Peer review process

Revised: This Reviewed Preprint has been revised by the authors in response to the previous round of peer review; the eLife assessment and the public reviews have been updated where necessary by the editors and peer reviewers.

Read more about eLife’s peer review process.Editors

- Reviewing EditorPeter KooCold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, United States of America

- Senior EditorQiang CuiBoston University, Boston, United States of America

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors introduce a denoising-style model that incorporates both structure and primary-sequence embeddings to generate richer embeddings of peptides. My understanding is that the authors use ESM for the primary sequence embeddings, take resolved structures (or use structural predictions from AlphaFold when they're not available), then develop an architecture to combine these two with a loss that seems reminiscent of diffusion models or masked language model approaches. The embeddings can be viewed as ensemble-style embedding of the two levels of sequence information, or with AlphaFold, an ensemble of two methods (ESM+AlphaFold). The authors also gather external datasets to evaluate their approach and compare it to previous approaches. The approach seems promising and appears to out-compete previous methods at several tasks. Nonetheless, I have strong concerns about a lack of verbosity as well as exclusion of relevant methods and references.

Advances:

I appreciate the breadth of the analysis and comparisons to other methods. The authors separate tasks, models, and sizes of models in an intuitive, easy-to-read fashion that I find valuable for selecting a method for embedding peptides. Moreover, the authors gather two datasets for evaluating embeddings' utility for predicting thermostability. Overall, the work should be helpful for the field as more groups choose methods/pretraining strategies amenable to their goals, and can do so in an evidence-guided manner.

Considerations:

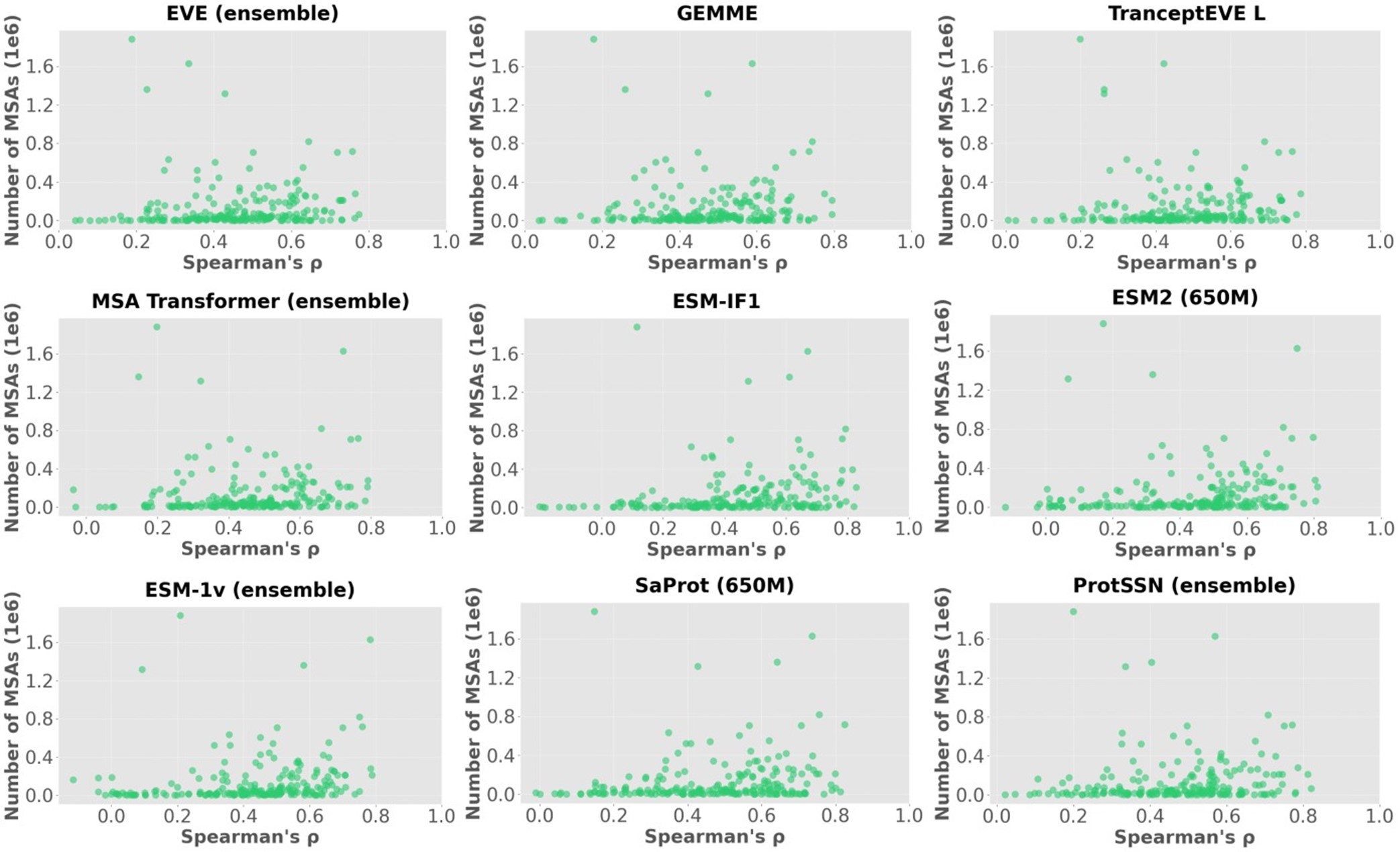

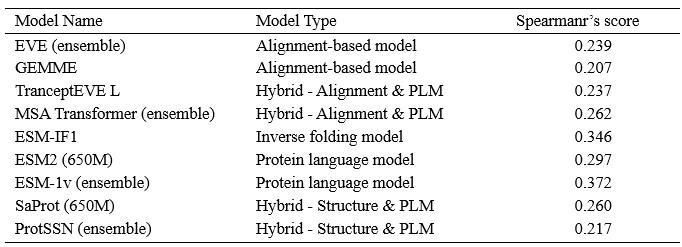

Primarily, a majority of the results and conclusions (e.g., Table 3) are reached using data and methods from ProteinGym, yet the best-performing methods on ProteinGym are excluded from the paper (e.g., EVE-based models and GEMME). In the ProteinGym database, these methods outperform ProtSSN models. Moreover, these models were published over a year---or even 4 years in the case of GEMME---before ProtSSN, and I do not see justification for their exclusion in the text.

Secondly, related to comparison of other models, there is no section in the methods about how other models were used, or how their scores were computed. When comparing these models, I think it's crucial that there are explicit derivations or explanations for the exact task used for scoring each method. In other words, if the pre-training is indeed the important advance of the paper, the paper needs to show this more explicitly by explaining exactly which components of the model (and previous models) are used for evaluation. Are the authors extracting the final hidden layer representations of the model, treating these as features, then using these features in a regression task to predict fitness/thermostability/DDG etc.? How are the model embeddings of other methods being used, since, for example, many of these methods output a k-dimensional embedding of a given sequence, rather than one single score that can be correlated with some fitness/functional metric. Summarily, I think the text is lacking an explicit mention of how these embeddings are being summarized or used, as well as how this compares to the model presented.

I think the above issues can mainly be addressed by considering and incorporating points from Li et al. 2024[1] and potentially Tang & Koo 2024[2]. Li et al.[1] make extremely explicit the use of pretraining for downstream prediction tasks. Moreover, they benchmark pretraining strategies explicitly on thermostability (one of the main considerations in the submitted manuscript), yet there is no mention of this work nor the dataset used (FLIP (Dallago et al., 2021)) in this current work. I think a reference and discussion of [1] is critical, and I would also like to see comparisons in line with [1], as [1] is very clear about what features from pretraining are used, and how. If the comparisons with previous methods were done in this fashion, this level of detail needs to be included in the text.

To conclude, I think the manuscript would benefit substantially from a more thorough comparison of previous methods. Maybe one way of doing this is following [1] or [2], and using the final embeddings of each method for a variety of regression tasks---to really make clear where these methods are performing relative to one another. I think a more thorough methods section detailing how previous methods did their scoring is also important. Lastly, TranceptEVE (or a model comparable to it) and GEMME should also be mentioned in these results, or at the bare minimum, be given justification for their absence.

[1] Feature Reuse and Scaling: Understanding Transfer Learning with Protein Language Models, Francesca-Zhoufan Li, Ava P. Amini, Yisong Yue, Kevin K. Yang, Alex X. Lu bioRxiv 2024.02.05.578959; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.05.578959

[2] Evaluating the representational power of pre-trained DNA language models for regulatory genomics, Ziqi Tang, Peter K Koo bioRxiv 2024.02.29.582810; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.29.582810

Comments on revisions:

My concerns have been addressed. What seems to remain are some semantical disagreements and I'm not sure that these will be answered here. Do MSAs and other embedding methods lead to some notable type of data leakage? Does this leakage qualify as "x-shot" learning under current definitions?

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

To design proteins and predict disease, we want to predict the effects of mutations on the function of a protein. To make these predictions, biologists have long turned to statistical models that learn patterns that are conserved across evolution. There is potential to improve our predictions however by incorporating structure. In this paper the authors build a denoising auto-encoder model that incorporates sequence and structure to predict mutation effects. The model is trained to predict the sequence of a protein given its perturbed sequence and structure. The authors demonstrate that this model is able to predict the effects of mutations better than sequence-only models.

As well, the authors curate a set of assays measuring the effect of mutations on thermostability. They demonstrate their model also predicts the effects of these mutations better than previous models and make this benchmark available for the community.

Strengths:

The authors describe a method that makes accurate mutation effect predictions by informing its predictions with structure.

The authors curate a new dataset of assays measuring thermostability. These can be used to validate and interpret mutation effect prediction methods in the future.

Weaknesses:

In the review period, the authors included a previous method, SaProt, that similarly uses protein structure to predict the effects of mutations, in their evaluations. They see that SaProt performs similarly to their method.

ProteinGym is largely made of deep mutational scans, which measure the effect of every mutation on a protein. These new benchmarks contain on average measurements of less than a percent of all possible point mutations of their respective proteins. It is unclear what sorts of protein regions these mutations are more likely to lie in; therefore it is challenging to make conclusions about what a model has necessarily learned based on its score on this benchmark. For example, several assays in this new benchmark seem to be similar to each other, such as four assays on ubiquitin performed in pH 2.25 to pH 3.0.

Comments on revisions:

I think the rounds of review have improved the paper and I've raised my score.