Peer review process

Revised: This Reviewed Preprint has been revised by the authors in response to the previous round of peer review; the eLife assessment and the public reviews have been updated where necessary by the editors and peer reviewers.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorGoutham NarlaUniversity of Michigan, Ann Arbor, United States of America

- Senior EditorTony NgKing's College London, London, United Kingdom

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary:

The Meiri group previously showed that Notch1-activated human T-ALL cell lines are sensitive to a cannabis extract in vitro and in vivo (Ref. 32). In that article, the authors showed that Extract #12 reduced NICD expression and viability, which was partially rescued by restoring NICD expression. Here, the authors have identified three compounds of Extract #12 (CBD, 331-18A, and CBDV) that are responsible for the majority of anti-leukemic activity and NICD reduction. Using a pharmacological approach, the authors determined that Extract #12 exerted its anti-leukemic and NICD-reducing affects through the CB2 and TRPV1 receptors. To determine mechanism, the authors performed RNA-seq and observed that Extract #12 induces ER calcium depletion and stress-associated signals -- ATF4, CHOP, and CHAC1. Since CHAC1 was previously shown to be a Notch inhibitor in neural cells, the authors assume that the cannabis compounds repress Notch S1 cleavage through CHAC1 induction. The induction of stress-associated signals, Notch repression, and anti-leukemic effects were reversed by the integrated stress response (ISR) inhibitor ISRIB. Interestingly, combining the 3 cannabinoids gave synergistic anti-leukemic effects in vitro and had growth inhibitory effects in vivo.

Strengths:

(1) The authors show novel mechanistic insights that cannabinoids induce ER calcium release and that the subsequent integrated stress response represses activated NOTCH1 expression and kills T-ALL cells.

(2) This report adds to the evidence that phytocannabinoids can show a so-called "entourage effect" in which minor cannabinoids enhance the effect of the major cannabinoid CBD.

(3) This report dissects out the main cannabinoids in the previously described Extract #12 that contribute to T-ALL killing.

(4) The manuscript is clear and generally well-written.

(5) The data are mostly high quality and with adequate statistical analyses.

(6) The data generally support the authors' conclusions. The main exception is the experiments related to Notch.

(7) The authors' discovery of the role of the integrated stress response might explain previous observations that SERCA inhibitors block Notch S1 cleavage and activation in T-ALL (Roti Cancer Cell 2013). The previous explanation by Roti et al was that calcium depletion causes Notch misfolding, which leads to impaired trafficking and cleavage. Perhaps this explanation is not entirely sufficient?

Weaknesses:

(1) Given the authors' previous Cancer Communications paper on the anti-leukemic effects and mechanism of Extract #12, the significance of the original manuscript was reduced. To increase significance, the authors provided a new Fig. S7 in the revision showing that Extract #12 inhibits PDX growth in vivo. This experiment is nicely supportive of the anti-leukemic effects of Extract #12, raising the significance of their previous Cancer Communication paper by using in vivo patient-derived cells. However, this reviewer had suggested testing the combination of 333-18A+CBVD+CBD since the combination is the focus of the current manuscript. For unclear reasons, the combination was not tested.

(2) It would be important to connect the authors' findings and a wealth of literature on the role of ER calcium/stress on Notch cleavage, folding, trafficking, and activation. The several references suggested by this reviewer were not included in the revised manuscript for unclear reasons. These references are important to show the current status of the field and help readers appreciate what this manuscript brings that is new to T-ALL. In particular, Roti et al (Cancer Cell 2013) showed that SERCA inhibitors like thapsigardin reduce ER calcium levels and block Notch signaling by inhibiting NOTCH1 trafficking and inhibiting Furin-mediated (S1) cleavage of Notch1 in T-ALL. Multiple EGF repeats and all three Lin12/Notch repeats in the extracellular domains of Notch receptors require calcium for proper folding (Aster Biochemistry 1999; Gordon Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007; Hambleton Structure 2004; Rand Protein Sci 1997). Thus, Roti et al concluded that ER calcium depletion blocks NOTCH1 S1 cleavage in T-ALL. This effect seems to be conserved in Drosophila as Periz and Fortiin (EMBO J, 1999) showed impaired Notch cleavage in Ca2+/ATPase-mutated Drosophila cells.

(3) There is an overreliance of the data on single cell line -- MOLT4. MOLT4 is a good initial choice as it is Notch-mutated, Notch-dependent, and representative of the most common T-ALL subtype -- TAL1. However, there is no confirmatory data in other TAL1-positive T-ALLs or interrogation of other T-ALL subtypes. While this reviewer appreciates that the authors showed that multiple T-ALL cell lines were killed in response to Extract #12 in a previous study, the current manuscript is a separate study that should stand on its own. T-ALLs can be killed by multiple mechanisms. It would be important to show a few pieces of key data illustrating that the mechanism of killing found in MOLT4 applies to other T-ALLs.

(4) Fig. 6H. The effects of the cannabinoid combination might be statistically significant but seems biologically weak.

(5) Fig. 3. Based on these data, the authors conclude that the cannabinoid combination induces CHAC1, which represses Notch S1 cleavage in T-ALL cells. The concern is that Notch signaling is highly context dependent. CHAC1 might inhibit Notch in neural cells (Refs. 34-35), but it might not do this in a different context like T-ALL. It would be important to show evidence that CHAC1 represses S1 cleavage in the T-ALL context. More importantly, Fig. 3H clearly shows the cannabinoid combination inducing ATF4 and CHOP protein expression, but the effects on CHAC1 protein do not seem to be satisfactory as a mechanism for Notch inhibition. Perhaps something else is blocking Notch expression?

In the rebuttal, the two references provided by the authors do not alleviate concern that CHAC1 might not be acting as a Notch cleavage inhibitor in the T-ALL context. The Meng et al paper studied B-ALL not T-ALL and did not evaluate CHAC1 as a possible Notch cleavage inhibitor. Likewise, the Chang et al paper did not evaluate CHAC1 as a possible Notch cleavage inhibitor. Therefore, whether CHAC1 is a Notch cleavage inhibitor in the T-ALL context remains an open question. While the authors are correct that Supplementary Fig. S4G-I show that Extract #12 clearly induces CHAC1 protein expression, Main Fig. 3H shows that the extract combination 333-18A+CBVD+CBD, which is the focus of this manuscript, has unclear effects. If the extract combination has no effect on CHAC1 but has the same effects on Notch1 expression as the full extract, then there is reduced support for the authors' conclusion that the full extract and the 333-18A+CBVD+CBD combination inhibit Notch through CHAC1 induction.

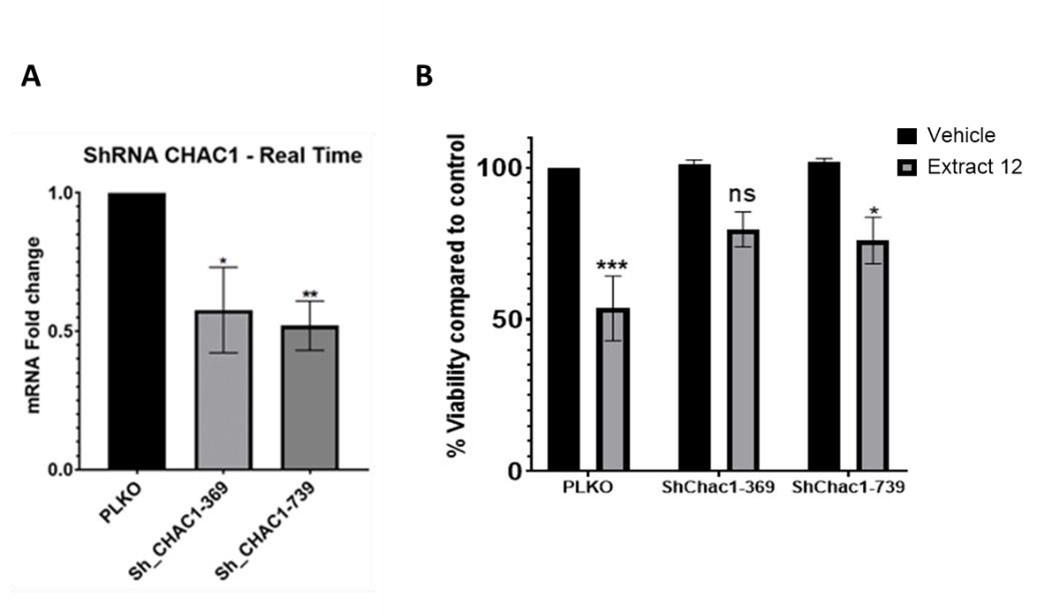

(6) The authors provide a new figure on page 5 of the rebuttal that was not requested. It is supposed to show that CHAC1 loss protects T-ALL cells from Extract #12-induced cell population decline. Unfortunately, this figure is not conclusive. The empty vector PLKO is not an appropriate negative control. The field uses non-targeting shRNA controls like pLKO-luciferase to control for induction of the RNA interference pathway. Further, the viability data in panel B is normalized such that the effect of shCHAC1 on viability is masked. Showing non-normalized data is important, because if shCHAC1 impairs viability compared to control shRNA, then CHAC1might have effects on non-Notch pathways, which would reinforce the above concern in Point #5 that CHAC1 might not act as a Notch inhibitor in the T-ALL context. Separately, if this experiment had tested whether CHAC1 knockdown increases Notch cleavage and Notch target gene expression like DTX1, HES1 and MYC, then such data would have helped address Point #5.

(7) Fig. 4B-C/S5D-E. These Western blots of NICD expression are consistent with the cannabinoid combination blocking Furin-mediated NOTCH1 cleavage, which is reversed by ISR inhibition. However, there are many mechanisms that regulate NICD expression. To support their conclusion that the effects are specifically Furin-medated, the authors should probe full length (uncleaved) NOTCH1 in their Western blots. While the authors showed that the full extract (#12) increased uncleaved NOTCH1 expression in their Cancer Communications paper, a major conclusion of the manuscript is that the cannabinoid combination 333-18A+CBVD+CBD reproduces the effect of the full extract (#12). To support this conclusion, the authors should probe key blots for full-length Notch to show that the cannabinoid combination increases uncleaved NOTCH1 just like Extract #12 did in the authors' Cancer Communications paper.

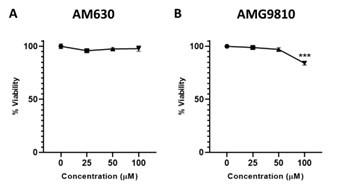

(8) Fig. S4A-B. While these pharmacologic data are suggestive that Extract #12 reduces NICD expression through the CB2 receptor and TRPV1 channel, the doses used are very high (50uM). To exclude off-target effects, these data should be paired with genetic data to support the authors' conclusions. In the rebuttal, the authors provide dose response cell viability curves of the CB2 and TRPV1 inhibitors. These curves do not exclude the possibility that 50uM has off-target effects. This reviewer notes that Reviewer #1 had similar concerns and that both reviewers requested genetic validation of the pharmacological data. These data were not provided in the revision.

(9) Since the authors have performed gene expression profiling, an orthogonal test to confirm that Extract #12 acts through the Notch pathway is to perform enrichment analysis using Notch target gene signatures in T-ALL (e.g. Wang PNAS 2013). In contrast to the authors' rebuttal, this reviewer does not see any enrichment analysis (e.g. GSEA plots) performed on the microarray data to show that Extract #12 inhibits the Notch pathway.

(10) The revised manuscript still retains references that microarray data are "RNA-seq" data, which is inaccurate (see page 10, line 160; Figure 3 legend; page 12, line 169; page 27, line 428; page 36, line 741)