Peer review process

Not revised: This Reviewed Preprint includes the authors’ original preprint (without revision), an eLife assessment, public reviews, and a provisional response from the authors.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorAndrew WestDuke University, Durham, United States of America

- Senior EditorAmy AndreottiIowa State University, Ames, United States of America

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Summary:

The Roco proteins are a family of GTPases characterized by the conserved presence of an ROC-COR tandem domain. How GTP binding alters the structure and activity of Roco proteins remains unclear. In this study, Galicia C et al. took advantage of conformation-specific nanobodies to trap CtRoco, a bacterial Roco, in an active monomeric state and determined its high-resolution structure by cryo-EM. This study, in combination with the previous inactive dimeric CtRoco, revealed the molecular basis of CtRoco activation through GTP-binding and dimer-to-monomer transition.

Strengths:

The reviewer is impressed by the authors' deep understanding of the CtRoco protein. Capturing Roco proteins in a GTP-bound state is a major breakthrough in the mechanistic understanding of the activation mechanism of Roco proteins and shows similarity with the activation mechanism of LRRK2, a key molecule in Parkinson's disease. Furthermore, the methodology the authors used in this manuscript - using conformation-specific nanobodies to trap the active conformation, which is otherwise flexible and resistant to single-particle average - is highly valuable and inspiring.

Weakness:

Though written with good clarity, the paper will benefit from some clarifications.

1. The angular distribution of particles for the 3D reconstructions should be provided (Figure 1 - Sup. 1 & Sup. 2).

2. The B-factors for protein and ligand of the model, Map sharpening factor, and molprobity score should be provided (Table 1).

3. A supplemental Figure to Figure 2B, illustrating how a0-helix interacts with COR-A&LRR before and after GTP binding in atomic details, will be helpful for the readers to understand the critical role of a0-helix during CtRoco activation.

4. For the following statement, "On the other hand, only relatively small changes are observed in the orientation of the Roc a3 helix. This helix, which was previously suggested to be an important element in the activation of LRRK2 (Kalogeropulou et al., 2022), is located at the interface of the Roc and CORB domains and harbors the residues H554 and Y558, orthologous to the LRRK2 PD mutation sites N1337 and R1441, respectively."

It is not surprising the a3-helix of the ROC domain only has small changes when the ROC domain is aligned (Figure 2E). However, in the study by Zhu et al (DOI: 10.1126/science.adi9926), it was shown that a3-helix has a "see-saw" motion when the COR-B domain is aligned. Is this motion conserved in CtRoco from inactive to active state?

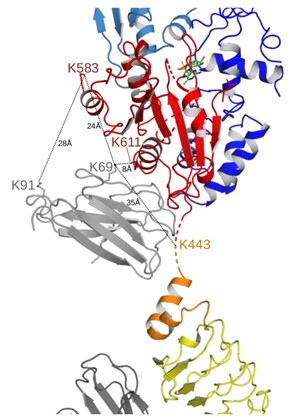

5. A supplemental figure showing the positions of and distances between NbRoco1 K91 and Roc K443, K583, and K611 would help the following statement. "Also multiple crosslinks between the Nbs and CtRoco, as well as between both nanobodies were found. ... NbRoco1-K69 also forms crosslinks with two lysines within the Roc domain (K583 and K611), and NbRoco1-K91 is crosslinked to K583".

6. It would be informative to show the position of CtRoco-L487 in the NF and GTP-bound state and comment on why this mutation favors GTP hydrolysis.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary

The manuscript by Galicia et al describes the structure of the bacterial GTPyS-bound CtRoco protein in the presence of nanobodies. The major relevance of this study is in the fact that the CtRoco protein is a homolog of the human LRRK2 protein with mutations that are associated with Parkinson's disease. The structure and activation mechanisms of these proteins are very complex and not well understood. Especially lacking is a structure of the protein in the GTP-bound state. Previously the authors have shown that two conformational nanobodies can be used to bring/stabilize the protein in a monomer-GTPyS-bound state. In this manuscript, the authors use these nanobodies to obtain the GTPyS-bound structure and importantly discuss their results in the context of the mammalian LRRK2 activation mechanism and mutations leading to Parkinson's disease. The work is well performed and clearly described. In general, the conclusions on the structure are reasonable and well-discussed in the context of the LRRK2 activation mechanism.

Strengths:

The strong points are the innovative use of nanobodies to stabilize the otherwise flexible protein and the new GTPyS-bound structure that helps enormously in understanding the activation cycle of these proteins.

Weakness:

The strong point of the use of nanobodies is also a potential weak point; these nanobodies may have induced some conformational changes in a part of the protein that will not be present in a GTPyS-bound protein in the absence of nanobodies.

Two major points need further attention.

1. Several parts of the protein are very flexible during the monomer-dimer activity cycle. This flexibility is crucial for protein function, but obviously hampers structure resolution. Forced experiments to reduce flexibility may allow better structure resolution, but at the same time may impede the activation cycle. Therefore, careful experiments and interpretation are very critical for this type of work. This especially relates to the influence of the nanobodies on the structure that may not occur during the "normal" monomer-dimer activation cycle in the absence of the nanobodies (see also point 2). So what is the evidence that the nanobody-bound GTPyS-bound state is biochemically a reliable representative of the "normal" GTP-bound state in the absence of nanobodies, and therefore the obtained structure can be confidentially used to interpret the activation mechanism as done in the manuscript.

2. The obtained structure with two nanobodies reveals that the nanobodies NbRoco1 and NbRoco2 bind to parts of the protein by which a dimer is impossible, respectively to a0-helix of the linker between Roc-COR and LRR, and to the cavity of the LRR that in the dimer binds to the dimerizing domain CORB. It is likely the open monomer GTP-bound structure is recognized by the nanobodies in the camelid, suggesting that overall the open monomer structure is a true GTP-bound state. However, it is also likely that the binding energy of the nanobody is used to stabilize the monomer structure. It is not automatically obvious that in the details the obtained nonobody-Roco-GTPyS structure will be identical to the "normal" Roco-GTPyS structure. What is the influence of nanobody-binding on the conformation of the domains where they bind; the binding energy may be used to stabilize a conformation that is not present in the absence of the nanobody. For instance, NbRoco1 binds to the a0 helix of the linker; what is here the "normal" active state of the Roco protein, and is e.g. the angle between RocCOR and LRR also rotated by 135 degrees? Furthermore, nanobody NbRoco2 in the LRR domain is expected to stabilize the LRR domain; it may allow a position of the LRR domain relative to the rest of the protein that is not present without nanobody in the LRR domain. I am convinced that the observed open structure is a correct representation of the active state, but many important details have to be supported by e,g, their CX-MS experiments, and in the end probably need confirmation by more structures of other active Roco proteins or confirmation by a more dynamic sampling of the active states by e.g. molecular dynamics or NMR.