Peer review process

Revised: This Reviewed Preprint has been revised by the authors in response to the previous round of peer review; the eLife assessment and the public reviews have been updated where necessary by the editors and peer reviewers.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorDavid Paz-GarciaCentro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste (CIBNOR), La Paz, Mexico

- Senior EditorAleksandra WalczakCNRS, Paris, France

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Summary:

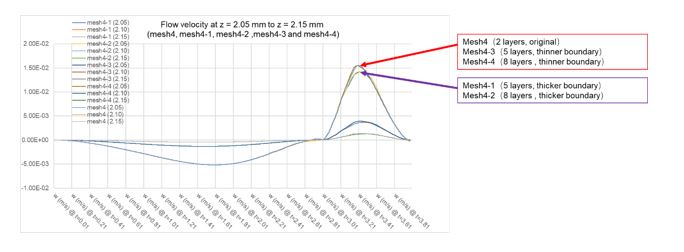

The authors utilize fluid-structure interaction analyses to simulate fluid flow within and around the Cambrian cnidarian Quadrapyrgites to reconstruct feeding/respiration dynamics. Based on vorticity and velocity flow patterns, the authors suggest that the polyp expansion and contraction ultimately develop vortices around the organism that are like what modern jellyfish employ for movement and feeding. Lastly, the authors suggest that this behavior is likely a prerequisite transitional form to swimming medusae.

Strengths:

While fluid-structure-interaction analyses are common in engineering, physics, and biomedical fields, they are underutilized in the biological and paleobiological sciences. Zhang et al. provide a strong approach to integrating active feeding dynamics into fluid flow simulations of ancient life. Based on their data, it is entirely likely the described vortices would have been produced by benthic cnidarians feeding/respiring under similar mechanisms. However, some of the broader conclusions require additional justification.

Weaknesses:

(1) The claim that olivooid-type feeding was most likely a prerequisite transitional form to jet-propelled swimming needs much more support or needs to be tailored to olivooids. This suggests that such behavior is absent (or must be convergent) before olivooids, which is at odds with the increasing quantities of pelagic life (whose modes of swimming are admittedly unconstrained) documented from Cambrian and Neoproterozoic deposits. Even among just medusozoans, ancestral state reconstruction suggests that they would have been swimming during the Neoproterozoic (Kayal et al., 2018; BMC Evolutionary Biology) with no knowledge of the mechanics due to absent preservation.

(2) While the lack of ambient flow made these simulations computationally easier, these organisms likely did not live in stagnant waters even within the benthic boundary layer. The absence of ambient unidirectional laminar current or oscillating current (such as would be found naturally) biases the results.

(3) There is no explanation for how this work could be a breakthrough in simulation gregarious feeding as is stated in the manuscript.

Despite these weaknesses the authors dynamic fluid simulations convincingly reconstruct the feeding/respiration dynamics of the Cambrian Quadrapyrgites, though the large claims of transitionary stages for this behavior are not adequately justified. Regardless, the approach the authors use will be informative for future studies attempting to simulate similar feeding and respiration dynamics.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary:

The authors seek to elucidate the early evolution of cnidarians through computer modeling of fluid flow in the oral region of very small, putative medusozoan polyps. They propose that the evolutionary advent of the free-swimming medusoid life stage was preceded by a sessile benthic life stage equipped with circular muscles that originally functioned to facilitate feeding and that later became co-opted for locomotion through jet propulsion.

Strengths:

Assumptions of the modeling exercise laid out clearly; interpretations of the results of the model runs in terms of functional morphology plausible. An intriguing investigation that should stimulate further discussion and research.

Weaknesses:

Speculation on the origin of the medusoid life stage in cnidarians heavily dependent on prior assumptions concerning the soft part anatomy and material properties of the skeleton of the modeled fossil organism that may be open to alternative interpretations. Logically, of course, the hypothesis that cnidarian medusae originated from benthic polyps must be evaluated along with the alternative hypotheses that the medusa came first and that the ancestral cnidarian exhibited both life stages.