Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Summary:

UGGTs are involved in the prevention of premature degradation for misfolded glycoproteins, by utilizing UGGT-KO cells and a number of different ERAD substrates. They proposed a concept by which the fate of glycoproteins can be determined by a tug-of-war between UGGTs and EDEMs.

Strengths:

The authors provided a wealth of data to indicate that UGGT1 competes with EDEMs, which promotes glycoprotein degradation.

Weaknesses:

Less clear, though, is the involvement of UGGT2 in the process. Also, to this reviewer, some data do not necessarily support the conclusion.

Major criticisms:

(1) One of the biggest problems I had on reading through this manuscript is that, while the authors appeared to generate UGGTs-KO cells from HCT116 and HeLa cells, it was not clearly indicated which cell line was used for each experiment. I assume that it was HCT116 cells in most cases, but I did not see that it was clearly mentioned. As the expression level of UGGT2 relative to UGGT1 is quite different between the two cell lines, it would be critical to know which cells were used for each experiment.

Thank you for this comment. We have clarified this point, especially in the figure legends.

(2) While most of the authors' conclusion is sound, some claims, to this reviewer, were not fully supported by the data. Especially I cannot help being puzzled by the authors' claim about the involvement of UGGT2 in the ERAD process. In most of the cases, KO of UGGT2 does not seem to affect the stability of ERAD substrates (ex. Fig. 1C, 2A, 3D). When the author suggests that UGGT2 is also involved in the ERAD, it is far from convincing (ex. Fig. 2D/E). Especially because now it has been suggested that the main role of UGGT2 may be distinct from UGGT1, playing a role in lipid quality control (Hung, et al., PNAS 2022), it is imperative to provide convincing evidence if the authors want to claim the involvement of UGGT2 in a protein quality control system. In fact, it was not clear at all whether even UGGT1 is also involved in the process in Fig. 2D/E, as the difference, if any, is so subtle. How the authors can be sure that this is significant enough? While the authors claim that the difference is statistically significant (n=3), this may end up with experimental artifacts. To say the least, I would urge the authors to try rescue experiments with UGGT1 or 2, to clarify that the defect in UGGT-DKO cells can be reversed. It may also be interesting to see that the subtle difference the authors observed is indeed N-glycan-dependent by testing a non-glycosylated version of the protein (just like NHK-QQQ mutants in Fig. 2C).

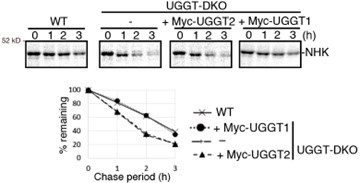

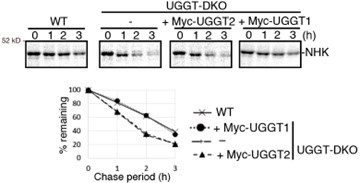

We appreciate this comment. According to this comment, we reevaluated the importance of UGGT2 for ER-protein quality control. As this reviewer mentioned, KO of UGGT2 does not affect the stability of ATF6a, NHK, rRI332-Flag or EMC1-△PQQ-Flag (Fig. 1E, 2A, and 3DE). Furthermore, we tested whether overexpression of UGGT2 reverses the phenotype of UGGT-DKO regarding the degradation rate of NHK, and we found that it did not affect the degradation rate of NHK, whereas overexpression of UGGT1 restored the degradation rate to that in WT cells.

Author response image 1.

Collectively, these facts suggest that the role of UGGT2 in ER protein quality control is rather limited in HCT116 cells. Therefore, we have decided not to mention UGGT2 in the title, and weakened the overall claim that UGGT2 contributes to ER protein quality control. Tissues with high expression of UGGT2 or cultured cells other than HCT116 would be appropriate for revealing the detailed function of UGGT2.

To this reviewer, it is still possible that the involvement of UGGT1 (or 2, if any) could be totally substrate-dependent, and the substrates used in Fig 2D or E happen not to be dependent to the action of UGGTs. To the reviewer, without the data of Fig. 2D and E the authors provide enough evidence to demonstrate the involvement of UGGT1 in preventing premature degradation of glycoprotein ERAD substrates. I am just afraid that the authors may have overinterpreted the data, as if the UGGTs are involved in stabilization of all glycoproteins destined for ERAD.

Based on the point this reviewer mentioned, we decided to delete previous Fig. 2D and 2E. There may be more or less efficacy of UGGT1 for preventing early degradation of substrates.

(3) I am a bit puzzled by the DNJ treatment experiments. First, I do not see the detailed conditions of the DNJ treatment (concentration? Time?). Then, I was a bit surprised to see that there were so little G3M9 glycans formed, and there was about the same amount of G2M9 also formed (Figure 1 Figure supplement 4B-D), despite the fact that glucose trimming of newly syntheized glycoproteins are expected to be completely impaired (unless the authors used DNJ concentration which does not completely impair the trimming of the first Glc). Even considering the involvement of Golgi endo-alpha-mannosidase, a similar amount of G3M9 and G2M9 may suggest that the experimental conditions used for this experiment (i.e. concentration of DNJ, duration of treatment, etc) is not properly optimized.

We think that our experimental condition of DNJ treatment is appropriate to evaluate the effect of DNJ. Referring to the other papers (Ali and Field, 2000; Karlsson et al., 1993; Lomako et al., 2010; Pearse et al., 2010; Tannous et al., 2015), 0.5 mM DNJ is appropriate. In our previously reported experiment, 16 h treatment with kifunensine mannosidase inhibitor was sufficient for N-glycan composition analysis prior to cell collection (Ninagawa et al., 2014), and we treated cells for a similar time in Figure 1-Figure Supplement 4 and 5 (and Figure 1-Figure Supplement 6). We could see the clear effect of DNJ to inhibit degradation of ATF6a with 2 hours of pretreatment (Fig. 1G). Furthermore, our results are very reasonable and consistent with previous findings that DNJ increased GM9 the most (Cheatham et al., 2023; Gross et al., 1983; Gross et al., 1986; Romero et al., 1985). In addition to DNJ, we used CST for further experiments in new figures (Fig. 1H and Figure 1-Figure supplement 6). DNJ and CST are inhibitors of glucosidase; DNJ is a stronger inhibitor of glucosidase II, while CST is a stronger inhibitor of glucosidase I (Asano, 2000; Saunier et al., 1982; Szumilo et al., 1987; Zeng et al., 1997). An increase in G3M9 and G2M9 was detected using CST (Figure1-Figure Supplement 6). Like DNJ, CST also inhibited ATF6a degradation in UGGT-DKO cells (Fig. 1H). These findings show that our experimental condition using glucosidase inhibitor is appropriate and strongly support our model (Fig. 5). Differences between the effects of DNJ and CST are now described in our manuscript pages 8 to 10.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

In this study, Ninagawa et al., shed light on UGGT's role in ER quality control of glycoproteins. By utilizing UGGT1/UGGT2 DKO cells, they demonstrate that several model misfolded glycoproteins undergo early degradation. One such substrate is ATF6alpha where its premature degradation hampers the cell's ability to mount an ER stress response.

While this study convincingly demonstrates early degradation of misfolded glycoproteins in the absence of UGGTs, my major concern is the need for additional experiments to support the "tug of war" model involving UGGTs and EDEMs in influencing the substrate's fate - whether misfolded glycoproteins are pulled into the folding or degradation route. Specifically, it would be valuable to investigate how overexpression of UGGTs and EDEMs in WT cells affects the choice between folding and degradation for misfolded glycoproteins. Considering previous studies indicating that monoglucosylation influences glycoprotein solubility and stability, an essential question is: what is the nature of glycoproteins in UGGTKO/EDEMKO and potentially UGGT/EDEM overexpression cells? Understanding whether these substrates become more soluble/stable when GM9 versus mannose-only translation modification accumulates would provide valuable insights.

In the new figure 2DE, we conducted overexpression experiments of structure formation factors UGGT1 and/or CNX, and degradation factors EDEMs. While overexpression of structure formation factors (Fig. 2DE) and KO of degradation factors (Ninagawa et al., 2015; Ninagawa et al., 2014) increased stability of substrates, KO of UGGT1 (Fig. 1E, 2A and 3DF) and overexpression of degradation factors (Fig. 2DE) (Hirao et al., 2006; Hosokawa et al., 2001; Mast et al., 2005; Olivari et al., 2005) accelerated degradation of substrates. A comparison of the properties of N-glycan with the normal type and the type without glucoses was already reported (Tannous et al., 2015). The rate of degradation of substrate was unchanged, but efficiency of secretion of substrates was affected.

The study delves into the physiological role of UGGT, but is limited in scope, focusing solely on the effect of ATF6alpha in UGGT KO cells' stress response. It is crucial for the authors to investigate the broader impact of UGGT KO, including the assessment of basal ER proteotoxicity levels, examination of the general efflux of glycoproteins from ER, and the exploration of the physiological consequences due to UGGT KO. This broader perspective would be valuable for the wider audience. Additionally, the marked increase in ATF4 activity in UGGTKO requires discussion, which the authors currently omit.

We evaluated the sensitivity of WT and UGGT1-KO cells to ER stress (Figure 4G). KO of UGGT1 increased the sensitivity to ER stress inducer Tg, indicating the importance of UGGT1 for resisting ER stress.

We add the following description in the manuscript about ATF4 activity in UGGT1-KO: “In addition to this, UGGT1 is necessary for proper functioning of ER resident proteins such as ATF6a (Fig. 4B-F). It is highly possible that ATF6a undergoes structural maintenance by UGGT1, which could be necessary to avoid degradation and maintain proper function, because ATF6a with more rigid in structure tended to remain in UGGT1-KO cells (Fig. 4C). Responses of ERSE and UPRE to ER stress, which require ATF6a, were decreased in UGGT1-KO cells (Fig. 4DE). In contrast, ATF4 reporter activity was increased in UGGT1-KO cells (Fig. 4F), while the basal level of ATF4 in UGGT1-KO cells was comparable with that in WT (Figure 1-Figure supplement 2B). The ATF4 pathway might partially compensate the function of the ERSE and UPRE pathways in UGGT1-KO cells in acute ER stress. This is now described on Page 17 in our manuscript.

The discussion section is brief and could benefit from being a separate section. It is advisable for the authors to explore and suggest other model systems or disease contexts to test UGGT's role in the future. This expansion would help the broader scientific community appreciate the potential applications and implications of this work beyond its current scope.

Thank you for making this point. The DISCUSSION part has now been separated in our manuscript. We added some points in the manuscript about other model organisms and diseases in the DISCUSSION as follows: “ Our work focusing on the function of mammalian UGGT1 greatly advances the understanding how ER homeostasis is maintained in higher animals. Considering that Saccharomyces cerevisiae does not have a functional orthologue of UGGT1 (Ninagawa et al., 2020a) and that KO of UGGT1 causes embryonic lethality in mice (Molinari et al., 2005), it would be interesting to know at what point the function of UGGT1 became evolutionarily necessary for life. Related to its importance in animals, it would also be of interest to know what kind of diseases UGGT1 is associated with. Recently, it has been reported that UGGT1 is involved in ER retention of Trop-2 mutant proteins, which are encoded by a causative gene of gelatinous drop-like corneal dystrophy (Tax et al., 2024). Not only this, but since the ER is known to be involved in over 60 diseases (Guerriero and Brodsky, 2012), we must investigate how UGGT1 and other ER molecules are involved in diseases.”

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

This manuscript focuses on defining the importance of UGGT1/2 in the process of protein degradation within the ER. The authors prepared cells lacking UGGT1, UGGT2, or both UGGT1/UGGT2 (DKO) HCT116 cells and then monitored the degradation of specific ERAD substrates. Initially, they focused on the ER stress sensor ATF6 and showed that loss of UGGT1 increased the degradation of this protein. This degradation was stabilized by deletion of ERAD-specific factors (e.g., SEL1L, EDEM) or treatment with mannose inhibitors such as kifunesine, indicating that this is mediated through a process involving increased mannose trimming of the ATF6 N-glycan. This increased degradation of ATF6 impaired the function of this ER stress sensor, as expected, reducing the activation of downstream reporters of ER stress-induced ATF6 activation. The authors extended this analysis to monitor the degradation of other well-established ERAD substrates including A1AT-NHK and CD3d, demonstrating similar increases in the degradation of destabilized, misfolding protein substrates in cells deficient in UGGT. Importantly, they did experiments to suggest that re-overexpression of wild-type, but not catalytically deficient, UGGT rescues the increased degradation observed in UGGT1 knockout cells. Further, they demonstrated the dependence of this sensitivity to UGGT depletion on N-glycans using ERAD substrates that lack any glycans. Ultimately, these results suggest a model whereby depletion of UGGT (especially UGGT1 which is the most expressed in these cells) increases degradation of ERAD substrates through a mechanism involving impaired re-glucosylation and subsequent re-entry into the calnexin/calreticulin folding pathway.

I must say that I was under the impression that the main conclusions of this paper (i.e., UGGT1 functions to slow the degradation of ERAD substrates by allowing re-entry into the lectin folding pathway) were well-established in the literature. However, I was not able to find papers explicitly demonstrating this point. Because of this, I do think that this manuscript is valuable, as it supports a previously assumed assertion of the role of UGGT in ER quality control. However, there are a number of issues in the manuscript that should be addressed.

Notably, the focus on well-established, trafficking-deficient ERAD substrates, while a traditional approach to studying these types of processes, limits our understanding of global ER quality control of proteins that are trafficked to downstream secretory environments where proteins can be degraded through multiple mechanisms. For example, in Figure 1-Figure Supplement 2, UGGT1/2 knockout does not seem to increase the degradation of secretion-competent proteins such as A1AT or EPO, instead appearing to stabilize these proteins against degradation. They do show reductions in secretion, but it isn't clear exactly how UGGT loss is impacting ER Quality Control of these more relevant types of ER-targeted secretory proteins.

We appreciate your comment. It is certainly difficult to assess in detail how UGGT1 functions against secretion-competent proteins, but we think that the folding state of these proteins is improved, which avoids their degradation and increases their secretion. In Figure 1-Figure supplement 2E, there is a clear decrease in secretion of EPO in UGGT1-KO cells, suggesting that UGGT1 also inhibits degradation of such substrates. Note that, as shown in Fig. 3A-C, once a protein forms a solid structure, it is rarely degraded in the ER.

Lastly, I don't understand the link between UGGT, ATF6 degradation, and ATF6 activation. I understand that the idea is that increased ATF6 degradation afforded by UGGT depletion will impair activation of this ER stress sensor, but if that is the case, how does UGGT2 depletion, which only minimally impacts ATF6 degradation (Fig. 1), impact activation to levels similar to the UGGT1 knockout (Fig 4)? This suggests UGGT1/2 may serve different functions beyond just regulating the degradation of this ER stress sensor. Also, the authors should quantify the impaired ATF6 processing shown in Fig 4B-D across multiple replicates.

According to this valuable comment, we reevaluated our manuscript. As this reviewer mentioned, involvement of UGGT2 in the activation of ATF6a cannot be explained only by the folding state of ATF6a. Thus, the part about whether UGGT2 is effective in activating ATF6 is outside the scope of this paper. The main focus of this paper is the contribution of UGGT1 to the ER protein quality control mechanism.

Ultimately, I do think the data support a role for UGGT (especially UGGT1) in regulating the degradation of ERAD substrates, which provides experimental support for a role long-predicted in the field. However, there are a number of ways this manuscript could be strengthened to further support this role, some of which can be done with data they have in hand (e.g., the stats) or additional new experiments.

In this revision period, to further elucidate the function of UGGT, we did several additional experiments (new figures Fig. 1H, 2DE, 4G and, Figure 1-Figure Supplement 6). We hope that these will bring our papers up to the level you have requested.

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations For The Authors):

Minor points:

(1) Abbreviations: GlcNAc, N-acetylglucosamines -> why plural?

Corrected.

(2) Abstract: to this reviewer, it may not be so common to cite references in the abstract.

We submit this manuscript to eLife as “Research Advances”. In the instructions of eLife for “Research Advances”, there is the description: “A reference to the original eLife article should be included in the abstract, e.g. in the format “Previously we showed that XXXX (author, year). Here we show that YYYY.” We follow this.

(3) Introduction: "as the site of biosynthesis of approximately one-third of all proteins." Probably this statement needs a citation?

We added the reference there. You can also confirm this in “The Human Protein Atlas” website. https://www.proteinatlas.org/humanproteome/tissue/secretome

(4) Figure 1F - the authors claimed that maturation of HA was delayed also in UGGT2 cells, but it was not at all clear to me. Rescue experiments with UGGT2 would be desired.

We agree with this reviewer, but there was a statistically significant difference in the 80 min UGGT2-KO strain. Previously, it was reported that HA maturation rate was not affected by UGGT2 (Hung et al., 2022). We think that the difference is not large. A rescue experiment of UGGT2 on the degradation of NHK was conducted, and is shown in this response to referees.

(5) Figure 4A, here also the authors claim that UGGT2 is "slightly" involved in folding of ATF6alpha(P) but it is far from convincing to this reviewer.

Now we also think that involvement of UGGT2 in ER protein quality control should be examined in the future.

(6) Page 11, line 7 from the bottom: "peak of activation was shifted from 1 hour to 4 hours after the treatment of Tg in UGGT-KO cells". I found this statement a bit awkward; how can the authors be sure that "the peak" is 4 hours when the longest timing tested is 4 hours (i.e. peak may be even later)?

Corrected. We deleted the description.

(7) Page 11, line 4 "a more rigid structure that averts degradation" Can the authors speculate what this "rigid" structure actually means? The reviewer has to wonder what kind of change can occur to this protein with or without UGGT1. Binding proteins? The difference in susceptibility against trypsin appears very subtle anyway (Figure 4 Figure Supplement 1).

Let us add our thoughts here: Poorly structured ATF6a is immediately routed for degradation in UGGT1-KO cells. As a result, ATF6a with a stable or rigid structure have remained in the UGGT1-KO strain. ATF6a with a metastable state is tended to be degraded without assistance of UGGT1.

(8) Figure 1 Figure supplement 2; based on the information provided, I calculate the relative ratio of UGGT2/UGGT1 in HCT116 which is 4.5%, and in HeLa 26%. Am I missing something? Also significant figure, at best, should be 2, not 3 (i.e. 30%, not 29.8%).

Corrected. Thank you for this comment.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations For The Authors):

(1) The effect in Fig. 2B with UGGT1-D1358A add-back is minimal. Testing the inactive and active add-back on other substrates, such as ATF6alpha, which undergoes a more rapid degradation, would provide a more comprehensive assessment.

To examine the effect of full length and inactive mutant of UGGT1 in UGGT1-KO and UGGT2-KO on the rate of degradation of endogenous ATF6a, we tried to select more than 300 colonies stably expressing full-length Myc-UGGT1/2, UGGT1/2-Flag, and UGGT1/2 (no tag), and their point mutant of them. However, no cell lines expressing nearly as much or more UGGT1/2 than endogenous ones were obtained. The expression level of UGGT1 seemed to be tightly regulated. A low-expressing stable cell line could not recover the phenotype of ATF6a degradation.

We also tried to measure the degradation rate of exogenously expressed ATF6a. But overexpressed ATF6a is partially transported to the Golgi and cleaved by proteases, which makes it difficult to evaluate only the effect of degradation.

(2) In reference to this statement on pg. 11:

"This can be explained by the rigid structure of ATF6(P) lacking structural flexibility to respond to ER stress because the remaining ATF6(P) in UGGT1-KO cells tends to have a more rigid structure that averts degradation, which is supported by its slightly weaker sensitivity to trypsin (Figure 4-figure supplement 1A). "

The rationale for testing ATF6(P) rigidity via trypsin digestion needs clarification. The authors should provide more background, especially if it relates to previous studies demonstrating UGGT's influence on substrate solubility. If trypsin digestion is indeed addressing this, it should be applied consistently to all tested misfolded glycoproteins, ensuring a comprehensive approach.

We now provide more background with three references about trypsin digestion. Trypsin digestion allows us to evaluate the structure of proteins originated from the same gene, but it can sometimes be difficult to comparatively evaluate the structure of proteins originated from different genes. For example, antitrypsin is resistant to trypsin by its nature, which does not necessarily mean that antitrypsin forms a more stable structure than other proteins. NHK, a truncated version of antitrypsin, is still resistant to trypsin compared with other substrates.

(3) Many of the figures described in the manuscript weren't referred to a specific panel. For example, pg. 12 "Fig. 1E and Fig.5," the exact panel for Fig. 5 wasn't referenced.

Thank you for this comment. Corrected.

(4) For experiments measuring the composition of glycoproteins in different KO lines, it is necessary to do the experiment more than once for conducting statistical analysis and comparisons. Moreover, the authors did not include raw composition data for these experiments. Statistical analysis should also be done for Fig. 4E-F.

Our N-glycan composition data (Figure 1-Figure supplement 5 and 6C) is consistent with previous our papers (George et al., 2021; George et al., 2020; Ninagawa et al., 2015; Ninagawa et al., 2014). We did it twice in the previous study and please refer to it regarding statistical analysis (George et al., 2020). We add the raw composition data of N-glycan (Figure 1-Figure supplement 4 and 6B). In Fig. 4D-F, now statistical analysis is included.

Ali, B.R., and M.C. Field. 2000. Glycopeptide export from mammalian microsomes is independent of calcium and is distinct from oligosaccharide export. Glycobiology. 10:383-391.

Asano, N. 2000. Glycosidase-Inhibiting Glycomimetic Alkaloids. Biological Activities and Therapeutic Perspectives. Journal of Synthetic Organic Chemistry, Japan. 58:666-675.

Cheatham, A.M., N.R. Sharma, and P. Satpute-Krishnan. 2023. Competition for calnexin binding regulates secretion and turnover of misfolded GPI-anchored proteins. J Cell Biol. 222.

George, G., S. Ninagawa, H. Yagi, J.I. Furukawa, N. Hashii, A. Ishii-Watabe, Y. Deng, K. Matsushita, T. Ishikawa, Y.P. Mamahit, Y. Maki, Y. Kajihara, K. Kato, T. Okada, and K. Mori. 2021. Purified EDEM3 or EDEM1 alone produces determinant oligosaccharide structures from M8B in mammalian glycoprotein ERAD. Elife. 10.

George, G., S. Ninagawa, H. Yagi, T. Saito, T. Ishikawa, T. Sakuma, T. Yamamoto, K. Imami, Y. Ishihama, K. Kato, T. Okada, and K. Mori. 2020. EDEM2 stably disulfide-bonded to TXNDC11 catalyzes the first mannose trimming step in mammalian glycoprotein ERAD. Elife. 9:e53455.

Gross, V., T. Andus, T.A. Tran-Thi, R.T. Schwarz, K. Decker, and P.C. Heinrich. 1983. 1-deoxynojirimycin impairs oligosaccharide processing of alpha 1-proteinase inhibitor and inhibits its secretion in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 258:12203-12209.

Gross, V., T.A. Tran-Thi, R.T. Schwarz, A.D. Elbein, K. Decker, and P.C. Heinrich. 1986. Different effects of the glucosidase inhibitors 1-deoxynojirimycin, N-methyl-1-deoxynojirimycin and castanospermine on the glycosylation of rat alpha 1-proteinase inhibitor and alpha 1-acid glycoprotein. Biochem J. 236:853-860.

Hirao, K., Y. Natsuka, T. Tamura, I. Wada, D. Morito, S. Natsuka, P. Romero, B. Sleno, L.O. Tremblay, A. Herscovics, K. Nagata, and N. Hosokawa. 2006. EDEM3, a soluble EDEM homolog, enhances glycoprotein endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation and mannose trimming. J Biol Chem. 281:9650-9658.

Hosokawa, N., I. Wada, K. Hasegawa, T. Yorihuzi, L.O. Tremblay, A. Herscovics, and K. Nagata. 2001. A novel ER alpha-mannosidase-like protein accelerates ER-associated degradation. EMBO reports. 2:415-422.

Hung, H.H., Y. Nagatsuka, T. Solda, V.K. Kodali, K. Iwabuchi, H. Kamiguchi, K. Kano, I. Matsuo, K. Ikeda, R.J. Kaufman, M. Molinari, P. Greimel, and Y. Hirabayashi. 2022. Selective involvement of UGGT variant: UGGT2 in protecting mouse embryonic fibroblasts from saturated lipid-induced ER stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 119:e2214957119.

Karlsson, G.B., T.D. Butters, R.A. Dwek, and F.M. Platt. 1993. Effects of the imino sugar N-butyldeoxynojirimycin on the N-glycosylation of recombinant gp120. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 268:570-576.

Lomako, J., W.M. Lomako, C.A. Carothers Carraway, and K.L. Carraway. 2010. Regulation of the membrane mucin Muc4 in corneal epithelial cells by proteosomal degradation and TGF-beta. Journal of cellular physiology. 223:209-214.

Mast, S.W., K. Diekman, K. Karaveg, A. Davis, R.N. Sifers, and K.W. Moremen. 2005. Human EDEM2, a novel homolog of family 47 glycosidases, is involved in ER-associated degradation of glycoproteins. Glycobiology. 15:421-436.

Ninagawa, S., T. Okada, Y. Sumitomo, S. Horimoto, T. Sugimoto, T. Ishikawa, S. Takeda, T. Yamamoto, T. Suzuki, Y. Kamiya, K. Kato, and K. Mori. 2015. Forcible destruction of severely misfolded mammalian glycoproteins by the non-glycoprotein ERAD pathway. J Cell Biol. 211:775-784.

Ninagawa, S., T. Okada, Y. Sumitomo, Y. Kamiya, K. Kato, S. Horimoto, T. Ishikawa, S. Takeda, T. Sakuma, T. Yamamoto, and K. Mori. 2014. EDEM2 initiates mammalian glycoprotein ERAD by catalyzing the first mannose trimming step. J Cell Biol. 206:347-356.

Olivari, S., C. Galli, H. Alanen, L. Ruddock, and M. Molinari. 2005. A novel stress-induced EDEM variant regulating endoplasmic reticulum-associated glycoprotein degradation. J Biol Chem. 280:2424-2428.

Pearse, B.R., T. Tamura, J.C. Sunryd, G.A. Grabowski, R.J. Kaufman, and D.N. Hebert. 2010. The role of UDP-Glc:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase 1 in the maturation of an obligate substrate prosaposin. J Cell Biol. 189:829-841.

Romero, P.A., B. Saunier, and A. Herscovics. 1985. Comparison between 1-deoxynojirimycin and N-methyl-1-deoxynojirimycin as inhibitors of oligosaccharide processing in intestinal epithelial cells. Biochem J. 226:733-740.

Saunier, B., R.D. Kilker, J.S. Tkacz, A. Quaroni, and A. Herscovics. 1982. Inhibition of N-linked complex oligosaccharide formation by 1-deoxynojirimycin, an inhibitor of processing glucosidases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 257:14155-14161.

Szumilo, T., G.P. Kaushal, and A.D. Elbein. 1987. Purification and properties of the glycoprotein processing N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase II from plants. Biochemistry. 26:5498-5505.

Tannous, A., N. Patel, T. Tamura, and D.N. Hebert. 2015. Reglucosylation by UDP-glucose:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase 1 delays glycoprotein secretion but not degradation. Molecular biology of the cell. 26:390-405.

Zeng, Y., Y.T. Pan, N. Asano, R.J. Nash, and A.D. Elbein. 1997. Homonojirimycin and N-methyl-homonojirimycin inhibit N-linked oligosaccharide processing. Glycobiology. 7:297-304.