Peer review process

Revised: This Reviewed Preprint has been revised by the authors in response to the previous round of peer review; the eLife assessment and the public reviews have been updated where necessary by the editors and peer reviewers.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorTony HunterSalk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, United States of America

- Senior EditorTony YuenIcahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, United States of America

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary:

In this manuscript Nie et al investigate the effect of PARG KO and PARG inhibition (PARGi) on pADPR, DNA damage, cell viability and synthetic lethal interactions in HEK293A and Hela cells. Surprisingly, the authors report that PARG KO cells are sensitive to PARGi and show higher pADPR levels than PARG KO cells, which is abrogated upon deletion or inhibition of PARP1/PARP2. The authors explain the sensitivity of PARG KO to PARGi through incomplete PARG depletion and demonstrate complete loss of PARG activity when incomplete PARG KO cells are transfected with additional gRNAs in the presence of PARPi. Furthermore, the authors show that the sensitivity of PARG KO cells to PARGi is not caused by NAD depletion but by S-phase accumulation of pADPR on chromatin coming from unligated Okazaki fragments, which are recognized and bound by PARP1. Consistently, PARG KO or PARG inhibition show synthetic lethality with Pol beta, which is required for Okazaki fragment maturation. PARG expression levels in ovarian cancer cell lines correlate negatively with their sensitivity to PARGi.

Strengths:

The authors show that PARG is essential for removing ADP-ribosylation in S-phase.

Weaknesses:

- This begs the question as to the relevant substrates of PARG in S-phase, which could be addressed, for example, by analysing PARylated proteins associated with replication forks in PARG-depleted cells (EdU pulldown and Af1521 enrichment followed by mass spectrometry).

- The results showing the generation of a full PARG KO should be moved to the beginning of the Results section, right after the first Results chapter (PARG depletion leads to drastic sensitivity to PARGi), otherwise the reader is left to wonder how PARG KO cells can be sensitive to PARGi when there should be presumably no PARG present.

- Please indicate in the first figure which isoforms were targeted with gRNAs, given that there are 5 PARG isoforms. You should also highlight that the PARG antibody only recognizes the largest isoform, which is clearly absent in your PARG KO, but other isoforms may still be produced, depending on where the cleavage sites were located.

- FACS data need to be quantified. Scatter plots can be moved to Supplementary while quantification histograms with statistical analysis should be placed in the main figures.

- All colony formation assays should be quantified and sensitivity plots should be shown next to example plates.

- Please indicate how many times each experiment was performed independently and include statistical analysis.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In the revised version the authors have addressed some of the reviewers' concerns, but, despite the new explanatory paragraph on page 16, the paper remains confusing because as shown in Figure 7 at the end of the Results the PARG KO 293A cells that were analyzed at the beginning of the Results are not true PARG knockouts. The authors stated that they did not rewrite the Results because they wanted to describe the experiments in the order in which they were carried out, but there is no imperative for the experiments to be described in the order in which they were done, and it would be much easier for the uninitiated reader to appreciate the significance of these studies if the true PARG KO cell data were presented at the beginning, as all three of the original reviewers proposed.

While the authors have to some extent clarified the nature of the PARG KO alleles, they have not been able to identify the source of the residual PARG activity in the PARG KO cells, in part because different commercial PARG antibodies give different and conflicting immunoblotting results. Additional sequence characterization of PARG mRNAs expressed in the PARG cKO cells, and also in-depth proteomic analysis of the different PARG bands could provide further insight into the origins and molecular identities of the various PARG proteins expressed from the different KO PARG alleles, and determine which of them might retain catalytic activity.

The authors have made no progress in identifying which are the key PARG substrates required for S phase progression, although they suggest that PARP1 itself may be an important target.

Author Response

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

eLife assessment

The authors' finding that PARG hydrolase removal of polyADP-ribose (PAR) protein adducts generated in response to the presence of unligated Okazaki fragments is important for S-phase progression is potentially valuable, but the evidence is incomplete, and identification of relevant PARylated PARG substrates in S-phase is needed to understand the role of PARylation and dePARylation in S-phase progression. Their observation that human ovarian cancer cells with low levels of PARG are more sensitive to a PARG inhibitor, presumably due to the accumulation of high levels of protein PARylation, suggests that low PARG protein levels could serve as a criterion to select ovarian cancer patients for treatment with a PARG inhibitor drug.

Thank you for the assessment and summary. Please see below for details as we have now addressed the deficiencies pointed out by the reviewers.

We believe that PARP1 is one of the major relevant PARG substrates in S phase cells. Previous studies reported that PARP1 recognizes unligated Okazaki fragments and induces S phase PARylation, which recruits single-strand break repair proteins such as XRCC1 and LIG3 that acts as a backup pathway for Okazaki fragment maturation (Hanzlikova et al., 2018; Kumamoto et al., 2021). In this study, we revealed that accumulation of PARP1/2-dependent S phase PARylation eventually led to cell death (Fig. 2). Furthermore, we found that chromatin-bound PARP1 as well as PARylated PARP1 increased in PARG KO cells (Fig. S4A and Fig. 4A), suggesting that PARP1 is one of the key substrates of PARG in S phase cells. Of course, PARG may have additional substrates besides PARP1 which are required for its roles in S phase progression, as PARG is known to be recruited to DNA damage sites through pADPr- and PCNA-dependent mechanisms (Mortusewicz et al., 2011). Precisely how PARG regulates S phase progression warrants further investigation.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

I have a major conceptual problem with this manuscript: How can the full deletion of a gene (PARG) sensitize a cell to further inhibition by its chemical inhibitor (PARGi) since the target protein is fully absent?

Please see below for details about this point. Briefly, we found that PARG is an essential gene (Fig. 7). There was residual PARG activity in our PARG KO cells, although the loss of full-length PARG was confirmed by Western blotting and DNA sequencing (Fig. S9). The residual PARG activity in these cells can be further inhibited by PARG inhibitor, which eventually lead to cell death.

The authors state in the discussion section: "The residual PARG dePARylation activity observed in PARG KO cells likely supports cell growth, which can be further inhibited by PARGi". What does this statement mean? Is the authors' conclusion that their PARG KOs are not true KOs but partial hypomorphic knockdowns? Were the authors working with KO clones or CRISPR deletion in populations of cells?

The reviewer is correct that our PARG KOs are not true KOs. We were working with CRISPR edited KO clones. As shown in this manuscript, we validated our KO clones by Western blotting, DNA sequencing and MMS-induced PARylation. Despite these efforts and our inability to detect full-length PARG in our KO clones, we suspect that our PARG KO cells may still express one or more active fragments of PARG due to alternative splicing and/or alternative ATG usage.

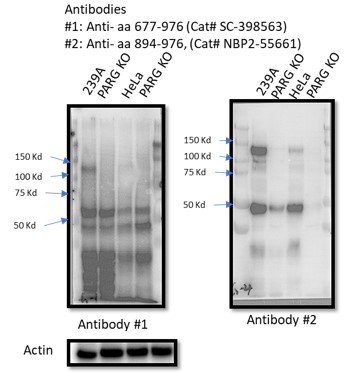

As shown in Fig. 7, we believe that PARG is essential for proliferation. Our initial KO cell lines are not complete PARG KO cells and residual PARG activity in these cells could support cell proliferation. Unfortunately, due to lack of appropriate reagents we could not draw solid conclusions regarding the isoforms or the truncated PARG expressed in these cells (Please see Western blots below).

Are there splice variants of PARG that were not knocked down? Are there PARP paralogues that can complement the biochemical activity of PARG in the PARG KOs? The authors do not discuss these critical issues nor engage with this problem.

There are five reviewed or potential PARG isoforms identified in the Uniprot database. The two sgRNAs (#1 and #2) used to generate initial PARG KO cells in this manuscript target all three catalytically active isoforms (isoforms 1, 2 and 3), and sgRNA#2 used in HeLa cells also targets isoforms 4 and 5, but these isoforms are considered catalytically inactive according to the Uniprot database. However, it is likely that sgRNA-mediated genome editing may lead to the creation of new alternatively spliced PARG mRNAs or the use of alternative ATG, which can produce catalytically active forms of PARG. Instead of searching for these putative spliced PARG RNAs, we used two independent antibodies that recognize the C-terminus of PARG for WB as shown below. Unfortunately, besides full-length PARG, these antibodies also recognized several other bands, some of them were reduced or absent in PARG KO cells, others were not. Thus, we could not draw a clear conclusion which functional isoform was expressed in our PARG KO cells. Nevertheless, we directly measured PARG activity in PARG KO cells (Fig. S9) and showed that we were still able to detect residual PARG activity in these PARG KO cells. These data clearly indicate that residual PARG activity are present and detected in our KO cells, but the precise nature of these truncated forms of PARG remains elusive.

Author response image 1.

These issues have to be dealt with upfront in the manuscript for the reader to make sense of their work.

We thank this reviewer for his/her constructive comments and suggestions. We will include the data above and additional discussion upfront in our revised manuscript to avoid any further confusion by our readers.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary:

In this manuscript, Nie et al investigate the effect of PARG KO and PARG inhibition (PARGi) on pADPR, DNA damage, cell viability, and synthetic lethal interactions in HEK293A and Hela cells. Surprisingly, the authors report that PARG KO cells are sensitive to PARGi and show higher pADPR levels than PARG KO cells, which are abrogated upon deletion or inhibition of PARP1/PARP2. The authors explain the sensitivity of PARG KO to PARGi through incomplete PARG depletion and demonstrate complete loss of PARG activity when incomplete PARG KO cells are transfected with additional gRNAs in the presence of PARPi. Furthermore, the authors show that the sensitivity of PARG KO cells to PARGi is not caused by NAD depletion but by S-phase accumulation of pADPR on chromatin coming from unligated Okazaki fragments, which are recognized and bound by PARP1. Consistently, PARG KO or PARG inhibition shows synthetic lethality with Pol beta, which is required for Okazaki fragment maturation. PARG expression levels in ovarian cancer cell lines correlate negatively with their sensitivity to PARGi.

Thank you for your nice comments. The complete loss of PARG activity was observed in PARG complete/conditional KO (cKO) cells. These cKO clones were generated using wild-type cells transfected with sgRNAs targeting the catalytic domain of PARG in the presence of PARP inhibitor.

Strengths:

The authors show that PARG is essential for removing ADP-ribosylation in S-phase.

Thanks!

Weaknesses:

- This begs the question as to the relevant substrates of PARG in S-phase, which could be addressed, for example, by analysing PARylated proteins associated with replication forks in PARG-depleted cells (EdU pulldown and Af1521 enrichment followed by mass spectrometry).

We believe that PARP1 is one of the major relevant PARG substrates in S phase cells. Previous studies reported that PARP1 recognizes unligated Okazaki fragments and induces S phase PARylation, which recruits single-strand break repair proteins such as XRCC1 and LIG3 that acts as a backup pathway for Okazaki fragment maturation (Hanzlikova et al., 2018; Kumamoto et al., 2021). In this study, we revealed that accumulation of PARP1/2-dependent S phase PARylation eventually led to cell death (Fig. 2). Furthermore, we found that chromatin-bound PARP1 as well as PARylated PARP1 increased in PARG KO cells (Fig. S4A and Fig. 4A), suggesting that PARP1 is one of the key substrates of PARG in S phase cells. Of course, PARG may have additional substrates besides PARP1 which are required for its roles in S phase progression, as PARG is known to be recruited to DNA damage sites through pADPr- and PCNA-dependent mechanisms (Mortusewicz et al., 2011). Precisely how PARG regulates S phase progression warrants further investigation.

- The results showing the generation of a full PARG KO should be moved to the beginning of the Results section, right after the first Results chapter (PARG depletion leads to drastic sensitivity to PARGi), otherwise, the reader is left to wonder how PARG KO cells can be sensitive to PARGi when there should be presumably no PARG present.

Thank you for your suggestion! However, we would like to keep the complete PARG KO result at the end of the Results section, since this was how this project evolved. Initially, we did not know that PARG is an essential gene. Thus, we speculated that PARGi may target not only PARG but also a second target, which only becomes essential in the absence of PARG. To test this possibility, we performed FACS-based and cell survival-based whole-genome CRISPR screens (Fig. 5). However, this putative second target was not revealed by our CRISPR screening data (Fig. 5). We then tested the possibility that these cells may have residual PARG expression or activity and only cells with very low PARG expression are sensitive to PARGi, which turned out to be the case for ovarian cancer cells. Equipped with PARP inhibitor and sgRNAs targeting the catalytic domain of PARG, we finally generated cells with complete loss of PARG activity to prove that PARG is an essential gene (Fig. 7). This series of experiments underscore the challenge of validating any KO cell lines, i.e. the identification of frame-shift mutations, absence of full-length proteins, and phenotypic changes may still not be sufficient to validate KO clones. This is an important lesson we learned and we would like to share it with the scientific community.

To avoid further misunderstanding, we will include additional statements/comments at the end of “PARG depletion leads to drastic sensitivity to PARGi” section and at the beginning of “CRISPR screens reveal genes responsible for regulating pADPr signaling and/or cell lethality in WT and PARG KO cells”. Hope that our revised manuscript will make it clear.

- Please indicate in the first figure which isoforms were targeted with gRNAs, given that there are 5 PARG isoforms. You should also highlight that the PARG antibody only recognizes the largest isoform, which is clearly absent in your PARG KO, but other isoforms may still be produced, depending on where the cleavage sites were located.

The two sgRNAs (#1 and #2) used to generate initial PARG KO cells in this manuscript target all three catalytically active isoforms (isoforms 1, 2 and 3), and sgRNA#2 used in HeLa cells also targets isoforms 4 and 5, but these isoforms are considered catalytically inactive according to the Uniprot database. As suggested, we will modify Fig. S1D and the figure legends.

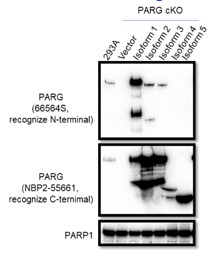

The manufacturer instruction states that the Anti-PARG antibody (66564S) can only recognize isoform 1, this antibody could recognize isoforms 2 and 3 albeit weakly based on Western blot results with lysates prepared from PARG cKO cells reconstituted with different PARG isoforms, as shown below. As suggested, we will add a statement in the revised manuscript and provide the Western blotting data below.

Author response image 2.

To test whether other isoforms were expressed in 293A and/or HeLa cells, we used two independent antibodies that recognize the C-terminus of PARG for WB as shown below. Unfortunately, besides full-length PARG, these antibodies also recognized several other bands, some of them were reduced or absent in PARG KO cells, others were not. Thus, we could not draw a clear conclusion which functional isoforms or truncated forms were expressed in our PARG KO cells.

Author response image 3.

- FACS data need to be quantified. Scatter plots can be moved to Supplementary while quantification histograms with statistical analysis should be placed in the main figures.

We agree with this reviewer that quantification of FACS data may provide straightforward results in some of our data. However, it is challenging to quantify positive S phase pADPr signaling in some panels, for example in Fig. 3A and Fig. 4C. In both panels, pADPr signaling was detected throughout the cell cycle and therefore it is difficult to know the percentage of S phase pADPr signaling in these samples. Thus, we decide to keep the scatter plots to demonstrate the dramatic and S phase-specific pADPr signaling in PARG KO cells treated with PARGi. We hope that these data are clear and convincing even without any quantification.

- All colony formation assays should be quantified and sensitivity plots should be shown next to example plates.

As suggested, we will include the sensitivity plot next to Fig. 3D. However, other colony formation assays in this study were performed with a single concentration of inhibitor and therefore we will not provide sensitivity plots for these experiments. Nevertheless, the results of these experiments are straightforward and easy to interpret.

- Please indicate how many times each experiment was performed independently and include statistical analysis.

As suggested, we will add this information in the revised manuscript.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Here the authors carried out a CRISPR/sgRNA screen with a DDR gene-targeted mini-library in HEK293A cells looking for genes whose loss increased sensitivity to treatment with the PARG inhibitor, PDD00017273 (PARGi). Surprisingly they found that PARG itself, which encodes the cellular poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolase (dePARylation) enzyme, was a major hit. Targeted PARG KO in 293A and HeLa cells also caused high sensitivity to PARGi. When PARG KO cells were reconstituted with catalytically-dead PARG, MMS treatment caused an increase in PARylation, not observed when cells were reconstituted with WT PARG or when the PARG KO was combined with PARP1/2 DKO, suggesting that loss of PARG leads to a strong PARP1/2-dependent increase in protein PARylation. The decrease in intracellular NADH+, the substrate for PARP-driven PARylation, observed in PARG KO cells was reversed by treatment with NMN or NAM, and this treatment partially rescued the PARG KO cell lethality. However, since NAD+ depletion with the FK868 nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) inhibitor did not induce a similar lethality the authors concluded that NAD+ depletion/reduction was only partially responsible for the PARGi toxicity. Interestingly, PARylation was also observed in untreated PARG KO cells, specifically in S phase, without a significant rise in γH2AX signals. Using cells synchronized at G1/S by double thymidine blockade and release, they showed that entry into S phase was necessary for PARGi to induce PARylation in PARG KO cells. They found an increased association of PARP1 with a chromatin fraction in PARG KO cells independent of PARGi treatment, and suggested that PARP1 trapping on chromatin might account in part for the increased PARGi sensitivity. They also showed that prolonged PARGi treatment of PARG KO cells caused S phase accumulation of pADPr eventually leading to DNA damage, as evidenced by increased anti-γH2AX antibody signals and alkaline comet assays. Based on the use of emetine, they deduced that this response could be caused by unligated Okazaki fragments. Next, they carried out FACS-based CRISPR screens to identify genes that might be involved in cell lethality in WT and PARG KO cells, finding that loss of base excision repair (BER) and DNA repair genes led to increased PARylation and PARGi sensitivity, whereas loss of PARP1 had the opposite effects. They also found that BER pathway disruption exhibited synthetic lethality with PARGi treatment in both PARG KO cells and WT cells, and that loss of genes involved in Okazaki fragment ligation induced S phase pADPr signaling. In a panel of human ovarian cancer cell lines, PARGi sensitivity was found to correlate with low levels of PARG mRNA, and they showed that the PARGi sensitivity of cells could be reduced by PARPi treatment. Finally, they addressed the conundrum of why PARG KO cells should be sensitive to a specific PARG inhibitor if there is no PARG to inhibit and found that the PARG KO cells had significant residual PARG activity when measured in a lysate activity assay, which could be inhibited by PARGi, although the inhabited PARG activity levels remained higher than those of PARG cKO cells (see below). This led them to generate new, more complete PARG KO cells they called complete/conditional KO (cKO), whose survival required the inclusion of the olaparib PARPi in the growth medium. These PARG cKO cells exhibited extremely low levels of PARG activity in vitro, consistent with a true PARG KO phenotype.

We thank this reviewer for his/her constructive comments and suggestions.

The finding that human ovarian cancer cells with low levels of PARG are more sensitive to inhibition with a small molecule PARG inhibitor, presumably due to the accumulation of high levels of protein PARylation (pADPr) that are toxic to cells is quite interesting, and this could be useful in the future as a diagnostic marker for preselection of ovarian cancer patients for treatment with a PARG inhibitor drug. The finding that loss of base excision repair (BER) and DNA repair genes led to increased PARylation and PARGi sensitivity is in keeping with the conclusion that PARG activity is essential for cell fitness, because it prevents excessive protein PARylation. The observation that increased PARylation can be detected in an unperturbed S phase in PARG KO cells is also of interest. However, the functional importance of protein PARylation at the replication fork in the normal cell cycle was not fully investigated, and none of the key PARylation targets for PARG required for S phase progression were identified. Overall, there are some interesting findings in the paper, but their impact is significantly lessened by the confusing way in which the paper has been organized and written, and this needs to be rectified.

We believe that PARP1 is one of the major relevant PARG substrates in S phase cells. Previous studies reported that PARP1 recognizes unligated Okazaki fragments and induces S phase PARylation, which recruits single-strand break repair proteins such as XRCC1 and LIG3 that acts as a backup pathway for Okazaki fragment maturation (Hanzlikova et al., 2018; Kumamoto et al., 2021). In this study, we revealed that accumulation of PARP1/2-dependent S phase PARylation eventually led to cell death (Fig. 2). Furthermore, we found that chromatin-bound PARP1 as well as PARylated PARP1 increased in PARG KO cells (Fig. S4A and Fig. 4A), suggesting that PARP1 is one of the key substrates of PARG in S phase cells. Of course, PARG may have additional substrates besides PARP1 which are required for its roles in S phase progression, as PARG is known to be recruited to DNA damage sites through pADPr- and PCNA-dependent mechanisms (Mortusewicz et al., 2011). Precisely how PARG regulates S phase progression warrants further investigation.

As suggested, we will revise our manuscript accordingly and provide additional explanation/statement upfront to avoid any misunderstandings.

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations For The Authors):

- Figure 1c. Why does the viability of PARG KO cells improve at higher doses of PARGi? How do the authors explain this paradox?

This phenomenon was observed in 293A PARG KO cells and happened in CellTiter-Glo assay, especially with the top three PARGi concentrations (100 µM, 33.33 µM and 11.11 µM). This may due to the low solubility of this PARGi in the medium, since we sometimes observed precipitation at high concentrations when PARGi stock was diluted in medium.

- Figure 2d. The authors show that PARGi reduced NAD+ level by 20%. This reduction in NAD+ probably does not explain the cell death phenotype observed by parthanatos cell death. What pathway is activated by PARGi to induce cell death?

Since PARG KO cells treated with PARGi led to uncontrolled pADPr accumulation, it is possible that some of these cells may die due to parthanotos. However, we did not observe a dramatic reduction in NAD+ level. A previous study showed that Parg(-/-) mouse ES cells predominantly underwent caspase-dependent apoptosis (Shirai et al., 2013). Indeed, PARP1 cleavage was detected in PARG KO cells with prolonged PARGi treatment, indicating that at least some of these cells die due to apoptosis (Fig. 2A). Cytotoxicity of PARGi in PARG KO cells may due to several mechanisms including apoptosis, parthanatos and NAD+ reduction.

- The authors refer to FK866 in the text without explaining what this agent is. FK866 is a noncompetitive inhibitor of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAPRT), a key enzyme in the regulation of NAD+ biosynthesis from the natural precursor nicotinamide. The authors should explain experimental tools in the text as they use them for clarity to the reader.

Thanks for the suggestion! We will include additional citations and discuss how FK866 works in our revised manuscript.

- In addition to these issues, there are significant formatting and textual problems, such that there are multiple gaps in the body of the text that make coherent reading of the manuscript impossible. Examples are: Page 3 line 10. Page 6 line 5 and line 15, Page 7 line 2, 3, and line 8. Page 8, line 1, and line 3 from bottom. Page 9 line 1, line 7 from bottom and line 9 from the bottom, Page 18 of the results in several places, etc. etc. etc. These formatting errors convey the impression that the submitting authors did not adequately review the manuscript for technical problems prior to submission. The authors need to correct these errors.

Sorry, we will edit the text and remove these gaps as suggested.

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations For The Authors):

- The major problem with this paper is conceptual - namely, how could PARG knockout cells be hypersensitive to a selective PARG small molecular inhibitor. The evidence in Figure 7 that there is measurable residual PARG activity in the so-called PARG KO 293A and HeLa cells provides a partial explanation for why PARG inhibitor treatment might be deleterious to the PARG KO cells, i.e., because PARGi blocks this residual PARG activity. However, although the authors characterized the PARG alleles in the 293A PARG KO cells by sequencing, the molecular origin of the significant level of residual PARG activity remains unclear (see points 7-9).

Yes, in our study we showed that PARGi treatment inhibited the residual PARG activity in PARG KO cells, which mimics complete loss of PARG as PARG is an essential gene. These data agree with a previous study using Parg(-/-) mouse cells (Koh et al., 2004).We attempted to define the molecular origin of the residual PARG activity, unfortunately this was challenging (please see below for additional discussions). Nevertheless, we showed that residual PARG activity could be detected in PARG KO cells and more importantly cells with reduced PARG expression or activity are sensitive to PARGi. These results indicate that PARG expression and/or activity may be used as a biomarker for PARGi-based therapy.

- Although the most obvious explanation for the PARGi sensitivity data presented in Figures 1-4 is that the PARG KO cells have residual PARG activity, the authors wait until the discussion on page 26 to raise the possibility that the PARG KO cells might have residual PARG activity that renders them sensitive to PARGi. It would be more logical to move the PARG activity data in Figure 7 earlier in the paper as a supplementary figure, so that the reader is not left wondering how a PARG KO cell remains sensitive to a PARG inhibitor. For this reason, it is recommended that the whole paper be reorganized and rewritten to provide a more logical flow that allows the reader to understand what was done, and why it is hard to generate complete PARG KO cells because the accumulation of pADPR adducts is toxic to the cell.

Thank you for your suggestion! However, we would like to keep the complete PARG KO result at the end of the Results section, since this was how this project evolved. Initially, we did not know that PARG is an essential gene. Thus, we speculated that PARGi may target not only PARG but also a second target, which only becomes essential in the absence of PARG. To test this possibility, we performed FACS-based and cell survival-based whole-genome CRISPR screens (Fig. 5). However, this putative second target was not revealed by our CRISPR screening data (Fig. 5). We then tested the possibility that these cells may have residual PARG expression or activity and only cells with very low PARG expression are sensitive to PARGi, which turned out to be the case for ovarian cancer cells. Equipped with PARP inhibitor and sgRNAs targeting the catalytic domain of PARG, we finally generated cells with complete loss of PARG activity to prove that PARG is an essential gene (Fig. 7). This series of experiments underscore the challenge of validating any KO cell lines, i.e. the identification of frame-shift mutations, absence of full-length proteins, and phenotypic changes may still not be sufficient to validate KO clones. This is an important lesson we learned and we would like to share it with the scientific community.

To avoid further misunderstanding, we will include additional statements/comments at the end of “PARG depletion leads to drastic sensitivity to PARGi” section and at the beginning of “CRISPR screens reveal genes responsible for regulating pADPr signaling and/or cell lethality in WT and PARG KO cells”. Hope that our revised manuscript will make it clear.

- Exactly how PARG activity would be coordinated with PARP1/2 activity during normal S phase to ensure that PARylation can serve its required function, whatever that may be, and is then removed by PARG is unclear - how would this be orchestrated at the level of a replication fork?

PARG is known to be recruited to sites of DNA damage through pADPr- and PCNA-dependent mechanisms (Mortusewicz et al., 2011). Our current hypothesis is that PARP1 is one of the major PARG substrates in S phase cells. Previous studies reported that PARP1 recognizes unligated Okazaki fragments and induces S phase PARylation, which recruits single-strand break repair proteins such as XRCC1 and LIG3 that acts as a backup pathway for Okazaki fragment maturation (Hanzlikova et al., 2018; Kumamoto et al., 2021). In this study, we revealed that accumulation of PARP1/2-dependent S phase PARylation eventually led to cell death (Fig. 2). Furthermore, we found that chromatin-bound PARP1 as well as PARylated PARP1 increased in PARG KO cells (Fig. S4A and Fig. 4A), suggesting that PARP1 is one of the key substrates of PARG in S phase cells. Of course, PARG may have additional substrates besides PARP1 which are required for its roles in S phase progression. Precisely how PARG regulates S phase progression warrants further investigation.

- Figure 2B: What gRNAs were used to generate the 293A and HeLa PARG knock clones, i.e., where are they located in the PARG gene? If they are not in the catalytic domain it might be possible to generate PARG proteins with N-terminal deletions that are still active (see points 8-10 below).

The two sgRNAs (#1 and #2) used to generate initial PARG KO cells in this manuscript target all three catalytically active isoforms (isoforms 1, 2 and 3), and sgRNA#2 used in HeLa cells also targets isoforms 4 and 5, but these isoforms are considered catalytically inactive according to the Uniprot database. As suggested, we will modify Fig. S1D and the figure legends to show the localization of gRNAs.

We agree with this reviewer that truncated but active forms of PARG exist in these KO cells. We attempted to identify these trunated forms of PARG by using two independent antibodies that recognize the C-terminus of PARG for WB as shown below. Unfortunately, besides full-length PARG, these antibodies also recognized several other bands, some of them were reduced or absent in PARG KO cells, others were not. Thus, we could not draw a clear conclusion which functional isoform/truncated form was expressed in our PARG KO cells. Nevertheless, we directly measured PARG activity in PARG KO cells (Fig. S9) and showed that we were still able to detect residual PARG activity in these PARG KO cells. Based on these results, we stated that the residual PARG activity was detected in our KO cells, but we were not able to specify the truncated variants of PARG in these cells.

Author response image 4.

- Figure 3B/page 19: The authors state that "emetine, which diminishes Okazaki fragments, greatly inhibited S phase pADPr signaling in PARG KO cells", and from this deduced that Okazaki fragments on the lagging strand activate PARylation. However, emetine is not a specific lagging strand synthesis inhibitor, as implied here, but rather a protein synthesis inhibitor, which inhibits Okazaki fragment formation indirectly (see PMID: 36260751). The authors need to rewrite this section to explain how emetine works in this context.

As suggested, we will cite this reference and discuss how emetine inhibits Okazaki fragment maturation in our revised manuscript. Additionally, we used three different POLA1 inhibitors to diminish Okazaki fragments. As shown in Fig. S3B, all three POLA1 inhibitors significantly abolished S-phase pADPr induced by PARGi in PARG KO cells. Furthermore, POLA1 inhibitors, adarotene and CD437, were able to rescue cell lethality caused by PARGi in PARG KO cells (Fig. 3E).

- Figure 7: It is not clear why these cells are called PARG complete/conditional KO cells (cKO). Generally, "conditional knockout" refers to a cell or animal in which a gene can be conditionally knocked out by inducible expression of Cre. Here, it appears that "conditional" refers to the fact that the PARG KO cells only grow in the presence of olaparib - is this the case?

Yes, we used the name to separate these cells from our initial PARG KO cells. Moreover, we were only able to obtain and maintain these PARG cKO clones with complete loss of PARG activity in the presence of PARP inhibitor. Therefore, we called them PARG complete/conditional KO (cKO) cells.

- Figure 7B and D: The level of full-length PARG protein was much lower in the 293A and HeLa cKO cells compared to WT cells consistent with cKO cells representing a more complete PARG KO. The level of PARG protein in the 293A PARG cKO cells was apparently also lower than in the original PARG KO cells, but the KO and cKO samples should be run side by side to demonstrate this conclusively, and the bands need to be quantified. In panel B, it is not clear from the legend what cKO_3 and cKO_4 are, but presumably, they are different clones, and this should be stated.

Full-length PARG was not detected in either PARG KO or PARG cKO cells by WB. The apparent lower level of endogenous PARG in Fig. 7D was due to the fact that reconstituted cells had high exogenous PARG expression and therefore we had to reduce exposure time for WB.

As for cKO_3 and cKO_4 in Fig.7, they are different clones created by different sgRNAs. As suggested, we will include additional information in figure legends to clearly state which sgRNA was used to generate the respective KO and cKO clones.

- Figure S8: There is not enough information here or in the text to allow the reader to interpret these PARG allele sequences obtained from the PARG KO cells. From the Methods section, it appears that the PARG KO cells were clonal, with sequence data from one clone of each of the 293A and HeLa cell PARG KO cells being shown. If this is right, then in both cell types one out of four PARG alleles is wild type, and therefore one would expect the PARG protein signal to be ~25% of that in WT cells. However, based on the 293A PARG KO cells PARG immunoblot in Figure 2B the PARG protein signal is clearly much lower than 25% (these bands need to be quantified), and this discrepancy needs to be explained. What is the level of PARG protein in the PARG KO HeLa cells? If different PARG KO cell clones are analyzed by sequencing, do they all have an apparently intact PARG allele? Four different gRNA target sites in the PARG gene are shown in panel A in Figure 7, but the description in the text regarding how the four gRNAs were used is totally inadequate - were all four used simultaneously or only the two in the catalytic domain? Were pairs of gRNAs used in an attempt to generate a large intervening deletion - some Southern blots of the PARG gene region in the PARG cKO cells are needed to figure this out. The gRNAs are given numbers in Figure 7A, but it is unclear from the sequences shown in Figures S8 and S9 which gRNA sites are shown. All of this has to be clarified, so that the reader can understand the nature of the KO/cKO cells knockout alleles, and what PARG-related products, if any, they can express.

Yes, all KO and cKO cells used in this study are single clones. As suggested, we will revise figure legends in Fig.7, S8 and S9 to include detailed information. To avoid any further misunderstanding, we will label the allele “WT” to “WT (reference)” in Fig. S8 and S9. We did not detect intact/wild-type PARG sequence in any single KO/cKO clone by DNA sequencing. Sequencing of single KO/cKO clones was performed by using TOP TA Cloning kit. Briefly, genomic DNA was extracted from each single KO/cKO clone. Approximately 300bp surrounding the sgRNA targeting sequence was amplified by PCR. The PCR product was cloned into the vector and approximately 10-15 bacteria clones were extracted and sent for sequencing. If any intact/wild-type PARG sequence was detected in these 10-15 bacteria clones, this KO/cKO clone was considered heterozygous clone and discarded.

HEK293A and HeLa cells are not diploid cells and have complex karyotypes. PARG gene is located on chromosome 10. Karyotyping by M-FISH shows that HeLa cells have 3 copies of chromosome 10 (Landry et al., 2013). HEK293 cells predominantly have 3 copies of chromosome 10 and sometimes 4 copies can be detected by G-banding (Binz et al., 2019). Therefore, it is anticipated that 1 to 4 mutant alleles would be detected in each KO/cKO clone by sequencing.

Only one sgRNA was transfected into cells for the selection of single clones. We did not use paired or multiple sgRNAs in any of these experiments. As shown in Fig. S1D and Fig. 7A, HEK293A derived and HeLa derived PARG KO single clones were generated with the use of different sgRNAs. In addition, the two PARG cKO single clones from HEK293A and HeLa cells were also generated by the use of two different sgRNAs, as shown in Fig. 7A-B. We will include all the information above in the revised manuscript, i.e. in Methods section as well as in figure legends.

- Figure S9A: The sequences of the 293A PARG alleles in the cKO cells suggest that these cells also have one intact PARG allele, which again does not fit with the very low level of intact PARG protein shown in Figure 7B. How do the authors explain this?

Sorry, this is a misunderstanding. The allele “WT” in Fig. S8 and S9 is the reference sequence. We will change it to “Reference sequence” to avoid further confusion. As mentioned above, we did not detect any intact/wild-type PARG sequence in any of our single KO/cKO clones by sequencing.

- Figure S9B: These critical lysate activity data show that the PARG KO cells have ~50% of the PARG activity detected in WT cells. However, this is not consistent with the PARG protein level detected in PARG immunoblot in Figure 1B, which appears to be less than 5% of the PARG protein level in WT cells (with one intact PARG allele in these cells one would theoretically expect~ 25%, although this depends on whether all four alleles are expressed equally). One possibility is that active PARG fragments are generated from one or more of the PARG KO alleles in the PARG KO cells. Targeted sequencing of PARG mRNAs might reveal whether there are shorter RNAs that could encode a protein containing the C-terminal catalytic domain (aa 570-910). In addition, the authors need to show the entire immunoblot to determine if there are smaller proteins recognized by the anti-PARG antibodies that might represent shorter PARG gene products (for this we need to know where the epitope against which the PARG antibodies are directed are located within the PARG protein - ideally they authors need to use an antibody directed against an epitope near the C-terminus).

As stated in the Methods section, we incubated cell lysates with substrates overnight to evaluate the maximum level of pADPr hydrolysis, i.e. PARG activity, we were able to detect in this assay. It is very likely that the PARG activity in PARG KO cells was much lower than 50%, due to saturation of signals for lysates isolated from wild-type cells. Thus, the data presented in our manuscript probably underestimate the reduction of PARG activity in PARG KO cells. Nevertheless, these data indicate that residual PARG activity was detected in PARG KO cells, however this activity was absent in PARG cKO cells.

As aforementioned, we used two independent antibodies that recognize the C-terminus of PARG for WB. Unfortunately, we could not draw a clear conclusion which functional isoforms or truncated proteins were expressed in our PARG KO cells. The dePARylation assay used here may be the best way to test the residual PARG activity in our KO and cKO cells.

- Figure 7D: In this experiment, the level of re-expressed WT PARG protein was much higher than that of the endogenous PARG protein (quantification is needed) - how might this affect the interpretation of these experiments (N.B., WT and catalytically-dead PARG were also re-expressed for the experiments shown in Figure 1, but there are no PARG immunoblots to demonstrate how much the exogenous proteins were overexpressed, or activity measurements). If regulated pADPr signaling is important for a normal S phase, then one would have thought that expressing a very high level of active PARG would create problems.

In Fig. S1E, we blotted endogenous PARG level in control cells and exogenous PARG level in reconstituted cells. The reviewer is correct that exogenous PARG expression was much higher (~10-fold) than that of endogenous PARG in WT control cells. Nevertheless, we did not observe any obvious phenotypes in PARG KO/cKO cells reconstituted with high level of exogeneous PARG, which may reflect excess PARG level/activity in wild-type control cells.

References:

Binz, R. L., Tian, E., Sadhukhan, R., Zhou, D., Hauer-Jensen, M., and Pathak, R. (2019). Identification of novel breakpoints for locus- and region-specific translocations in 293 cells by molecular cytogenetics before and after irradiation. Sci Rep 9, 10554.

Hanzlikova, H., Kalasova, I., Demin, A. A., Pennicott, L. E., Cihlarova, Z., and Caldecott, K. W. (2018). The Importance of Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase as a Sensor of Unligated Okazaki Fragments during DNA Replication. Mol Cell 71, 319-331 e313.

Koh, D. W., Lawler, A. M., Poitras, M. F., Sasaki, M., Wattler, S., Nehls, M. C., Stoger, T., Poirier, G. G., Dawson, V. L., and Dawson, T. M. (2004). Failure to degrade poly(ADP-ribose) causes increased sensitivity to cytotoxicity and early embryonic lethality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 17699-17704.

Kumamoto, S., Nishiyama, A., Chiba, Y., Miyashita, R., Konishi, C., Azuma, Y., and Nakanishi, M. (2021). HPF1-dependent PARP activation promotes LIG3-XRCC1-mediated backup pathway of Okazaki fragment ligation. Nucleic Acids Res 49, 5003-5016.

Landry, J. J., Pyl, P. T., Rausch, T., Zichner, T., Tekkedil, M. M., Stutz, A. M., Jauch, A., Aiyar, R. S., Pau, G., Delhomme, N., et al. (2013). The genomic and transcriptomic landscape of a HeLa cell line. G3 (Bethesda) 3, 1213-1224.

Mortusewicz, O., Fouquerel, E., Ame, J. C., Leonhardt, H., and Schreiber, V. (2011). PARG is recruited to DNA damage sites through poly(ADP-ribose)- and PCNA-dependent mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res 39, 5045-5056.

Shirai, H., Fujimori, H., Gunji, A., Maeda, D., Hirai, T., Poetsch, A. R., Harada, H., Yoshida, T., Sasai, K., Okayasu, R., and Masutani, M. (2013). Parg deficiency confers radio-sensitization through enhanced cell death in mouse ES cells exposed to various forms of ionizing radiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 435, 100-106.