Peer review process

Not revised: This Reviewed Preprint includes the authors’ original preprint (without revision), an eLife assessment, public reviews, and a provisional response from the authors.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorMing MengUniversity of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, United States of America

- Senior EditorTirin MooreStanford University, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Stanford, United States of America

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Strengths:

The authors introduced a new adapted paradigm from continuous flash suppression (CFS). The new CFS tracking paradigm (tCFS) allowed them to measure suppression depth in addition to breakthrough thresholds. This innovative approach provides a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying continuous flash suppression. The observed uniform suppression depth across target types (e.g., faces and gratings) is novel and has new implications for how the visual system works. The experimental manipulation of the target contrast change rate, as well as the modeling, provided strong support for an early interocular suppression mechanism. The authors argue that the breakthrough threshold alone is not sufficient to infer about unconscious processing.

Weaknesses:

A major finding in the current study is the null effect of the image categories on the suppression depth measured in the tCFS paradigm, from which the authors infer an early interocular mechanism underlying CFS suppression. This is not strictly logical as an inference based on the null effect. The authors may consider statistical evaluation of the null results, such as equivalence tests or Bayesian estimation.

More importantly, since limited types of image categories have been tested, there may be some exceptional cases. According to "Twofold advantages of face processing with or without visual awareness" by Zhou et al. (2021), pareidolia faces (face-like non-face objects) are likely to be an exceptional case. They measured bidirectional binocular rivalry in a blocked design, similar to the discrete condition used in the current study. They reported that the face-like non-face object could enter visual awareness in a similar fashion to genuine faces but remain in awareness in a similar fashion to common non-face objects. We could infer from their results that: when compared to genuine faces, the pareidolia faces would have a similar breakthrough threshold but a higher suppression threshold; when compared to common objects, the pareidolia faces would have a similar suppression threshold but a low breakthrough threshold. In this case, the difference between these two thresholds for pareidolia faces would be larger than either for genuine faces or common objects. Thus, it would be important for the authors to discuss the boundary between the findings and the inferences.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary

The paper introduces a valuable method, tCFS, for measuring suppression depth in continuous flash suppression (CFS) experiments. tCFS uses a continuous-trial design instead of the discrete trials standard in the literature, resulting in faster, better controlled, and lower-variance estimates. The authors measured suppression depth during CFS for the first time and found similar suppression depths for different image categories. This finding provides an interesting contrast to previous results that breakthrough thresholds differ for different image categories and refine inferences of subconscious processing based solely on breakthrough thresholds. However, the paper overreaches by claiming breakthrough thresholds are insufficient for drawing certain conclusions about subconscious processing.

Strengths

1. The tCFS method, by using a continuous-trial design, quickly estimates breakthrough and re-suppression thresholds. Continuous trials better control for slowly varying factors such as adaptation and attention. Indeed, tCFS produces estimates with lower across-subject variance than the standard discrete-trial method (Fig. 2). The tCFS method is straightforward to adopt in future research on CFS and binocular rivalry.

2. The CFS literature has lacked re-suppression threshold measurements. By measuring both breakthrough and re-suppression thresholds, this work calculated suppression depth (i.e., the difference between the two thresholds), which warrants different interpretations from the breakthrough threshold alone.

3. The work found that different image categories show similar suppression depths, suggesting some aspects of CFS are not category-specific. This result enriches previous findings that breakthrough thresholds vary with image categories. Re-suppression thresholds vary symmetrically, such that their differences are constant.

Weaknesses

1. The results and arguments in the paper do not support the claim that 'variations in breakthrough thresholds alone are insufficient for inferring unconscious or preferential processing of given image categories,' to take one example phrasing from the abstract. The same leap in reasoning recurs on lines 28, 39, 125, 566, 666, 686, 759, etc.

Take, for example, the arguments on lines 81-83. Grant that images are inequivalent, and this explains different breakthrough times. This is still no argument against differential subconscious processing. Why are images non-equivalent? Whatever the answer, does it qualify as 'residual processing outside of awareness'? Even detecting salience requires some processing. The authors appear to argue otherwise on lines 694-696, for example, by invoking the concept of effective contrasts, but why is effective contrast incompatible with partial processing? Again, does detecting (effective) contrast not involve some processing? The phrases 'residual processing outside of awareness' and 'unconscious processing' are broad enough to encompass bottom-up salience and effective contrast. Salience and (effective) contrast are arguably uninteresting, but that is a different discussion. The authors contrast 'image categories' or semantics with 'low-level factors.' In my opinion, this is a clearer contrast worth emphasizing more. However, semantic processing is not equal to subconscious processing writ large. The preceding does not detract from the interest in finding uniform suppression depth. Suppression depth and absolute bCFS can conceivably be due to orthogonal mechanisms warranting their own interpretations. In fact, the authors briefly take this position in the Discussion (lines 696-704, 'A hybrid model ...'). The involvement of different mechanisms would defeat the argument on lines 668-670.

2. These two hypotheses are confusing and should be more clearly distinguished: a) varying breakthrough times may be due to low-level factors (lines 76-79); b) uniform suppression depth may also arise from early visual mechanisms (e.g., lines 25-27).

Neutral remarks

The depth between bCFS and reCFS depended on measurement details such as contrast change speed and continuous vs. discrete trials. With discrete trials, the two thresholds showed inverse relations (i.e., reCFS > bCFS) in some participants. The authors discuss possible reasons at some length (adaptation, attention, etc. ). Still, a variable measure does not clearly indicate a uniform mechanism.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Summary:

In the 'bCFS' paradigm, a monocular target gradually increases in contrast until it breaks interocular suppression by a rich monocular suppressor in the other eye. The present authors extend the bCFS paradigm by allowing the target to reduce back down in contrast until it becomes suppressed again. The main variable of interest is the contrast difference between breaking suppression and (re) entering suppression. The authors find this difference to be constant across a range of target types, even ones that differ substantially in the contrast at which they break interocular suppression (the variable conventionally measured in bCFS). They also measure how the difference changes as a function of other manipulations. Interpretation in terms of the processing of unconscious visual content, as well as in terms of the mechanism of interocular suppression.

Strengths:

Interpretation of bCFS findings is mired in controversy, and this is an ingenuous effort to move beyond the paradigm's exclusive focus on breaking suppression. The notion of using the contrast difference between breaking and entering suppression as an index of suppression depth is interesting, but I also feel like it can be misleading at times, as detailed below.

Weaknesses:

Here's one doubt about the 'contrast difference' measure used by the authors. The authors seem confident that a simple subtraction is meaningful after the logarithmic transformation of contrast values, but doesn't this depend on exactly what shape the contrast-response function of the relevant neural process has? Does a logarithmic transformation linearize this function irrespective of, say, the level of processing or the aspect of processing that we're talking about? Given that stimuli differ in terms of the absolute levels at which they break (and re-enter) suppression, the linearity assumption needs to be well supported for the contrast difference measure to be comparable across stimuli.

Here's a more conceptual doubt. The authors introduce their work by discussing ambiguities in the interpretation of bCFS findings with regard to preferential processing, unconscious processing, etc. A large part of the manuscript doesn't really interpret the present 'suppression depth' findings in those terms, but at the start of the discussion section (lines 560-567) the authors do draw fairly strong conclusions along those lines: they seem to argue that the constant 'suppression depth' value observed across different stimuli argues against preferential processing of any of the stimuli, let alone under suppression. I'm not sure I understand this reasoning. Consider the scenario that the visual system does preferentially process, say, emotional face images, and that it does so under suppression as well as outside of suppression. In that scenario, one might expect the contrast at which such a face breaks suppression to be low (because the face is preferentially processed under suppression) and one might also expect the contrast at which the face enters suppression to be low (because the face is preferentially processed outside of suppression). So the difference between the two contrasts might not stand out: it might be the same as for a stimulus that is not preferentially processed at all. In sum, even though the author's label of 'suppression depth' on the contrast difference measure is reasonable from some perspectives, it also seems to be misleading when it comes to what the difference measure can actually tell us that bCFS cannot.

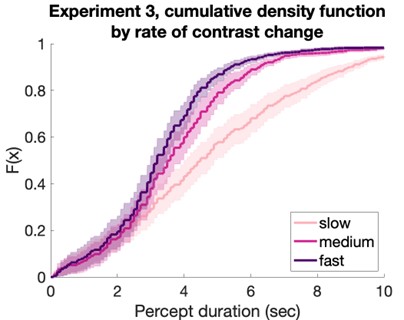

The authors acknowledge that non-zero reaction time inflates their 'suppression depth' measure, and acknowledge that this inflation is worse when contrast ramps more quickly. But they argue that these effects are too small to explain either the difference between breaking contrast and re-entering contrast to begin with, or the increase in this difference with the contrast ramping rate. I agree with the former: I have no doubt that stimuli break suppression (ramping up) at a higher contrast than the one at which they enter suppression (ramping down). But about the latter, I worry that the RT estimate of 200 ms may be on the low side. 200 ms may be reasonable for a prepared observer to give a speeded response to a clearly supra-threshold target, but that is not the type of task observers are performing here. One estimate of RT in a somewhat traditional perceptual bistability task is closer to 500 ms (Van Dam & Van Ee, Vis Res 45 2005), but I am uncertain what a good guess is here. Bottom line: can the effect of contrast ramping rate on 'suppression depth' be explained by RT if we use a longer but still reasonable estimated RT than 200 ms?

A second remark about the 'ramping rate' experiment: if we assume that perceptual switches occur with a certain non-zero probability per unit time (stochastically) at various contrasts along the ramp, then giving the percept more time to switch during the ramping process will lead to more switches happening at an earlier stage along the ramp. So: ramping contrast upward more slowly would lead to more switches at relatively low contrast, and ramping contrast downward more slowly would lead to more switches at relatively high contrasts. This assumption (that the probability of switching is non-zero at various contrasts along the ramp) seems entirely warranted. To what extent can that type of consideration explain the result of the 'ramping rate' experiment?

When tying the 'dampened harmonic oscillator' finding to dynamic systems, one potential concern is that the authors are seeing the dampened oscillating pattern when plotting a very specific thing: the amount of contrast change that happened between two consecutive perceptual switches, in a procedure where contrast change direction reversed after each switch. The pattern is not observed, for instance, in a plot of neural activity over time, threshold settings over time, etcetera. I find it hard to assess what the observation of this pattern when representing a rather unique aspect of the data in such a specific way, has to do with prior observations of such patterns in plots with completely different axes.