Peer review process

Revised: This Reviewed Preprint has been revised by the authors in response to the previous round of peer review; the eLife assessment and the public reviews have been updated where necessary by the editors and peer reviewers.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorJosé Biurrun ManresaNational Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET), National University of Entre Ríos (UNER), Oro Verde, Argentina

- Senior EditorTimothy BehrensUniversity of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

In this study, Millard and colleagues investigated if the analgesic effect of nicotine on pain sensitivity, assessed with two pain models, is mediated by Peak Alpha Frequency (PAF) recorded with resting state EEG. The authors found indeed that nicotine (4 mg, gum) reduced pain ratings during phasic heat pain but not cuff pressor algometry compared to placebo conditions. Nicotine also increased PAF (globally). However, mediation analysis revealed that the reduction in pain ratings elicited by the phasic heat pain after taking nicotine was not mediated by the changes in PAF. Also, the authors only partially replicated the correlation between PAF and pain sensitivity at baseline (before nicotine treatment). At the group-level no correlation was found, but an exploratory analysis showed that the negative correlation (lower PAF, higher pain sensitivity) was present in males but not in females. The authors discuss the lack of correlation.

In general, the study is rigorous, methodology is sound and the paper is well written. Results are compelling and sufficiently discussed.

Strengths:

Strengths of this study are the pre-registration, proper sample size calculation and data analysis. But also the presence of the analgesic effect of nicotine and the change in PAF.

Weaknesses:

It would even be more convincing if they had manipulated PAF directly.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The study by Millard et al. investigates the effect of nicotine on alpha peak frequency and pain in a very elaborate experimental design. According to the statistical analysis, the authors found a factor-corrected significant effect for prolonged heat pain but not for alpha peak frequency in response to the nicotine treatment.

Strengths:

I very much like the study design and that the authors followed their research line by aiming to provide a complete picture of the pain-related cortical impact of alpha peak frequency. This is very important work, even in the absence of any statistical significance. I also appreciate the preregistration of the study and the well-written and balanced introduction.

Weaknesses:

The weakness of the study revolves around two aspects:

(1) Source separation (ICA or similar) would have been more appropriate than electrode ROIs to extract the alpha signal. By using a source separation approach, different sources of alpha (mu, occipital alpha, laterality) could be disentangled.

(2) There is also a suggestion in the literature in the manuscript) that nicotine treatment may not work as intended. Instead, the authors' decision to use nicotine to modulate peak alpha frequency and pain was based on other, inappropriate work on chronic pain and chronic smokers. In the present study, the authors use nicotine treatment and transient painful stimulation in nonsmokers. The unfortunate decision to use nicotine severely hampered the authors' goal of the study.

Impact: The impact of the study could be to show what did not work to answer the authors' research questions. The study would have more impact with a more appropriate pain intervention model and an analysis strategy that untangles the different alpha sources.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

In this manuscript, Millard et al. investigate the effects of nicotine on pain sensitivity and peak alpha frequency (PAF) in resting state EEG. To this end, they ran a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled experiment involving 62 healthy adults that received either 4 mg nicotine gum (n=29) or placebo (n=33). Prolonged heat and pressure were used as pain models. Resting state EEG and pain intensity (assessed with a visual analog scale) were measured before and after the intervention. Additionally, several covariates (sex at birth, depression and anxiety symptoms, stress, sleep quality, among others) were recorded. Data was analyzed using ANCOVA-equivalent two-wave latent change score models, as well as repeated measures analysis of variance. Results do not show experimentally relevant changes of PAF or pain intensity scores for neither of the prolonged pain models due to nicotine intake.

The main strengths of the manuscript are its solid conceptual framework and the thorough experimental design. The researchers make a good case in the introduction and discussion for the need to further investigate the association of PAF and pain sensitivity. Furthermore, they proceed to carefully describe every aspect of the experiment in great detail, which is excellent for reproducibility purposes. Finally, they analyze the data from different and provide an extensive report of their results.

There are relevant weaknesses to highlight. Firstly, authors preregistered the study and the analysis plan, but the preregistration does not contain an estimation of the expected effect sizes or the rationale for the selected the sample size. Furthermore, the authors interpret their results in a way that is not supported by the evidence (which is notorious in the abstract and the first paragraph of the discussion). Even though some of the differences are statistically significant (e.g., global PAF, pain intensity ratings during heat pain), these differences are far from being experimentally or clinically relevant. The effect sizes observed are not sufficiently large to consider that pain sensitivity was modulated by the nicotine intake, which puts into question all the answers to the research questions posed in the study. The authors attempt to nuance this throughout the discussion, but in a way that is not compatible with the main claims.

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Summary:

In this study, Millard and colleagues investigated if the analgesic effect of nicotine on pain sensitivity, assessed with two pain models, is mediated by Peak Alpha Frequency (PAF) recorded with resting state EEG. The authors found indeed that nicotine (4 mg, gum) reduced pain ratings during phasic heat pain but not cuff pressor algometry compared to placebo conditions. Nicotine also increased PAF (globally). However, mediation analysis revealed that the reduction in pain ratings elicited by the phasic heat pain after taking nicotine was not mediated by the changes in PAF. Also, the authors only partially replicated the correlation between PAF and pain sensitivity at baseline (before nicotine treatment). At the group-level no correlation was found, but an exploratory analysis showed that the negative correlation (lower PAF, higher pain sensitivity) was present in males but not in females. The authors discuss the lack of correlation.

In general, the study is rigorous, methodology is sound and the paper is well-written. Results are compelling and sufficiently discussed.

Strengths:

Strengths of this study are the pre-registration, proper sample size calculation, and data analysis. But also the presence of the analgesic effect of nicotine and the change in PAF.

Weaknesses:

It would even be more convincing if they had manipulated PAF directly.

We thank Reviewer #1 for their positive and constructive comments regarding our study. We appreciate the view that the study was rigorous and methodologically sound, that the paper was well-written, and that the strengths included our pre-registration, sample size calculation, and data analysis.

In response to the reviewer's comment about more directly manipulating Peak Alpha Frequency (PAF), we agree that such an approach could provide a more direct investigation of the role of PAF in pain processing. We chose nicotine to modulate PAF as the literature suggested it was associated with a reliable increase in PAF speed. As mentioned in our Discussion, there are several alternative methods to manipulate PAF, such as non-invasive brain stimulation techniques (NIBS) like transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) or neurofeedback training. These approaches could help clarify whether a causal relationship exists between PAF and pain sensitivity. Although methods such as NIBS still require further investigation as there is little evidence for these approaches changing PAF (Millard et al., 2024).

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary:

The study by Millard et al. investigates the effect of nicotine on alpha peak frequency and pain in a very elaborate experimental design. According to the statistical analysis, the authors found a factor-corrected significant effect for prolonged heat pain but not for alpha peak frequency in response to the nicotine treatment.

Strengths:

I very much like the study design and that the authors followed their research line by aiming to provide a complete picture of the pain-related cortical impact of alpha peak frequency. This is very important work, even in the absence of any statistical significance. I also appreciate the preregistration of the study and the well-written and balanced introduction. However, it is important to give access to the preregistration beforehand.

Weaknesses:

The weakness of the study revolves around three aspects:

(1) I am not entirely convinced that the authors' analysis strategy provides a sufficient signal-tonoise ratio to estimate the peak alpha frequency in each participant reliably. A source separation (ICA or similar) would have been better suited than electrode ROIs to extract the alpha signal. By using a source separation approach, different sources of alpha (mu, occipital alpha, laterality) could be disentangled.

(2) Also, there's a hint in the literature (reference 49 in the manuscript) that the nicotine treatment may not work as intended. Instead, the authors' decision to use nicotine to modulate the peak alpha frequency and pain relied on other, not suitable work on chronic pain and permanent smokers. In the present study, the authors use nicotine treatment and transient painful stimulation on nonsmokers.

(3) In my view, the discussion could be more critical for some aspects and the authors speculate towards directions their findings can not provide any evidence. Speculations are indeed very important to generate new ideas but should be restricted to the context of the study (experimental pain, acute interventions). The unfortunate decision to use nicotine severely hampered the authors' aim of the study.

Impact:

The impact of the study could be to show what has not worked to answer the research questions of the authors. The authors claim that their approach could be used to define a biomarker of pain. This is highly desirable but requires refined methods and, in order to make the tool really applicable, more accurate approaches at subject level.

We thank reviewer #2 for their recognition of the study’s design, the importance of this research area, and the pre-registration of our study. In response to the weaknesses highlighted:

(1) We appreciate the reviewer’s suggestion to improve the signal-to-noise ratio by applying source separation techniques, such as ICA, which have now been performed and incorporated into the manuscript. Our original decision to use sensor-level ROIs followed the precedent set in previous studies, our rationale being to improve reproducibility and avoid biases from picking individual electrodes or manually picking sources. We have added analyses using an automated pipeline that selects components based on the presence of a peak in the alpha range and alignment with a predefined template topography representing sensorimotor sites. Here again we found no significant differences in the mediation results that used a sensor space sensorimotor ROI, further supporting the robustness of the chosen approach. ICA could still potentially disentangle different sources of alpha, such as occipital alpha and mu rhythm, and provide new insights into the PAF-pain relationship. We have now added a discussion in the manuscript about the potential advantages of source separation techniques and suggest that the possible contributions of separate alpha sources be investigated and compared to sensor space PAF as a direction for future research.

(2) We recognise the reviewer's concern regarding our choice of nicotine as a modulator of pain and alpha peak frequency (PAF). The meta-analysis by Ditre et al. (2016) indeed points to small effect sizes for nicotine's impact on experimental pain and highlights the potential for publication bias. However, our decision to use nicotine in this study was not primarily based on its direct analgesic effects, but rather on its well-documented ability to modulate PAF, in smoking and non-smoker populations, as outlined in our study aims.

In this regard, the intentional use of nicotine was to assess whether changes in PAF could mediate alterations in pain. This approach aligns with the broader concept that a direct effect of an intervention is not necessary to observe indirect effects (Fairchild & McDaniel, 2017). We have, however, revised our introduction to further clarify this rationale, highlighting that nicotine was used as a tool for PAF modulation, not solely for its potential analgesic properties.

(3) We agree with the reviewer’s observation that certain aspects of the Discussion could be more cautious, particularly regarding speculations about nicotine’s effects and PAF as a biomarker of pain. We have revised the Discussion to ensure that our interpretations are better grounded in the data from this study, clearly stating the limitations and avoiding overgeneralization. This revision focuses on a more critical evaluation of the potential relationships between PAF, nicotine, and pain sensitivity based solely on our experimental context.

Finally, We also apologize for not providing access to the preregistration earlier. This was an oversight on our end, and we will ensure that future preregistrations are made available upfront.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In this manuscript, Millard et al. investigate the effects of nicotine on pain sensitivity and peak alpha frequency (PAF) in resting state EEG. To this end, they ran a pre-registered, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled experiment involving 62 healthy adults who received either 4 mg nicotine gum (n=29) or placebo (n=33). Prolonged heat and pressure were used as pain models. Resting state EEG and pain intensity (assessed with a visual analog scale) were measured before and after the intervention. Additionally, several covariates (sex at birth, depression and anxiety symptoms, stress, sleep quality, among others) were recorded. Data was analyzed using ANCOVAequivalent two-wave latent change score models, as well as repeated measures analysis of variance. Results do not show *experimentally relevant* changes of PAF or pain intensity scores for either of the prolonged pain models due to nicotine intake.

The main strengths of the manuscript are its solid conceptual framework and the thorough experimental design. The researchers make a good case in the introduction and discussion for the need to further investigate the association of PAF and pain sensitivity. Furthermore, they proceed to carefully describe every aspect of the experiment in great detail, which is excellent for reproducibility purposes. Finally, they analyse the data from almost every possible angle and provide an extensive report of their results.

The main weakness of the manuscript is the interpretation of these results. Even though some of the differences are statistically significant (e.g., global PAF, pain intensity ratings during heat pain), these differences are far from being experimentally or clinically relevant. The effect sizes observed are not sufficiently large to consider that pain sensitivity was modulated by the nicotine intake, which puts into question all the answers to the research questions posed in the study.

We would like to express our gratitude to Reviewer #3 for their thoughtful and constructive review, including the positive feedback on the strengths of our study's conceptual framework, experimental design, and thorough methodological descriptions.

We acknowledge the concern regarding the experimental and clinical relevance of some statistically significant results (e.g., global PAF and pain intensity during heat pain) and agree that small effect sizes may limit their practical implications. However, our primary goal was to assess whether nicotine-induced changes in PAF mediate pain changes, rather than to demonstrate large direct effects on pain sensitivity. Nicotine was chosen for its known ability to modulate PAF, and our focus was on the mechanistic role of PAF in pain perception. To clarify this, we have revised the discussion to better differentiate between statistical significance, experimental relevance, and clinical applicability. We emphasize that this study represents a preliminary step towards understanding PAF’s mechanistic role in pain, rather than a direct clinical application.

We appreciate the suggestion to refine our interpretation. We have adjusted our language to ensure it aligns with the effect sizes observed and made recommendations for future research, such as testing different nicotine doses, to potentially uncover stronger or more clinically relevant effects.

Although modest, we believe these findings offer valuable insights into the potential mechanisms by which nicotine affects alpha oscillations and pain. We have also discussed how these small effects could become more pronounced in different populations (e.g., chronic pain patients) and over time, offering guidance for future research on PAF modulation and pain sensitivity.

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations For The Authors):

I have a number of points that the authors may want to consider for this or future work.

(1) By reviewing the literature provided by the authors in the introduction I think that using nicotine as a means to modulate pain and alpha peak frequency was a mistake. The only work that may give a hint on whether nicotine can modulate experimental pain is the meta-analysis by Ditre and colleagues (2016). They suggest that their small effect may contain a publication bias. I think the other "large body of evidence" is testing something else than analgesia.

Thank you for your consideration of our choice of nicotine in the study. The meta-analysis by Ditre and colleagues (2016) suggests small effect sizes for nicotine's impact on experimental pain, compared to the moderate effects claimed in some papers, especially when accounting for the potential publication bias you mentioned. However, our selection of nicotine was primarily driven by its documented ability to modulate PAF rather than its direct analgesic effects, as clearly stated in our aims. Therefore, we do not view our decision to use nicotine as a mistake; instead, it was aligned with our goal of assessing whether changes in PAF mediate alterations in pain and thus served as a valuable tool. This perspective aligns with the broader concept that a direct effect is not a prerequisite for observing indirect effects of an intervention on an outcome (Fairchild &

McDaniel, 2017). To further enhance clarity, we've revised the introduction to emphasize the role of nicotine in manipulating PAF in relation to our study's aims.

Previously we wrote: “A large body of evidence suggests that nicotine is an ideal choice for manipulating PAF, as both nicotine and smoking increase PAF speed [37,40–47] as well as pain thresholds and tolerance [48–52].” This has been changed to read: “Because evidence suggests that nicotine can modulate PAF, where both nicotine and smoking increase PAF speed [37,40–47], we chose nicotine to assess our aim of whether changes in PAF mediate changes in pain in a ‘mediation by design’ approach [48]. In addition, given evidence that nicotine may increase experimental pain thresholds and tolerance [49–53], nicotine could also influence pain ratings during tonic pain.”

(2) As mentioned above, the OSF page is not accessible.

We apologise for this. We had not realised that the pre-registration was under embargo, but we have now made it available.

(3) I generally struggle with the authors' approach to investigating alpha. With the approach the authors used to detect peak alpha frequency it might be that the alpha signal may just show such a low amplitude that it is impossible to reliably detect it at electrode level. In my view, the approach is not accurate enough, which can be seen by the "jagged" shape of the individual alpha peak frequency. In my view, a source separation technique would have been more useful. I wonder which of the known cortical alphas contributes to the effects the authors have reported previously: occipital, mu rhythms projections or something else? A source separation approach disentangles the different alphas and will increase the SNR. My suggestion would be to work on ICA components or similar approaches. The advantage is that the components are almost completely free of any artefacts. ICAs could be run on the entire data or separately for each individual. In the latter case, it might be that some participants do not exhibit any alpha component.

We appreciate your thoughtful consideration of our approach to investigating alpha. The calculation of PAF involves various methods and analysis steps across the literature (Corcoran et al., 2018; Gil Avila et al., 2023; McLain et al., 2022). Your query about which known cortical alphas contribute to reported effects is important. Initially focusing on a sensorimotor component from an ICA in Furman et al., 2018, subsequent work from our labs suggested a broader relationship between PAF and pain across the scalp (Furman et al., 2019; Furman et al., 2020; Millard et al., 2022), and a desire to conduct analyses at the sensor level in order to improve the reproducibility of the methods (Furman et al., 2020). However, based on your comment we have made several additions to the manuscript, including: explaining why we did not use manual ICA methods, suggest this for future research, and added an exploratory analysis using a recently developed automated pipeline that selects components based on the presence of a peak in the alpha range and alignment with a predefined template topography representing activity from occipital or motor sites.

While we acknowledge that ICA components can offer a better signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and possibly smoother spectral plots, we opted for our chosen method to avoid potential bias inherent in deciding on a component following source separation. The desire for a quick, automated, replicable, and unbiased pipeline, crucial for potential clinical applications of PAF as a biomarker, influenced this decision. At the time of analysis registration, automated methods for deciding which alpha components to extract following ICA were not apparent. We have now added this reasoning to Methods.

“Contrary to some previous studies that used ICA to isolate sensory region alpha sources (Furman et al., 2018; De Martino et al., 2021; Valentini et al., 2022), we used pre-determined sensor level ROIs to improve reproducibility and reduce the potential for bias when individually selecting ICA components. Using sensor level ROIs may decrease the signal-to-noise ratio of the data; however, this approach has still been effective for observing the relationship between PAF and experimental pain (Furman et al., 2019; Furman et al., 2020).”

We have also added use of ICA and development of methods as a suggestion for future research in the discussion:

“Additionally, the use of global PAF may have introduced mediation measurement error into our mediation analysis. The spatial precision used in the current study was based on previous literature on PAF as a biomarker of pain sensitivity, which have used global and/or sensorimotor ROIs (Furman et al., 2018; Furman et al., 2020). Identification and use of the exploratory electrode clusters found in this study could build upon the current work (e.g., Furman et al., 2021). However, exploratory analysis of the clusters found in the present analysis demonstrated no influence on mediation analysis results (Supplementary Materials 3.8-3.10). Alternatively, independent component analysis (ICA) could be used to identify separate sources of alpha oscillations (Choi et al., 2005), as used in other experimental PAF-pain studies (Furman et al., 2018; Valentini et al., 2022), which could aid to disentangle the potential relevance of different alpha sources in the PAFpain relationship. Although this comes with the need to develop more reproducible and automated methods for identifying such components.”

The specific location or source of PAF that relates to pain remains unclear. Because of this, we did employ an exploratory cluster-based permutation analysis to assess the potential for variations in the presence of PAF changes across the scalp at sensor level, and emphasise that location of PAF change could be explored in future. However, we have now conducted the mediation analysis (difference score 2W-LCS model) using averages from the data-driven parietal cluster, frontal cluster, and both clusters together. For these we see a stronger effect of gum on PAF change, which was expected given the data driven approach of picking electrodes. There was still a total and direct effect of nicotine on pain during the PHP model, but still no indirect effect via change in PAF. For the CPA models, there were still no significant total, direct, or indirect effects of nicotine on CPA ratings. Therefore, using these data-driven clusters did not alter results compared to the model using the global PAF variable.

The reader has been directed to this supplementary material so:

“The potential mediating effect of this change in PAF on change in PHP and CPA was explored (not pre-registered) by averaging within each cluster (central-parietal: CP1, CP2, Cpz, P1, P2, P3, P4, Pz, POz; right-frontal: F8, FT8, FT10) and across both clusters. This averaging across electrodes produced three new variables, each assessed in relation to mediating effects on PHP and CPA ratings. The resulting in six exploratory mediation analysis (difference score 2W-LCS) models demonstrated minimal differences from the main analysis of global PAF (8-12 Hz), except for the

expected stronger effect of nicotine on change in PAF (bs = 0.11-0.14, ps < .003; Supplementary

Materials 3.8-3.10).”

Moreover, our team has been working on an automated method for selecting ICA components, so in response to your comment we assessed whether using this method altered the results of the current analysis. The in-depth methodology behind this new automatic pipeline will be published with a validation from some co-authors in the current collaboration in due course. At present, in summary, this automatic pipeline conducts independent component analysis (ICA) 10 times for each resting state, and selects the component with the highest topographical correlation to a template created of a sensorimotor alpha component from Furman et al., (2018).

The results of the PHP or CPA mediation models were not substantially different using the PAF calculated from independent components than that using the global PAF. For the PHP model, the total effect (b = -0.648, p = .033) and direct effects (b = -0.666, p = .035) were still significant, and there was still no significant indirect effect (b = 0.018, p = .726). The general fit was reduced, as although the CFI was above 0.90, akin to the original model, the RMSEA and SRMR were not below 0.08, unlike the original models (Little, 2013). For the CPA model, there were still no significant total (b = -0.371, p = .357), direct (b = -0.364, p = .386), or indirect effects (b = -0.007, p = .906), and the model fit also decreased, with CFI below 0.90 and RMSEA and SRMR above 0.08. See supplementary material (3.11). Note that still no correlations were seen between this IC sensorimotor PAF and pain (PHP: r = 0.11, p = .4; CPA: r = -0.064, p = .63).

Interestingly, in both models, there was now no longer a significant a-path (PHP: b = 0.08, p =

0.292; CPA: b = 0.039, p = 0.575), unlike previously observed (PHP: b = 0.085, p = 0.018; CPA: b = 0.089, p = 0.011). We interpret this as supporting the previously highlighted difference between finding an effect on PAF globally but not in a sensorimotor ROI (and now a sensorimotor IC), justifying the exploratory CBPA and the suggestion in the discussion to explore methodology.

We understand that this analysis does not fully uncover the reviewer’s question in which they wondered which of the known cortical alphas contributes to the effects reported in our previous work. However, we consider this exploration to be beyond the scope of the current paper, as it would be more appropriately addressed with larger datasets or combinations of datasets, potentially incorporating MEG to better disentangle oscillatory sources. The highlighted differences seen between global PAF, sensorimotor ROI PAF, sensorimotor IC PAF, as well as the CBPA of PAF changes provide ample directions for future research to build upon: 1) which alpha (sensor or source space) are related to pain, 2) how are these alpha signals represented robustly in a replicable way, and 3) which alpha (sensor or source space) are manipulable through interventions. These are all excellent questions for future studies to investigate.

The below text has been added to the Discussion:

In-house code was developed to compare a sensorimotor component to the results presented in this manuscript (Supplementary Material 3.11), showing similar results to the sensorimotor ROI mediation analysis presented here. However, examination of which alpha - be it sensor or source space - are related to pain, how they can be robustly represented, and how they can be manipulated are ripe avenues for future study.

(4) I have my doubts that you can get a reliable close to bell-shaped amplitude distribution for every participant. The argument that the peak detection procedure is hampered by the high-amplitude lower frequency can be easily solved by subtracting the "slope" before determining the peak. My issue is that the entire analysis is resting on the assumption that each participant has a reliable alpha effect at electrode level. This is not the case. Non-alpha participants can severely distort the statistics. ICA-based analyses would be more sensitive but not every participant will show alpha. You may want to argue with robust group effects but In my view, every single participant counts, particularly for this type of data analysis, where in the case of a low SNR the "peak" can easily shift to the extremes. In case there is an alpha effect for a specific subject, we should see a smooth bump in the frequency spectrum between 8 and 12 12Hz. Anything beyond that is hard to believe. The long stimulation period allows a broad FFT analysis window with a good frequency resolution in order to detect the alpha frequency bump.

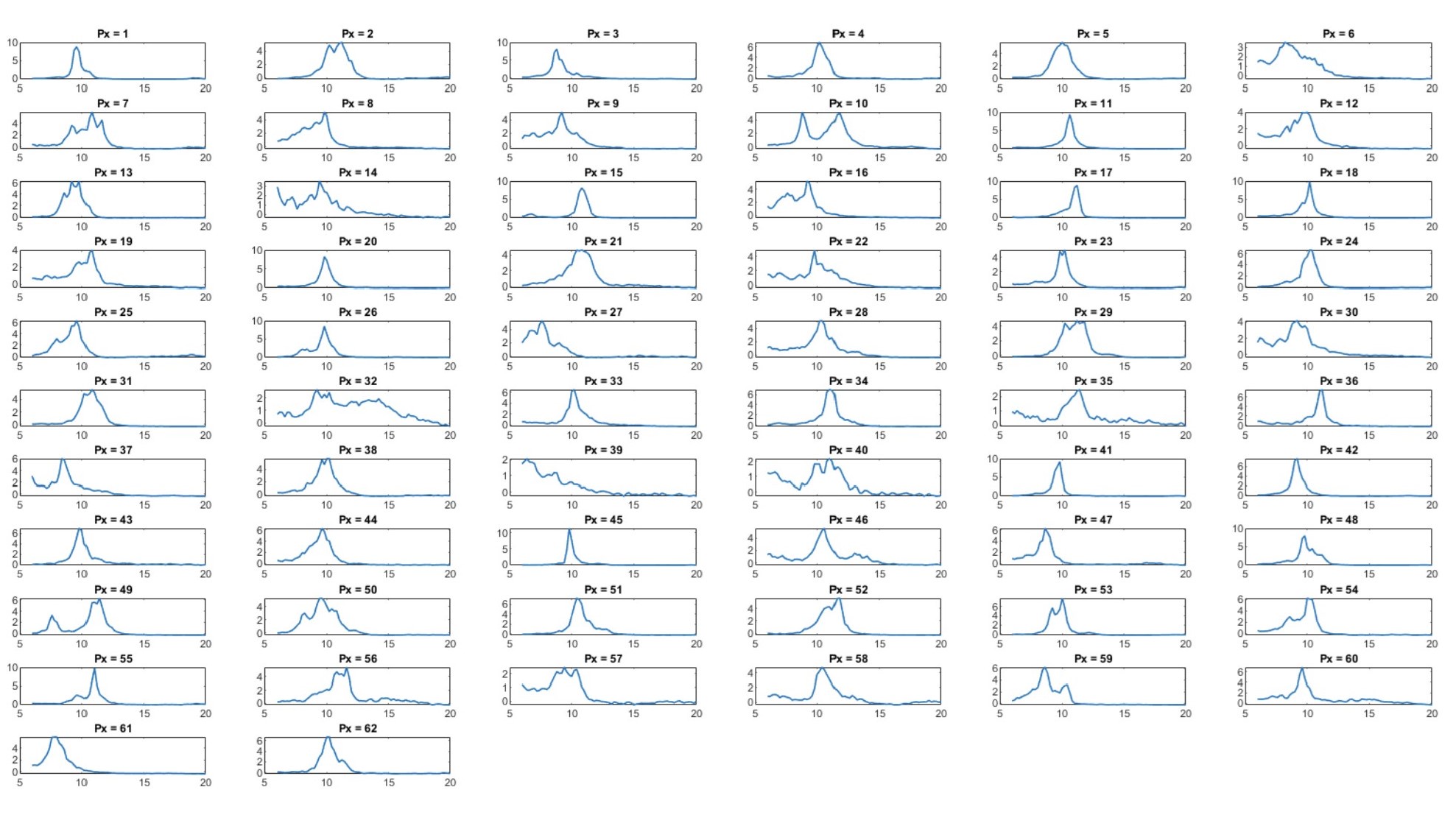

The reviewer is correct that non-alpha participants can distort the statistics. We did visually assess the EEG of each individual’s spectra at baseline to establish the presence of global peaks, as we believe this is good practice to aid understanding of the data. Please see Author response image 1 for individual spectra seen at baseline. Although not all participants had a ‘smooth bump in the frequency spectrum between 8 and 12 Hz’, we prefer to not apply/necessitate this assumption to our data. Chiang et al., (2011) suggest that ~3% of individuals do not have a discernible alpha peak, and in our data we observed only one participant without a very obvious spectral peak (px-39). But, this participant does have enough activity within the alpha range to identify PAF by the CoG method (i.e. not just flat spectra and activity on top of 1/f characteristics). Without a pre-registered and standardised decision process to remove such a participant in place, we opted to not remove any participants to avoid curation of our data.

Author response image 1.

(5) I find reports on frequent channel rejections reflect badly on the data quality. Bad channels can be avoided with proper EEG preparation. EEG should be continuously monitored during recording in order to obtain best data quality. Have any of the ROI channels been rejected?

We appreciate your attention to the channel rejection. We believe that the average channels removed (0.94, 0.98, 0.74, and 0.87 [range: 0-4] for each of the four resting states out of 64 channels) does not suggest overly frequent rejection, as it was less than one electrode on average and the numbers are below the accepted number of bad channels to remove/interpolate (i.e. 10%) in EEG pipelines (Debnath et al., 2020; Kayhan et al., 2022). To maintain data quality, consistently poor channels were identified and replaced over time. We hope you will accept our transparency on this issue and note that by stating how channel removal decisions were made (i.e. 8 or more deviations) and reporting the number of channels removed, we adhere to the COBIDAS guidelines (Pernet et al., 2018; 2020).

During analysis, cases of sensorimotor ROI channels being rejected were noted and are now specified in our manuscript. “Out of 248 resting states recorded, 14 resting states had 4 ROI channels instead of 5. Importantly, no resting state had fewer than 4 channels for the sensorimotor ROI.”

Note, we also realised that we had not specified that we did interpolate channels for the cluster based permutation analysis. This has been corrected with the following sentence:

“Removed channels were not interpolated for the pre-registered global and sensorimotor ROI averaged analyses, but were interpolated for an exploratory cluster based permutation analysis using the nearest neighbour average method in `Fieldtrip`.”

(6) I have some issues buying the authors' claims that there is an effect of nicotine on prolonged pain. By looking at the mean results for the nicotine and placebo condition, this can not be right. What was the point in including the variables in the equation? In my view, in this within-subject design the effect of nicotine should be universal, no matter what gender, age, or depression. The unconditional effect of nicotine is close to zero. I can not get my head around how any of the variables can turn the effects into significance. There must be higher or lower variable scores that might be related to a higher or lower effect on nicotine. The question is not to consider these variables as a nuisance but to show how they modulate the pain-related effect of nicotine treatment. Still, the overall nicotine effect of the entire group is basically zero.

Another point is that for within-subject analyses even tiny effects can become statistically significant if they are systematically in one direction. This might be the case here. There might be a significant effect of nicotine on pain but the actual effect size (5.73 vs. 5.78) is actually not interpretable. I think it would be interesting for the reader how (in terms of pain rating difference) each of the variables can change the effect of nicotine.

Thank you for your comments. We recognize the concern about interpreting the effect of nicotine on prolonged pain solely based on mean results, and in fact wish to discourage this approach. It's crucial to note that both PAF and pain are highly individual measures (i.e. high inter-individual variance), necessitating the use of random intercepts for participants in our analyses to acknowledge the inherent variability at baseline across participants. Including random intercepts rather than only considering the means helps address the heterogeneity in baseline levels among participants. We also recognise that displaying the mean PHP ratings for all participants in Table 2 could be misleading, firstly because these means do not have weight in an analysis that takes into account a random-effects intercept for participants, and secondly because two participants (one from each group) did not have post-gum PHP assessments and were not included in the mediation analysis due to list-wise deletion of missing data. Therefore, to reduce the potential for misinterpretation, we have added extra detail to display both the full sample and CPA mediation analysis (i.e. N=62) and the data used for PHP mediation analysis (i.e. n=60) in Table 2. We hope that the extra details added to this table will help the readers interpretation of results.

In light of this, we have also altered the PAF Table 3 to reflect both the pre-post values used for the CPA mediation and baseline correlations with CPA and PHP pain (i.e. N=62), and the pre-post values used for the PHP mediation (i.e. n=60).

It is inherently difficult to visualise the findings of a mediation analysis with confounding variables that also used latent change scores (LCS) and random-effect intercepts for participants. LCS was specifically used because of issues of regression to the mean that occur if you calculate a straightforward ‘difference-score’, therefore calculating the difference in order to demonstrate the results of the statistical model in a figure, for example, does not provide a full description of the data assessed (Valente & McKinnon, 2017). Nevertheless, if we look at the data descriptively with this in mind, then calculating the change in PHP ratings does indicate that, for the nicotine group, the mean change in PHP ratings was -0.047 (SD = 1.05, range: -4.13, 1.45). Meanwhile, for the placebo group the mean change in PHP ratings was 0.33 (SD = 0.75, range: -1.37, 1.66). Therefore suggesting a slight decrease in pain ratings on average for the nicotine group compared to a slight increase on average for the placebo group. With control for pre-determined confounders, we found that the latent change score was -0.63 lower for the nicotine group compared to the control group (i.e. the direct effect of nicotine on change in pain).

If the reviewer is only discussing the effect of nicotine on pain, we do not believe that this effect ‘should be universal’. There is clear evidence that effects of nicotine on other measures can vary greatly across individuals (Ettinger et al., 2009; Falco & Bevins, 2015; Pomerleau et al., 1995). Our intention would not be to propose a universal effect but to understand how these variables may influence nicotine's impact on pain for individuals. Here we focus on the effects of nicotine on PAF and pain sensitivity, but attempted to control for the potential influence of these other confounding factors. Therefore, our statistical approach goes beyond mean values, incorporating variables like sex at birth, age, and depression to control for and explore potential modulating factors. Control for confounding factors is an important aspect of mediation analysis (Lederer et al., 2019; VanderWeele, 2019).

Regarding the seemingly small effect size, we understand your concern. Indeed ‘tiny effects can become statistically significant if they are systematically in one direction’, which may be what we see in this analysis. We do not agree that the effect is ‘not interpretable’, rather that it should be interpreted in light of its small effect size (effect size being the beta coefficient in our analysis, rather than the mean group difference). We agree on the importance of considering practical significance alongside statistical significance and hope to conduct additional experiments and analyses in future to elucidate the contribution of each variable to the subtle and therefore not entirely conclusive overall effect you mention.

Your feedback on this is valuable, and we have ensured a more detailed discussion in the revised manuscript on how these factors should be interpreted alongside some additional post-hoc analyses of confounding factors that were significant in our mediation, with the note that investigation of these interactions is exploratory. We had already discussed the potential contribution of sex on the effect of nicotine on PAF, with exploratory post-hoc analysis on this included in supplementary materials. In addition, we have now added an exploratory post-hoc analysis on the potential contribution of stress on the effect of nicotine on pain. This then shows the stratified effects by the covariates that our model suggest are influencing change in PAF and pain.

Results edits:

“There was also a significant effect of perceived stress at baseline on change in PHP ratings when controlling for group allocation and other confounding variables (b = -0.096, p = .048, bootstrapped 95% CI: [-0.19, -0.000047]), where higher perceived stress resulted in larger decreases in PHP ratings (see Supplementary Material 3.3 for post-hoc analysis of stress).”

Supplementary material addition:

“3.3 Exploratory analysis of the influence of perceived stress on the effects of nicotine on change in PHP ratings “

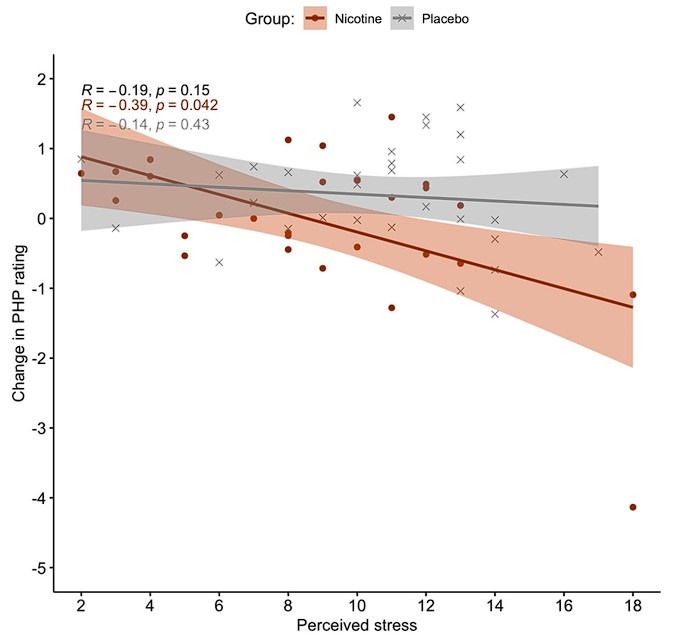

“Due to the significant estimated effects of perceived stress on change in PHP ratings in the 2WLCS mediation model, we also explored post-hoc effects of stress on change in PHP ratings. We found that there is strong evidence for a negative correlation between stress and change in PHP rating within the nicotine group (n = 28, r = −0.39, BF10 = 13.65; Figure 3) that is not present in the placebo group, with equivocal evidence (n = 32, r = −0.14, BF10 = 0.46). This suggests that those with higher baseline stress who had nicotine gum experienced greater decreases in PHP ratings. Note that there was less, but still sufficient evidence for this relationship within the nicotine group when the participant who was a potential outlier for change in PHP rating was removed (n = 27, r = −0.32, BF10 = 1.45). “

Author response image 2.

Spearman correlations od baseline perceived stress with the change in phasic heat pain (PHP) ratings, suggest strong evidence for a negative relationship for the nicotine gum groupin orange (n=28; BF10=13.65) but not for the placebo group in grey (n=32; BF10=0.46). Regression lines and 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion edits:

“For example, in addition to the effect of nicotine on prolonged heat pain ratings, our results suggest an effect of stress on changes in heat pain ratings, with those self-reporting higher stress at baseline having greater reductions in pain. Our post-hoc analysis suggested that this relationship between higher stress and larger decrease in PHP ratings was only present for the nicotine group (Supplementary Material 3.3). As stress is linked to nicotine use [69,70] and pain [71–73], these interactions should be explored in future.”

(7) Is the differential effect of nicotine vs. placebo based on the pre vs. post treatment effect of the placebo condition or on the pre vs. post effect of the nicotine treatment? Can the mediation model be adapted and run for each condition separately? The placebo condition seems to have a stronger effect and may have driven the result.

Thank you for your comments. In our mediation analysis, the differential effect of nicotine vs. placebo is assessed as a comparison between the pre-post difference within each condition. A latent change score (i.e. pre-post) is calculated for each condition (nicotine and placebo), and then the effect of being in the nicotine group (dummy coded as 1) is compared to being in the placebo group (dummy coded as 0). The comparison between conditions is needed for this model (Valente & MacKinnon, 2017), as we are assessing the change in PAF and pain in the nicotine group compared to the change in the placebo group.

However, to address your response, it is possible to simplify and assess the relationship between the change in peak alpha frequency (PAF) and change in pain within each gum group (nicotine and placebo) independently, without including the intervention as a factor. To do this, the mediation model can be simplified to regression analysis with latent change scores that focus purely on these relationships. The results of this can help to understand whether change in PAF influences change in pain within each group separately. As with the main analysis, we see no significant influence of change in PAF on change in pain while controlling for the same confounding variables within the nicotine group (Beta = -0.146 +/- 1.105, p = 0.895, 95% CI: -2.243, 2.429) or the placebo group (Beta = 0.730 +/- 2.061, p = 0.723, 95% CI: -4.177, 3.625).

When suggesting that the “the placebo condition seems to have a stronger effect and may have driven the result”, we believe you are referring to the increase in mean PHP ratings within the placebo group from pre (5.51 +/- 2.53) to post-placebo gum (5.84 +/- 2.67). Indeed there was a significant increase in pain ratings pre to post chewing placebo gum (t(31) = -2.53, p = 0.0165, 95% CI: -0.603, -0.0653), that was not seen after chewing nicotine gum (t(27) = 0.237, p = 0.81, 95% CI: -0.358, 0.452). In lieu of a control where no gum was chewed (i.e. simply a second pain assessment ~30 minutes after the first), we assume the gum without nicotine is a good reference that controls for the effect of time plus expectation of chewing nicotine gum. With this in mind, as we describe in our results, the change in PHP ratings is reduced in the nicotine group compared to the placebo group. Note that this phrasing keeps the effect of placebo on pain as our reference from which to view the effect of nicotine on pain. However, you are correct that we need to ensure we emphasise that the change in pain in the PHP group is reduced in comparison to the change seen after placebo.

We have not included these extra statistics in our revised manuscript, but hope that they aid the your understanding and interpretation of the included analyses and have highlighted these nuances in the discussion.

“However, we note that the observed effect of nicotine on pain was small in magnitude, and most prominent in comparison to the effect of placebo, where pain ratings increased after chewing, which brings into question whether this reduction in pain is meaningful in practice.”

(8) I would not dare to state that nicotine can function as an acute analgesic. Acute analgesics need to work for everyone. The average effect here is close to zero.

In light of your feedback, we have refined our language to avoid a sweeping assertion of universal analgesic effects and emphasize individual variability. Nicotine's role as a coping strategy for pain is acknowledged in the literature (Robinson et al., 2022), with the meta-analysis by Ditre et al. (2016) discussing its potential as an acute analgesic in humans, along with some evidence from animal research (Zhang et al., 2020). Our revised discussion underscores the need for further exploration into factors influencing nicotine's potential impact on pain. We have also specified the short-term nature of nicotine use in this context to distinguish acute effects from potential opposing effects after long-term use (Zhang et al., 2020).

“Short-term nicotine use is thought to have acute analgesic properties in experimental settings, with a review reporting that nicotine increased pain thresholds and pain tolerance [49]. In addition, research in a rat model suggests analgesic effects on mechanical thresholds after short-term nicotine use (Zhang et al., 2020). However, previous research has not assessed the acute effects of nicotine on prolonged experimental pain models. The present study found that 4 mg of nicotine reduced heat pain ratings during prolonged heat pain compared to placebo for our human participants, but that prolonged pressure pain decreased irrespective of which gum was chewed. Our findings are thus partly consistent with the idea that nicotine may have acute analgesic properties [49], although further research is required to explore factors that may influence nicotine’s potential impact on a variety of prolonged pain models. We further advance the literature by reporting this effect in a

model of prolonged heat pain, which better approximates the experience of clinical pain than short lasting models used to assess thresholds and tolerance [50]. However, we note that the observed effect of nicotine on pain was small in magnitude, and most prominent in comparison to the effect of placebo, where pain ratings increased after chewing, which brings into question whether this reduction in pain is meaningful in practice. Future research should examine whether effects on pain increase in magnitude with different nicotine administration regimens (i.e. dose and frequency).”

(9) Figures 2E and 2F are not particularly intuitive. Usually, the colour green in "jet" colour coding is being used for "zero" values. I would suggest to cut off the blue and use only the range between red green and red.

We have chosen to retain the current colour scale for several reasons. In our analysis, green represents the middle of the frequency range (approx 10 Hz in this case), and if we were to use green as zero, it would effectively remove both blue and green from the plot, resulting in only red shades. Additionally, we have provided a clear colour scale for reference next to the plot, which allows readers to interpret the data accurately. Our intention is to maintain clarity and precision in representing the data, rather than conforming strictly to conventional practices in color coding.

We believe that the current representation effectively conveys the results of our study while allowing readers to interpret the data within the context provided. Thank you again for your suggestion, and we hope you understand our reasoning in this matter.

(10) Did the authors do their analysis on the parietal ROI or on the pre-registerred ROI?

The analysis was conducted on the pre-registered sensorimotor ROI and on the global values. We have now also conducted the analysis with the regions suggested with the cluster based permutation analysis as requested by reviewer 2, comment 3.

(11) Point 3.2 in the discussion. I would be very cautious to discuss smoking and chronic pain in the context of the manuscript. The authors can not provide any additional knowledge with their design targeting non-smokers, acute nicotine and experimental pain. The information might be interesting in the introduction in order to provide the reader with some context but is probably misleading in the discussion.

We appreciate your perspective and agree with your caution regarding the discussion of smoking and chronic pain. While our study specifically targets non-smokers and focuses on acute nicotine effects in experimental pain, we understand the importance of contextual clarity. We have removed these points from the discussion to not mislead the reader.

Previously we wrote, and have removed: “For those with chronic pain, smoking and nicotine use is reported as a coping strategy for pain [52]; abstinence can increase pain sensitivity [48,50], and pain is thus seen as a barrier to smoking cessation due to fear of worsening pain [51,52]. Therefore, continued understanding of the acute effects of nicotine on models of prolonged pain could improve understanding of the role of nicotine and smoking use in chronic pain [49,51,52].”

(12) I very much appreciate section 3.3 of the discussion. I would not give up on PAF as a target to modulate pain. A modulation might not be possible in such a short period of experimental intervention. PAF might need longer and different interventions to gradually shift in order to attenuate the intensity of pain. As discussed by the authors themselves, I would also consider other targets for alpha analysis (as mentioned above not other electrodes or ROIs but separated sources.)

Thank you for your comments on section 3.3. We appreciate your recognition of the potential significance of PAF as a target for pain modulation. Your insights align with our considerations that the experimental intervention duration or type might be a limiting factor in observing substantial shifts in PAF to attenuate pain intensity. We had mentioned the use of the exploratory electrode clusters in future work, but have now also mentioned that the use of ICA to identify separate ICA sources may provide an alternative approach. See responses to your previous ICA comment regarding separate sources.

REFERENCES for responses to reviewer 2

Chiang, A. K. I., Rennie, C. J., Robinson, P. A., Van Albada, S. J., & Kerr, C. C. (2011). Age trends and sex differences of alpha rhythms including split alpha peaks. Clinical Neurophysiology, 122(8), 1505-1517.

Debnath, R., Buzzell, G. A., Morales, S., Bowers, M. E., Leach, S. C., & Fox, N. A. (2020). The Maryland analysis of developmental EEG (MADE) pipeline. Psychophysiology, 57(6), e13580.

Ettinger, U., Williams, S. C., Patel, D., Michel, T. M., Nwaigwe, A., Caceres, A., ... & Kumari, V. (2009). Effects of acute nicotine on brain function in healthy smokers and non-smokers: estimation of inter-individual response heterogeneity. Neuroimage, 45(2), 549-561.

Falco, A. M., & Bevins, R. A. (2015). Individual differences in the behavioral effects of nicotine: a review of the preclinical animal literature. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 138, 80-90.

Kayhan, E., Matthes, D., Haresign, I. M., Bánki, A., Michel, C., Langeloh, M., ... & Hoehl, S. (2022). DEEP: A dual EEG pipeline for developmental hyperscanning studies. Developmental cognitive neuroscience, 54, 101104.

Lederer, D. J., Bell, S. C., Branson, R. D., Chalmers, J. D., Marshall, R., Maslove, D. M., ... & Vincent, J. L. (2019). Control of confounding and reporting of results in causal inference studies. Guidance for authors from editors of respiratory, sleep, and critical care journals. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 16(1), 22-28.

Little TD. Longitudinal structural equation modeling. Guilford press; 2013.

Pernet, C., Garrido, M., Gramfort, A., Maurits, N., Michel, C. M., Pang, E., ... & Puce, A. (2018). Best practices in data analysis and sharing in neuroimaging using MEEG.

Pernet, C., Garrido, M. I., Gramfort, A., Maurits, N., Michel, C. M., Pang, E., ... & Puce, A. (2020). Issues and recommendations from the OHBM COBIDAS MEEG committee for reproducible EEG and MEG research. Nature neuroscience, 23(12), 1473-1483.

Pomerleau, O. F. (1995). Individual differences in sensitivity to nicotine: implications for genetic research on nicotine dependence. Behavior genetics, 25(2), 161-177.

Robinson, C. L., Kim, R. S., Li, M., Ruan, Q. Z., Surapaneni, S., Jones, M., ... & Southerland, W. (2022). The Impact of Smoking on the Development and Severity of Chronic Pain. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 26(8), 575-581.

Xia, J., Mazaheri, A., Segaert, K., Salmon, D. P., Harvey, D., Shapiro, K., ... & Olichney, J. M. (2020). Event-related potential and EEG oscillatory predictors of verbal memory in mild cognitive impairment. Brain communications, 2(2), fcaa213.

VanderWeele, T. J. (2019). Principles of confounder selection. European journal of epidemiology, 34, 211-219.

Valente, M. J., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2017). Comparing models of change to estimate the mediated effect in the pretest–posttest control group design. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 24(3), 428-450.

Vimolratana, O., Aneksan, B., Siripornpanich, V., Hiengkaew, V., Prathum, T., Jeungprasopsuk, W., ... & Klomjai, W. (2024). Effects of anodal tDCS on resting state eeg power and motor function in acute stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 21(1), 1-15.

Zhang, Y., Yang, J., Sevilla, A., Weller, R., Wu, J., Su, C., ... & Candiotti, K. A. (2020). The mechanism of chronic nicotine exposure and nicotine withdrawal on pain perception in an animal model. Neuroscience letters, 715, 134627.

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations For The Authors):

Introduction

(1) Rationale and link to chronic pain. I am not sure I agree with the statement "The ability to identify those at greater risk of developing chronic pain is limited". I believe there is an abundance of literature associating risk factors with the different instances of chronic pain (e.g., Mills et al., 2019). The fact that the authors cite studies involving potential neuroimaging biomarkers leads me to believe that they perhaps did not intend to make such a broad statement, or that they wanted to focus on individual prediction instead of population risk.

We thank the reviewer for the thought put into this comment. We did indeed wish to refer to individual prediction, but also realise that the focus on predicting pain might not be the most appropriate opening for this manuscript. Therefore, we have adjusted the below sentence to refer to the need to identify modifiable factors rather than the need to predict pain.

“Identifying modifiable factors that influence pain sensitivity could be a key step in reducing the presence and burden of chronic pain (van der Miesen et al., 2019; Davis et al., 2020; Tracey et al., 2021).”

(2) The statement "Individual peak alpha frequency (PAF) is an electro-physiological brain measure that shows promise as a biomarker of pain sensitivity, and thus may prove useful for predicting chronic pain development" is a non sequitur. PAF may very well be a biomarker of pain sensitivity, but the best measures of pain sensitivity we have (selfreported pain intensity ratings) in general are not in themselves predictive of the development of chronic pain. Conversely, features that are not related to pain sensitivity could be useful for predicting chronic pain (e.g., Tanguay-Sabourin et al., 2023).

We agree that it is essential to acknowledge that self-reported pain intensity ratings alone are not definitive predictors of chronic pain development. To align with this, we have revised the sentence, removing the second clause to avoid overstatement. The adjusted sentence now reads, "Individual peak alpha frequency (PAF) is an electrophysiological brain measure that shows promise as a biomarker of pain sensitivity."

(3) Finally, some of the statements in the discussion comparing a tonic heat pain model with chronic neuropathic pain might be an overstatement. Whereas it is true that some of the descriptors are similar, the time courses and mechanisms are vastly different.

We appreciate this comment, and agree that it is difficult to compare the heat pain model used to clinical neuropathic pain. This was an oversight and with further understanding we have removed this comment from the introduction and the discussion:

“In parallel, we saw no indication of a relationship between PAF and pain ratings during CPA. The introduction of the CPA model, specifically calibrated to a moderate pain threshold, provides further support for the notion that the relationship between PAF and pain is specific to certain pain types [17,28]. Prolonged heat pain was pre-dominantly described as moderate/severe shooting, sharp, and hot pain, whereas prolonged pressure pain was predominantly described as mild/moderate throbbing, cramping, and aching in the present study. It is possible that the PAF–pain relationship is specific to particular pain models and protocols [12,17].”

Methodology

(4) or the benefit of good science. However, I am compelled to highlight that I could not access the preregistered files, even though I waited for almost two weeks after requesting permission to do so. This was a problem on two levels: the main one is that I could not check the hypothesized effect sizes of the sample size estimation, which are not only central to my review, and in general negate all the benefits that should go with preregistration (i.e., avoiding phacking, publication bias, data dredging, HARKing, etc.). The second one is that I had to provide an email address to request access. This allows the authors to potentially identify the reviewers. Whereas I have no issues with this and I support transparent peer review practices (https://elifesciences.org/inside-elife/e3e90410/increasingtransparency-in-elife-s-review-process), I also note that this might condition other reviewers.

We apologise for this. We had not realised that the pre-registration was under embargo, but we have now made it available.

Interpretation of results

(5)To be perfectly clear, I trust the results of this study more than some of the cited studies regarding nicotine and pain because it was preregistered, the sample size is considerably larger, and it seems carefully controlled. I just do not agree with the interpretation of the results, stated in the first paragraph of the Discussion. Quoting J. Cohen, "The primary product of a research inquiry is one or more measures of effect size, not P values" (Cohen, 1990). As I am sure the authors are aware of, even tiny differences between conditions, treatments or groups will eventually be statistically significant given arbitrarily large sample sizes. What really matters then is the magnitude of these differences. In general, the authors hypothesize on why there were no differences on the pressure pain model, and why decreases in heat pain were not mediated by PAF, but do not seem to consider the possibility that the intervention just did not cause the intended effect on the nociceptive system, which would be a much more straightforward explanations for all observations.

While acknowledging and agreeing with the concern that 'even tiny differences between conditions, treatments, or groups will eventually be statistically significant given arbitrarily large sample sizes,' it's crucial to clarify that our sample size of N=62 does not fall into the category of arbitrarily large. We carefully considered the observed outcomes in the pressure pain model and the lack of PAF mediation in heat pain, as dictated by our statistical approach and the obtained results.

The suggestion of a straightforward explanation aligning with the intervention not causing the intended effect on the nociceptive system is a valid consideration. We did contemplate the possibility of a false positive, emphasising this in the limitations of our findings and the need for replication to draw stronger conclusions to follow up this initial study.

(6) In this regard, I do not believe that an average *increase* of 0.05 / 10 (Nicotine post - pre) can be considered a "reduction of pain ratings", regardless of the contrast with placebo (average increase of 0.24 / 10). This tiny effect size is more relevant in the context of the considerable inter-individual variation, in which subjects scored the same heat pain model anywhere from 1 to 10, and the same pressure pain model anywhere from 1 to 8.5. In this regard, the minimum clinically or experimentally important differences (MID) in pain ratings varies from study to study and across painful conditions but is rarely below 1 / 10 in a VAS or NRS scale, see f. ex. (Olsen et al., 2017). It is not my intention to question whether nicotine can function as an acute analgesic in general (as stated in the Discussion), but instead, if it worked as such under these very specific experimental conditions. I also acknowledge that the authors note this issue in two lines in the Discussion, but I believe that this is not weighed properly.

We appreciate your perspective on the interpretation of the effect size, and we understand the importance of considering it in the context of individual variation.

As also discussed in response to comment 6 From reviewer 2, we recognize the concern about interpreting the effect of nicotine on prolonged pain solely based on mean results, and in fact wish to discourage this approach. It's crucial to note that both PAF and pain are highly individual measures (i.e. high inter-individual variance), necessitating the use of random intercepts for participants in our analyses to acknowledge the inherent variability at baseline across participants. Including random intercepts rather than only considering the means helps address the heterogeneity in baseline levels among participants. We also recognise that displaying the mean PHP ratings for all participants in Table 2 could be misleading, firstly because these means do not have weight in an analysis that takes into account a random-effects intercept for participants, and secondly because two participants (one from each group) did not have post-gum PHP assessments and were not included in the mediation analysis due to list-wise deletion of missing data. Therefore, to reduce the potential for misinterpretation, we have added extra detail to display both the full sample and CPA mediation analysis (i.e. N=62) and the data used for PHP mediation analysis (i.e. n=60) in Table 2. We hope that the extra details added to this table will help the readers interpretation of results.

Moreover, we have made sure refer to the comparison with the placebo group when discussing the reduction or decrease in pain seen in the nicotine group, for example:

“2) nicotine reduced prolonged heat pain intensity but not prolonged pressure pain intensity compared to placebo gum;”

“The nicotine group had a decrease in heat pain ratings compared to the placebo group and increased PAF speed across the scalp from pre to post-gum, driven by changes at central-parietal and right-frontal regions.”

We have kept our original comment of whether this effect on pain is meaningful in practice to refer to the minimum clinically or experimentally important differences in pain ratings as highlighted by Olsen et al., 2017.

“While acknowledging the modest effect size, it’s essential to consider the broader context of our study’s focus. Assessing the clinical relevance of pain reduction is pertinent in applications involving the use of any intervention for pain management [69]. However, from a mechanistic standpoint, particularly in understanding the implications of and relation to PAF, the specific magnitude of the pain effect becomes less pivotal. Nevertheless, future research should examine whether effects on pain increase in magnitude with different nicotine administration regimens (i.e. dose and frequency).”

(7) In line with the topic of effect sizes, average effect sizes for PAF in the study cited in the manuscript range from around 1 Hz (Boord et al., 2008; Wydenkeller et al., 2009; Lim et al., 2016), to 2 Hz (Foulds et al., 1994), compared with changes of 0.06 Hz (Nicotine post - pre) or -0.01 Hz (Placebo post - pre). MIDs are not so clearly established for peak frequencies in EEG bands, but they should be certainly larger than some fractions of a Hertz (which is considerably below the reliability of the measurement).

We appreciate your care of these nuances. We acknowledge the differences in effect sizes between our study and those referenced in the manuscript. Given the current state of the literature, it's noteworthy that ‘MIDs’ for peak frequencies in EEG bands, particularly PAF changes, are not clearly established, other than a recent publication suggesting that even small changes in PAF are reliable and meaningful (Furman et al., 2021). In light of this, we have addressed the uncertainty around the existence and determination of MIDs in our revision, highlighting the need for further research in this area.

In addition, our study employed a greater frequency resolution (0.2 Hz) compared to some of the referenced studies, with approximately 0.5 Hz resolution (Boord et al., 2008; Wydenkeller et al., 2009; Foulds et al., 1994). This improved resolution allows for a more precise measurement of changes in PAF. Considering this, it is plausible that studies with lower resolution might have conflated increases in PAF, and our higher resolution contributes to a more accurate representation of the observed changes.

We have also incorporated this insight into the manuscript, emphasising the methodological advancements in our study and their potential impact on the interpretation of PAF changes. Thank you for your thoughtful feedback.

“The ability to detect changes in PAF can be considerably impacted by the frequency resolution used during Fourier Transformations, an element that is overlooked in recent methodological studies on PAF calculation [16,95]. Changes in PAF within individuals might be obscured or conflated by lower frequency resolutions, which should be considered further in future research.”

(8) The authors also ran alternative statistical models to analyze the data and did not find consistent results in terms of PHP ratings (PAF modulation was still statistically significantly different). The authors attribute this to the necessity of controlling for covariates. Now, considering the effects sizes, aren't these statistically significant differences just artifacts stemming from the inclusion of too many covariates (Simmons et al., 2011)? How much influence should be attributable to depression and anxiety symptoms, stress, sleep quality and past pain, considering that these are healthy volunteers? Should these contrasting differences call the authors to question the robustness of the findings (i.e., whether the same data subjected to different analysis provides the same results), particularly when the results do not align with the preregistered hypothesis (PAF modulation should occur on sensorimotor ROIs)?

Thank you for your comments on our alternative statistical models. By including these covariates, we aim to provide a more nuanced understanding of the complexities within our data by considering their potential impact on the effects of interest. The decision to include covariates was preregistered (apologies again that this was not available) and made with consideration of balancing model complexity and avoiding potential confounding. Moreover, we hope that the insights gained from these analyses will offer valuable information about the behaviour of our data and aid future research in terms of power calculations, expected variance, and study design.

(9) Beyond that, I believe in some cases that the authors overreach in an attempt to provide explanations for their results. While I agree that sex might be a relevant covariate, I cannot say whether the authors are confirming a pre-registered hypothesis regarding the gender-specific correlation of PAF and pain, or if this is just a post hoc subgroup analysis. Given the large number of analyses performed (considering the main document and the supplementary files), caution should be exercised on the selective interpretation of those that align with the researchers' hypotheses.

We chose to explore the influence of sex on the correlation between PAF and pain, because this has also been investigated in previous publications of the relationship (Furman et al., 2020). We state that the assessment by sex is exploratory in our results on p.17: “in an exploratory analysis of separate correlations in males and females (Figure 5, plot C)”. For clarity regarding whether this was a pre-registered exploration or not, we have adjusted this to be: “in an exploratory analysis (not pre-registered) of separate correlations in males and females (Figure 5, plot C), akin to those conducted in previous research on this topic (Furman et al., 2020),

We have made sure to state this in the discussion also. Therefore, when we previously said on p.22:

“Regarding the relationship between PAF and pain at baseline, the negative correlation between PAF and pain seen in previous work [7–11,15] was only observed here for male participants during the PHP model for global PAF.” We have now changed this to: “Regarding the relationship between PAF and pain at baseline, the negative correlation between PAF and pain seen in previous work [7– 11,15] was only observed here for male participants during the PHP model for global PAF in an exploratory analysis.”

Please also note that we altered the colour and shape of points on the correlation plot (Figure 5 in initial submission), the male brown was changed to a dark brown as we realised that the light brown colour was difficult to read. The shape was then changed for male points so that the two groups can be distinguished in grey-scale.

Overall, your thoughtful feedback is instrumental in refining the interpretation of our findings, and we look forward to presenting a more comprehensive and nuanced discussion. Thank you for your comments.

REFERENCES for responses to reviewer 3

Arendt-Nielsen, L., & Yarnitsky, D. (2009). Experimental and clinical applications of quantitative sensory testing applied to skin, muscles and viscera. The Journal of Pain, 10(6), 556-572.

Chowdhury, N. S., Skippen, P., Si, E., Chiang, A. K., Millard, S. K., Furman, A. J., ... & Seminowicz, D. A. (2023). The reliability of two prospective cortical biomarkers for pain: EEG peak alpha frequency and TMS corticomotor excitability. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 385, 109766.

Fishbain, D. A., Lewis, J. E., & Gao, J. (2013). Is There Significant Correlation between SelfReported Low Back Pain Visual Analogue Scores and Low Back Pain Scores Determined by Pressure Pain Induction Matching?. Pain practice, 13(5), 358-363.

Furman, A. J., Prokhorenko, M., Keaser, M. L., Zhang, J., Chen, S., Mazaheri, A., & Seminowicz, D. A. (2021). Prolonged pain reliably slows peak alpha frequency by reducing fast alpha power.

bioRxiv, 2021-07.

Heitmann, H., Ávila, C. G., Nickel, M. M., Dinh, S. T., May, E. S., Tiemann, L., ... & Ploner, M. (2022). Longitudinal resting-state electroencephalography in patients with chronic pain undergoing interdisciplinary multimodal pain therapy. Pain, 163(9), e997.

McLain, N. J., Yani, M. S., & Kutch, J. J. (2022). Analytic consistency and neural correlates of peak alpha frequency in the study of pain. Journal of neuroscience methods, 368, 109460.

Ngernyam, N., Jensen, M. P., Arayawichanon, P., Auvichayapat, N., Tiamkao, S., Janjarasjitt, S., ... & Auvichayapat, P. (2015). The effects of transcranial direct current stimulation in patients with neuropathic pain from spinal cord injury. Clinical Neurophysiology, 126(2), 382-390.

Parker, T., Huang, Y., Raghu, A. L., FitzGerald, J., Aziz, T. Z., & Green, A. L. (2021). Supraspinal effects of dorsal root ganglion stimulation in chronic pain patients. Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface, 24(4), 646-654.

Petersen-Felix, S., & Arendt-Nielsen, L. (2002). From pain research to pain treatment: the role of human experimental pain models. Best Practice & Research Clinical Anaesthesiology, 16(4), 667680.

Sarnthein, J., Stern, J., Aufenberg, C., Rousson, V., & Jeanmonod, D. (2006). Increased EEG power and slowed dominant frequency in patients with neurogenic pain. Brain, 129(1), 55-64.

Sato, G., Osumi, M., & Morioka, S. (2017). Effects of wheelchair propulsion on neuropathic pain and resting electroencephalography after spinal cord injury. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 49(2), 136-143.

Sufianov, A. A., Shapkin, A. G., Sufianova, G. Z., Elishev, V. G., Barashin, D. A., Berdichevskii, V. B., & Churkin, S. V. (2014). Functional and metabolic changes in the brain in neuropathic pain syndrome against the background of chronic epidural electrostimulation of the spinal cord. Bulletin of experimental biology and medicine, 157(4), 462-465.