detected in our KO cells, but the precise nature of these truncated forms of PARG remains elusive.

Author response image 1.

These issues have to be dealt with upfront in the manuscript for the reader to make sense of their work.

We thank this reviewer for his/her constructive comments and suggestions. We will include the data above and additional discussion upfront in our revised manuscript to avoid any further confusion by our readers.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary:

In this manuscript, Nie et al investigate the effect of PARG KO and PARG inhibition (PARGi) on pADPR, DNA damage, cell viability, and synthetic lethal interactions in HEK293A and Hela cells. Surprisingly, the authors report that PARG KO cells are sensitive to PARGi and show higher pADPR levels than PARG KO cells, which are abrogated upon deletion or inhibition of PARP1/PARP2. The authors explain the sensitivity of PARG KO to PARGi through incomplete PARG depletion and demonstrate complete loss of PARG activity when incomplete PARG KO cells are transfected with additional gRNAs in the presence of PARPi. Furthermore, the authors show that the sensitivity of PARG KO cells to PARGi is not caused by NAD depletion but by S-phase accumulation of pADPR on chromatin coming from unligated Okazaki fragments, which are recognized and bound by PARP1. Consistently, PARG KO or PARG inhibition shows synthetic lethality with Pol beta, which is required for Okazaki fragment maturation. PARG expression levels in ovarian cancer cell lines correlate negatively with their sensitivity to PARGi.

Thank you for your nice comments. The complete loss of PARG activity was observed in PARG complete/conditional KO (cKO) cells. These cKO clones were generated using wild-type cells transfected with sgRNAs targeting the catalytic domain of PARG in the presence of PARP inhibitor.

Strengths:

The authors show that PARG is essential for removing ADP-ribosylation in S-phase.

Thanks!

Weaknesses:

- This begs the question as to the relevant substrates of PARG in S-phase, which could be addressed, for example, by analysing PARylated proteins associated with replication forks in PARG-depleted cells (EdU pulldown and Af1521 enrichment followed by mass spectrometry).

We believe that PARP1 is one of the major relevant PARG substrates in S phase cells. Previous studies reported that PARP1 recognizes unligated Okazaki fragments and induces S phase PARylation, which recruits single-strand break repair proteins such as XRCC1 and LIG3 that acts as a backup pathway for Okazaki fragment maturation (Hanzlikova et al., 2018; Kumamoto et al., 2021). In this study, we revealed that accumulation of PARP1/2-dependent S phase PARylation eventually led to cell death (Fig. 2). Furthermore, we found that chromatin-bound PARP1 as well as PARylated PARP1 increased in PARG KO cells (Fig. S4A and Fig. 4A), suggesting that PARP1 is one of the key substrates of PARG in S phase cells. Of course, PARG may have additional substrates besides PARP1 which are required for its roles in S phase progression, as PARG is known to be recruited to DNA damage sites through pADPr- and PCNA-dependent mechanisms (Mortusewicz et al., 2011). Precisely how PARG regulates S phase progression warrants further investigation.

- The results showing the generation of a full PARG KO should be moved to the beginning of the Results section, right after the first Results chapter (PARG depletion leads to drastic sensitivity to PARGi), otherwise, the reader is left to wonder how PARG KO cells can be sensitive to PARGi when there should be presumably no PARG present.

Thank you for your suggestion! However, we would like to keep the complete PARG KO result at the end of the Results section, since this was how this project evolved. Initially, we did not know that PARG is an essential gene. Thus, we speculated that PARGi may target not only PARG but also a second target, which only becomes essential in the absence of PARG. To test this possibility, we performed FACS-based and cell survival-based whole-genome CRISPR screens (Fig. 5). However, this putative second target was not revealed by our CRISPR screening data (Fig. 5). We then tested the possibility that these cells may have residual PARG expression or activity and only cells with very low PARG expression are sensitive to PARGi, which turned out to be the case for ovarian cancer cells. Equipped with PARP inhibitor and sgRNAs targeting the catalytic domain of PARG, we finally generated cells with complete loss of PARG activity to prove that PARG is an essential gene (Fig. 7). This series of experiments underscore the challenge of validating any KO cell lines, i.e. the identification of frame-shift mutations, absence of full-length proteins, and phenotypic changes may still not be sufficient to validate KO clones. This is an important lesson we learned and we would like to share it with the scientific community.

To avoid further misunderstanding, we will include additional statements/comments at the end of “PARG depletion leads to drastic sensitivity to PARGi” section and at the beginning of “CRISPR screens reveal genes responsible for regulating pADPr signaling and/or cell lethality in WT and PARG KO cells”. Hope that our revised manuscript will make it clear.

- Please indicate in the first figure which isoforms were targeted with gRNAs, given that there are 5 PARG isoforms. You should also highlight that the PARG antibody only recognizes the largest isoform, which is clearly absent in your PARG KO, but other isoforms may still be produced, depending on where the cleavage sites were located.

The sgRNAs used to generate PARG KO cells in this manuscript target all three catalytically active isoforms (isoforms 1, 2 and 3), while isoforms 4 and 5 are considered catalytically inactive according to the Uniprot database. As suggested, we will modify Fig. S1D and the figure legends.

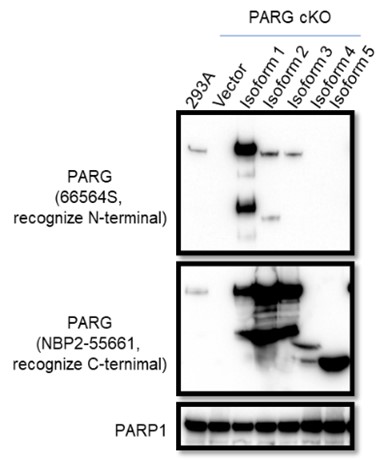

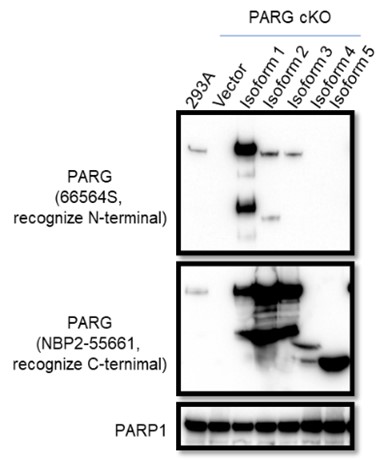

The manufacturer instruction states that the Anti-PARG antibody (66564S) can only recognize isoform 1, this antibody could recognize isoforms 2 and 3 albeit weakly based on Western blot results with lysates prepared from PARG cKO cells reconstituted with different PARG isoforms, as shown below. As suggested, we will add a statement in the revised manuscript and provide the Western blotting data in Author response image 2.

Author response image 2.

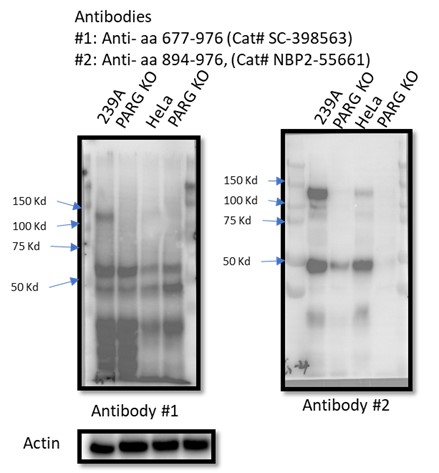

To test whether other isoforms were expressed in 293A and/or HeLa cells, we used two independent antibodies that recognize the C-terminus of PARG for WB as shown in Author response image 3. Unfortunately, besides full-length PARG, these antibodies also recognized several other bands, some of them were reduced or absent in PARG KO cells, others were not. Thus, we could not draw a clear conclusion which functional isoforms or truncated forms were expressed in our PARG KO cells.

Author response image 3.

- FACS data need to be quantified. Scatter plots can be moved to Supplementary while quantification histograms with statistical analysis should be placed in the main figures.

We agree with this reviewer that quantification of FACS data may provide straightforward results in some of our data. However, it is challenging to quantify positive S phase pADPr signaling in some panels, for example in Fig. 3A and Fig. 4C. In both panels, pADPr signaling was detected throughout the cell cycle and therefore it is difficult to know the percentage of S phase pADPr signaling in these samples. Thus, we decide to keep the scatter plots to demonstrate the dramatic and S phase-specific pADPr signaling in PARG KO cells treated with PARGi. We hope that these data are clear and convincing even without any quantification.

- All colony formation assays should be quantified and sensitivity plots should be shown next to example plates.

As suggested, we will include the sensitivity plot next to Fig. 3D. However, other colony formation assays in this study were performed with a single concentration of inhibitor and therefore we will not provide sensitivity plots for these experiments. Nevertheless, the results of these experiments are straightforward and easy to interpret.

- Please indicate how many times each experiment was performed independently and include statistical analysis.

As suggested, we will add this information in the revised manuscript.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Here the authors carried out a CRISPR/sgRNA screen with a DDR gene-targeted mini-library in HEK293A cells looking for genes whose loss increased sensitivity to treatment with the PARG inhibitor, PDD00017273 (PARGi). Surprisingly they found that PARG itself, which encodes the cellular poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (dePARylation) enzyme, was a major hit. Targeted PARG KO in 293A and HeLa cells also caused high sensitivity to PARGi. When PARG KO cells were reconstituted with catalytically-dead PARG, MMS treatment caused an increase in PARylation, not observed when cells were reconstituted with WT PARG or when the PARG KO was combined with PARP1/2 DKO, suggesting that loss of PARG leads to a strong PARP1/2-dependent increase in protein PARylation. The decrease in intracellular NADH+, the substrate for PARP-driven PARylation, observed in PARG KO cells was reversed by treatment with NMN or NAM, and this treatment partially rescued the PARG KO cell lethality. However, since NAD+ depletion with the FK868 nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) inhibitor did not induce a similar lethality the authors concluded that NAD+ depletion/reduction was only partially responsible for the PARGi toxicity. Interestingly, PARylation was also observed in untreated PARG KO cells, specifically in S phase, without a significant rise in γH2AX signals. Using cells synchronized at G1/S by double thymidine blockade and release, they showed that entry into S phase was necessary for PARGi to induce PARylation in PARG KO cells. They found an increased association of PARP1 with a chromatin fraction in PARG KO cells independent of PARGi treatment, and suggested that PARP1 trapping on chromatin might account in part for the increased PARGi sensitivity. They also showed that prolonged PARGi treatment of PARG KO cells caused S phase accumulation of pADPr eventually leading to DNA damage, as evidenced by increased anti-γH2AX antibody signals and alkaline comet assays. Based on the use of emetine, they deduced that this response could be caused by unligated Okazaki fragments. Next, they carried out FACS-based CRISPR screens to identify genes that might be involved in cell lethality in WT and PARG KO cells, finding that loss of base excision repair (BER) and DNA repair genes led to increased PARylation and PARGi sensitivity, whereas loss of PARP1 had the opposite effects. They also found that BER pathway disruption exhibited synthetic lethality with PARGi treatment in both PARG KO cells and WT cells, and that loss of genes involved in Okazaki fragment ligation induced S phase pADPr signaling. In a panel of human ovarian cancer cell lines, PARGi sensitivity was found to correlate with low levels of PARG mRNA, and they showed that the PARGi sensitivity of cells could be reduced by PARPi treatment. Finally, they addressed the conundrum of why PARG KO cells should be sensitive to a specific PARG inhibitor if there is no PARG to inhibit and found that the PARG KO cells had significant residual PARG activity when measured in a lysate activity assay, which could be inhibited by PARGi, although the inhabited PARG activity levels remained higher than those of PARG cKO cells (see below). This led them to generate new, more complete PARG KO cells they called complete/conditional KO (cKO), whose survival required the inclusion of the olaparib PARPi in the growth medium. These PARG cKO cells exhibited extremely low levels of PARG activity in vitro, consistent with a true PARG KO phenotype.

We thank this reviewer for his/her constructive comments and suggestions.

The finding that human ovarian cancer cells with low levels of PARG are more sensitive to inhibition with a small molecule PARG inhibitor, presumably due to the accumulation of high levels of protein PARylation (pADPr) that are toxic to cells is quite interesting, and this could be useful in the future as a diagnostic marker for preselection of ovarian cancer patients for treatment with a PARG inhibitor drug. The finding that loss of base excision repair (BER) and DNA repair genes led to increased PARylation and PARGi sensitivity is in keeping with the conclusion that PARG activity is essential for cell fitness, because it prevents excessive protein PARylation. The observation that increased PARylation can be detected in an unperturbed S phase in PARG KO cells is also of interest. However, the functional importance of protein PARylation at the replication fork in the normal cell cycle was not fully investigated, and none of the key PARylation targets for PARG required for S phase progression were identified. Overall, there are some interesting findings in the paper, but their impact is significantly lessened by the confusing way in which the paper has been organized and written, and this needs to be rectified.

We believe that PARP1 is one of the major relevant PARG substrates in S phase cells. Previous studies reported that PARP1 recognizes unligated Okazaki fragments and induces S phase PARylation, which recruits single-strand break repair proteins such as XRCC1 and LIG3 that acts as a backup pathway for Okazaki fragment maturation (Hanzlikova et al., 2018; Kumamoto et al., 2021). In this study, we revealed that accumulation of PARP1/2-dependent S phase PARylation eventually led to cell death (Fig. 2). Furthermore, we found that chromatin-bound PARP1 as well as PARylated PARP1 increased in PARG KO cells (Fig. S4A and Fig. 4A), suggesting that PARP1 is one of the key substrates of PARG in S phase cells. Of course, PARG may have additional substrates besides PARP1 which are required for its roles in S phase progression, as PARG is known to be recruited to DNA damage sites through pADPr- and PCNA-dependent mechanisms (Mortusewicz et al., 2011). Precisely how PARG regulates S phase progression warrants further investigation.

As suggested, we will revise our manuscript accordingly and provide additional explanation/statement upfront to avoid any misunderstandings.