Author Response

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

eLife assessment

This valuable study introduces an innovative method for measuring interocular suppression depth, which implicates mechanisms underlying subconscious visual processing. The evidence supporting the effectiveness of this method would be solid after successfully addressing concerns raised by the reviewers. The novel method will be of interest not only to cognitive psychologists and neuroscientists who study sensation and perception but also to philosophers who work on theories of consciousness.

Thank you for the recognition and appreciation of our work.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Strengths:

The authors introduced a new adapted paradigm from continuous flash suppression (CFS). The new CFS tracking paradigm (tCFS) allowed them to measure suppression depth in addition to breakthrough thresholds. This innovative approach provides a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underlying continuous flash suppression. The observed uniform suppression depth across target types (e.g., faces and gratings) is novel and has new implications for how the visual system works. The experimental manipulation of the target contrast change rate, as well as the modeling, provided strong support for an early interocular suppression mechanism. The authors argue that the breakthrough threshold alone is not sufficient to infer about unconscious processing.

Weaknesses:

A major finding in the current study is the null effect of the image categories on the suppression depth measured in the tCFS paradigm, from which the authors infer an early interocular mechanism underlying CFS suppression. This is not strictly logical as an inference based on the null effect. The authors may consider statistical evaluation of the null results, such as equivalence tests or Bayesian estimation.

We have now included a Bayesian model comparison (implemented in JASP), to assess the strength of evidence in favour of the alternative hypothesis (or null effect). For example in Experiment 1 (comparing discrete to tCFS), we found inconsistent evidence in favour of the null effect of image-category on suppression depth:

Lines 382 – 388: “We quantified the evidence for this null-effect on suppression depth with a subsequent Bayesian model comparison. A Bayesian repeated-measures ANOVA (2 x 2; procedure x image type on suppression depth) found that the best model to explain suppression depth included the main effect of procedure (BF10 = 3231.74), and weak evidence/data insensitivity for image type (BF10 = 0.37). This indicates that the data was insensitive as to whether image-type was better at predicting suppression depth than the null model.”

In Experiment 2, which was specifically designed to investigate the effect of image category on suppression depth, we found strong evidence in favour of the null:

Lines 429 – 431: “A Bayesian repeated-measures ANOVA (1 x 5, effect of image categories on suppression depth), confirmed strong evidence in favour of the null hypothesis (BF01 =20.30).

In Experiment 3, we also had image categories, but the effect of rate of contrast change was our main focus. For completeness, we have also included the Bayes factors for image-category in Experiment 3 in our text.

Lines 487- 490> “This null-effect of image-type was again confirmed with a Bayesian model comparison (3 speed x 4 image categories on suppression depth), demonstrating moderate support for the null effect of image category (BF01= 4.06).”

We have updated our Methods accordingly with a description of this procedure

Lines 297-305: “We performed Bayesian model comparison to quantify evidence for and against the null in JASP, using Bayesian repeated measures ANOVAs (uninformed prior with equal weight to all models). We report Bayes factors (B) for main effects of interest (e.g. effect of image type on suppression depth), as evidence in favour compared to the null model (BF10= B). Following the guidelines recommended in (Dienes 2021), B values greater than 3 indicate moderate evidence for H1 over H0, and B values less than 1/3 indicate moderate evidence in favour of the null. B values residing between 1/3 and 3 are interpreted as weak evidence, or an insensitivity of the data to distinguish between the null and alternative models.”

More importantly, since limited types of image categories have been tested, there may be some exceptional cases. According to "Twofold advantages of face processing with or without visual awareness" by Zhou et al. (2021), pareidolia faces (face-like non-face objects) are likely to be an exceptional case. They measured bidirectional binocular rivalry in a blocked design, similar to the discrete condition used in the current study. They reported that the face-like non-face object could enter visual awareness in a similar fashion to genuine faces but remain in awareness in a similar fashion to common non-face objects. We could infer from their results that: when compared to genuine faces, the pareidolia faces would have a similar breakthrough threshold but a higher suppression threshold; when compared to common objects, the pareidolia faces would have a similar suppression threshold but a low breakthrough threshold. In this case, the difference between these two thresholds for pareidolia faces would be larger than either for genuine faces or common objects. Thus, it would be important for the authors to discuss the boundary between the findings and the inferences.

This is correct. We acknowledge that our sampling of image-categories is limited, and have added a treatment of this limitation in our discussion. We have expanded on the particular case of Zhou et al (2021), and the possibility of the asymmetries suggested:

Lines 669 – 691: “As a reminder, we explicitly tested image types that in other studies have shown differential susceptibility to CFS attributed to some form of expedited unconscious processing. Nevertheless, one could argue that our failure to obtain evidence for category specific suppression depth is based on the limited range of image categories sampled in this study. We agree it would be informative to broaden the range of image types tested using tCFS to include images varying in familiarity, congruence and affect. We can also foresee value in deploying tCFS to compare bCFS and reCFS thresholds for visual targets comprising physically meaningless ‘tokens’ whose global configurations can synthesise recognizable perceptual impressions. To give a few examples, dynamic configurations of small dots varying in location over time can create the compelling impression of rotational motion of a rigid, 3D object (structure from motion) or of a human engaged in given activity (biological motion) (Grossmann & Dobbins, 2006; Watson et al., 2004). These kinds of visual stimuli are associated with neural processing in higher-tier visual areas of the human brain, including the superior occipital lateral region (e.g., Vanduffel et al., 2002) and the posterior portion of the superior temporal sulcus (e.g., Grossman et al., 2000). These kinds of perceptually meaningful impressions of objects from rudimentary stimulus tokens are capable of engaging binocular rivalry. Such stimuli would be particularly useful in assessing high-level processing in CFS because they can be easily manipulated using phase-scrambling to remove the global percept without altering low-level stimulus properties. In a similar vein, small geometric shapes can be configured so as to resemble human or human-like faces, such as those used by (Zhou et al., 2021)[1]. These kinds of faux faces could be used in concert with tCFS to compare suppression depth with that associated with actual faces.

[1] Zhou et al. (2021) derived dominance and suppression durations with fixed-contrast images. In their study, genuine face images and faux faces remained suppressed for equivalent durations whereas genuine faces remained dominant significantly longer than did faux faces. The technique used by those investigators - interocular flash suppression (Wolfe, 1994) - is quite different from CFS in that it involves abrupt, asynchronous presentation of dissimilar stimuli to the two eyes. It would be informative to repeat their experiment using the tCFS procedure.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary

The paper introduces a valuable method, tCFS, for measuring suppression depth in continuous flash suppression (CFS) experiments. tCFS uses a continuous-trial design instead of the discrete trials standard in the literature, resulting in faster, better controlled, and lower-variance estimates. The authors measured suppression depth during CFS for the first time and found similar suppression depths for different image categories. This finding provides an interesting contrast to previous results that breakthrough thresholds differ for different image categories and refine inferences of subconscious processing based solely on breakthrough thresholds. However, the paper overreaches by claiming breakthrough thresholds are insufficient for drawing certain conclusions about subconscious processing.

We agree that breakthrough thresholds can provide useful information to draw conclusions about unconscious processing – as our procedure is predicated on breakthrough thresholds. Our key point is that breakthrough provides only half of the needed information.

We have amended our manuscript thoroughly (detailed below) to accommodate this nuance and avoid this overreaching claim.

Strengths

(1) The tCFS method, by using a continuous-trial design, quickly estimates breakthrough and re-suppression thresholds. Continuous trials better control for slowly varying factors such as adaptation and attention. Indeed, tCFS produces estimates with lower across-subject variance than the standard discrete-trial method (Fig. 2). The tCFS method is straightforward to adopt in future research on CFS and binocular rivalry.

(2) The CFS literature has lacked re-suppression threshold measurements. By measuring both breakthrough and re-suppression thresholds, this work calculated suppression depth (i.e., the difference between the two thresholds), which warrants different interpretations from the breakthrough threshold alone.

(3) The work found that different image categories show similar suppression depths, suggesting some aspects of CFS are not category-specific. This result enriches previous findings that breakthrough thresholds vary with image categories. Re-suppression thresholds vary symmetrically, such that their differences are constant.

Thank you for this positive and succinct summary of our contribution. We have adopted your 3rd point “... suggesting that some aspects...” in our revised manuscript to more appropriately treat the ways that bCFS and reCFS thresholds may interact with suppression depths. For example:

Lines 850 – 852: “These [low level] factors could be parametrically varied to examine specifically whether they modulate bCFS thresholds alone, or whether they also cause a change in suppression depth by asymmetrically affecting reCFS thresholds”.

Weaknesses

(1) The results and arguments in the paper do not support the claim that 'variations in breakthrough thresholds alone are insufficient for inferring unconscious or preferential processing of given image categories,' to take one example phrasing from the abstract. The same leap in reasoning recurs on lines 28, 39, 125, 566, 666, 686, 759, etc.

We have thoroughly updated our manuscript with respect to mentions of preferential processing, to avoid this leap in reasoning throughout. For example, this phrase in the abstract now reads:

Lines 27-30: “More fundamentally, it shows that variations in bCFS thresholds alone are insufficient for inferring whether the barrier to achieving awareness exerted by interocular suppression is weaker for some categories of visual stimuli compared to others”.

Take, for example, the arguments on lines 81-83. Grant that images are inequivalent, and this explains different breakthrough times. This is still no argument against differential subconscious processing. Why are images non-equivalent? Whatever the answer, does it qualify as 'residual processing outside of awareness'? Even detecting salience requires some processing. The authors appear to argue otherwise on lines 694-696, for example, by invoking the concept of effective contrasts, but why is effective contrast incompatible with partial processing? Again, does detecting (effective) contrast not involve some processing? The phrases 'residual processing outside of awareness' and 'unconscious processing' are broad enough to encompass bottom-up salience and effective contrast. Salience and (effective) contrast are arguably uninteresting, but that is a different discussion. The authors contrast 'image categories' or semantics with 'low-level factors.' In my opinion, this is a clearer contrast worth emphasizing more. However, semantic processing is not equal to subconscious processing writ large.

We are in agreement with your analysis that differential subconscious processing may contribute to differences between images, and have updated our manuscript to clarify this possibility. In particular, we have now included a section in our Discussion which offers a suggestion for future research, linking sensitivity to different low-level image features with differences in gain of the respective contrast-response functions.

From Lines 692 – 722: “Next we turn to another question raised about our conclusion concerning invariant depth of suppression: If certain image types have overall lower bCFS and reCFS contrast thresholds relative to other image types, does that imply that images in the former category enjoy “preferential processing” relative to those in the latter? Given the fixed suppression depth, what might determine the differences in bCFS and reCFS thresholds? Figure 3 shows that polar patterns tend to emerge from suppression at slightly lower contrasts than do gratings and that polar patterns, once dominant, tend to maintain dominance to lower contrasts than do gratings and this happens even though the rate of contrast change is identical for both types of stimuli. But while rate of contrast change is identical, the neural responses to those contrast changes may not be the same: neural responses to changing contrast will depend on the neural contrast response functions (CRFs) of the cells responding to each of those two types of stimuli, where the CRF defines the relationship between neural response and stimulus contrast. CRFs rise monotonically with contrast and typically exhibit a steeply rising initial response as stimulus contrast rises from low to moderate values, followed by a reduced growth rate for higher contrasts. CRFs can vary in how steeply they rise and at what contrast they achieve half-max response. CRFs for neurons in mid-level vision areas such as V4 and FFA (which respond well to polar stimuli and faces, respectively) are generally steeper and shifted towards lower contrasts than CRFs for neurons in primary visual cortex (which responds well to gratings). Therefore, the effective strength of the contrast changes in our tCFS procedure will depend on the shape and position of the underlying CRF, an idea we develop in more detail in Supplementary Appendix 1, comparing the case of V1 and V4 CRFs. Interestingly, the comparison of V1 and V4 CRFs shows two interesting points: (i) that V4 CRFs should produce much lower bCFS and reCFS thresholds than V1 CRFs, and (ii) that V4 CRFs should produce more suppression than V1 CRFs. Our data do not support either prediction: Figure 3 shows that bCFS and reCFS thresholds are very similar for all image categories and suppression depth is uniform. There is no room in these results to support the claim that certain images receive “preferential processing” or processing outside of awareness, although there are many other kinds of images still to be tested and exceptions may potentially be found. As a first step in exploring this idea, one could use standard psychophysical techniques (e.g., (Ling & Carrasco, 2006)) to derive CRFs for different categories of patterns and then measure suppression depth associated with those patterns using tCFS.”

We have also expanded on this nuanced line of reasoning in a new Supplementary Appendix for the interested reader.

The preceding does not detract from the interest in finding uniform suppression depth. Suppression depth and absolute bCFS can conceivably be due to orthogonal mechanisms warranting their own interpretations. In fact, the authors briefly take this position in the Discussion (lines 696-704, 'A hybrid model ...'). The involvement of different mechanisms would defeat the argument on lines 668-670.

We agree with this analysis, and note our response to Reviewer 1 and the possibility of exceptional cases that may affect absolute bCFS or reCFS thresholds independently.

Similarly, we agree with the notion that some aspects of CFS may not be category specific. The symmetric relationship of thresholds for a given category of stimuli should be assessed in the context of other categories, such as with pontillist images and by incorporating semantic features of images into the mask as in Che et al. (2019) and Han et al. (2021). This line of reasoning and suggestions for future research is provided in the revised discussion, beginning:

Lines 67: “Nevertheless, one could argue that our failure to obtain evidence for category specific suppression depth is based on a limited range of image categories….”

(2) These two hypotheses are confusing and should be more clearly distinguished: a) varying breakthrough times may be due to low-level factors (lines 76-79); b) uniform suppression depth may also arise from early visual mechanisms (e.g., lines 25-27).

Thank you for highlighting this opportunity for clarification. We have updated our text:

Lines 25 – 27: “This uniform suppression depth points to a single mechanism of CFS suppression, one that likely occurs early in visual processing, because suppression depth was not modulated by target salience or complexity”

Lines 78 – 79: “Sceptics argue, however, that differences in breakthrough times can be attributed to low-level factors such as spatial frequency, orientation and contrast that vary between images”

Neutral remarks

The depth between bCFS and reCFS depended on measurement details such as contrast change speed and continuous vs. discrete trials. With discrete trials, the two thresholds showed inverse relations (i.e., reCFS > bCFS) in some participants. The authors discuss possible reasons at some length (adaptation, attention, etc. ). Still, a variable measure does not clearly indicate a uniform mechanism.

We have ensured our revised manuscript makes no mention of a uniform mechanism, although we frequently mention our result of uniform suppression depth.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Summary:

In the 'bCFS' paradigm, a monocular target gradually increases in contrast until it breaks interocular suppression by a rich monocular suppressor in the other eye. The present authors extend the bCFS paradigm by allowing the target to reduce back down in contrast until it becomes suppressed again. The main variable of interest is the contrast difference between breaking suppression and (re) entering suppression. The authors find this difference to be constant across a range of target types, even ones that differ substantially in the contrast at which they break interocular suppression (the variable conventionally measured in bCFS). They also measure how the difference changes as a function of other manipulations. Interpretation in terms of the processing of unconscious visual content, as well as in terms of the mechanism of interocular suppression.

Thank you for your positive assessment of our methodology.

Strengths:

Interpretation of bCFS findings is mired in controversy, and this is an ingenuous effort to move beyond the paradigm's exclusive focus on breaking suppression. The notion of using the contrast difference between breaking and entering suppression as an index of suppression depth is interesting, but I also feel like it can be misleading at times, as detailed below.

Weaknesses:

Here's one doubt about the 'contrast difference' measure used by the authors. The authors seem confident that a simple subtraction is meaningful after the logarithmic transformation of contrast values, but doesn't this depend on exactly what shape the contrast-response function of the relevant neural process has? Does a logarithmic transformation linearize this function irrespective of, say, the level of processing or the aspect of processing that we're talking about?

Given that stimuli differ in terms of the absolute levels at which they break (and re-enter) suppression, the linearity assumption needs to be well supported for the contrast difference measure to be comparable across stimuli.

Our motivation to quantify suppression depth after log-transform to decibel scale was two-fold. First, we recognised that the traditional use of a linear contrast ramp in bCFS is at odds with the well-characterised profile of contrast discrimination thresholds which obey a power law (Legge, 1981) and the observations that neural contrast response functions show the same compressive non-linearity in many different cortical processing areas (e.g.: V1, V2, V3, V4, MT, MST, FST, TEO. See (Ekstrom et al., 2009)). Increasing contrast in linear steps could thus lead to a rapid saturation of the response function, which may account for the overshoot that has been reported in many canonical bCFS studies. For example, in (Jiang et al., 2007), target contrast reached 100% after 1 second, yet average suppression times for faces and inverted faces were 1.36 and 1.76 seconds respectively. As contrast response functions in visual neurons saturate at high contrast, the upper levels of a linear contrast ramp have less and less effect on the target's strength. This approach to response asymptote may have exaggerated small differences between stimulus conditions and may have inflated some previously reported differences. In sum, the use of a log-transformed contrast ramp allows finer increments in contrast to be explored before saturation, a simple manipulation which we hope will be adopted by our field.

Second, by quantifying suppression depth as a decibel change we enable the comparison of suppression depth between experiments and laboratories, which inevitably differ in presentation environments. As a comparison, a reaction-time for bCFS of 1.36 s can not easily be compared without access to near-identical stimulation and testing environments. In addition once ramp contrast is log transformed it effectively linearises the neural contrast response function. This means that comparing different studies that use different contrast levels for masker or target can be directly compared because a given suppression depth (for example, 15 dB) is the same proportionate difference between bCFS and reCFS regardless of the contrasts used in the particular study.

We also acknowledge that different stimulus categories may engage neural and visual processing associated with different contrast gain values (e.g., magno- vs parvo-mediated processing). But the breaks and returns to suppression of a given stimulus category would be dependent on the same contrast gain function appropriate for that stimulus which thus permits their direct comparison. Indeed, this is why our novel approach offers a promising technique for comparing suppression depth associated with various stimulus categories (a point mentioned above). Viewed in this way, differences in actual durations of break times (such as we report in our paper) may tell us more about differences in gain control within neural mechanisms responsible for processing of those categories.

We have now included a summary of these arguments in a new paragraph of our discussion (from lines 696- cf Reviewer 2 above), as well as a new Supplementary Appendix.

Here's a more conceptual doubt. The authors introduce their work by discussing ambiguities in the interpretation of bCFS findings with regard to preferential processing, unconscious processing, etc. A large part of the manuscript doesn't really interpret the present 'suppression depth' findings in those terms, but at the start of the discussion section (lines 560-567) the authors do draw fairly strong conclusions along those lines: they seem to argue that the constant 'suppression depth' value observed across different stimuli argues against preferential processing of any of the stimuli, let alone under suppression. I'm not sure I understand this reasoning. Consider the scenario that the visual system does preferentially process, say, emotional face images, and that it does so under suppression as well as outside of suppression. In that scenario, one might expect the contrast at which such a face breaks suppression to be low (because the face is preferentially processed under suppression) and one might also expect the contrast at which the face enters suppression to be low (because the face is preferentially processed outside of suppression). So the difference between the two contrasts might not stand out: it might be the same as for a stimulus that is not preferentially processed at all. In sum, even though the author's label of 'suppression depth' on the contrast difference measure is reasonable from some perspectives, it also seems to be misleading when it comes to what the difference measure can actually tell us that bCFS cannot.

We have addressed this point with respect to the differences between suppression depth and overall value of contrast thresholds in our revised discussion (reproduced above), and supplementary appendix.

The authors acknowledge that non-zero reaction time inflates their 'suppression depth' measure, and acknowledge that this inflation is worse when contrast ramps more quickly. But they argue that these effects are too small to explain either the difference between breaking contrast and re-entering contrast to begin with, or the increase in this difference with the contrast ramping rate. I agree with the former: I have no doubt that stimuli break suppression (ramping up) at a higher contrast than the one at which they enter suppression (ramping down). But about the latter, I worry that the RT estimate of 200 ms may be on the low side. 200 ms may be reasonable for a prepared observer to give a speeded response to a clearly supra-threshold target, but that is not the type of task observers are performing here. One estimate of RT in a somewhat traditional perceptual bistability task is closer to 500 ms (Van Dam & Van Ee, Vis Res 45 2005), but I am uncertain what a good guess is here. Bottom line: can the effect of contrast ramping rate on 'suppression depth' be explained by RT if we use a longer but still reasonable estimated RT than 200 ms?

A 500 ms reaction time estimate would not account for the magnitude of the changes observed in Experiment 3. Suppression depths in our slow, medium, and fast contrast ramps were 9.64 dB, 14.64 dB and 18.97 dB, respectively (produced by step sizes of .035, .07 and .105 dB per video frame at 60 fps). At each rate, assuming a 500 ms reaction time for both thresholds would capture a change of 2.1 dB, 4.2 dB, 6.3 dB. This difference cannot account for the size of the effects observed between our different ramp speeds. Note that any critique using the RT argument also applies to all other bCFS studies which inevitably will have inflated breakthrough points for the same reason.

We’ve updated our discussion with this more conservative estimate:

Lines 744 – 747: “For example, if we assume an average reaction time of 500 ms for appearance and disappearance events, then suppression depth will be inflated by ~4.2 dB at the rate of contrast change used in Experiments 1 and 2 (.07 dB per frame at 60 fps). This cannot account for suppression depth in its entirety, which was many times larger at approximately 14 dB across image categories.”

Lines 755 – 760: [In Experiment 3] “Using the same assumptions of a 500 ms response time delay, this would predict a suppression depth of 2.1 dB, 4.2 dB and 6.3 dB for the slow, medium and fast ramp speeds respectively. However, this difference cannot account for the size of the effects (Slow 9.64 dB, Medium 14.6 dB, Fast 18.97 dB). The difference in suppression depth based on reaction-time delays (± 2.1 dB) also does not match with our empirical data (Medium - Slow = 4.96 dB; Fast - Medium = 4.37 dB)”

A second remark about the 'ramping rate' experiment: if we assume that perceptual switches occur with a certain non-zero probability per unit time (stochastically) at various contrasts along the ramp, then giving the percept more time to switch during the ramping process will lead to more switches happening at an earlier stage along the ramp. So: ramping contrast upward more slowly would lead to more switches at relatively low contrast, and ramping contrast downward more slowly would lead to more switches at relatively high contrasts. This assumption (that the probability of switching is non-zero at various contrasts along the ramp) seems entirely warranted. To what extent can that type of consideration explain the result of the 'ramping rate' experiment?

We agree that for a given ramp speed there is a variable probability of a switch in perceptual state for both bCFS and reCFS portions of the trial. To put it in other words, for a given ramp speed and a given observer the distribution of durations at which transitions occur will exhibit variance. We see that variance in our data (just as it’s present in conventional binocular rivalry duration histograms), as a non-zero probability of switches at very short durations (for example). One might surmise that slower ramp speeds would afford more opportunity for stochastic transitions to occur and that the measured suppression depths for slow ramps are underestimates of the suppression depth produced by contrast adaptation. Yet by the same token, the same underestimation would occur during fast ramp speeds, indicating that that difference may be even larger than we reported. In our revision we will spell this out in more detail, and indicate that a non-zero probability of switches at any time may lead to an underestimation of all recorded suppression depths.

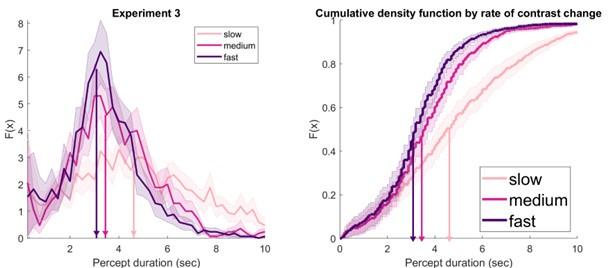

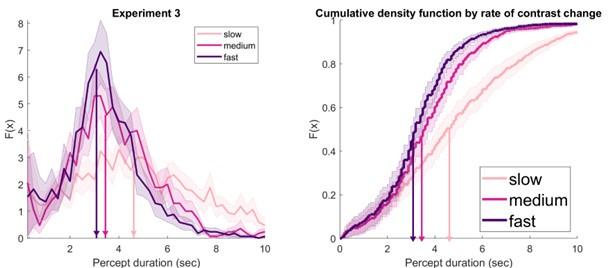

In our data, we believe the contribution of these stochastic switches are minimal. Our current Supplementary Figure 1(d) indicates that there is a non-zero probability of responses early in each ramp (e.g. durations < 2 seconds), yet these are a small proportion of all percept durations. This small proportion is clear in the empirical cumulative density function of percept durations, which we include below. Notably, during slow-ramp conditions, average percept durations actually increased, implying a resistance to any effect of early stochastic switching.

Author response image 1.

The data from Supplementary FIgure 1D. (right) Same data reproduced as a cumulative density function. The non-zero probability of a switch occurring (for example at very short percept durations) is clear, but a small proportion of all switches. Notably, In slow ramp trials, there is more time for this stochastic switching to occur, which should underestimate the overall suppression depth. Yet during slow-ramp conditions, average percept durations increased (vertical arrows), implying a resistance to any effect of early stochastic switching.

When tying the 'dampened harmonic oscillator' finding to dynamic systems, one potential concern is that the authors are seeing the dampened oscillating pattern when plotting a very specific thing: the amount of contrast change that happened between two consecutive perceptual switches, in a procedure where contrast change direction reversed after each switch. The pattern is not observed, for instance, in a plot of neural activity over time, threshold settings over time, etcetera. I find it hard to assess what the observation of this pattern when representing a rather unique aspect of the data in such a specific way, has to do with prior observations of such patterns in plots with completely different axes.

We acknowledge that fitting the DHO model to response order (rather than time) is a departure from previous investigations modelling oscillations over time. Our alignment to response order was a necessary step to avoid the smearing which occurs due to variation in individual participant threshold durations.

Our Supplementary Figure 1 shows the variation in participant durations for the three rates of contrast change. From this pattern we can expect that fitting the DHO to perceptual changes over time would result in the poorest fit for slow rates of change (with the largest variation in durations), and best fit for fast rates of change (with least variation in durations).

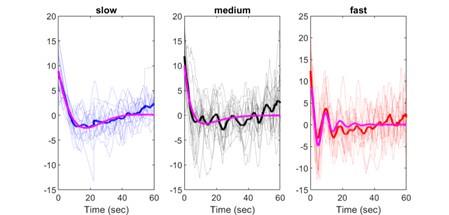

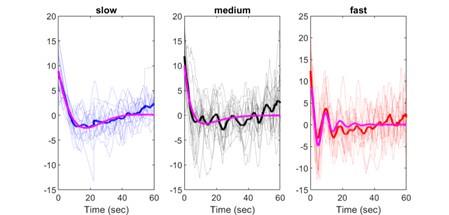

That is indeed what we see, reproduced in the review figure below. We include this to show the DHO is still applicable to perceptual changes over time when perceptual durations have relatively low variance (in the fast example), but not the alternate cases. Thus the DHO is not only produced by our alignment to response number - but this step is crucial to avoid the confound of temporal smearing when comparing between conditions.

Author response image 2.

DHO fit to perceptual thresholds over time. As a comparison to manuscript Figure 5 (aligning to response order), here we display the raw detrended changes in threshold over time per participant, and their average. Individual traces are shown in thin lines, the average is thick. Notably, in the slow and medium conditions, when perceptual durations had relatively high variance, the DHO is a poor fit to the average (shown in pink). The DHO is still an excellent fit in fast conditions, when modelling changes in threshold over time, owing to the reduced variance in perceptual durations (cf. Supplementary Figure 1). As a consequence, to remove the confound of individual participant durations, we have fitted the DHO when aligned to response order in our manuscript.

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations For The Authors):

The terminology used: "suppression depth". The depth of interocular suppression indexed by detection threshold has long been used in the literature, such as in Tsuchiya et al., 2006.

I notice that this manuscript has created a totally different manipulative definition of the depth of suppression, the authors should make this point clear to the readers to avoid confusion.

We believe that our procedure does not create a new definition for suppression depth, but rather utilises the standard definition used for many years in the binocular rivalry literature: the ratio between a threshold measured for a target while it is in the state of suppression and for that same target when in the dominance state.

We have now revised our introduction to make the explicit continuation from past methods to our present methodology clear:

Lines 94 – 105: “One method for measuring interocular suppression is to compare the threshold for change-detection in a target when it is monocularly suppressed and when it is dominant, an established strategy in binocular rivalry research (Alais, 2012; Alais et al., 2010; Alais & Melcher, 2007; Nguyen et al., 2003). Probe studies using contrast as the dependent variable for thresholds measured during dominance and during suppression can advantageously standardise suppression depth in units of contrast within the same stimulus (e.g., Alais & Melcher, 2007; Ling et al., 2010). Ideally, the change should be a temporally smoothed contrast increment to the rival image being measured (Alais, 2012), a tactic that preludes abrupt onset transients and, moreover, provides a natural complement to the linear contrast ramps that are standard in bCFS research. In this study, we measure bCFS thresholds as the analogue of change-detection during suppression, and as their complement, record thresholds for returns to suppression (reCFS).”

The paper provides a new method to measure CFS bidirectionally. Given the possible exceptional case of pareidolia faces, it would be important to discuss how the bidirectional measurement offers more information, e.g., how the bottom-up and top-down factors would be involved in the breakthrough phase and the re-suppression phase.

In our discussion, we have now included the possibility of exceptional cases (such as pareidolia faces), and how an asymmetry may arise with respect to separate image categories affecting either bCFS or reCFS thresholds orthogonally.

Lines 688 - 691: “...In a similar vein, small geometric shapes can be configured so as to resemble human faces, such as those used by Zhou et al. (2021)[footnote]. These kinds of faux faces could be used in concert with tCFS to compare suppression depth with that associated with actual faces.

[footnote] Zhou et al. (2021) derived dominance and suppression durations with fixed-contrast images. In their study, genuine face images and faux faces remained suppressed for equivalent durations whereas genuine faces remained dominant significantly longer than did faux faces. The technique used by those investigators - interocular flash suppression (Wolfe, 1994) - is quite different from CFS in that it involves abrupt, asynchronous presentation of dissimilar stimuli to the two eyes. It would be informative to repeat their experiment using the tCFS procedure.”

What makes the individual results in the discrete condition much less consistent than the tCFS (in Figure 2c)? The authors discussed that motivation or attention to the task would change between bCFS and reCFS blocks (Line 589). But this point is not clear. Does not the attention to task also fluctuate in the tCFS paradigm, as the target continuously comes and goes?

We believe the discrete conditions have greater variance owing to the blocked design of the discrete conditions. A sequence of bCFS thresholds was collected in order (over ~15 mins), before switching to a sequence of back-to-back discrete reCFS thresholds (another ~15 mins), or a sequence of the tCFS condition. As the order of these blocks was randomized, thresholds collected in the discrete bCFS vs reCFS blocks could be separated by many minutes. In contrast, during tCFS, every bCFS threshold used to calculate the average is accompanied by a corresponding reCFS threshold collected within the same trial, separated by seconds. Thus the tCFS procedure naturally controls for waxing and waning attention, as within every change in attention, both thresholds are recorded for comparison.

A second advantage is that because the tCFS design changes contrast based on visibility, targets spend more time close to the threshold governing awareness. This reduced distance to thresholds remove the opportunity for other influences (such as oculomotor influences, blinks, etc), from introducing variance into the collected thresholds.

Experiment 3 reported greater suppression depth with faster contrast change. Because the participant's response was always delayed (e.g., they report after they become aware that the target has disappeared), is it possible that the measured breakthrough threshold gets lower, the re-suppression threshold gets higher, just because the measuring contrast is changing faster?

We have included an extended discussion of the contribution of reaction-times to the differences in suppression depth we report. Importantly, even a conservative reaction time of 500 ms, for both bCFS and reCFS events, cannot account for the difference in suppression depth between conditions.

Lines 755 – 760> “Using the same assumptions of a 500 ms response time delay, this would predict a suppression depth of 2.1 dB, 4.2 dB and 6.3 dB for the slow, medium and fast ramp speeds respectively. However, this difference cannot account for the size of the effects (Slow 9.64 dB, Medium 14.6 dB, Fast 18.97 dB). The difference in suppression depth based on reaction-time delays (± 2.1 dB) also does not match with our empirical data (Medium - Slow = 4.96 dB; Fast - Medium = 4.37 dB).”

In the current manuscript, some symbols are not shown properly (lines 145, 148, 150, 303).

Thank you for pointing this out, we will arrange with the editors to fix the typos.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations For The Authors):

Line 13: 'time needed'-> contrast needed?

This sentence was referring to previous experiments which predominantly focus on the time of breakthrough.

Line 57: Only this sentence uses saliency; everywhere else in the paper uses salience.

We have updated to salience throughout.

Fig. 1c: The higher variance in discrete measurement results may be due to more variation in discrete trials, e.g., trial duration and inter-trial intervals (ITIs). Tighter control is indeed one advantage of the continuous tCFS design. For the discrete condition, it would help to report more information about variation across trials. How long and variable are the trials? The ITIs? This information is also relevant to the hypothesis about adaptation in Experiment 3.

In the discrete condition, each trial ended after the collection of a single response. Thus the variability of the trials is the same as the variability of the contrast thresholds reported in Figure 2. The distribution of these ‘trials’ (aka percept durations), is also shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

The ITI between discrete trials was self-paced, and not recorded during the experiment.

Line 598: 'equivalently' is a strong word. The benefit is perhaps best stated relatively: bCFS and reCFS are measured under closer conditions (e.g., adaptation, attention) with continuous experiments compared to discrete ones.

We agree - and have amended our manuscript:

Lines 629 – 632: “Alternating between bCFS/reCFS tasks also means that any adaptation occurring over the trial will occur in close proximity to each threshold, as will any waning of attention. The benefit being that bCFS and reCFS thresholds are measured under closer conditions in continuous trials, compared to discrete ones.”

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations For The Authors):

Figure 1 includes fairly elaborate hypothetical results and how they would be interpreted by the authors, but I didn't really see any mention of this content in the main text. It wasn't until I started reading the caption that I figured it out. A more elaborate reference to the figure would prevent readers from overlooking (part of) the figure's message.

We have now made it clearer in the text that those details are contained in the caption to Figure 1.

Lines 113 – 115: “Figure 1 outlines hypothetical results that can be obtained when recording reCFS thresholds as a complement to bCFS thresholds in order to measure suppression depth.”

A piece of text seems to have been accidentally removed on line 267.

Thank you, this has now been amended